Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ivan Santolalla Arnedo | -- | 3037 | 2022-06-14 16:53:09 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -9 word(s) | 3028 | 2022-06-15 03:02:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Santolalla Arnedo, I.; Sufrate-Sorzano, T.; Jiménez Ramón, E.; Garrote Cámara, M.; Gea-Caballero, V.; Durante, �.; Juárez-Vela,Md, R. Health Plans for Suicide Prevention in Spain. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24025 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Santolalla Arnedo I, Sufrate-Sorzano T, Jiménez Ramón E, Garrote Cámara M, Gea-Caballero V, Durante �, et al. Health Plans for Suicide Prevention in Spain. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24025. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Santolalla Arnedo, Ivan, Teresa Sufrate-Sorzano, Elena Jiménez Ramón, Maria Garrote Cámara, Vicente Gea-Caballero, Ángela Durante, Raúl Juárez-Vela,Md. "Health Plans for Suicide Prevention in Spain" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24025 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Santolalla Arnedo, I., Sufrate-Sorzano, T., Jiménez Ramón, E., Garrote Cámara, M., Gea-Caballero, V., Durante, �., & Juárez-Vela,Md, R. (2022, June 14). Health Plans for Suicide Prevention in Spain. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/24025

Santolalla Arnedo, Ivan, et al. "Health Plans for Suicide Prevention in Spain." Encyclopedia. Web. 14 June, 2022.

Copy Citation

Suicide is a serious health problem affecting people of all ages and in all countries. Suicide prevention, listed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) as a global imperative, has grown in importance in recent years to become a priority task in global public health. Suicide death rates are high, with an estimated 800,000 deaths by suicide each year.

suicide

prevention

risk factors

health care plan/programme

1. Health care Plans as a Preventive Measure against Suicide

National prevention strategies must be resourced and periodically re-evaluated to take account of evolving societal changes [1]. In addition to these strategies, health plans for suicide prevention developed by each province are essential to reinforce general preventive measures and adapt them to the type of population and resources of each community [2]. The elaboration of these preventive strategies and plans is a highly relevant act of research and data collection as measures are put in place. This allows the identification of at-risk and vulnerable groups; of the needs of the population; of gaps in current knowledge; and of the main risk, precipitating and protective factors for each group. This allows interventions to be tailored according to the needs of the provinces [1][2].

The year 2020 was the year with the highest number of suicides in the history of Spain since data have been recorded, totalling 3941 people, which is an average of 11 suicides per day or one every 2.2 h [3][4]. This is why it is necessary to analyse and discern points for improvement.

Suicide prevention involves not only the health sector, but also several key sectors such as social services, education and politics, as well as society as a whole. Therefore, the WHO encourages governments to invest in multisectoral strategies to reduce the rates of suicide deaths and suicide attempts [1].

Since 2000, several countries have developed preventive strategies against suicide. Spain is one of them, having created the Clinical Practice Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behaviour in 2012, which was revised in 2020 by a group of experts who considered maintaining the validity of the proposed interventions [5]. This guide addresses important issues such as the care and attention of the different sectors involved, as well as preventive measures. It also includes screening and identification of risk groups, promotion of the development of protective factors, restriction of access to lethal means, training programmes for health and non-health personnel, information for media professionals, care for family members and relatives and the development of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [5][6]. In Spain, all provinces agree with the statement published by the WHO declaring suicide and its associated behaviours as preventable acts if appropriate measures are taken in the vulnerable population [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29].

2. General Interventions

In the group of general interventions, the plans of the province of Asturias and Castilla y León are excluded as they are documents aimed at health professionals and, therefore, their interventions are focused on this area [11][15].

Awareness-raising among the general population is applied in all provinces and cities except the Balearic Islands, which focuses on other preventive aspects. To promote public awareness, most communities propose activities on key days related to suicide such as 10 September (World Suicide Prevention Day) and actions to improve the detection of suicidal risk in order to enable the population to recognise risk factors and enable the early detection of suicidal ideation. On the other hand, the population is also provided with truthful information and scientific evidence on social networks and official websites, in addition to the fact that most communities are equipped with an extensive infrastructure for telephone assistance and help contacts. The province of Aragon focuses especially on telematic care and the use of new technologies to raise awareness among the general population due to the arrival of the pandemic caused by COVID-19 [9][10][11][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26].

