| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guillermo Javier Zalazar | -- | 1763 | 2022-05-25 23:04:43 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | + 1 word(s) | 1764 | 2022-05-26 05:04:07 | | |

Video Upload Options

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is the most frequent cause of vertigo. As its name indicates, it is characterized by vertigo episodes of sudden onset and end, triggered by changes in head’s position with regard to gravity. It is located in the labyrinth, and its cause is mechanical. However, this is an etiologic diagnosis, reached after questioning and examining the patient. Based on what patients report, the duration of symptoms lasts seconds; however, many overestimate the duration of the vertiginous sensation. The trigger effect of positional changes is a key issue to be addressed. A great variability of autonomic symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, can accompany BPPV. Gait instability, headache, and additional neurologic complaints are potential red flags in the differential diagnosis. With a defined position trigger effect, it is the neurologist’s job to perform an examination to confirm the diagnosis of paroxysmal positional vertigo (PPV), and by virtue of the vertigo duration and nystagmus characteristics, to determine lesion localization (peripheral versus central) and to design a management plan.

1. Atypical Positional (APV)

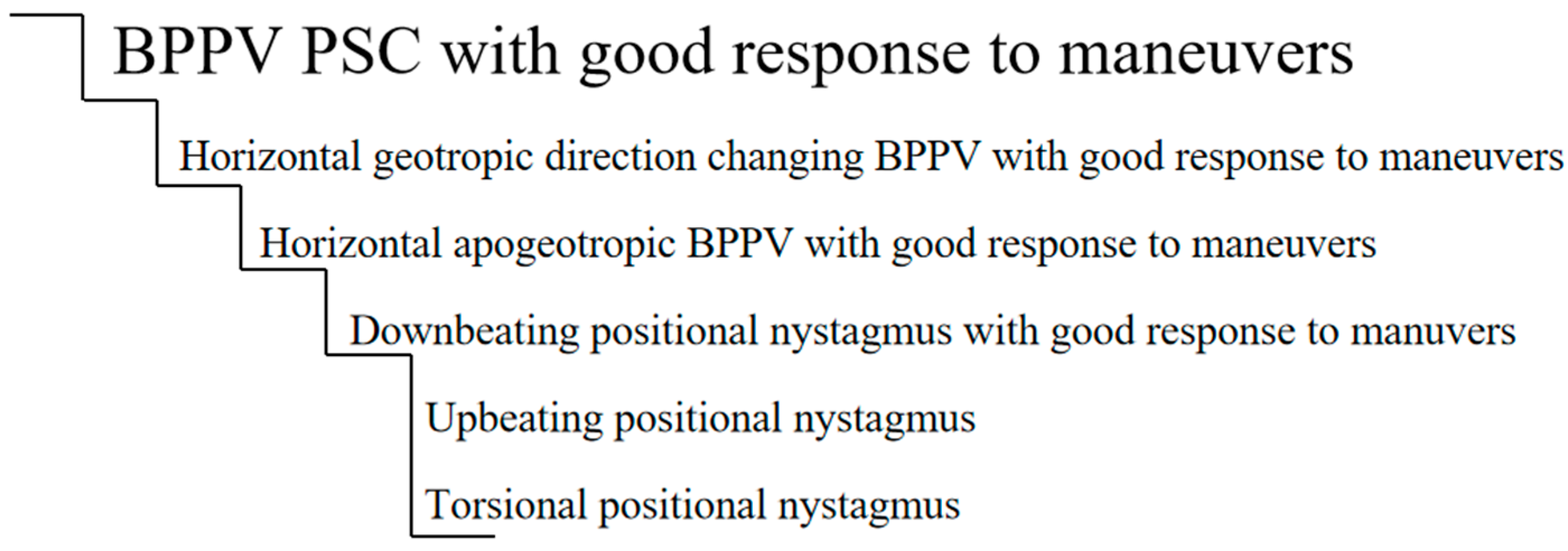

2. Cupula-Endolymph Density Alteration

2.1. Heavy Cupula

2.2. Light Cupula Syndrome

3. Apogeotropic and Geotropic Horizontal Nystagmus of Central Cause

4. Vestibular Paroxysmia

5. Vestibular Migraine

6. Inferior Vestibular Neuritis

7. Proposed Definition for APV and Atypical BPPV

-

Is accompanied by neurological disease signs/symptoms (this does not apply to posterior canal BPPV: in many instances, posterior canal BPPV occurs in patients with CNS disorders; it is unrelated to these and improves with an Epley maneuver [25]);

-

Appears during childhood, except post-HT;

-

Presents a purely direction-changing torsional nystagmus (purely vertical);

-

Has no latency;

-

Is of excessive duration;

-

Does not respond to the maneuvers;

-

Presents signs that persist throughout time.

-

The nystagmus does not fall into the classical description for the affected canal;

-

During its evolution, the typical signs of the suspected canal being affected appear;

-

It responds to repositioning maneuvers;

-

Central causes have been ruled out.

References

- Carmona, S.; Grinstein, G.; Weinschelbaum, R.; Zalazar, G. Topodiagnosis of the Inner Ear: Illustrative Clinical Cases. Ann. Otolaryngol. Rhinol. 2018, 5, 1201.

