Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | oluwatobi owojori | -- | 1290 | 2022-05-31 23:21:02 | | | |

| 2 | oluwatobi owojori | Meta information modification | 1290 | 2022-05-31 23:24:46 | | | | |

| 3 | Dean Liu | -55 word(s) | 1235 | 2022-06-01 03:32:47 | | | | |

| 4 | Dean Liu | -1 word(s) | 1234 | 2022-06-02 08:49:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Owojori, O.; Okoro, C. Circular Economy in the Built Environment. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23627 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Owojori O, Okoro C. Circular Economy in the Built Environment. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23627. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Owojori, Oluwatobi, Chioma Okoro. "Circular Economy in the Built Environment" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23627 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Owojori, O., & Okoro, C. (2022, May 31). Circular Economy in the Built Environment. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23627

Owojori, Oluwatobi and Chioma Okoro. "Circular Economy in the Built Environment." Encyclopedia. Web. 31 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

The circular economy (CE) is a paradigm that is becoming increasingly popular to drive the movement to sustainability, requiring the partnership of the private sector to be implemented successfully. The application of CE initiatives in the private sector engagement has received less attention. The private sector is critical to achieving the sustainable development goals (SDGs) and the 2030 Agenda by interacting with societies, governments, and other actors for a circular built environment.

private sector

public–private partnership

circular economy

scientometrics

built evironment

adaptive reuse

buildings

1. Introduction

The building and construction industry consumes 40% of total natural resources globally, generates 40% of worldwide waste, and emits 33% of global emissions [1], making it the world’s greatest user of raw resources. It produces 50% of the world’s steel and consumes about 3 billion tons of raw materials. The world’s population is predicted to grow from two to five billion people by 2030, putting more strain on resource usage. This will add to the existing demand for housing and services [2].

Cities have remained hubs of activity in recent years, luring billions of new residents. By 2050, the global urban population is predicted to increase by 3 billion people [3]. Given that 60% of the area predicted to be urban by 2030 is yet to be created, one can envision the enormous demand that this will place on existing and future infrastructure. Incorporating CE principles across the sector has evident benefits. As a first step toward shifting to circularity in the built environment, this would entail changing how projects are designed, constructed, maintained, and recycled.

Since the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s CE study in 2012, scholars and practitioners have lauded the CE concept as the best strategy to prevent the consequences of the linear economy, as well as operational traction toward the overused term of sustainable development [4]. The advantages of a CE have been researched in previous research. For example, McDonough and Braungart [5] expressed that when the CE is completely implemented, it will ensure that technical and biological elements are safely returned to the industrial system and environment. The CE concept also leads to the use of renewable energy in manufacturing systems [4] and the application of innovative business models that catalyze collaboration and technological innovation. Thus, several global cities demonstrate their devotion and intellectual capacity to develop the CE.

Some strategies, such as those used in Amsterdam, focusing on built environment solutions, such as creating CE buildings and commercial areas, exist. Amsterdam is speeding up its transformation to become one of the first CE cities in the world. Towards the Amsterdam Circular Economy and the City Circle are two examples of such initiatives [6], while other cities and localities, on the other hand, have launched specialized programs that employ CE ideas in a variety of ways. In Paris, the city approaches CE via a social and cohesive economy method emphasizing socioeconomic priorities, including sharing above profit, communal intelligence, and mobilizing local governments and individuals [7]. Peterborough, in the United Kingdom (UK), has announced that it wants to be the country’s first circular city. Peterborough DNA, the organization driving the program, is based on concepts such as systems thinking, urban metabolism, and biomimicry. It takes a bottom-up, collaborative approach to build and maintain circular approaches, with local stakeholders playing a key role. It emphasizes municipal systems and networks, including water, electricity, resources, local skills, transportation, education, healthcare, neighborhoods, recreational activities, and other municipal services [8]. However, due to the vast size of the development and resources required, the public sector (government) is under pressure because of the ensuing tightening of state development budgets and the magnitude of global development difficulties. The focus has thus shifted to the private sector to increase finances and offer expertise and knowledge to address associated issues [9][10].

Several solutions to the building and construction industry’s circularity and delivery difficulties have been top-down, government-driven actions. While such an approach has its merit, various approaches, including multi-stakeholder cooperation in circular networks to produce unique solutions, could be considered. The application of CE concepts to the built environment is still in its early stages of development [11]. As a result, in conformance with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable [12], public–private partnership (PPP) is currently a rapidly expanding form of collaboration that interconnects infrastructure gaps around crucial city services and utilities such as transportation, healthcare, and power supply [13]. Furthermore, the necessity of adopting multi-actor collaborations and stakeholders’ involvement and participation is emphasized, as it is a stand-alone target, SDG 17 “partnerships for the goals,” in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This target 17;17, in particular, develops and promotes effective public–private collaborations [12].