The regions of Extremadura and Murcia, on the other hand, only include in this section the detection of risk factors in vulnerable groups [21][24].

Approximately 65% of the communities (Andalusia, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Cantabria, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Navarre, Basque Country and Valencia) mention among their general interventions the importance of placing restrictions on potentially lethal means. These measures are comprehensive in nature as they integrate several aspects. All the plans that mention measures related to restricting access to lethal means agree that the epidemiology of suicide in the area must be known in order to prevent the development of new cases that follow the same methodology of suicide [7][8][9][10][12][13][14][22][23][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35].

Several communities add the surveillance of dangerous places considered as “suicide black spots” due to the accumulation of several deaths due to suicide. Architectural barriers are proposed to be installed to prevent and/or hinder access to these sites, as most of them are high-rise areas [8][9][10][12][22][36][37].

Pharmacological control and vigilance are closely related to health interventions, consisting of ensuring that the medication guidelines for people at risk of suicide are correct and appropriate. In relation to the control of doses and their administration, preventive measures are mentioned in the plans of 8 of the 17 provinces: Andalusia, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Navarre and the Basque Country. The province of Madrid lists control of access to drugs as its main measure in terms of restricting access to lethal drugs [7][8][9][10][12][22][23][25][26].

Inter-institutional coordination is essential for the development of preventive measures, both in the health system and at the social level. This is why almost 83% of the provinces include this aspect among the proposed interventions. Most of them propose the improvement of their coordination strategies both at a territorial level and between the different disciplines related to the detection and approach to suicide and related behaviours. The main institutions referred to by most communities are health centres, educational centres, socio-health centres and security forces, such as police or fire brigades. Collaboration with prisons and coordination with the state and public administrations in arranging new measures such as patient associations or mutual help groups are also mentioned [8][9][10][13][14][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27].

Some provinces have created, or propose to create, the formation of working groups whose functions are exclusively aimed at guaranteeing and monitoring coordination between the different bodies and services involved in order to improve suicide prevention [7][22][25][26].

Asturias, in proposing a prevention plan focused on health care, establishes coordination measures, but refers only to the different points of health care and the relationship of continuity that they should have [11]. The measures proposed for the development of a suicide prevention plan in the Balearic Islands’ Strategic Plan for Mental Health concern broader measures, but coincide with Asturias in terms of the health care approach to coordination [12].

More than half of the Spanish provinces agree on the need to improve research related to suicide and self-injurious behaviour. In this way, facilities are proposed to prevent suicide in vulnerable people or those with associated pathologies such as depression. Alongside this improved research, epidemiological surveillance and its major impact on the effectiveness of preventive interventions within the community are discussed. To this end, the communities of Aragon, Baleares, Canarias, Cantabria, Castilla La Mancha, Cataluña, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Madrid, Navarre, País Vasco and Valencia allude to an improvement in recording cases of death by suicide by means of periodic reports or data-recording strategies such as the use of psychological highways, this being the technique that is most frequently reiterated throughout the plans presented [7][9][10][12][13][14][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][25][26][27][28][29][30].

To strengthen epidemiological surveillance, the Spanish Foundation for Suicide Prevention has created an organisation, the Spanish Suicide Observatory, whose mission encompasses the analysis and dissemination of epidemiological data related to suicide in order to enable its prevention. Many of the provinces have decided to create a Suicide Observatory at the provincial level to extract data specific to their area [3].

3. Training Interventions

The communities of Asturias and Castilla y León, as in the group of general interventions, are excluded from the group of training interventions, focusing only on how to deal with a crisis situation on the part of health personnel [11][15].

