The exact date of his building the apparatus is not known but it appears to have been built sometime around 1897–1898. It found the first mention of his X-ray apparatus in a letter written to Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian to receive the Nobel Prize in literature, in February 1898

[12]. Unfortunately, neither the apparatus nor any sketch of his apparatus is available either at Presidency College, Calcutta, the place where he built the apparatus or at Bose Institute, Calcutta, the institute that he built later, to understand the mechanism of the apparatus. Fortunately,

scholars have been able to find a Press Report published on the 5th of May 1898 edition of the

Amrita Bazar Patrika, an erstwhile reputed English daily of India, under the title ‘Professor Bose and the New Light’ which describes the X-ray apparatus built by him and its demonstration.

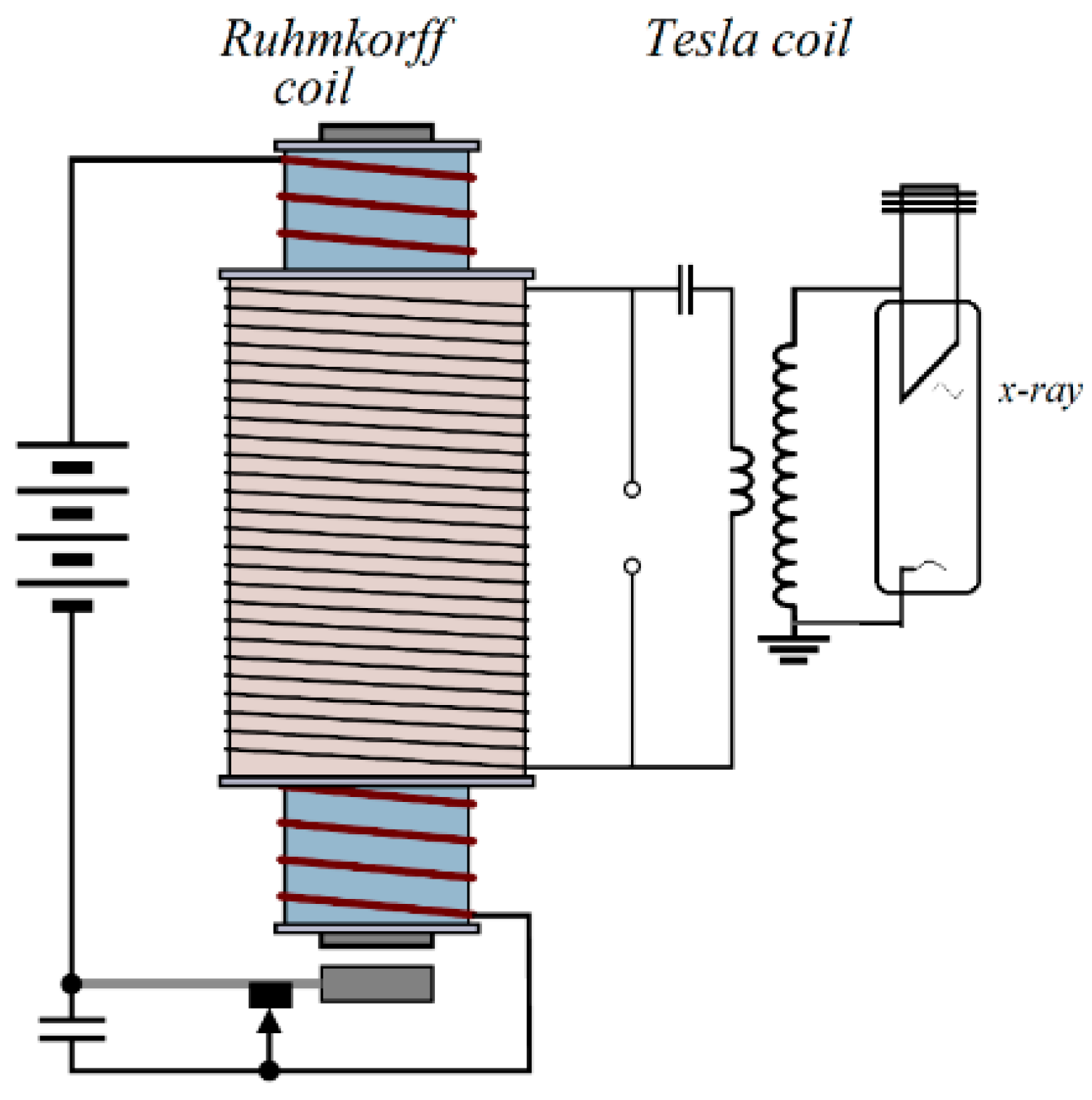

Roentgen used Ruhmkorff’s coil as a source of transient high voltage in discharging the gas in Crooke’s tube. Ruhmkorff’s coil produces high voltage pulse in the secondary coil by electromagnetic induction every time when a dc supply in the primary is interrupted by mechanical means. The secondary is connected with the discharge tube (X-ray tube) and the high voltage pulse was enough to produce X-rays. By coupling a Tesla coil with the secondary of Ruhmkorff’s coil (which then acts as the primary of the tesla transformer).

Jagadish Chandra had been able to produce a higher voltage many times more than that can be produced using a single Ruhmkorff’s coil. On the basis of the published information, scholars have presented a schematic diagram (Figure 2) to represent the apparatus he had probably used. The newspaper reported “We were shown a photograph of human palm taken by the Professor with the new light, and the ghastly sight will long be vividly imprinted in our memory, for there, in the photograph, instead of the ordinary fleshy palm is seen depicted a long range of bones presenting a skeleton-like appearance.” Using Barium Platinocyanide screen prepared by himself with his assistants in the Presidency College, he took X-ray photographs of different objects.

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the high voltage source J. C. Bose probably used.

