Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zhonggen Yu | -- | 1920 | 2022-05-27 11:44:36 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -11 word(s) | 1909 | 2022-05-27 11:56:03 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Yu, Z.; Zhang, K. Gamified English Vocabulary Applications. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23489 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Yu Z, Zhang K. Gamified English Vocabulary Applications. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23489. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Yu, Zhonggen, K.x Zhang. "Gamified English Vocabulary Applications" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23489 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Yu, Z., & Zhang, K. (2022, May 27). Gamified English Vocabulary Applications. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23489

Yu, Zhonggen and K.x Zhang. "Gamified English Vocabulary Applications." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

Learning vocabulary through mobile applications has gained momentum in recent years. The use of smart mobile devices was getting increasingly widespread as the mobile Internet develops at a rapid pace, and numerous English vocabulary learning applications were developed to help learners expand their English vocabulary through mobile learning. English vocabulary learning apps were generally incorporated with gamification to assist users in acquiring and recollecting new vocabulary. Time constraints, rewards, feedback, characters, and challenges were all universal game components in vocabulary learning applications, allowing the process to be enjoyable and game-like.

gamified vocabulary apps

UTAUT

1. Introduction

Vocabulary learning apps with gamified features could improve learning outcomes [1]. Gamified vocabulary learning apps greatly enhanced the English vocabulary learning outcomes of lower achievers [2]. University EFL learners who learned words via the mobile-assisted gamification learning method outperformed those who did not, and they also fostered enjoyment and motivation [3]. Games in vocabulary learning apps motivated non-English majors to learn vocabulary and helped them form learning habits [1]. A quasi-experiment comparing the impact of game-based vocabulary learning apps with traditional paper-based vocabulary list learning found that game-based vocabulary learning apps were beneficial to students in terms of vocabulary achievement, motivation, and self-confidence [4].

2. Gamified English Vocabulary APPs

It is of great necessity to firstly define gamification in English vocabulary applications. As Yang et al. put forward, gamification was referred to as transforming non-game contexts, e.g., language acquisition, into games [5]. More specifically, gamification was defined by a wide consensus as to the adoption of game features and mechanics in non-game settings [6]. In other words, the gamified contexts in vocabulary learning not only included all kinds of games presented through various multimedia inputs such as text, image, audio, and video [7] but also key game components. Users could experience vocabulary learning through digital games or video games [3][8]. There could also exist universal game components in vocabulary learning applications such as time constraints, rewards, feedback, characters, and challenges [7]. For instance, many Chinese learners preferred learning new English words via an app called BaiCiZhan. In one of the quiz modes, users could choose the correct picture according to the given word and gain scores.

Many studies applied gamified vocabulary apps to testify to their usefulness as the gamified English vocabulary apps developed rapidly. One of the important reasons was that in comparison to other English skills, English vocabulary learning required a considerable amount of information to be learned and recalled, and featured “memory fragmentation and easy to forget” [9]. In this regard, some studies proved effective in improving English vocabulary learning outcomes, enjoyment, and motivation using gamified vocabulary apps [3]. It was also worth mentioning that when gamified vocabulary applications were employed, elements such as self-regulated learning and psychological processes could have a significant impact on English vocabulary learning [10][11].

Insufficient studies have ever investigated what may result in the use of gamified vocabulary applications. Despite the investigation into the effectiveness of gamified vocabulary applications, few studies have probed into the factors that could influence users’ behavior in the use of those apps. Although gamification had beneficial impacts, the results were also highly reliant on individuals who utilized it, and the context where gamification was used [12]. The UTAUT model to explore learners’ acceptance and use of gamified English vocabulary apps are adopted.

3. UTAUT in Gamified English Vocabulary Learning

Venkatesh, Morris, and Davis proposed the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) in 2003, which was an integration of eight technology acceptance models [13]. The synthesized eight theories and models included the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), the Motivational Model (MM), the Model of PC Utilization (MPCU), Innovation Diffusion Theory (IDT), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), a combined Theory of Planned Behavior/Technology Acceptance Model (C-TPB-TAM), and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [14]. Venkatesh et al. also found that UTAUT outperformed every single individual model with an adjusted R2 of 69%.

