Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo is the most frequent cause of vertigo. As its name indicates, it is characterized by vertigo episodes of sudden onset and end, triggered by changes in head’s position with regard to gravity. It is located in the labyrinth, and its cause is mechanical. However, this is an etiologic diagnosis, reached after questioning and examining the patient. Based on what patients report, the duration of symptoms lasts seconds; however, many overestimate the duration of the vertiginous sensation. The trigger effect of positional changes is a key issue to be addressed. A great variability of autonomic symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, can accompany BPPV. Gait instability, headache, and additional neurologic complaints are potential red flags in the differential diagnosis. With a defined position trigger effect, it is the neurologist’s job to perform an examination to confirm the diagnosis of paroxysmal positional vertigo (PPV), and by virtue of the vertigo duration and nystagmus characteristics, to determine lesion localization (peripheral versus central) and to design a management plan.

1. Atypical Positional (APV)

In most patients, Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) presents with a typical description and physical examination, with no diagnostic difficulties. However, in some cases, there are hard-to-explain findings, which may result in diagnostic error.

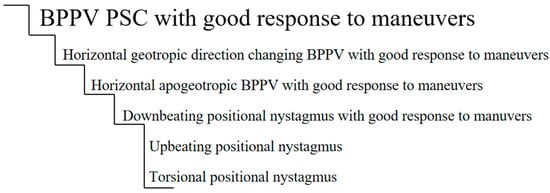

If we were to use a ladder to plot the degree of atypicality, we may find what is shown in Figure 1. This chart is a proposed ladder and is not intended to be definitive. At the top, we have the most frequent BPPV, one with posterior canal compromise and with an excellent response to maneuvers. As we go down the ladder, we find less frequent forms, which may overlap with positional vertigo of central causes.

Figure 1. Ladder of atypicality.

In recent years, many cases and series of cases have been published [

12,

13,

14] of patients with a clinical picture of positional vertigo, who were initially diagnosed as BPPV but whose final diagnosis was of CPPV or vestibular neuritis; these cases match what is represented in the ladder.

Other clinical pictures of atypical nystagmus have been described for BPPV, which were explained by the presence of otoconial particles in different parts of the canals. The characteristic they shared was that, in their evolution, after the maneuvers were performed, the typical findings of the affected canal BPPV appeared and were solved with repositioning maneuvers [

8,

9,

10,

11,

15]. These clinical pictures would be atypical BPPVs.

2. Cupula-Endolymph Density Alteration

2.1. Heavy Cupula

A heavy cupula is characterized by the presence of persistent (lasting longer than a minute) apogeotropic positional nystagmus with cephalic changes and of a null point. Some authors have proposed that the density of the cupula would increase as regards the endolymphatic density, thus producing an ampullofugal deflection that would facilitate the persistence of the position-changing apogeotropic nystagmus, depending on the cephalic position. Under normal conditions, the semicircular canals do not depend on gravity, taking into account that the cupula and the endolymph have the same density and therefore the same gravity. However, if the density of the cupula becomes heavier or lighter as compared to that of the endolymph, its deflection due to the presence of otolith remains (debris) alters its gravitational sensitivity. Hiruma et al. hypothesized that a heavy cupula would actually be more of an otoconial phenomenon than a gravitational change and set forth the possibility of a phenomenon in which particles float (“buoyancy”) in the horizontal canal, contrary to what happens in a light cupula, in which there would be an increase of endolymphatic density. In their 2011 paper, they mentioned that patients with a heavy cupula diagnosis responded to repositioning maneuvers, while light cupula patients did not [

23,

24].

2.2. Light Cupula Syndrome

The light cupula syndrome (LCS) is quite uncommon, but it should be taken into account as it can resemble a horizontal canal BPPV. Patients with LCS usually present with positional vertigo and a constant sensation of imbalance. Nystagmus lasts longer than a minute, is horizontal, geotropic, and direction-changing with head roll. It has no latency or tiredness, showing a constant slow phase velocity that does not fatigue, as is seen in positional alcohol nystagmus phase 1. In the supine position, there is a null point when rotating the head 20 or 30 degrees to the affected side, at which point the nystagmus subsides.

The term light cupula was coined by Shigeno in 2002, as it is believed that a direction-changing persistent nystagmus with head rotations is the result of an anti-gravitational deviation of the cupula in the lateral semicircular canal [

25].

