Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahmed H Abdelhafiz | -- | 2280 | 2022-07-04 10:21:53 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2280 | 2022-07-04 10:37:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Abdelhafiz, A.; Bisht, S.; Kovacevic, I.; Pennells, D.; Sinclair, A. Insulin—Low Threshold of Therapy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24788 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Abdelhafiz A, Bisht S, Kovacevic I, Pennells D, Sinclair A. Insulin—Low Threshold of Therapy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24788. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Abdelhafiz, Ahmed, Shail Bisht, Iva Kovacevic, Daniel Pennells, Alan Sinclair. "Insulin—Low Threshold of Therapy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24788 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Abdelhafiz, A., Bisht, S., Kovacevic, I., Pennells, D., & Sinclair, A. (2022, July 04). Insulin—Low Threshold of Therapy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24788

Abdelhafiz, Ahmed, et al. "Insulin—Low Threshold of Therapy." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 July, 2022.

Copy Citation

The global prevalence of comorbid diabetes and frailty is increasing due to increasing life expectancy. Frailty appears to be a metabolically heterogeneous condition that may affect the clinical decision making on the most appropriate glycaemic target and the choice of the most suitable hypoglycaemic agent for each individual. The metabolic profile of frailty appears to span across a spectrum that starts at an anorexic malnourished (AM) frail phenotype on one end and a sarcopenic obese (SO) phenotype on the other.

older people

diabetes mellitus

1. Introduction

The global prevalence of diabetes is increasing, particularly, in the older age groups. For example, 44% of people with diabetes are above the age of 65 years [1]. Frailty is an emerging new complication of diabetes and increasingly recognised in clinical guidelines for diabetes management [2][3][4][5][6]. Frailty is not a homogeneous concept and appears to have a spectrum of different metabolic phenotypes, which may influence the choice of the most suitable hypoglycaemic agents for an individual [6]. The metabolic spectrum of frailty starts by the anorexic malnourished (AM) phenotype with significant weight loss and less insulin resistance on one end, and the sarcopenic obese (SO) phenotype with excess weight and increased insulin resistance on the other end [6].