Few researches of gamified vocabulary apps utilized UTAUT. The UTAUT was mainly implemented in organizational settings [15] and was only introduced to mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) in recent years, not to mention its use in gamified vocabulary learning. There were several attempts to study MALL utilizing the UTAUT [13][16][17][18][19][20]. The findings offered implications for the adoption of the UTAUT as an appropriate model for investigating MALL acceptance [21], which was empirically confirmed as having greater explanatory power over other single technology acceptance models [22]. Since learning with gamified vocabulary apps belonged to MALL, the UTAUT model may be used to examine the acceptance and use of gamified vocabulary apps as well.

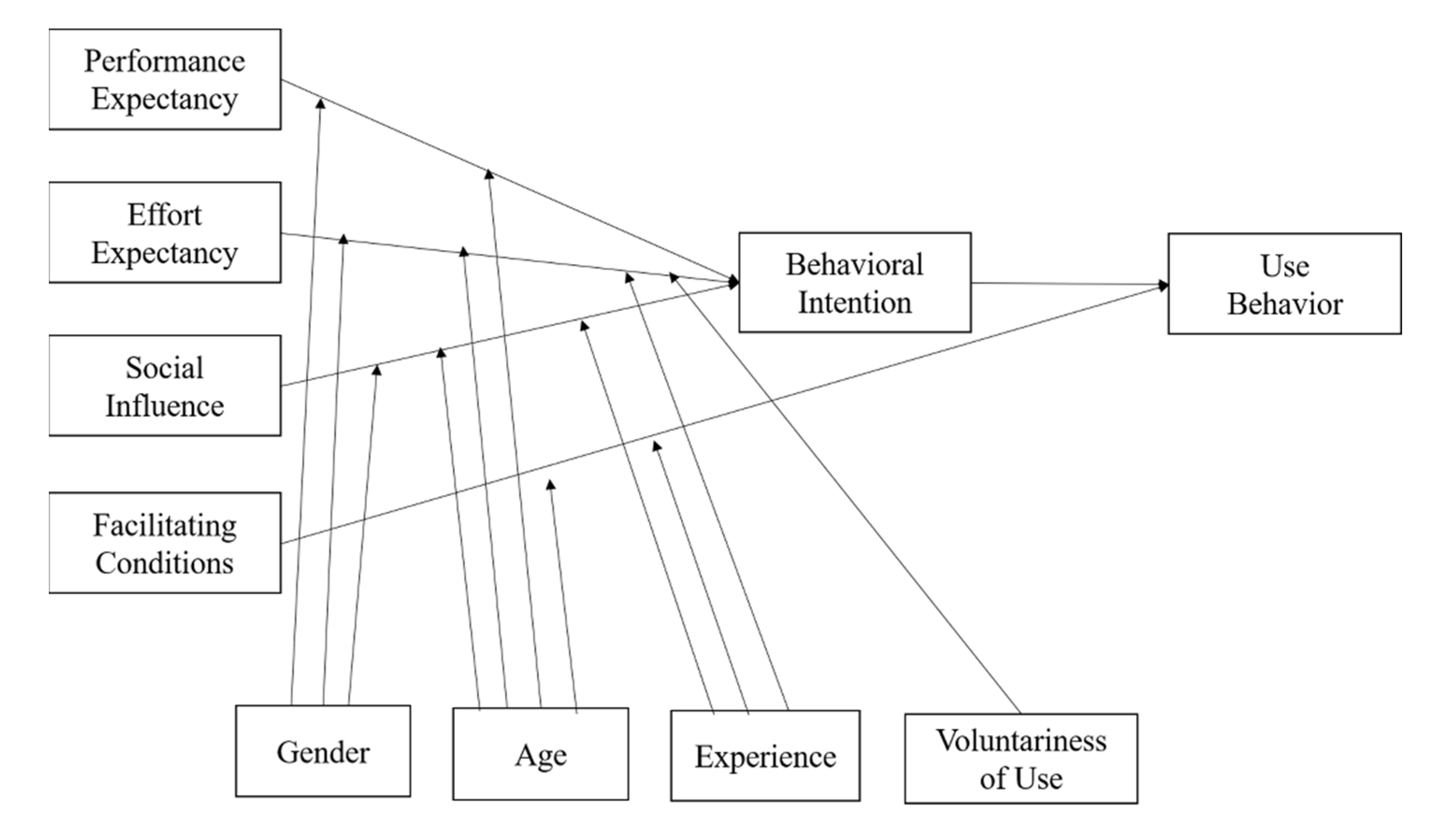

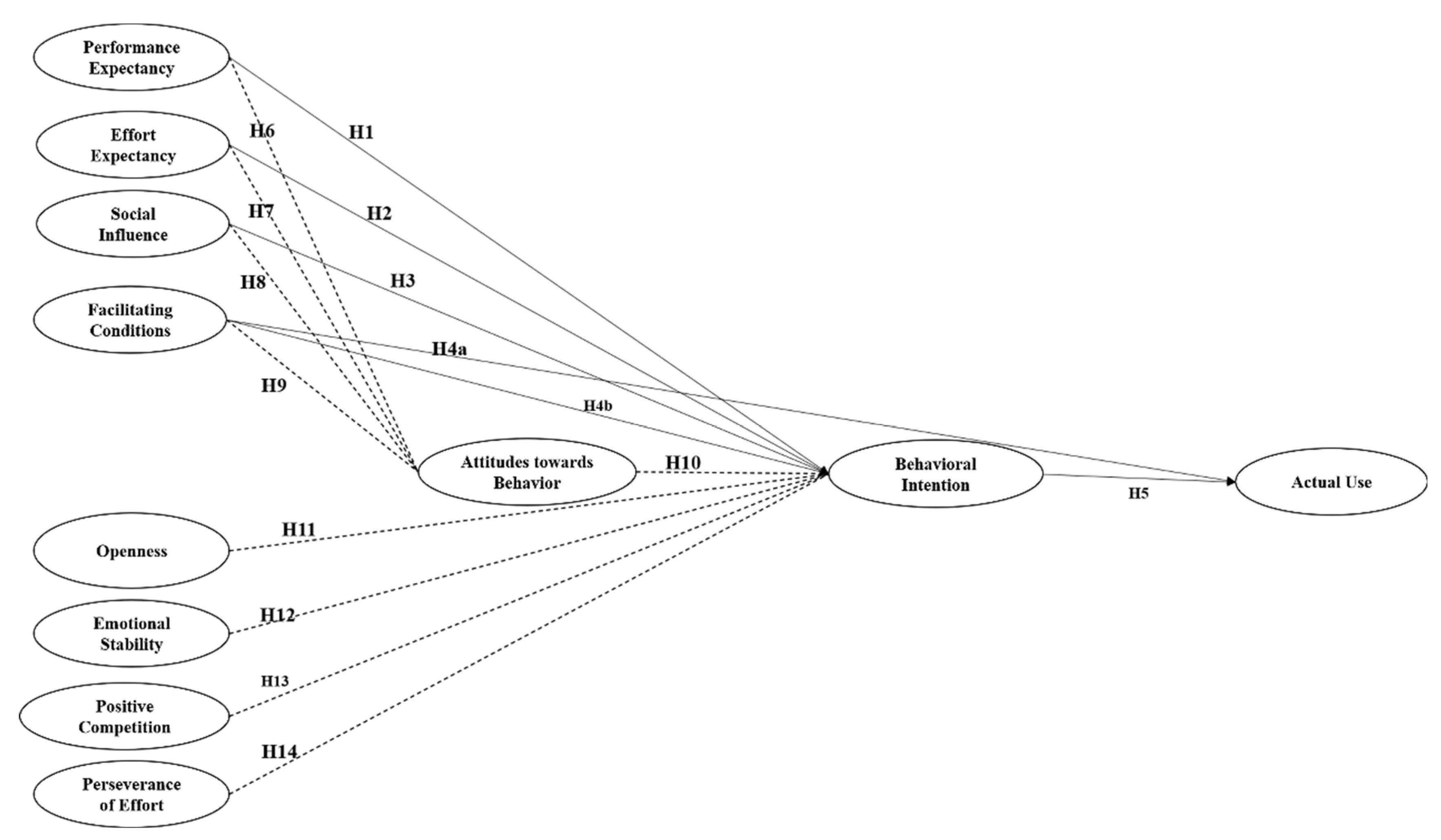

Although the UTAUT model had fixed constructs, researchers could also extend it by including new ones. Performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI), and facilitating conditions (FC) were the four main determinants of users’ intention to utilize technology and actual use in the UTAUT [23]. Moreover, gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of use were taken into account to moderate users’ individual differences in their technology acceptance. Most studies extended the original UTAUT by including other relevant factors according to specific research purposes and targets, e.g., student-centric learning [16], teacher feedback and compatibility [20], and management learning [23]. This research extended the UTAUT initially proposed by Venkatesh et al. by including attitudes