| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hesham El-Seedi | -- | 9120 | 2022-05-28 12:40:46 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | -6330 word(s) | 2790 | 2022-05-30 03:58:31 | | |

Video Upload Options

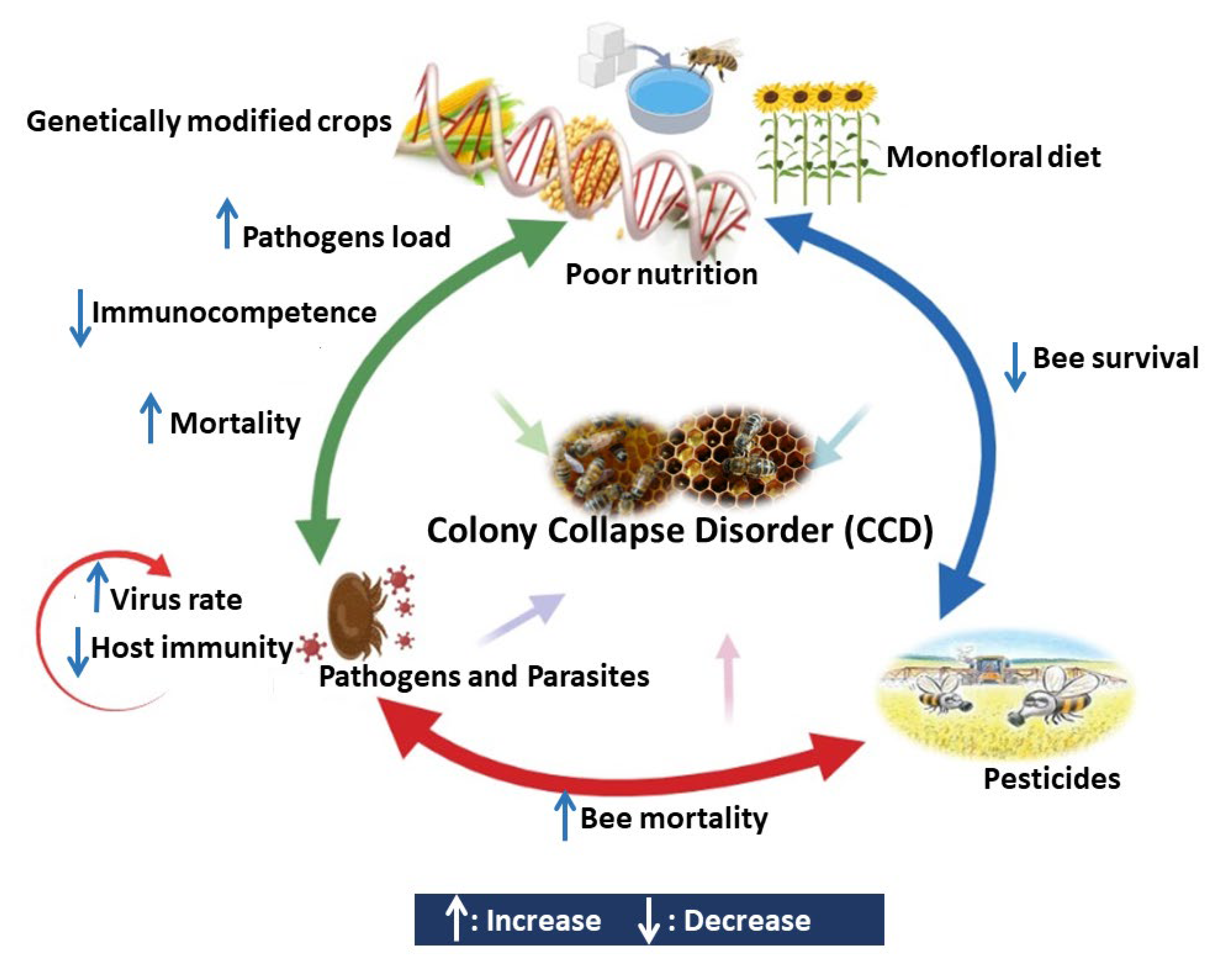

Honeybees are the most prevalent insect pollinator species; they pollinate a wide range of crops. Colony collapse disorder (CCD), which is caused by a variety of biotic and abiotic factors, incurs high economic/ecological loss. Various ecological stressors are microbial infections, exposure to pesticides, loss of habitat, and improper beekeeping practices that are claimed to cause these declines. Honeybees have an innate immune system, which includes physical barriers and cellular and humeral responses to defend against pathogens and parasites. Exposure to various stressors may affect this system and the health of individual bees and colonies.