2. Insulin Analogues Safety

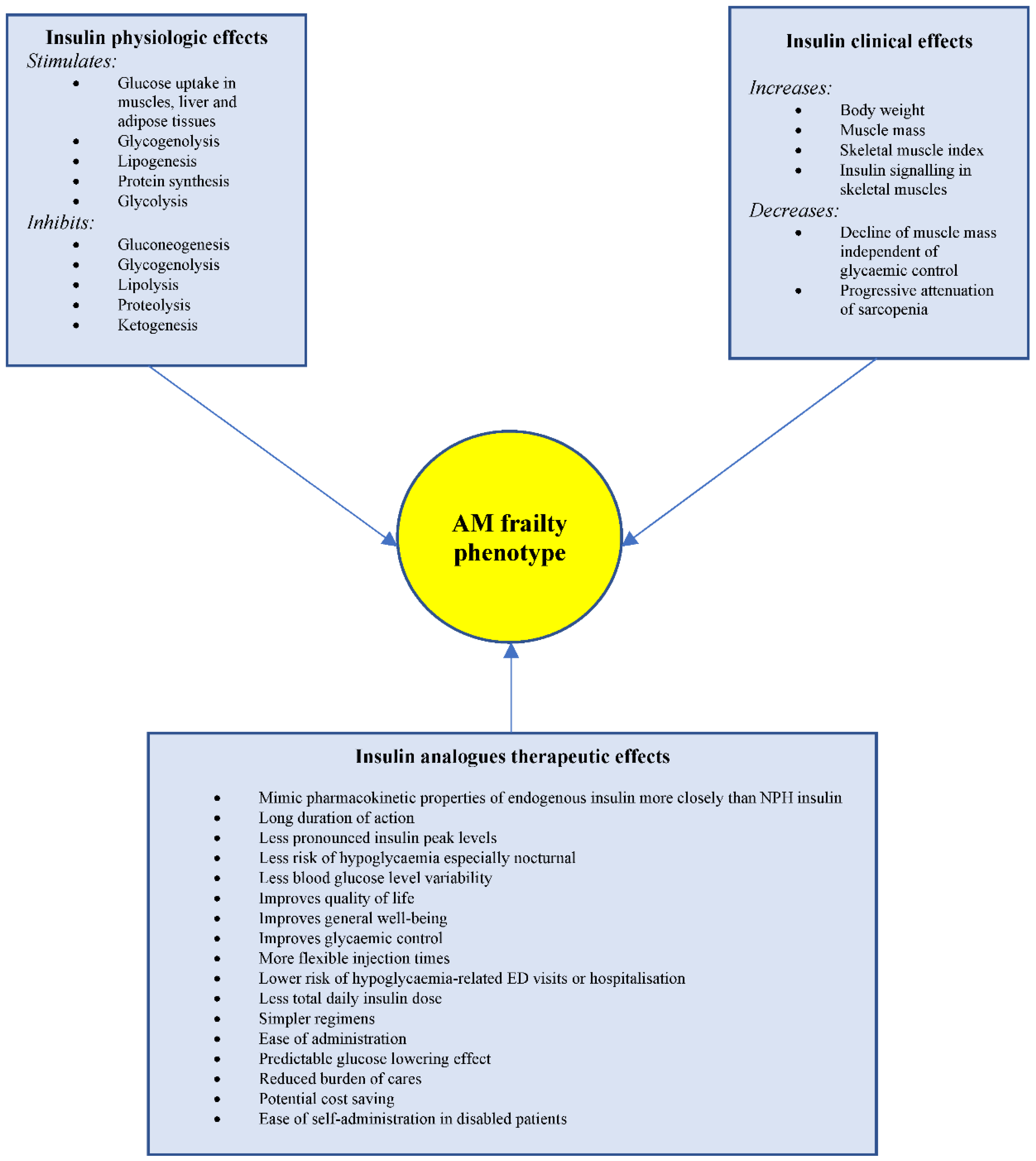

Insulin analogues, such as insulin glargine, detemir and degludec, are structurally altered human insulins that mimic the pharmacokinetic properties of endogenous insulin more closely than intermediate-acting insulins. Because of the long duration of action and the less pronounced insulin peak, long-acting insulin analogues have less risk of hypoglycaemia especially nocturnal hypoglycaemia. The evidence of this benefit was conflicting in earlier clinical trials [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14]. However, most of these earlier studies predominantly included patients under the age of 60 years, which caused it to be less powered in detecting the efficacy and safety of long-acting insulin analogues in older age groups who are at increased risk of hypoglycaemia and its severe consequences than younger people. Through researchers literature search and following the application of the exclusion criteria, five studies investigated the safety of long-acting insulin analogues in older people with diabetes and were included in this manuscript. The recent studies that included older people with type 2 diabetes have shown some benefits of the new long-acting insulin analogues, compared to the older human insulins (Table 1). Fujimoto et al. showed that twice-daily insulin degludec/insulin aspart to improve daily glucose level variability, morning and evening glucose control and quality of life (QOL) in 22 Japanese men, with a mean (SD) age of 68.0 (9.9) years, previously treated with premixed insulin [15]. However, there was no significant difference in the incidence of hypoglycaemia before and after insulin switching. The total and therapy-related QOL feeling scores favoured insulin degludec/insulin aspart; whereas social, physical and daily activities scores were not significantly different. The flexibility of injection timing and glycaemic control may explain the improvement in the total and therapy-related feeling subscores in the QOL questionnaire. However, this research was limited by the small sample size and the short duration of follow-up, which may suggest that the switch in the insulin regimen might not explain all the changes in the endpoints, and other factors, such as lifestyle changes and physicians’ motivations, might have contributed to the results. Another limitation was that the incidence in hypoglycaemia may have not been accurate, because the frequency of this event was calculated based on self-measured blood glucose levels or patients’ symptoms. Lipska et al., in their large retrospective observational study of 22,489 patients with type 2 diabetes, found that the initiation of a basal insulin analogue (glargine or detemir) was not associated with a reduced risk of hypoglycaemia-related emergency department (ED) visits or hospital admissions compared with NPH insulin. Glycaemic control was similar in both groups after one year of follow-up [16]. However, the population included in this entry were relatively young, with a mean (SD) age of 60.2 (11.8) years. Previous studies using the national registries in Finland that included participants of similar ages to those presented in Lipska et al.’s study showed a significantly increased risk of hospitalisation related to severe hypoglycaemia with the use of NPH insulin compared with insulin detemir or glargine [17][18]. In