The most frequently mentioned risk group with which training activities are intended to be carried out is the school environment. All communities except Asturias, Cantabria, Castilla y León, Extremadura, Madrid and Murcia propose workshops and courses aimed at both schoolteachers and pupils. The main objective of these training workshops is to train teachers to detect and deal with possible cases of suicidal behaviour and crisis situations, in order to increase their knowledge related to the identification of risk factors and the strengthening of protective factors, as well as to guide students not only in the detection of possible cases, but also in the correct mutual support among them, forming mutual help groups in the classroom and improving their coping skills [7][8][9][10][12][13][16][17][18][19][20][22][25][26][27]. The autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla consider strengthening emotional education from the school years onwards as a measure to be included in their future prevention plans [28][29].

In addition, training actions aimed at other groups such as adolescents, survivors in cases of death of a loved one due to suicide, the elderly and their informal carers, inmates in penitentiary centres and people in situations of discrimination or violence of any kind are mentioned. People suffering from Severe Mental Disorder (SMD) are added as one of the main vulnerable groups receiving the necessary information primarily from mental health centres [7][8][9][10][12][13][16][17][18][19][20][22][25][26][27].

The province of La Rioja includes the main activities to be carried out in schools, penitentiary centres, juvenile centres, centres for the elderly and in the field of forensic medicine [22]. In addition, the Suicide Prevention Strategy of Aragon includes the university population as a vulnerable group due to the psychological distress of students experiencing states of anxiety, social dysfunction and even symptoms compatible with depression [9][10].

Training aimed at health care professionals focuses on keeping current information up to date, as well as training staff to identify early risk and warning signs using indicators, improving clinical interview techniques to obtain more accurate information, making appropriate referrals between services by promoting coordination and agreeing on unified protocols and procedures. To this end, continuous face-to-face, blended and online training activities are presented [8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27].

Both the 17 provinces and the two autonomous cities agree to carry out these activities aimed at health personnel [8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]. Asturias and Castilla y León, as mentioned in previous paragraphs, dedicate their plan exclusively to actions by the health sector in risk situations and do not explicitly mention training for this group. At the same time, they propose interventions for which this training is necessary, such as the use of the clinical interview or the recognition of risk factors [11][15].

It also shows the trend towards the development of training work among non-health professionals, which is defined in 12 of the 17 Spanish provinces. A general mention is made of the group of non-health professionals in relation to at-risk patients or vulnerable groups, although the importance of providing adequate training for social service workers, social health and security forces, including police and firefighters, is highlighted [7][8][12][13][14][17][20][22][23][25][26][27]. In addition, the strategy for suicide prevention in the Basque Country incorporates the promotion of psychological first aid in these interventions, as well as training aimed at staff providing telephone assistance to people at risk [26].

Finally, around 71% of the provinces include training interventions together with the dissemination of information and recommendations for the media, so that an adequate approach to suicide in the press is possible, one that does not have a negative impact on suicide rates [8][9][10][12][14][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][25][26]. One of the main concerns reported by the WHO is the ease with which the general population can access inappropriate information related to suicidal practices through the media and the internet. WHO includes the following objective among the components that should be included in national strategies: “Promote implementation of media guidelines to support responsible reporting of suicide in print, broadcasting and social media” [1][30].

The WHO document “Preventing suicide” emphasises collaboration and educational engagement with the media to achieve this goal. It also describes preventive measures related to responsible communication in the media, including interventions such as the use of responsible language; dissemination of information about available treatments; information about organisations, mobile apps and social networks as support mechanisms; and avoiding sensationalism, simplification or detailed description of the event [1].