1. Introduction

2. Honeybee Immunity

3. Main Causes of Honeybee Colony Losses

3.1. Varroa Mite

3.2. Nosema spp.

3.3. Viral Pathogens

3.4. Pesticides

3.5. Malnutrition

3.6. Other Causes

4. Interaction between Different Stressors Affects the Bees Immunocompetence

4.1. Interaction between Pesticides and Pathogens

4.2. Interaction between Pesticides and Poor Nutrition

4.3. Interaction between Pathogens and Poor Nutrition

4.4. Interaction between Parasites and Pathogens

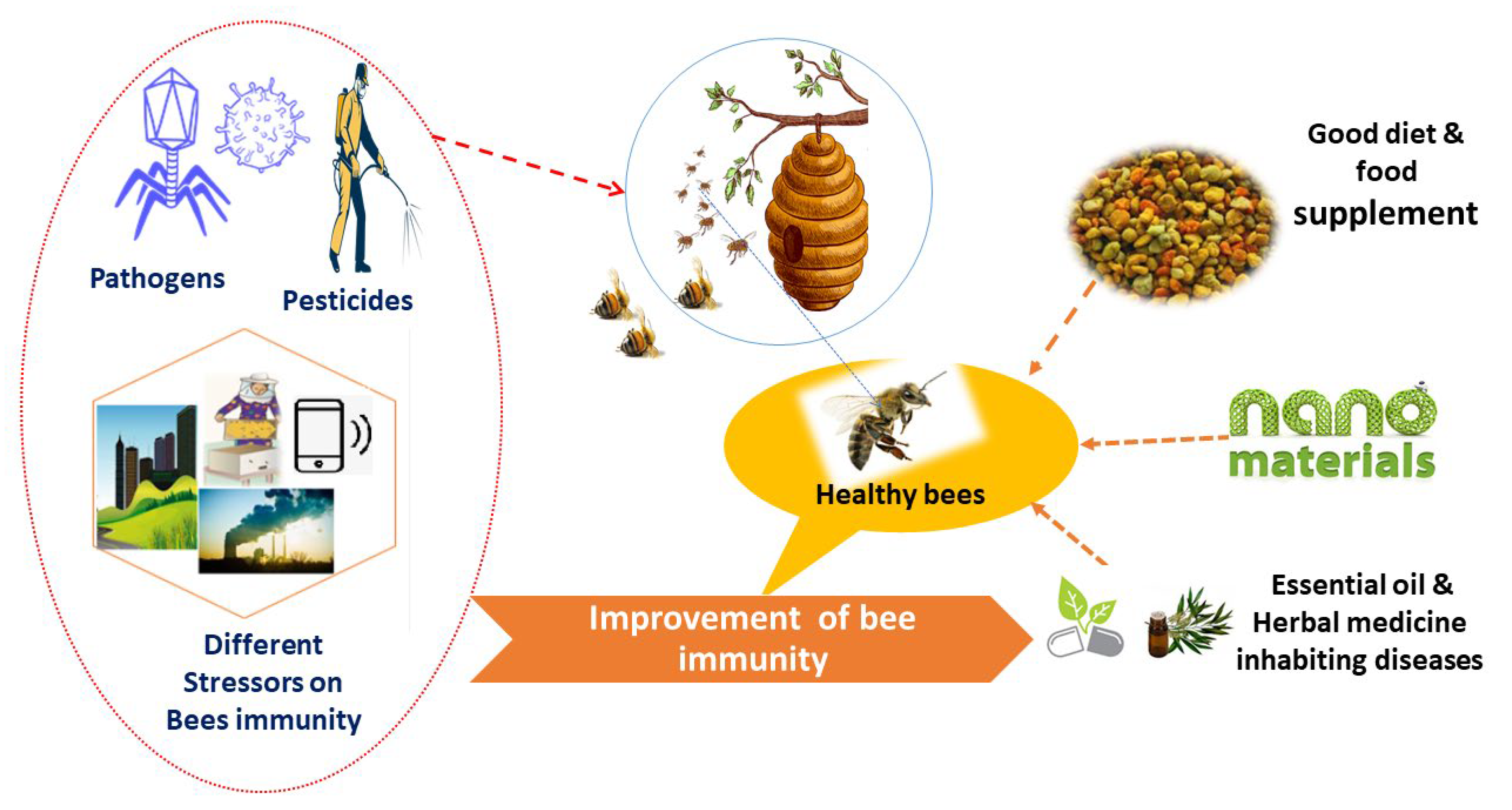

5. Strategies to Enhance Honeybee Immunity

5.1. Fortified Nutrients

5.2. Natural Products as Alternative Sources

Essential oils such as thymol, linalool, and camphor, as well as cocktails of thymol, eucalyptol, menthol, and others, have been confirmed to be particularly efficient in suppressing Varroa mites. These types of essential oils were discovered to lower mortality rates among bees in diseased colonies [72]. Although natural products therapy has fewer side effects than chemical therapy, the efficacy of these substances varies depending on the climate and colony condition [73].

Recently, Chinese herbal medicine has demonstrated a unique antiviral effect for both human and animal life. Honeybees are at risk from SBV and Chinese sacbrood virus (CSBV). Infected larvae will not develop into pupae and will eventually die, and there is currently no effective cure for the virus [19]. Radix isatidis, a Chinese herbal remedy, was primarily utilized to treat human influenza viruses. It has recently been proved to effectively regulate CSBV by suppressing its replication, increasing immunological response, and extending the lifespan of CSBV infection larvae, thereby lowering death rates and preventing CCD [74]. DWV and Lake Sinai virus are two RNA viruses with positive strands that kill honeybees. Bees fed with polypore mushroom extracts exhibited a strong ability to diminish both virus larvae. Modified porphyrins, which are mostly produced by living organisms, can reduce spore burdens in bees and increase the survival likelihood of bees infected with RNA viruses [75].