addition, although Lipska et al.’s was a large study, only 1928 participants of the total 25,489 used insulin analogues, and despite matching on the propensity score quintiles, some differences between the two groups remained, suggesting that the study did not fully adjust for the confounding factors. Recently, Bradley et al. showed that the initiation of long-acting insulin analogues was associated with a lower risk of ED visits or hospitalisations for hypoglycaemia compared with NPH insulin in older patients (≥65 years) with type 2 diabetes in Medicare beneficiaries [19]. The strength of this research was the large sample size of 575,008 patients with type 2 diabetes, of an older age, with a mean (SD) of 74.9 (6.7) years, and the fact that a large proportion of patients were treated with insulin glargine (407,018 patients) or insulin detemir (141,588 patients). The hazard ratio (HR) for hypoglycaemia was 0.71, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.63 to 0.80 for glargine vs. NPH insulin, and 0.72, 0.63 to 0.82 for detemir vs. NPH insulin. The older ages of the participants in this research compared to the study conducted by Lipska et al., suggest that age may have contributed to the disparity between the two studies [16]. In the post hoc analysis, Bradley et al. observed that in participants aged 65–68 years; the use of glargine or detemir was not associated with ED visits or hospitalisations for hypoglycaemia compared with NPH insulin [19]. However, in older participants (69–87 years of age), the use of long-acting analogues was associated with a reduced risk of hypoglycaemia compared with NPH insulin. Betônico et al. demonstrated better glycaemic control and fewer nocturnal hypoglycaemia in 34 patients, mean (SD) age 63.0 (7.0) years, using insulin glargine compared with 16 patients, with a mean (SD) age of 60.0 (8.7) years, using NPH insulin [20]. The importance of this research was that it included patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 3 and 4, which is more common in older people. CKD is associated with a slower insulin degradation, increasing its duration of action that might increase the risk of hypoglycaemia [21]. However, because the insulin analogue has no peak action, it showed less risk of hypoglycaemia in this population. This is clinically relevant as, with the progression of CKD, most hypoglycaemic medications need dose reductions, and the adjustment of these medications, in the face of renal impairment, may not be enough to keep diabetes under control, and therefore insulin is the most effective therapy in this situation [22]. Özçelik et al. showed that the switch from premixed and intensive insulin to twice daily degludec/aspart insulin was associated with a significant reduction in the daily insulin dose requirement and the incidence of hypoglycaemia [23]. The use of premixed and intensive insulin is a complex regimen and may not be an easy option for daily life in older people with diabetes; therefore, the switch to degludec/aspart insulin may be a less complex regimen, as demonstrated in this research and previous studies [24]. Figure 1 illustrates the advantage of the physiological, clinical and therapeutic properties of insulin in the AM frail phenotype.

Figure 1. Advantage of the physiologic, clinical and therapeutic effects of insulin in the AM frailty phenotype. AM = Anorexic malnourished, ED = Emergency department.