4. Health Interventions

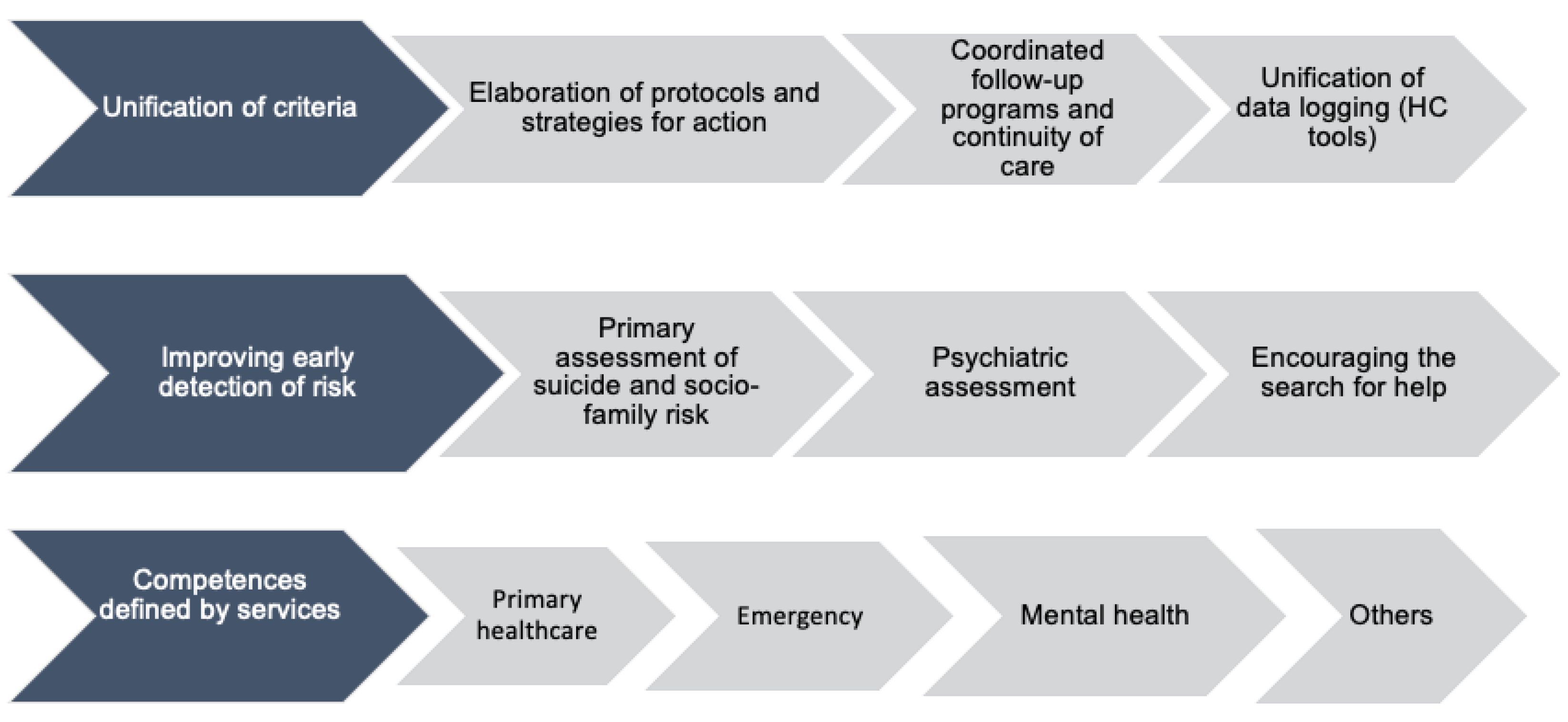

To improve the rates of early detection of risk (Figure 1), all communities except the Balearic and Canary Islands agree that it is necessary to improve assessment techniques, mainly those used in the first care received by patients, in order to identify the problem as early as possible and the risk factors that may lead to suicidal behaviour and act accordingly [6][7][8][9][10][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]. To this end, the plans of several communities focus on the risk assessment carried out in primary care and emergency and telephone services together with the emergency psychiatric assessment carried out by mental health professionals once an indication of risk has been detected at earlier points in the care chain, cited in the plans of Andalusia, Castilla y León, Catalonia and La Rioja [8][15][17][18][19][20][22].

Figure 1. Classification of health interventions.

Another point to be taken into account in improving risk assessment is the appropriate use of tools such as indicators included in clinical history, assessment scales and improved clinical interview techniques. The regions that are most focused on these elements are Castilla y León and Navarre (adding physical examination), followed by Asturias and Galicia, whose plans focus exclusively on standardised assessment scales [7][11][15][25].

The detection of risk factors is an element to be considered in the assessment of each patient. On numerous occasions, it is related to the socio-family situation of the victim, an aspect mentioned only by the Protocol for Detection and Case Management in Persons at Risk of Suicide in Asturias [14], while the detection and approach to risk factors in vulnerable groups are dealt with by four of the seventeen provinces [7][8][22][25].