5.3. Nanomaterials as Novel Alternative Approaches

5.4. Organizations and Initiatives Directed to Saving the Bees

6. Conclusions

References

- Stein, K.; Coulibaly, D.; Stenchly, K.; Goetze, D.; Porembski, S.; Lindner, A.; Konaté, S.; Linsenmair, E.K. Bee pollination increases yield quantity and quality of cash crops in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17691–17700.

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Elshafiey, E.H.; Shetaia, A.A.; El-Wahed, A.A.A.; Algethami, A.F.; Musharraf, S.G.; Alajmi, M.F.; Zhao, C.; Masry, S.H.D.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; et al. Overview of bee pollination and its economic value for crop production. Insects 2021, 12, 688.

- Klein, A.M.; Vaissière, B.E.; Cane, J.H.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Cunningham, S.A.; Kremen, C.; Tscharntke, T. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 274, 303–313.

- Hristov, P.; Neov, B.; Shumkova, R.; Palova, N. Significance of apoidea as main pollinators. Ecological and economic impact and implications for human nutrition. Diversity 2020, 12, 280.

- Dicks, L.V.; Breeze, T.D.; Ngo, H.T.; Senapathi, D.; An, J.; Aizen, M.A.; Basu, P.; Buchori, D.; Galetto, L.; Garibaldi, L.A.; et al. A global-scale expert assessment of drivers and risks associated with pollinator decline. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 5, 1453–1461.

- VanEngelsdorp, D.; Traynor, K.S.; Andree, M.; Lichtenberg, E.M.; Chen, Y.; Saegerman, C.; Cox-Foster, D.L. Colony collapse disorder (CCD) and bee age impact honey bee pathophysiology. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179535.