Table 1. Recent studies exploring efficacy and safety of insulin analogues compared with human insulin.

| Study | Patients | Aim to | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fujimoto K. et al., prospective, observational, Japan, 2018 [15]. | 22 patients with type 2 DM, mean (SD) age 68.0 (9.9) Y, treated with premixed insulin for 2 M, then IDegAsp for next 2 M. |

Investigate changes in glucose variability and QOL during switch from premixed insulin to IDegAsp twice daily. | Switching to IDegAsp from premixed insulin: A. Improved daily glucose level variability, morning and evening glucose control and QOL. B. No change in day-to-day variability of morning fasting glucose levels. |

| Lipska KJ et al., retrospective observational, US, 2018 [16]. | 25,489 patients with type 2 DM initiated basal or NPH insulin, mean (SD) age 60.2 (11.8) Y. F/Up 1.7Y. | Compare rates of hypoglycaemia-related ED visits or hospitalisation associated with initiation of long-acting insulin analogues vs. NPH insulin. | A. In 1928 patients initiated on insulin analogue, there were 39 hypoglycaemia-related ED visits or hospital admissions (11.9 events, 95% CI 8.1 to 15.6/1000 person–years) compared with 354 events among 23,561 patients on NPH (8.8 events, 7.9 to 9.8/1000 person–years, p = 0.07). B. Adjusted HR 1.16, 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.78 for hypoglycaemia-related events with insulin analogue use. C. After one year, there was no significant difference in glycaemic control between both groups. |

| Bradley MC et al., retrospective, US, 2021 [19]. | Medicare 575, 008 patients, mean (SD) age 74.9 (6.7) Y with type 2 DM, 407,018 initiated insulin glargine, 141,588 detemir, 26,402 NPH. | Examine risk of ED visits or hospitalisations due to hypoglycaemia in older community patients with type 2 DM who initiated long acting or NPH insulin. | A. Incidence rates for ED visits or hospitalisations for hypoglycaemia per 1000 person–years were 17.37 (95% CI 16.89 to17.84) for glargine and 26.64 (95% CI 26.01–27.3) for NPH. B. For detemir and NPH, incidence rates were 16.69 (15.92 to 17.51) and 25.04 (24.01 to 26.11), respectively. C. Glargine or detemir use associated with reduced risk of hypoglycaemia compared with NPH (HR for glargine vs. NPH 0.71, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.80, and detemir vs. NPH insulin 0.72, 0.63 to 0.82). |

| Betônico CC et al., prospective, randomized, 2-way, crossover, open-label, Brazil, 2019 [20]. | 34 patients with type 2 DM randomly assigned to glargine U100 {16 patients, mean (SD) age 63.0 (7.0) Y} or NPH {18 patients, mean (SD) age 60.0 (8.7) Y}. | Compare glycaemic response to glargine U100 or NPH in patients with type 2 DM and CKD stages 3 and 4. | A. After 24 weeks, mean HbA1c declined from 8.86% (72.7 mmol/mol) to 7.95% (62.8 mmol/mol) in glargine group, but increased from 8.21% (66.2 mmol/mol) to 8.44% (69.4 mmol/mol) in INPH group, p = 0.029. B. Incidence of nocturnal hypoglycaemia was 3 times lower with glargine (0.5 events/patient) than with INPH (1.5 events/patient; p = 0.047). |

| Ozcelik et al., prospective observational, Turkey, 2021 [22]. | 115 patients with type 2 DM, group 1, 55 on premixed insulin switched to IDegAsp; group 2, 60 on intensive insulin switched to bd IDegAsp, median (IQR) age 67.0 (62.0–69.0). Y. | Evaluate efficacy and safety of transition from premixed and intensive insulin to twice-daily insulin IDegAsp. | A. Mean (SD) rate hypoglycaemia 1.5 (0.85)/week before treatment switch in group 1 decreased to 0.03 (0.11)/week after IdegAsp (p < 0.0001). B. In group 2, episodes of hypoglycaemia were 0.93 (1.17)/week before treatment transition, decreased to 0.07 (0.25)/week after IDegAsp (p < 0.0001). |