To complement the detection of risk and improve the quality of care, almost 24% of the communities suggest that professionals who detect risk should encourage help-seeking and the active participation of the patient [6][7][8][9][15][24]. In addition, Castilla La Mancha and Navarre promote protective factors and healthy lifestyle habits, respectively [16][25].

In order to achieve the unification of criteria, all communities agree on the need to draw up guidelines and protocols that dictate how to act in certain situations related to suicidal behaviour [8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27].

Andalusia, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, Castilla La Mancha, Extremadura and Navarre propose the implementation of action plans in the different hospital services with the aim of homogenising the criteria for action [8][12][13][16][21][25]. La Rioja includes the activities of other institutions in addition to health services, such as educational, penitentiary, juvenile, elderly and forensic medicine centres [22]. La Rioja, Aragon, Castilla y León, Madrid and Murcia focus their future programmes on patient safety, as well as on creating individualised plans at discharge, during hospitalisation and involving the family [9][13][15][22][23][24]. Extremadura includes the consideration of suicidal risk in other action plans such as Cancer or Drug Dependency [21].

The implementation of suicide codes is present in 4 of the 17 provinces [7][17][18][19][20][21][26]. In the Canary Islands, a suicide risk code protocol is not specifically established, but the Mental Health Plan mentions the creation of a crisis line with a suicide risk hotline [13].

In relation to the development of patient follow-up protocols and ensuring continuity of care during the process, 82% of the Spanish provinces mention related interventions in their plans. Most establish time periods in which to provide initial care on arrival of the patient, when the risk is identified, or the time between the patient’s discharge and the next consultation. In general, the plans establish a time period of between 24 h and 7 days for the initiation of patient follow-up either by telephone or face-to-face consultations. Most of them also agree on the duration of the follow-up process, extending it for at least 12 months, with the exception of Navarre, which establishes a follow-up of at least 6 months [7][8][9][10][11][12][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][27]. The protocol for the detection and case management of people at risk of suicide in Asturias establishes in greater detail the time periods and how to contact the patient during follow-up [11]. In the La Rioja Suicide Prevention Plan, only weekly visits are mentioned in terms of time periods for follow-up, and the documents drafted by the Balearic Islands, Castilla La Mancha and Murcia do not establish time periods for the proposed follow-up [12][16][22][24].

In this follow-up, the family is involved in addition to monitoring the patient and the access to dangerous means such as pharmacological control during their dispensation while the patient is hospitalised and when he/she is discharged. In any case, but especially in those involving family and relatives, it is necessary to maintain confidentiality and obtain informed consent from the patient, as their problem will be discussed with other people. Not all regions highlight this aspect, but Castilla y León, Catalonia and Navarre mention it in their plans [15][17][18][19][20][25].

With regard to the unification of criteria, it is also necessary to add the homogenised registration of cases with tools and forms available in the clinical history, in order to facilitate the development of better research into the epidemiology of suicide in each community. This is only proposed in five provinces: Asturias, Castilla y León, Madrid, Murcia and Euskadi [11][15][23][24][26].

Thirty-five percent of the communities specifically describe the competences of the priority health services, both preventive and in suicidal crises [8][15][16][23][24][25]. The plans of the provinces of Asturias and Navarre describe the care to be provided by nursing staff in cases of suicidal behaviour or suicide, the most frequent actions being telephone follow-up, surveillance and supervision, pharmacological administration and control, cognitive behavioural therapy, emotional support and active listening, identification of personal risks, involvement of the family in care, promotion of healthy habits and environmental management [11][25].

Likewise, the Canary Islands propose the possibility of creating an Ultra Short Stay Unit in the different provinces for patients with considerable and uncertain risk [13], and Navarre adds the interventions to be carried out by social services and the creation of a specific partial hospitalisation device for psychogeriatrics [25].

Finally, La Rioja and Galicia include care for professionals involved in dealing with cases of suicide [8][22]. This is known as “debriefing”, a technique in which reflection and emotion management are worked on through the communication of staff involved in traumatic events such as, the death of a patient due to suicide, as the actions taken and decisions made during the care process are re-evaluated, making it possible to detect errors in order to improve them in the future [31].