- van Engelsdorp, D.; Meixner, M.D. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S80–S95.

- Al Naggar, Y.; Baer, B. Consequences of a short time exposure to a sublethal dose of Flupyradifurone (Sivanto) pesticide early in life on survival and immunity in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19753–19762.

- Al Naggar, Y.; Paxton, R.J. Mode of transmission determines the virulence of black queen cell virus in adult honey bees, posing a future threat to bees and apiculture. Viruses 2020, 12, 535.

- Al Naggar, Y.; Paxton, R.J. The novel insecticides flupyradifurone and sulfoxaflor do not act synergistically with viral pathogens in reducing honey bee (Apis mellifera) survival but sulfoxaflor modulates host immunocompetence. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 227–240.

- Jacques, A.; Laurent, M.; Consortium, E.; Ribière-Chabert, M.; Saussac, M.; Bougeard, S.; Budge, G.E.; Hendrikx, P.; Chauzat, M.-P. A pan-European epidemiological study reveals honey bee colony survival depends on beekeeper education and disease control. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172591.

- Mullapudi, E.; Přidal, A.; Pálková, L.; de Miranda, J.R.; Plevka, P. Virion structure of Israeli acute bee paralysis virus. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8150–8159.

- van Engelsdorp, D.; Evans, J.D.; Saegerman, C.; Mullin, C.; Haubruge, E.; Nguyen, B.K.; Frazier, M.; Frazier, J.; Cox-Foster, D.; Chen, Y.; et al. Colony collapse disorder: A descriptive study. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6481.

- Nazzi, F.; Annoscia, D.; Caprio, E.; Di Prisco, G.; Pennacchio, F. Honeybee immunity and colony losses. Entomologia 2014, 2, 80–87.

- Antúnez, K.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Prieto, L.; Meana, A.; Zunino, P.; Higes, M. Immune suppression in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) following infection by Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia). Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2284–2290.

- Fallon, J.P.; Troy, N.; Kavanagh, K. Pre-exposure of Galleria mellonella larvae to different doses of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia causes differential activation of cellular and humoral immune responses. Virulence 2011, 2, 413–421.

- DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Chen, Y. Nutrition, immunity and viral infections in honey bees. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 10, 170–176.

- Karlikow, M.; Goic, B.; Saleh, M.-C. RNAi and antiviral defense in Drosophila: Setting up a systemic immune response. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2014, 42, 85–92.

- Brutscher, L.M.; Flenniken, M.L. RNAi and antiviral defense in the honey bee. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 941897.

- Vung, N.N.; Choi, Y.S.; Kim, I. High resistance to Sacbrood virus disease in Apis cerana (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies selected for superior brood viability and hygienic behavior. Apidologie 2020, 51, 61–74.

- Goblirsch, M.; Warner, J.F.; Sommerfeldt, B.A.; Spivak, M. Social fever or general immune response? Revisiting an example of social immunity in honey bees. Insects 2020, 11, 528.

- Cini, A.; Bordoni, A.; Cappa, F.; Petrocelli, I.; Pitzalis, M.; Iovinella, I.; Dani, F.R.; Turillazzi, S.; Cervo, R. Increased immunocompetence and network centrality of allogroomer workers suggest a link between individual and social immunity in honeybees. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8928–8939.

- Simone, M.; Evans, J.D.; Spivak, M. Resin collection and social immunity in honey bees. Evol. Int. J. Org. Evol. 2009, 63, 3016–3022.

- Borba, R.S.; Spivak, M. Propolis envelope in Apis mellifera colonies supports honey bees against the pathogen, Paenibacillus larvae. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11429–11440.

- Bucekova, M.; Valachova, I.; Kohutova, L.; Prochazka, E.; Klaudiny, J.; Majtan, J. Honeybee glucose oxidase—its expression in honeybee workers and comparative analyses of its content and H2O2-mediated antibacterial activity in natural honeys. Naturwissenschaften 2014, 101, 661–670.

- Brudzynski, K. Effect of hydrogen peroxide on antibacterial activities of Canadian honeys. Can. J. Microbiol. 2006, 52, 1228–1237.