3. Insulin—Low Threshold of Therapy

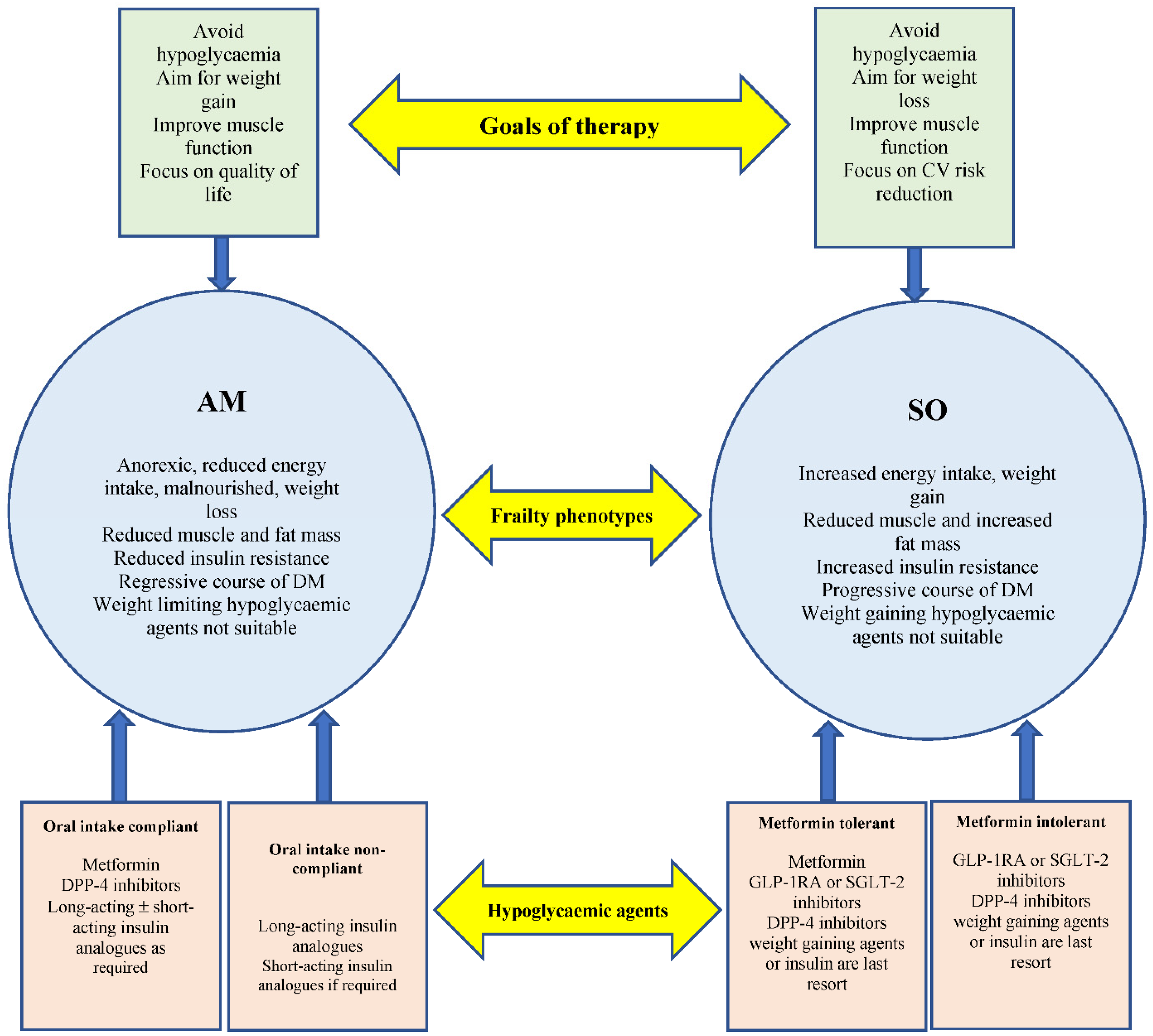

The potential effect on body weight should be considered when prescribing hypoglycaemic agents in frail older people with type 2 diabetes. For example, the use of weight limiting agents, such GLP-1RA and SGLT-2 inhibitors in the AM phenotype, are inappropriate due to the increased risk of further weight loss, dehydration, hypotension and increased risk of falls. Acarabose is associated with weight loss, significant gastrointestinal side effects and is less tolerated. Insulin secretagogues, such as sulfonylureas or glinides, although they have the advantage of desirable weight gain in the malnourished frail phenotype, are unsafe due to their high risk of hypoglycaemia. This population is also likely to have a high prevalence of dementia, which may be associated with erratic eating patterns, and the use of insulin secretagogues may significantly increase their risk of hypoglycaemia. Metformin may not be a suitable choice for many patients who have renal impairments. Additionally, pioglitazone is associated with the increased risk of lower-limb oedema, volume overload and exacerbation of congestive cardiac failure. Insulin has always been perceived as a last resort hypoglycaemic therapy after oral agents due to the associated side effects, such as the increased risk of hypoglycaemia, undesirable weight gain, inconvenience of frequent injections and the burden of blood glucose monitoring. However, in the AM phenotype of frailty, insulin may be a preferred early stage therapy. This phenotype is characterised by anorexia and significant weight loss. As a result, this phenotype has less insulin resistance and is likely to be more responsive to insulin therapy, in comparison to the SO phenotype that is characterised by increased insulin resistance [6]. Insulin-related weight gain is an advantage in this frailty phenotype. It may also have the potential to improve muscle mass and muscle function independent of glycaemic control. Therefore, in the milder form of the AM phenotype, such as people who are still compliant with oral therapy and nutrition, metformin, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors or glitazones can be used as first-line therapy, mainly due to their lower risk of hypoglycaemia. However, in patients with severe malnutrition and those less compliant with oral