towards behavior (ATB), openness (OP), emotional stability (ES), positive competition (PC), and perseverance of effort (POE). The reason why the authors included some of the personality factors was that personalities could influence users’ intention and the actual behavior in using a certain system (e.g., people with a high level of openness were willing to try out new things and experiences, and they could be likely to have strong intention to use a gamified vocabulary application).

Figure 1 presents the original model. Performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence affect behavior intention, while behavior intention and facilitating conditions have a direct impact on use behavior. Gender, age, experience, and voluntariness of use are four moderators with gender moderating PE, EE, and SI, and experience moderating EE, SI, and FC. Age moderates all of the four core exogenous constructs while voluntariness of use only moderates EE.

Figure 1. The UTAUT model.

As shown in Figure 2, demonstrating the implementation of gamified English vocabulary apps and the hypothesized relationships.

Figure 2. The proposed UTAUT model with new constructs.

3.1. Performance Expectancy

According to Venkatesh et al., performance expectancy indicated the degree to which an individual felt that employing an information system would assist him or her in achieving gains in work productivity [24]. In the context of mobile-assisted language learning, performance expectancy was of great significance in affecting learners’ behavioral intention of using certain mobile systems [16][18][20][21].

3.2. Effort Expectancy

Effort expectancy in UTAUT referred to the expected degree of ease using a particular system, which was derived from Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [25]. In many studies of mobile-assisted language learning (MALL), EE correlated with BI [23][26][27]. However, some studies found contradictory results with EE neither influencing BI nor being a significant predictor of BI [28][29]. Therefore, it was meaningful to examine whether EE could determine BI in gamified English vocabulary apps.

3.3. Social Influence

Social influence was defined as the degree that an individual was influenced to use a system by his or her important others [15]. Although plenty of empirical studies confirmed the significant correlation between SI and BI [23][26][29][30], some cases revealed that the two variables were not necessarily related to each other [27]. This research thus planned to further investigate this pair of relationship in gamified vocabulary applications.

3.4. Facilitating Conditions

The definition of facilitating conditions was the degree to which a person felt that organizational and technological infrastructure existed to facilitate system utilization [25]. Some researchers found FC not correlated with BI in MALL [28][29] while others offered the opposite outcome [23]. In addition, FC also had an impact on AU [31][32].

3.5. Behavioral Intention

Behavioral intention was operationally defined, as users’ intention and motivation to utilize a certain gamified vocabulary application. Behavioral intention was positively related to use behavior in theory [13]. Moreover, this correlation was also confirmed in numerous empirical studies on MALL and online learning [31][32].