Although use of X-rays in India was started within a few months of X-ray discovery by importing X-ray tube from abroad, commercial production of indigenous machine made in India started only a few years before India’s independence in 1947

[3].

4. Medical Uses of X-rays

As per available literature, the evidence of first clinical uses of X-rays in India, at least in an informal setting, was started by Jagadish Chandra Bose in 1898. In a letter (Sen, 1994) written possibly in February 1898 to Rabindranath Tagore, he expressed his inability to meet Rabindranath at a time when he will be busy examining a patient with a broken back using Roentgen

kal (machine in Bengali)

[12]. The history of application of X-rays by professionals for clinical purposes in India is not very clearly known. As reported

[13], Dr. Kartick Bose (1873–1955), an eminent doctor, medical scholar and industrialist was “the first clinician in India to start clinical and X-ray laboratories”.

Installation of the first X-ray machine in hospitals for public use is full of claims, counter-claims and conflicting reports so much so that it is very difficult to arrive at a definite conclusion

[5]. It was reported by K P Mody in one of his editorials published in the Indian Journal of Radiology & Imaging that “the first X-ray machine was imported by a chemist in 1902 into India; that was only 7 years after the discovery”

[14]. Madras Medical College website (

www.mmc.ac.in (accessed on 17 June 2021)) claimed that the “first X-ray outfit was obtained for the general hospital in the year 1900 almost five years after the discovery of X-rays, the first in South East Asia”. This might be true considering that it is a very old medical institution started first as a Government General Hospital on 16 November 1664 to treat sick soldiers of the East India Company.

Use of X-rays for therapeutical purposes was also carried out at the beginning of twentieth century. Successful treatment of leukaemia using X-rays was reported in

Calcutta Medical Journal [15] within five years of the first ever treatment of leukaemia, as reported in a paper published in the

Journal of the American Medical Association in 1902.

Excitement of using X-rays in medical science waned with time and was replaced by Xray research in physical sciences.