medications, insulin could be the first line of therapy. Insulin therapy has been shown to produce a sustained improvement in the well-being of older people [25]. Insulin-associated side effects, such as the inconvenience of frequent injections, blood glucose monitoring and the increased risk of hypoglycaemia, should be considered. The new insulin analogues appear as potentially favourable therapy in the AM frail phenotype due to the low risk of hypoglycaemia and the convenience of a once daily injection. In the SO phenotype, insulin therapy remains a last resort choice due to the significantly increased insulin resistance and undesirable weight gain in this phenotype. Metformin is the preferred first-line agent due to its cardiovascular benefits, weight-neutral effects and a potential positive effect on frailty [26][27]. GLP-1RA and SGLT-2 should be considered as a second-line, or first choice in patients not tolerant to metformin, due to their advantage of inducing significant weight loss and their cardio-renal protective effects [28]. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) is well tolerated with a low risk of hypoglycaemia or weight gain. Acarabose can be considered as an add-on therapy, if well tolerated. Although it can cause diarrhoea, it may have some cardiovascular benefits, low risk of hypoglycaemia and it promotes weight loss [29]. Insulin secretagogues and glitazones should be avoided in this frailty phenotype due to their increased risk of further weight gain (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Two main metabolic frailty phenotypes’ characteristics, hypoglycaemic agents and goals of therapy. Long-acting insulin analogues should be considered as an early option in AM frail patients with reduced and non-compliant oral intake. Weigh limiting agents should be considered as an early choice in the SO frailty phenotype. AM = Anorexic malnourished, SO = Sarcopenic obese.

References

- Sinclair, A.; Saeedi, P.; Kaundal, A.; Karuranga, S.; Malanda, B.; Williams, R. Diabetes and global ageing among 65–99-year-old adults: Findings from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 162, 108078.

- Sinclair, A.J.; Abdelhafiz, A.H.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Frailty and sarcopenia-newly emerging and high impact complications of diabetes. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 1465–1473.