3.6. Attitudes towards Behavior

ATB was an important construct in UTAUT. Although not included in the UTAUT, the attitudes construct was found to be an essential and appropriate element in information technology and information system (IT/IS) [16] as well as in education [13]. It was proved that ATB affected BI [26][28], and some studies even revealed that ATB was the only factor influencing BI [31]. Besides, ATB was also related to PE [31], SI [26][31], EE [26], and FC [13]. In this light, it was necessary to study the relationship between ATB and the other five mentioned elements in the gamified vocabulary learning context.

3.7. Openness

Openness was one of the Big Five Personality Traits which connected to intellectual curiosity [33]. People who possessed the openness personality trait were eager to try new things and experiences. Accordingly, those with openness may be willing and intended to use technology to facilitate their study in the context of technology-assisted language learning. More specifically, it is possible that openness can be a predictor of the intention to use gamified vocabulary apps.

Openness could predict users’ intentions. Marinescu & Nicolae found that students demonstrated their openness to adopting computer-assisted language learning in a formal context [34]. In addition, openness exerted an indirect positive influence on teachers’ behavioral intention to use tablet PC in their teaching activities [35]. Moreover, openness could also indirectly affect students’ opinions and intentions to have LMOOCs (online language courses) [36].

Nevertheless, not all studies revealed the positive influence of openness on users’ intentions. In the healthcare area, personal traits such as openness were not relevant predictors for the perceived usefulness of a health device which could be predicted by behavioral intention [37]. Besides, Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham found contradictory results in their research with openness negatively correlated with one of the learning measures [38]. Such a finding has offered researchers a perspective that openness may not always be a positive predictor.

3.8. Emotional Stability

Emotional stability, as an important personal quality, referred to an individual’s proclivity to be emotionally adaptable [39]. To some degree, emotional stability had a great impact on the prediction of behavior [40]. Emotionally stable individuals could be expected to be calm, undisturbed, and to complain little about their personal problems and concerns, making high emotional stability a good personality feature [41].

3.9. Positive Competition

Game-based learning was usually integrated with competition [42]. Students may benefit from competition-based learning in enhancing their engagement, learning performance, creativity, as well as their learning motivation [42][43]. On the contrary, some researchers also pointed out that increased anxiety, poor work performance, loss of interpersonal ties, and erosion of learning responsibility were all negative outcomes of competition [44]. In some cases, particularly when external incentives were offered to students, competition in learning might reduce students’ sense of control, resulting in low intrinsic motivation [43].

3.10. Perseverance of Effort

Perseverance of effort (POE), or just perseverance, was considered a beneficial personality for an individual. It was defined as one’s inclination to work hard even in the face of adversity [45]. In other words, people with a high level of perseverance were predicted to be more likely to achieve their long-term goals.

Perseverance might be a predictor of the intention of using gamified vocabulary apps. Regardless of the fact that perseverance was more frequently addressed as an outcome than as a predictor, psychologists in the first half of the twentieth century were particularly interested in the study of perseverance as a predictor, particularly as a stable individual difference [46]. In the gamified vocabulary learning setting, POE was possible to influence users’ intention and behavior in learning vocabulary through mobile apps since vocabulary learning could be a long-time process that also requires people’s patience and determination.

References

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Y. Perceptions of Non-English Major College Students on Learning English Vocabulary with Gamified Apps. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2021, 16, 268–276.

- Waluyo, B.; Bucol, J.L. The Impact of Gamified Vocabulary Learning Using Quizlet on Low-Proficiency Students. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J. 2021, 22, 164–185.

- Fithriani, R. The Utilization of Mobile-Assisted Gamification for Vocabulary Learning: Its Efficacy and Perceived Benefits. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J. 2021, 22, 146–163.

- Li, R. Does Game-Based Vocabulary Learning APP Influence Chinese EFL Learners’ Vocabulary Achievement, Motivation, and Self-Confidence? SAGE Open. 2021, 11, 21582440211003092.

- Yang, F.-C.O.; Wu, W.-C.V.; Wu, Y.-J.A. Using a Game-Based Mobile App to Enhance Vocabulary Acquisition for English Language Learners. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 2020, 18, 24.

- Seaborn, K.; Fels, D.I. Gamification in Theory and Action: A Survey. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2015, 74, 14–31.