- Carmona, S.; Salazar, R.; Zalazar, G. Atypical Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo in a Case of Acoustic Neuroma. J. Otolaryngol. ENT Res. 2017, 8, 00261.

- Sergio, C.; Gabriela, G.; Romina, W.; Guillermo, Z. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: Differential Diagnosis in Children. Biomed. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2018, 2, 2437–2438.

- Califano, L.; Vassallo, A.; Melillo, M.G.; Mazzone, S.; Salafia, F. Direction-fixed paroxysmal nystagmus lateral canal benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo (BPPV): Another form of lateral canalolithiasis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2013, 33, 254–260.

- Cambi, J.; Astore, S.; Mandalà, M.; Trabalzini, F.; Nuti, D. Natural course of positional down-beating nystagmus of peripheral origin. J. Neurol. 2013, 260, 1489–1496.

- Vannucchi, P.; Pecci, R.; Giannoni, B. Posterior semicircular canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo presenting with torsional downbeating nystagmus: An apogeotropic variant. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2012, 2012, 413603.

- Carmona, S.; Zalazar, G.; Weisnchelbaum, R.; Grinstein, G.; Breinbauer, H.; Asprella Libonati, G. Downbeating Nystagmus in Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: An Apogeotropic Variant of Posterior Semicircular Canal. Curr. Opin. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 1, 301–305.

- Bertholon, P.; Chelikh, L.; Tringali, S.; Timoshenko, A.; Martin, C. Combined horizontal and posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in three patients with head trauma. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2005, 114, 105–110.

- Lagos, A.E.; Ramos, P.H.; Aracena-Carmona, K.; Novoa, I. Conversion from geotropic to apogeotropic direction changing positional nystagmus resulting in heavy cupula positional vertigo: Case report. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 87, 629–633.

- Hiruma, K.; Numata, T.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Tomemori, T.; Watanabe, R.; Okamoto, Y. Two types of direction-changing positional nystagmus with neutral points. Auris Nasus Larynx 2011, 38, 46–51.

- Shigeno, K.; Oku, R.; Takahashi, H.; Kumagami, H.; Nakashima, S. Static direction-changing horizontal positional nystagmus of peripheral origin. J. Vestib. Res. 2001, 11, 243–244.

- Kerber, K.A. Episodic Positional Dizziness. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2021, 27, 348–368.

- Nuti, D.; Zee, D.S.; Mandalà, M. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo: What We Do and Do Not Know. Semin. Neurol. 2020, 40, 49–58.

- Tang, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, P.; Feng, T.; Ou, Y.; Zheng, Y. Clinical Findings in Patients with Persistent Positional Nystagmus: The Designation of “Heavy and Light Cupula”. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 326.

- Zhang, S.L.; Tian, E.; Xu, W.C.; Zhu, Y.T.; Kong, W.J. Light Cupula: To Be or Not to Be? Curr. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 455–462.

- Walker, M.F.; Tian, J.; Shan, X.; Tamargo, R.J.; Ying, H.; Zee, D.S. The cerebellar nodulus/uvula integrates otolith signals for the translational vestibulo-ocular reflex. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13981.

- Choi, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Glasauer, S.; Kim, J.S. Central paroxysmal positional nystagmus: Characteristics and possible mechanisms. Neurology 2015, 84, 2238–2246.

- Takemori, S.; Cohen, B. Loss of visual suppression of vestibular nystagmus after flocculus lesions. Brain Res. 1974, 72, 213–224.

- Strupp, M.; Lopez-Escamez, J.A.; Kim, J.S.; Straumann, D.; Jen, J.C.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Brandt, T. Vestibular paroxysmia: Diagnostic criteria. J. Vestib. Res. 2016, 26, 409–415.

- Lempert, T.; Olesen, J.; Furman, J.; Waterston, J.; Seemungal, B.; Carey, J.; Bisdorff, A.; Versino, M.; Evers, S.; Newman-Toker, D. Vestibular migraine: Diagnostic criteria. J. Vestib. Res. 2012, 22, 167–172.

- Lechner, C.; Taylor, R.L.; Todd, C.; Macdougall, H.; Yavor, R.; Halmagyi, G.M.; Welgampola, M.S. Causes and characteristics of horizontal positional nystagmus. J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 1009–1017.

- Young, A.S.; Nham, B.; Bradshaw, A.P.; Calic, Z.; Pogson, J.M.; D’Souza, M.; Halmagyi, G.M.; Welgampola, M.S. Clinical, oculographic, and vestibular test characteristics of vestibular migraine. Cephalalgia 2021, 41, 1039–1052.

- Polensek, S.H.; Tusa, R.J. Nystagmus during Attacks of Vestibular Migraine: An Aid in Diagnosis. Audiol. Neurotol. 2010, 15, 241–246.

- ElSherif, M.; Reda, M.I.; Saadallah, H.; Mourad, M. Eye movements and imaging in vestibular migraine. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp. 2020, 71, 3–8.

- De Schutter, E.; Adham, Z.O.; Kattah, J.C. Central positional vertigo: A clinical-imaging study. Prog. Brain Res. 2019, 249, 345–360.