- Hanlon, P.; Fauré, I.; Corcoran, N.; Butterly, E.; Lewsey, J.; McAllister, D.; Mair, F.S. Frailty measurement, prevalence, incidence, and clinical implications in people with diabetes: A systematic review and study-level meta-analysis. Lancet Health Longev. 2020, 1, e106–e116.

- Sinclair, A.J.; Abdelhafiz, A.; Dunning, T.; Izquierdo, M.; Manas, L.R.; Bourdel-Marchasson, I.; Morley, J.E.; Munshi, M.; Woo, J.; Vellas, B. An International Position Statement on the Management of Frailty in Diabetes Mellitus: Summary of Recommendations 2017. J. Frailty Aging 2018, 7, 10–20.

- Leroith, D.; Biessels, G.J.; Braithwaite, S.S.; Casanueva, F.F.; Draznin, B.; Halter, J.B.; Hirsch, I.B.; McDonnell, M.; Molitch, M.E.; Murad, M.H.E.; et al. TReatment of diabetes in older adults: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 1520–1574.

- Abdelhafiz, A.H.; Emmerton, D.; Sinclair, A.J. Impact of frailty metabolic phenotypes on the management of older people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2021, 21, 614–622.

- Rosenstock, J.; Schwartz, S.L.; Clark, C.M., Jr.; Park, G.D.; Donley, D.W.; Edwards, M.B. Basal insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes: 28-week comparison of insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH insulin. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 631–636.

- Riddle, M.C.; Rosenstock, J.; Gerich, J. Insulin Glargine 4002 Study Investigators. The treat-to-target trial: Randomized addition of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 3080–3086.

- Fritsche, A.; Schweitzer, M.A.; Häring, H.U.; 4001 Study Group. Glimepiride combined with morning insulin glargine, bedtime neutral protamine hagedorn insulin, or bedtime insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 138, 952–959.

- Haak, T.; Tiengo, A.; Draeger, E.; Suntum, M.; Waldhausl, W. Lower within-subject variability of fasting blood glucose and reduced weight gain with insulin detemir compared to NPH insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2005, 7, 56–64.

- Hermansen, K.; Davies, M.; Derezinski, T.; Martinez Ravn, G.; Clauson, P.; Home, P. A 26-week, randomized, parallel, treat-to-target trial comparing insulin detemir with NPH insulin as add-on therapy to oral glucose-lowering drugs in insulin-naïve people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1269–1274.

- Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Calvo, C.; Valbuena, H.; Ruiz, M.; Aschner, P.; Villena, J.; Ramirez, L.A.; Jimenez, J. Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes: Insulin Glargine vs. NPH Insulin Both in Combination with Glimepiride. Arch. Med. Res. 2006, 37, 495–501.

- Horvath, K.; Jeitler, K.; Berghold, A.; Ebrahim, S.H.; Gratzer, T.W.; Plank, J.; Kaiser, T.; Pieber, T.R.; Siebenhofer, A. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2007, CD005613.

- Singh, S.R.; Ahmad, F.; Lal, A.; Yu, C.; Bai, Z.; Bennett, H. Efficacy and safety of insulin analogues for the management of diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. CMAJ 2009, 180, 385–397.

- Fujimoto, K.; Iwakura, T.; Aburaya, M.; Matsuoka, N. Twice-daily insulin degludec/insulin aspart effectively improved morning and evening glucose levels and quality of life in patients previously treated with premixed insulin: An observational study. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2018, 10, 64.

- Lipska, K.J.; Parker, M.M.; Moffet, H.H.; Huang, E.S.; Karter, A.J. Association of Initiation of Basal Insulin Analogs vs Neutral Protamine Hagedorn Insulin with Hypoglycemia-Related Emergency Department Visits or Hospital Admissions and with Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA 2018, 320, 53–62.