References

- Saxena, S.; Krug, E.G. Suicide Prevention: A Global Imperative; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Dumon, E.; Portzky, G. General Guidelines for Suicide Prevention; European Regions Enforcing Actions Against Suicide; Universidad de Gante: Gante, Belgium, 2013.

- Spanish Foundation for Suicide Prevention. Observatory of Suicide in Spain. Available online: https://www.fsme.es/observatorio-del-suicidio/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- National Statistics Institute. Statistical Organisation in Spain. España. Available online: https://www.ine.es/CDINEbase/consultar.do?mes=&operacion=Defunciones+seg%FAn+la+Causa+de+Muerte&id_oper=Ir (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Working Group for the revision of the Clinical Practice Guideline on the prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour. Revision of the Clinical Practice Guideline on the Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behaviour of the NHS CPG Programme, 1st ed.; Galician Agency for Health Technology Assessment (AVALIA-T): Madrid, Spain, 2020.

- General Council of Psychology of Spain. Published the revision of the Clinical Practice Guideline on Prevention and Treatment of Suicidal Behaviour. Available online: http://www.infocop.es/view_article.asp?id=15063&cat=47 (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Xunta de Galicia. Suicide Prevention Plan in Galicia, 1st ed.; Conselleria de Sanidade: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2017; p. 65.

- Servicio Andaluz de Salud. Recommendations on the Detection, Prevention and Intervention of Suicidal Behaviour, 1st ed.; Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública: Granada, Spain, 2010; 113p.

- Professional Association of Psychology of Aragon, Aragon Telephone of Hope, Association of Journalists of Aragon, National Association of Health Informants. Information guide for the detection and prevention of suicide: Concepts and guidelines for citizens, family members and those affected in Aragon. 2020. Available online: https://www.cop.es/pdf/Guia-digital.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Working Group of the Suicide Prevention Strategy in Aragon. Estrategia de Prevención del Suicidio en Aragón, 1st ed.; Gobierno de Aragón: Aragón, Spain, 2020.

- Working group of the Protocol for the detection and management of cases of people at risk of suicide. Protocol for the detection and management of cases of people at risk of suicide. Regional Ministry of Health (Coordination Unit of the Mental Health Framework Programme SESPA), 2018. Available online: https://cendocps.carm.es/documentacion/2019_Protocolo_deteccion_manejo_caso_suicidio.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Working Group of the Strategic Mental Health Plan of the Balearic Islands. Strategic Plan for Mental Health in the Balearic Islands 2016–2022, 1st ed.; Conselleria Servei Salut: Mallorca, Illes Balears, Spain, 2016; pp. 31–32.

- Servicio Canario de Salud. Canary Islands Mental Health Plan 2019–2023, 1st ed.; Gobierno de Canarias: Gran Canaria, Canary Island, Spain, 2019; pp. 247–255.

- Working Group of the Mental Health Plan of Cantabria. Mental Health Plan of Cantabria 2015–2019, 1st ed.; Gobierno de Cantabria, Consejería de Sanidad y Servicios Sociales: Santander, Cantabria, Spain, 2014; pp. 49–56.

- Working Group of the Process of Prevention And Care Of Suicidal Behaviour. Process of Prevention and Care of Suicidal Behaviour, 1st ed.; Junta de Castilla y León: León, Castilla y León, Spain, 2020.

- Regional Working Group on Suicide Prevention in Castilla-La Mancha. Strategies for Suicide Prevention and Intervention in the Face of Self-Harm Attempts in Castilla-La Mancha, 1st ed.; Gobierno de Castilla La Mancha: Toledo, Spain, 2018.

- Grupo de trabajo del Pla de Salut de Catalunya. Pla de Salut de Catalunya 2016–2020, un Sistema Centrat en la Persona: Públic, Universal I Just, 1st ed.; Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Salut: Barcelona, Cataluña, Spain, 2016.