- Gebremedhn, H.; Amssalu, B.; De Smet, L.; De Graaf, D.C. Factors restraining the population growth of Varroa destructor in Ethiopian honey bees (Apis mellifera simensis). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223236.

- Ramsey, S.D.; Ochoa, R.; Bauchan, G.; Gulbronson, C.; Mowery, J.D.; Cohen, A.; Lim, D.; Joklik, J.; Cicero, J.M.; Ellis, J.D.; et al. Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honey bee fat body tissue and not hemolymph. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1792–1801.

- Richards, E.H.; Jones, B.; Bowman, A. Salivary secretions from the honeybee mite, Varroa destructor: Effects on insect haemocytes and preliminary biochemical characterization. Parasitology 2011, 138, 602–608.

- Koleoglu, G.; Goodwin, P.H.; Reyes-Quintana, M.; Guzman-Novoa, E. Effect of Varroa destructor, counding and Varroa homogenate on gene expression in brood and adult honey bees. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169669.

- Nazzi, F.; Brown, S.P.; Annoscia, D.; Del Piccolo, F.; Di Prisco, G.; Varricchio, P.; Della Vedova, G.; Cattonaro, F.; Caprio, E.; Pennacchio, F. Synergistic parasite-pathogen interactions mediated by host immunity can drive the collapse of honeybee colonies. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002735.

- Kielmanowicz, M.G.; Inberg, A.; Lerner, I.M.; Golani, Y.; Brown, N.; Turner, C.L.; Hayes, G.J.R.; Ballam, J.M. Prospective large-scale field study generates predictive model identifying major contributors to colony losses. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004816.

- Di Prisco, G.; Pennacchio, F.; Caprio, E.; Boncristiani, H.F.; Evans, J.D.; Chen, Y. Varroa destructor is an effective vector of Israeli acute paralysis virus in the honeybee, Apis mellifera. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 151–155.

- Dainat, B.; Evans, J.D.; Chen, Y.P.; Gauthier, L.; Neumann, P. Predictive markers of honey bee colony collapse. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32151.

- Gisder, S.; Schüler, V.; Horchler, L.L.; Groth, D.; Genersch, E. Long-term temporal trends of Nosema spp. infection prevalence in Northeast Germany: Continuous spread of Nosema ceranae, an emerging pathogen of honey bees (Apis mellifera), but no general replacement of Nosema apis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 301–314.

- Higes, M.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Botías, C.; Bailón, E.G.; González-Porto, A.V.; Barrios, L.; Del Nozal, M.J.; Bernal, J.L.; Jiménez, J.J.; Palencia, P.G.; et al. How natural infection by Nosema ceranae causes honeybee colony collapse. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 10, 2659–2669.

- Dosselli, R.; Grassl, J.; Carson, A.; Simmons, L.W.; Baer, B. Flight behaviour of honey bee (Apis mellifera) workers is altered by initial infections of the fungal parasite Nosema apis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36649–36659.

- Grozinger, C.M.; Flenniken, M.L. Bee viruses: Ecology, pathogenicity, and impacts. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2019, 64, 205–226.

- Škubnik, K.; Nováček, J.; Füzik, T.; Přidal, A.; Paxton, R.J.; Plevka, P. Structure of deformed wing virus, a major honey bee pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 3210–3215.

- Mao, W.; Schuler, M.A.; Berenbaum, M.R. Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8842–8846.

- Alaux, C.; Kemper, N.; Kretzschmar, A.; Le Conte, Y. Brain, physiological and behavioral modulation induced by immune stimulation in honeybees (Apis mellifera): A potential mediator of social immunity? Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 1057–1060.

- Brodschneider, R.; Crailsheim, K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie 2010, 41, 278–294.

- Cotter, S.C.; Simpson, S.J.; Raubenheimer, D.; Wilson, K. Macronutrient balance mediates trade-offs between immune function and life history traits. Funct. Ecol. 2011, 25, 186–198.

- Frizzera, D.; Del Fabbro, S.; Ortis, G.; Zanni, V.; Bortolomeazzi, R.; Nazzi, F.; Annoscia, D. Possible side effects of sugar supplementary nutrition on honey bee health. Apidologie 2020, 51, 594–608.