- Wang, F.L.; Zhang, R.; Zou, D.; Au, O.T.S.; Xie, H.; Wong, L.P. A Review of Vocabulary Learning Applications: From the Aspects of Cognitive Approaches, Multimedia Input, Learning Materials and Game Elements. Knowl. Manag. E-Learn. Int. J. 2021, 13, 250–272.

- Tamtama, G.I.W.; Suryanto, P.; Suyoto, S. Design of English Vocabulary Mobile Apps Using Gamification: An Indonesian Case Study for Kindergarten. Int. J. Eng. Pedagog. 2020, 10, 150–162.

- Chen, T.; Peng, L.; Yang, J.; Cong, G. Analysis of User Needs on Downloading Behavior of English Vocabulary APPs Based on Data Mining for Online Comments. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1341.

- Chen, C.-M.; Chen, L.-C.; Yang, S.-M. An English Vocabulary Learning App with Self-Regulated Learning Mechanism to Improve Learning Performance and Motivation. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2019, 32, 237–260.

- Dindar, M.; Ren, L.; Järvenoja, H. An Experimental Study on the Effects of Gamified Cooperation and Competition on English Vocabulary Learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 52, 142–159.

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does Gamification Work?—A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; Sprague, R.H., Ed.; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3025–3034.

- Garcia, A.; Vidal, E. Mobile-Learning Experience as Support for Improving the Capabilities of the English Area for Engineering Students. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Virtual Reality and Visualization (ICVRV), Hong Kong, China, 18–19 November 2019; Wang, D., Cadavid, A.N., Liu, Y., Xu, M., Eds.; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 202–204.

- Williams, M.D.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT): A Literature Review. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2015, 28, 443–488.

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Tamilmani, K.; Raman, R. A Meta-Analysis Based Modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (Meta-UTAUT): A Review of Emerging Literature. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 13–18.

- Bere, A. Exploring Determinants for Mobile Learning User Acceptance and Use: An Application of UTAUT. In Proceedings of the 2014 11th International Conference on Information Technology: New Generations, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 7–9 April 2014; IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2014; pp. 84–90.

- Duman, G.; Orhon, G.; Gedik, N. Research Trends in Mobile Assisted Language Learning from 2000 to 2012. ReCALL 2015, 27, 197–216.

- Ho, C.T.B.; Chou, Y.T.; O’Neill, P. Technology Adoption of Mobile Learning: A Study of Podcasting. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2010, 8, 468.

- Ho, C.-T.B.; Chou, Y.-T.T. The Critical Factors for Applying Podcast in Mobile Language Learning. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Information Management and Engineering, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3–5 April 2009; IEEE: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2009; pp. 411–415.

- Morchid, N. The Determinants of Use and Acceptance of Mobile Assisted Language Learning: The Case of EFL Students in Morocco. Arab World Engl. J. 2019, 5, 76–97.

- Hoi, V.N. Understanding Higher Education Learners’ Acceptance and Use of Mobile Devices for Language Learning: A Rasch-Based Path Modeling Approach. Comput. Educ. 2020, 146, 103761.

- Luo, Y. An Investigation of University Students’ Perceptions and Acceptance of Mobile Technology Use in Learning English as a Second Language in China-Web of Science Core Collection. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000553304902115 (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Mekhzoumi, O.; Hamzah, M.H.; Krishnasamy, H.N. Determinants of Mobile Applications Acceptance for English Language Learning in Universiti Utara Malaysia. J. Adv. Res. Des. 2018, 51, 1–13.

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478.

- Chang, A. UTAUT and UTAUT 2: A Review and Agenda for Future Research. Winners 2012, 13, 10–114.

- Embi, M.A. Factors Influencing Polytechnic English as Second Language (ESL) Learners’ Attitude and Intention for Using Mobile Learning. Asian ESP J. 2018, 14, 195–208.

- Esfandiari, R.; Sokhanvar, F. Modified Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology in Investigating Iranian Language Learners’ Attitudes toward Mobile Assisted Language Learning (MALL). Interdiscip. J. Virtual Learn. Med Sci. 2016, 6, 93–105.