- Haukka, J.; Hoti, F.; Erästö, P.; Saukkonen, T.; Mäkimattila, S.; Korhonen, P. Evaluation of the incidence and risk of hypoglycemic coma associated with selection of basal insulin in the treatment of diabetes: A Finnish register linkage study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2013, 22, 1326–1335.

- Strandberg, A.Y.; Khanfir, H.; Mäkimattila, S.; Saukkonen, T.; Strandberg, T.; Hoti, F. Insulins NPH, glargine, and detemir, and risk of severe hypoglycemia among working-age adults. Ann. Med. 2017, 49, 357–364.

- Bradley, M.C.; Chillarige, Y.; Lee, H.; Wu, X.; Parulekar, S.; Muthuri, S.; Wernecke, M.; MaCurdy, T.E.; Kelman, J.A.; Graham, D.J. Severe Hypoglycemia Risk with Long-Acting Insulin Analogs vs Neutral Protamine Hagedorn Insulin. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 598.

- Betônico, C.C.; Titan, S.M.O.; Lira, A.; Pelaes, T.S.; Correa-Giannella, M.L.C.; Nery, M.; Queiroz, M. Insulin Glargine U100 Improved Glycemic Control and Reduced Nocturnal Hypoglycemia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 3 and 4. Clin. Ther. 2019, 41, 2008–2020.

- Alsahli, M.; Gerich, J.E. Hypoglycemia in Patients with Diabetes and Renal Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 948–964.

- Pecoits-Filho, R.; Abensur, H.; Betônico, C.C.R.; Machado, A.D.; Parente, E.B.; Queiroz, M.; Salles, J.E.N.; Titan, S.; Vencio, S. Interactions between kidney disease and diabetes: Dangerous liaisons. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2016, 8, 50.

- Özçelik, S.; Çelik, M.; Vural, A.; Aydın, B.; Özçelik, M.; Gozu, M. Outcomes of transition from premixed and intensive insulin therapies to insulin aspart/degludec co-formulation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: A real-world experience. Arch. Med. Sci. 2021, 17, 1–8.

- Rodbard, H.W.; Cariou, B.; Pieber, T.R.; Endahl, L.A.; Zacho, J.; Cooper, J.G. Treatment intensification with an insulin degludec (IDeg)/insulin aspart (IAsp) co-formulation twice daily compared with basal IDeg and prandial IAsp in type 2 diabetes: A randomized, controlled phase III trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18, 274–280.

- Reza, M.; Taylor, C.; Towse, K.; Ward, J.; Hendra, T. Insulin improves well-being for selected elderly type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2002, 55, 201–207.

- Maruthur, N.M.; Tseng, E.; Hutfless, S.; Wilson, L.M.; Suarez-Cuervo, C.; Berger, Z.; Chu, Y.; Iyoha, E.; Segal, J.B.; Bolen, S. Diabetes Medications as Monotherapy or Metformin-Based Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 164, 740–751.

- Crowley, M.J.; Diamantidis, C.J.; McDuffie, J.R.; Cameron, C.B.; Stanifer, J.W.; Mock, C.K.; Wang, X.; Tang, S.; Nagi, A.; Kosinski, A.S.; et al. Clinical Outcomes of Metformin Use in Populations with Chronic Kidney Disease, Congestive Heart Failure, or Chronic Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 191–200.

- Abdelhafiz, A.H.; Sinclair, A.J. Cardio-renal protection in older people with diabetes with frailty and medical comorbidities—A focus on the new hypoglycaemic therapy. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2020, 34, 107639.

- Chang, Y.C.; Chuang, L.M.; Lin, J.W.; Chen, S.T.; Lai, M.S.; Chang, C.H. Cardiovascular risks associated with second-line oral antidiabetic agents added to metformin in patients with Type 2 diabetes: A nationwide cohort study. Diabet. Med. 2015, 32, 1460–1469.

More

Information

Subjects:

Medicine, General & Internal

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

563

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

04 Jul 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No