- Aldgini, H.M.M.; Al-Abbadi, A.A.; Abu-Nameh, E.S.M.; Alghazeer, R.O. Determination of metals as bio indicators in some selected bee pollen samples from Jordan. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 1418–1422.

- Nikolić, T.V.; Kojić, D.; Orčić, S.; Batinić, D.; Vukašinović, E.; Blagojević, D.P.; Purać, J. The impact of sublethal concentrations of Cu, Pb and Cd on honey bee redox status, superoxide dismutase and catalase in laboratory conditions. Chemosphere 2016, 164, 98–105.

- Fisogni, A.; Hautekèete, N.; Piquot, Y.; Brun, M.; Vanappelghem, C.; Michez, D.; Massol, F. Urbanization drives an early spring for plants but not for pollinators. Oikos 2020, 129, 1681–1691.

- Sadowska, M.; Gogolewska, H.; Pawelec, N.; Sentkowska, A.; Krasnodębska-Ostręga, B. Comparison of the contents of selected elements and pesticides in honey bees with regard to their habitat. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 371–380.

- Appler, R.H.; Frank, S.D.; Tarpy, D.R. Within-colony variation in the immunocompetency of managed and feral honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) in different urban landscapes. Insects 2015, 6, 912–925.

- Dabour, K.; Al Naggar, Y.; Masry, S.; Naiem, E.; Giesy, J.P. Cellular alterations in midgut cells of honey bee workers (Apis millefera L.) exposed to sublethal concentrations of CdO or PbO nanoparticles or their binary mixture. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 1356–1367.

- AL Naggar, Y.; Dabour, K.; Masry, S.; Sadek, A.; Naiem, E.; Giesy, J.P. Sublethal effects of chronic exposure to CdO or PbO nanoparticles or their binary mixture on the honey bee (Apis millefera L.). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 19004–19015.

- Sharma, V.P.; Kumar, N.R. Changes in honeybee behaviour and biology under the influence of cellphone radiations. Curr. Sci. 2010, 98, 1376–1378.

- Santhosh Kumar, S. Colony collapse disorder (CCD) in honey bees caused by EMF radiation. Bioinformation 2018, 14, 521–524.

- Lupi, D.; Tremolada, P.; Colombo, M.; Giacchini, R.; Benocci, R.; Parenti, P.; Parolini, M.; Zambon, G.; Vighi, M. Effects of pesticides and electromagnetic fields on honeybees: A field study using biomarkers. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2020, 14, 107–122.

- Odemer, R.; Odemer, F. Effects of radiofrequency electromagnetic radiation (RF-EMF) on honey bee queen development and mating success. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 661, 553–562.

- O’Neal, S.T.; Anderson, T.D.; Wu-Smart, J.Y. Interactions between pesticides and pathogen susceptibility in honey bees. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 26, 57–62.

- Pettis, J.S.; Vanengelsdorp, D.; Johnson, J.; Dively, G. Pesticide exposure in honey bees results in increased levels of the gut pathogen Nosema. Naturwissenschaften 2012, 99, 153–158.

- Di, G.; Cavaliere, V.; Annoscia, D.; Varricchio, P.; Caprio, E.; Nazzi, F. Neonicotinoid clothianidin adversely affects insect immunity and promotes replication of a viral pathogen in honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18466–18471.

- Dussaubat, C.; Maisonnasse, A.; Crauser, D.; Tchamitchian, S.; Bonnet, M.; Cousin, M.; Kretzschmar, A.; Brunet, J.-L.; Le Conte, Y. Combined neonicotinoid pesticide and parasite stress alter honeybee queens’ physiology and survival. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31430–31436.

- Aufauvre, J.; Misme-Aucouturier, B.; Viguès, B.; Texier, C.; Delbac, F.; Blot, N. Transcriptome analyses of the honeybee response to Nosema ceranae and insecticides. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91686.