Gatherings of international leaders, including local representatives, NGOs, and private industry actors, at the three major United Nations conferences on Sustainable Development have helped to frame these trends during the last few decades, such as in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, 2002 in Johannesburg, and 2012 at the Rio + 20 conference. During these sessions, the private sector’s growing position as a development actor was emphasized. For example, the Johannesburg Declaration stated that “the private sector, including both big and small firms, has a duty to contribute to the evolvement of sustainable and equitable communities and societies” [10][14]. Also emphasized in the Rio + 20 policy statement is that the private sector must contribute to the advancement of inclusive and sustainable communities and societies [10][14]. Therefore, research on private sector participation is warranted.

2. Brief History of the CE and Built Environment

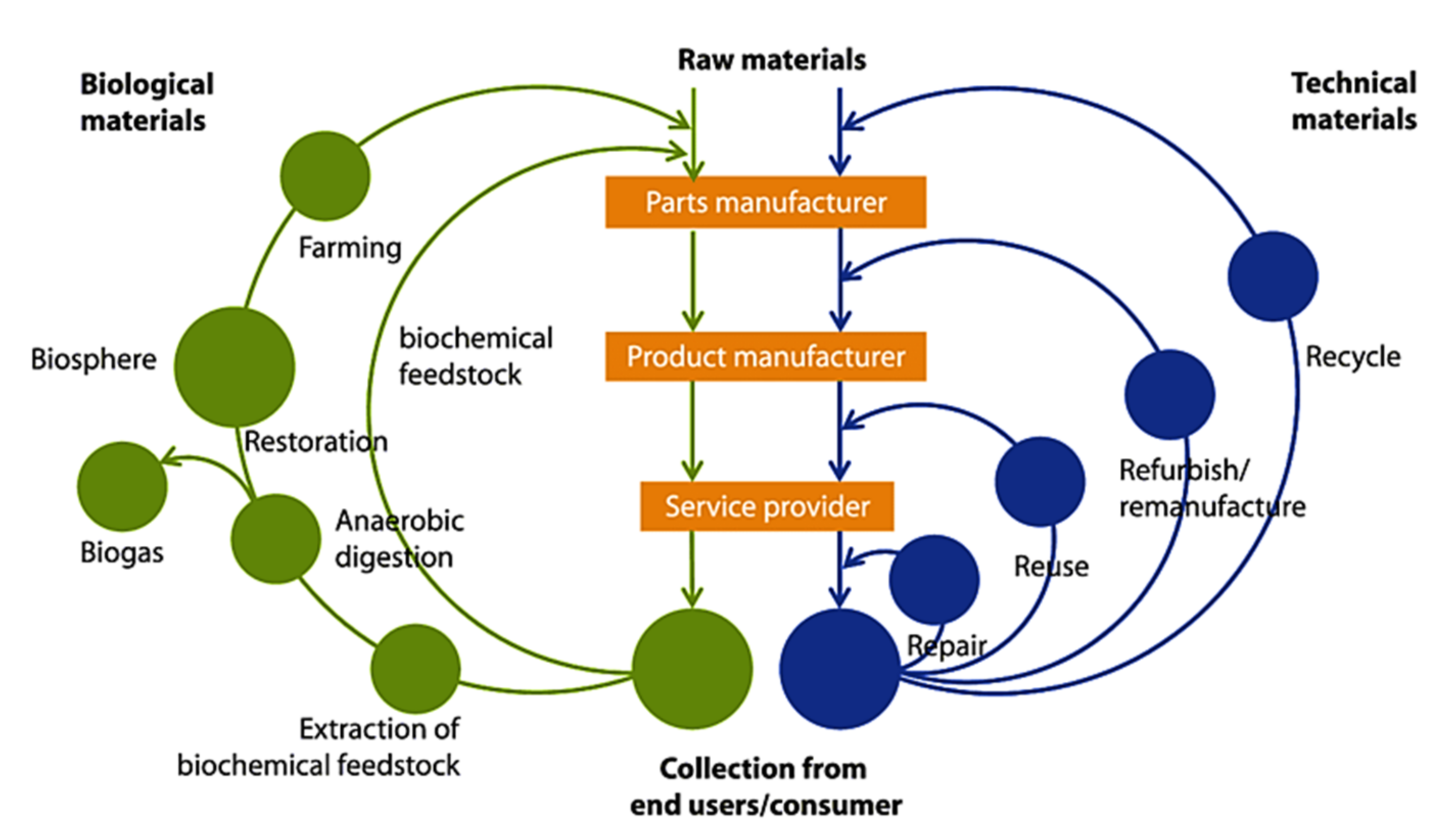

The CE advocates for a more resource-efficient model by decoupling economic growth from the consumption of resources, and it has its origins in the 1970s through the schools of thoughts of the industrial ecology [15], regenerative design [16], the performance economy [17], biomimicry [18], and cradle-to-cradle [19]. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to encouraging the worldwide transition to a CE, has created awareness about the concept. The Foundation created the system or butterfly diagram (Figure 1) based on the idea that material fluxes can be separated into two interconnected loops, namely: the technical and biological material cycles. Composting and anaerobic digestion are examples of how reusable and plant-based elements are used, reproduced, and safely returned to the ecosystem within the biological cycle. The bioeconomy is a developing industry with the capacity to minimize raw material utilization and waste and develop higher-value goods for biological reuse in the long run. Manufactured items are a part of the technological cycle [20].