5. C.V. Raman and Initiation of X-ray Research in India

In July 1921, C.V. Raman (

Figure 3) on his voyage to England as a delegate of Calcutta and Banaras University to attend University Congress, was attracted to the “mystery of the blue colour of the sea”. On his return to India, he undertook a comprehensive programme of research on molecular scattering of light by solid, liquid and gases which led to the discovery of a new light effect. The new light effect was later known as ‘Raman effect’ and earned him the Nobel Prize in physics in 1930. During this time Raman and his students were interested in the study of optical anisotropy of molecules from scattering of light. Raman and Ramanathan

[16] extended the optical theory of scattering to X-ray diffraction by liquids. Experiments were also carried out to compare the theory with experimental results. Sogani

[17] recorded the X-ray diffraction patterns of 22 aliphatic and aromatic liquids and estimated the average molecular distance from the position of the maxima of the diffraction haloes. It became clear from these experiments that the shape of the molecules and the intermolecular forces had profound influence on the diffraction patterns. Krishnamurti

[18], another student of Raman, initiated small angle X-ray scattering which enabled people to understand the size and distribution of the particles in a sample. This is reportedly the first small angle X-ray scattering experiment performed in India

[19].

Raman had an encounter with William Bragg and he was of the opinion that Bragg’s first structure of naphthalene was not consistent with the birefringence, while the second one was. In order to confirm this, he and his students started extensive studies on the optical and magnetic anisotropy of organic crystals to understand the arrangements of molecules in crystalline state. The work on crystal magnetism was initiated by one of his successful students K.S. Krishnan. In many cases the orientation of the molecules in the unit cell could be calculated with a high degree of precision from purely magnetic data, which helped in refining X-ray analysis of the crystal structure

[20][21].

Bidhubhusan Ray, another student of Raman, made significant contribution to X-ray spectroscopy, although he remained unknown to most physicists until a book was published by Rajinder Singh

[22]. Bidhubhushan Ray (B. B. Ray) worked with Manne Siegbahn, a Nobel Laureate in Physics, at Uppsala and on his return to India established X-ray laboratory at Calcutta University. Satyendranath Bose who visited Europe during 1924–1926 met de Broglie brothers and was attracted to X-ray crystal structure. His experience was utilized both at Dhaka University and later at the Calcutta University where he took charge of the X-ray laboratory after the premature death of B. B. Ray and built an X-ray diffraction apparatus in the laboratory (

Figure 4).

Figure 4. X-ray Diffraction Apparatus built by SN Bose. (Courtesy: Prof. Alok Mukherjee).

Historically the first crystallographic activity in India started with the determination of crystal structures of napthaelene and anthracene by Kedareswar Banerjee (KB) at IACS

[23][24]. In 1930, in response to KB’s article in “Nature” on the structure of naphthalene, J.M. Robertson of Michigan University, Ann Arbor, U.S.A., wrote: “I believe Dr. Banerjee’s structure to be essentially correct. It has been clear to me for some time that the last two sections of my paper to which Dr. Banerjee refers must be amended as regards the distribution of the scattering centres in the a and b directions”. His further research on crystallography paved the way for a ‘complete crystallography structure analysis’ and for understanding statistical relationships in the amplitudes of diffracted waves. Further details of his life and work are available in a recently published book

[25].

With Raman having good contact with the giants in the field of X-ray crystallography, he was able to send many of his students abroad to let them work with leading scientists of the field to gain contemporary knowledge of the subject. This made IACS the nucleus of X-ray research in India.

After independence, there has been a great surge of scientific research in India through establishment of laboratories by the Govt. of India. X-ray crystallography also flourished and expanded into areas of biological sciences. Contributions of Kedareswar Banerjee were followed by equally profound works by other researchers in India such as G. N. Ramachandran (University of Madras and Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore), A. R. Verma (Banaras Hindu University), S. Ramashesan (National Aeronautical Laboratory, Bangalore), VR. Chidambaram (Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, Mumbai) and others

[26].

G.N. Ramachandran, a student of C.V. Raman, and most distinguished crystallographer of independent India worked on fibrous proteins and was recognized for the advancement of triple helix model of the structure of collagen

[27] and the Ramachandran plot for validation of protein structure.