- Retschnig, G.; Neumann, P.; Williams, G.R. Thiacloprid-Nosema ceranae interactions in honey bees: Host survivorship but not parasite reproduction is dependent on pesticide dose. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 118, 18–19.

- Tosi, S.; Nieh, J.C.; Sgolastra, F.; Cabbri, R.; Medrzycki, P. Neonicotinoid pesticides and nutritional stress synergistically reduce survival in honey bees. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 284, 20171711–20171719.

- Sánchez-bayo, F.; Goulson, D.; Pennacchio, F.; Nazzi, F.; Goka, K.; Desneux, N. Are bee diseases linked to pesticides ?—A brief review. Environ. Int. 2016, 89–90, 7–11.

- Wu-Smart, J.; Spivak, M. Sub-lethal effects of dietary neonicotinoid insecticide exposure on honey bee queen fecundity and colony development. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32108–32119.

- Foley, K.; Fazio, G.; Jensen, A.B.; Hughes, W.O.H. Nutritional limitation and resistance to opportunistic Aspergillus parasites in honey bee larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 111, 68–73.

- Koch, H.; Brown, M.J.; Stevenson, P.C. The role of disease in bee foraging ecology. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017, 21, 60–67.

- Dolezal, A.G.; Carrillo-Tripp, J.; Judd, T.M.; Allen Miller, W.; Bonning, B.C.; Toth, A.L. Interacting stressors matter: Diet quality and virus infection in honeybee health. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 181803–181813.

- Dolezal, A.G.; Toth, A.L. Feedbacks between nutrition and disease in honey bee health. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2018, 26, 114–119.

- Zhao, Y.; Heerman, M.; Peng, W.; Evans, J.D.; Rose, R.; DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Simone-Finstrom, M.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Cook, S.C. The dynamics of deformed wing virus concentration and host defensive gene expression after Varroa mite parasitism in honey bees, Apis mellifera. Insects 2019, 10, 16.

- Hou, C.; Rivkin, H.; Slabezki, Y.; Chejanovsky, N. Dynamics of the presence of israeli acute paralysis virus in honey bee colonies with colony collapse disorder. Viruses 2014, 6, 2012–2027.

- Sperandio, G.; Simonetto, A.; Carnesecchi, E.; Costa, C.; Hatjina, F.; Tosi, S.; Gilioli, G. Beekeeping and honey bee colony health: A review and conceptualization of beekeeping management practices implemented in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133795–133806.

- Adamczyk, S.; Lázaro, R.; Pérez-Arquillué, C.; Conchello, P.; Herrera, A. Evaluation of residues of essential oil components in honey after different anti-Varroa treatments. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 10085–10090.

- Rosenkranz, P.; Aumeier, P.; Ziegelmann, B. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2010, 103, S96–S119.

- Sun, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, S.; Hou, C.; Xu, J.; Zhao, D.; Chen, Y. Antiviral activities of a medicinal plant extract against sacbrood virus in honeybees. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 83–92.

- Tauber, J.P.; Collins, W.R.; Schwarz, R.S.; Chen, Y.; Grubbs, K.; Huang, Q.; Lopez, D.; Peterson, R.; Evans, J.D. Natural product medicines for honey bees: Perspective and protocols. Insects 2019, 10, 356.

- Hasan, S. A review on nanoparticles: Their synthesis and types. Res. J. Recent Sci 2015, 2277, 2502–2504.

- Sousa, F.; Ferreira, D.; Reis, S.; Costa, P. Current insights on antifungal therapy: Novel nanotechnology approaches for drug delivery systems and new drugs from natural sources. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 248.

- Culha, M.; Kalay, Ş.; Sevim, E.; Pinarbaş, M.; Baş, Y.; Akpinar, R.; Karaoğlu, Ş.A. Biocidal properties of maltose reduced silver nanoparticles against American foulbrood diseases pathogens. Biometals 2017, 30, 893–902.

- Potts, S.G.; Roberts, S.P.M.; Dean, R.; Marris, G.; Brown, M.A.; Jones, R.; Neumann, P.; Settele, J. Declines of managed honey bees and beekeepers in Europe. J. Apic. Res. 2010, 49, 15–22.