- Grupo de trabajo del Pla de Salut de Catalunya. Plan de Salud de Cataluña 2011–2015, 1st ed.; Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Salut: Barcelona, Cataluña, Spain, 2012.

- Servei Català de la Salut. Atenció a Les Persones En Risc De Suïcidi: Codi Risc de Suïcidi. Available online: https://catsalut.gencat.cat/ca/detalls/articles/instruccio-10–2015 (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Salut. European Project against Depression and Suicide Prevention; Departament de Salut, Direcció General de Planificació i Avaluació: Barcelona, Cataluña, Spain, 2007.

- Extremadura Health Service. I Plan de Acción para la Prevención y Abordaje de las Conductas Suicidas en Extremadura; Directorate General for Health Care: Extremadura, Spain, 2018.

- Working group of the Suicide Prevention Plan in La Rioja. Suicide Prevention Plan in La Rioja, 1st ed.; Gobierno de La Rioja: Logroño, La Rioja, Spain, 2018.

- Working Group of the Strategic Plan for Mental Health in the Region of Madrid. Strategic Plan for Mental Health in the Region of Madrid 2018–2020, 1st ed.; Servicio Madrileño de Salud: Madrid, Spain, 2018.

- De Concepción Salesa, A.; Hurtado López, A.M.; Martínez Serran, J.; Ortiz Martínez, A. Programme of Action for the Promotion and Improvement Of Mental Health in the CARM 2019–2022; Gerencia Regional de Salud Mental: Murcia, Spain, 2018; pp. 112–115.

- Working group of the Interinstitutional Collaboration Protocol. Suicidal Behaviour Prevention and Action: Interinstitutional Collaboration Protocol, 1st ed.; Gobierno de Navarra: Pamplona, Navarra, Spain, 2014.

- Department of Health, Basque Government and Osakidetza. Suicide Prevention Strategy in the Basque Country; Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco: Vitoria, Pais Vasco, Spain, 2019.

- Working group of the Suicide Prevention and Suicidal Behaviour Management Plan of the Valencian Community. Living is the Way Out: Suicide Prevention and Suicidal Behaviour Management Plan, 1st ed.; Conselleria de Sanitat Universal i Salut Pública: Valencia, Comunidad Valenciana, Spain, 2017.

- The Ceuta Forum editorial team. The elaboration of a National Plan for Suicide Prevention is more necessary than ever. Available online: https://elforodeceuta.es/la-elaboracion-de-un-plan-nacional-para-la-prevencion-del-suicidio-es-mas-necesaria-que-nunca/ (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Popular Editor. FEAFES Melilla Advocates the Creation of a National Suicide Prevention Plan. Available online: http://populartvmelilla.com/archivos/2248 (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Herrera-Ramírez, R.; Ures-Villar, M.B. The treatment of suicide in the Spanish press: The werther effect or the papageno effect? Rev. Asoc. Esp. Neuropsiq. 2015, 35, 123–134.

- Ugwu, C.V.; Medows, M. Critical Event Debriefing in a Community Hospital. Cureus 2020, 25, 12.

- Gesteira, C.; Beunza, J.J.; Rodríguez Rey, R.; de Pascual Verdú, R.; Hurtado, C. Suicide Trends by Gender, Methods of Suicide and Age in Spain between 2005 and 2018; Universidad Pontificia Comillas: Madrid, Spain, 2021.

- Castellvi-Obiols, P.; Piqueras-Rodríguez, J.A. Adolescent suicide: A preventable and preventable public health problem. Rev. Estud. Juv. 2018, 121, 45–59.

- Hernández-Soto, P.A.; Villarreal-Casate, R.E. Some specificities around suicidal behaviour. MEDISAN 2015, 19, 1051–1058.

- Blanco, C. Suicide in Spain. Institutional and social response. Rev. Estud. Soc. 2020, 33, 79–106.

- Clayton, P.J. MSD Manual, Version for Professionals, 1st ed.; University of Minnesota School of Medicine: Delaware, MN, USA, 2019.

- Gabilondo, A. Suicide prevention, review of the WHO model and reflection on its development in Spain: SESPAS Report. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 34, 27–33.

More

Information

Subjects:

Nursing

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

650

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No