- Hoang, Q.; Pham, T.; Dang, Q.; Nguyen, T. Factors Influencing Vietnamese Teenagers’ Intention to Use Mobile Devices for English Language Learning. In Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference of the Asia Association of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (AsiaCALL-2-2021), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 26–27 November 2021; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 230–245.

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.; Fang, S. Factors Affecting Macau Undergraduate Students’ Acceptance of Hospitality English App: Applicability of UTAUT Model. Int. J. Innov. Learn. 2021, 29, 250–266.

- Kaur, D.J.; Saraswat, N.; Alvi, I. Exploring the Effects of Blended Learning Using WhatsApp on Language Learners’ Lexical Competence. Rupkatha J. Interdiscip. Stud. Humanit. 2021, 13, 1–7.

- Altalhi, M. Toward a Model for Acceptance of MOOCs in Higher Education: The Modified UTAUT Model for Saudi Arabia. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 1589–1605.

- Hu, S.; Laxman, K.; Lee, K. Exploring Factors Affecting Academics’ Adoption of Emerging Mobile Technologies-an Extended UTAUT Perspective. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 4615–4635.

- Kang, H.; Kusuma, G.P. The Effectiveness of Personality-Based Gamification Model for Foreign Vocabulary Online Learning. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2020, 5, 261–271.

- Marinescu, R.; Nicolae, M. Moocs. Challenges and Opportunities for Romanian Universities. In Let’s Build the Future through Learning Innovation! Roceanu, I., Ed.; “Carol I” National Defence University Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2014; Volume IV, pp. 70–77.

- Camadan, F.; Reisoglu, I.; Ursavas, Ö.F.; Mcilroy, D. How Teachers’ Personality Affect on Their Behavioral Intention to Use Tablet PC. IJILT 2018, 35, 12–28.

- Hsu, L. What Makes Good LMOOCs for EFL Learners? Learners’ Personal Characteristics and Information System Success Model. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2021, 1–25.

- Prayoga, T.; Abraham, J. Behavioral Intention to Use IoT Health Device: The Role of Perceived Usefulness, Facilitated Appropriation, Big Five Personality Traits, and Cultural Value Orientations. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2016, 6, 1751.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T.; Furnham, A. Mainly Openness: The Relationship between the Big Five Personality Traits and Learning Approaches. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2009, 19, 524–529.

- Nunes, A.; Limpo, T.; Castro, S.L. Effects of Age, Gender, and Personality on Individuals’ Behavioral Intention to Use Health Applications. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and E-Health, Funchal, Portugal, 22–23 March 2018; Scite Press: Setúbal, Portugal, 2018.

- Pourfeiz, J. Exploring the Relationship between Global Personality Traits and Attitudes toward Foreign Language Learning. In Proceedings of the 5th World Conference on Learning, Teaching and Educational Leadership, Prague, Portugal, 29–30 October 2014; Hursen, C., Ed.; Elsevier Science Bv: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 186, pp. 467–473.

- Hills, P.; Argyle, M. Emotional Stability as a Major Dimension of Happiness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 31, 1357–1364.

- Chen, S.Y.; Chang, Y.-M. The Impacts of Real Competition and Virtual Competition in Digital Game-Based Learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 104, 106171.

- Vandercruysse, S.; Vandewaetere, M.; Cornillie, F.; Clarebout, G. Competition and Students’ Perceptions in a Game-Based Language Learning Environment. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2013, 61, 927–950.

- Armstrong, J.S.; Kohn, A. No Contest: The Case against Competition. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 131.

- Credé, M.; Tynan, M.C.; Harms, P.D. Much Ado about Grit: A Meta-Analytic Synthesis of the Grit Literature. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 113, 492–511.

- Duckworth, A.L.; Quinn, P.D. Development and Validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit–S). J. Personal. Assess. 2009, 91, 166–174.

More

Information

Subjects:

Language & Linguistics

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No