Figure 1. Circular economy butterfly diagram (adapted from EMF (2013) [20]).

The three principles of the CE model are as follows: (1) protect and develop natural capital by managing limited resources and optimizing renewables streams; (2) maximize resource yields by recirculating high-value products, elements, and resources in both biological and technical processes in all periods; and (3) improve system efficiency by identifying and eliminating adverse effects on the environment [20][21].

Multilateral environmental and development partnerships have changed through the years to emphasize private sector involvement in advancing development and environmental policy objectives. This increased interest in private market mechanisms appears to be based on a changing conception of the government’s legitimate role and new organizational structures for attaining public policy goals and growing the practice in the face of stagnant public funds for multilateral development [22].

The CE would require an integrated approach that coordinates the efforts of all stakeholders in partnership with the business sector to be implemented successfully. According to Agenda 2030, the private sector is a critical stakeholder [23] and plays an important role in achieving the SDGs [24] as it is a key actor in economic development.

References

- WRI (World Resources Institute). Accelerating Building Efficiency: Eight Actions for Urban Leaders. WRI and WRIRoss Center for Sustainable Cities. 2016. Available online: https://www.wri.org/research/accelerating-building-efficiency (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Seto, K.C.S.; Dhakal, A.; Bigio, H.; Blanco, G.C.; Delgado, D.; Dewar, L.; Huang, L.; Inaba, A.; Kansal, A.; Lwasa, S.; et al. Human settlements, infrastructure and spatial planning. In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change; IPCC Working Group III Contribution to AR5; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014.

- World Bank 2020: Urban Development. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview#1 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Delivering the Circular Economy. A Toolkit for Policy Makers. UK. 2015. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/EllenMacArthurFoundation_PolicymakerToolkit.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. The Upcycle: Beyond Sustainability—Designing for Abundance; North Point Press, a Division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- City of Amsterdam. Circular Strategy Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.circle-economy.com/resources/developing-a-roadmap-for-the-first-circular-city-amsterdam. (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- White Paper on the CE of Greater Paris. 2016. Available online: https://api-site.paris.fr/images/77050 (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Peterborough. 2015. Available online: https://www.opportunitypeterborough.co.uk/app/uploads/2011/10/Peterboroughs-energy-environment-sector.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Clemençon, R. Welcome to the Anthropocene: Rio+20 and the meaning of sustainable development. J. Environ. Dev. 2012, 21, 311–338.

- United Nations (UN). The Future We Want. 2012. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/733FutureWeWant.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Pablo, Z.; London, K. Sustainability through Resilient Collaborative Housing Networks: A Case Study of an Australian Pop-Up Shelter. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1271.

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Lefebvre, J.F.; Lanoie, P. Measuring the sustainability of cities: An analysis of the use of local indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 407–418.

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.C. Review of studies on the Critical Success Factors for Public–Private Partnership (PPP) projects from 1990 to 2013. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 1335–1346.

- United Nations (UN). Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development. 2002. Available online: http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/Johannesburg%20Declaration.doc (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Ayres, R.U.; Ayres, L.W. A Handbook of Industrial Ecology; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002.

- Lyle, J.T. Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- Stahel, W.R. The Performance Economy; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2006.

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; William Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1997.

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. 2013. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2022).

- Mendoza, J.M.F.; Sharmina, M.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Heyes, G.; Azapagic, A. Integrating backcasting and eco-design for the CE: The BECE framework. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 526–544.

- Ekins, P.; Domenech, T.; Drummond, P.; Bleischwitz, R.; Hughes, N.; Loti, L. The circular economy: What, Why, How and Where. In Background Paper for an OECD/EC Workshop on 5 July 2019 within the Workshop Series “Managing Environmental and Energy Transitions for Regions and Cities”; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2019.

- Lalaguna, P.D.Y.; Dorodnykh, E. The role of private–public partnerships in the implementation of sustainable development goals: Experience from the SDG Fund. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Filho, W.L., Ed.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 969–982.

- Ridho, T.K.; Vinichenko, M.; Kukushkin, S. Participation of Companies in Emerging Markets to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings; UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta: South Tangerang, Indonesia, 2018; pp. 741–752.

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.6K

Entry Collection:

Environmental Sciences

Revisions:

4 times

(View History)

Update Date:

02 Jun 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No