When the cupula is light, it becomes gravity sensitive, and therefore, when the head is rotated to the affected side, the cupula will be persistently deflected. When the patient is in a sitting position, a spontaneous nystagmus may observed, which will stop when the head is tilted approximately 30 degrees to the front, as this puts the lateral canal in a position parallel to the horizontal plane. In some patients, the light cupula syndrome may be accompanied by unilateral hearing loss, which suggests that there is a concomitant labyrinth alteration. If the nystagmus is apogeotropic, it could be caused by an increase of endolymphatic density. Patients with LCS are refractory to the attempts to reposition the particles. The course of recovery is usually slow, and it takes some days or weeks [

26].

Despite the fact that positional vertigo and nystagmus caused by light cupula are similar to BPPV, it has not yet been determined if they are a variant of BPPV. Their pathogenesis is still unknown, and they are generally considered pathologic vestibular phenomena. There are many theories that explain why the cupula becomes lighter than the endolymph but only in the lateral canal, including the following: light debris attached to the cupula; a reduced cupula density as compared to normal endolymphatic density due to an altered homeostasis of sulphated proteoglycans, which are synthesized in the cupula; an increase in endolymphatic density due to chemical changes and a difference between perilymphatic and endolymphatic densities. Light cupula is still a mystery. The nystagmus it presents is similar to that of phase 1 positional alcohol nystagmus, in which the cupula is relatively lighter than the endolymph, as alcohol, which is less dense than water, enters the cupula quicker than the endolymph [

27].

The null point is the most important characteristic in the diagnosis of light cupula [

28]. The absence of any sign of alteration of central origin must also be considered, as this is an ear concomitant pathology (Ménière, Ramsay Hunt, Labyrinthitis).

The relatively specific change in cupula and endolymph density is dynamic. Light cupula might not be an independent pathology but a pathological condition or stage of an inner ear pathology [

29].

3. Apogeotropic and Geotropic Horizontal Nystagmus of Central Cause

It is a well-known fact that the cerebellar nodulus/uvula integrates otolith signals for the translational vestibulo-reflex [

30], and though it has always been said that pure horizontal nystagmus, without latency and of long duration, is central, the mechanism has been included in recent publications [

12,

31] where an abnormal perception causes this form of nystagmus: “If the bias is toward the nose, when the head is turned to the side while supine, there will be sustained, unwanted, horizontal positional nystagmus (apogeotropic type of central positional nystagmus) because of an inappropriate feedback signal indicating that the head is rotating when it is not”.

There is evidence that shows that the apogeotropic forms are caused by lesions in the nodulus, and that the geotropic ones would be caused by a compromise of the floculus [

32].

4. Vestibular Paroxysmia

Its clinical picture is characterized by brief vertigo attacks, which usually last less than a minute and which might occur many times a day. These episodes usually occur as a result of some cephalic movements and are accompanied by hyperacusis and/or tinnitus [

33].

We studied 38 patients with a Vestibular Paroxysmia diagnosis (unpublished data) who sought consultation due to spontaneous vertigo. The average age was 59 years.

Of the 38 patients, 20 (52.6%) were women and 18 (47.4%) were men.

Of the 38 patients, 19 referred positional vertigo, which represents 50%.

In addition, 47.3% (18 patients) presented positional nystagmus in the physical examination. In most of these cases, the characteristic was vertical (13 out of 18).

Hyperventilation was positive in 28.9% (11 patients).

5. Vestibular Migraine

One of the types of vertigo that, according to the Bárány Society, a patient may present during a vestibular migraine attack is positional vertigo [

34].

Approximately 65% of patients present positional vertigo (1 min to days, plus spontaneous vertigo, migraine symptoms, tinnitus, oscillopsia, feeling of auditory fullness, and/or subjective hearing loss) [

35,

36,

37,

38].

Central positional nystagmus is present in up to 100% of the attacks, with or without gait ataxia, which is present in 90% of the attacks [

35,

36,

37,

38].

Positional nystagmus has a variable pattern: persistent fixed-direction horizontal nystagmus, apogeotropic, downbeating, upbeating, and torsional nystagmus. Interictal may persist after a mild positional nystagmus in the dark [

35,

36,

37,

38].

In our database (unpublished data), where a total of 45 patients with a diagnosis of vestibular migraine and with an average age of 56.3 years were analyzed, 13 consulted due to positional vertigo; out of these patients, the following presented positional nystagmus of variable characteristics: eight had down-beat nystagmus, two had horizontal to the left, and two had vertical with a rotational component.

6. Inferior Vestibular Neuritis

Though it is not very common, a clinical picture of vestibular neuritis may produce postural symptoms. We described [

12] a patient with compromising of the posterior canal in the context of an inferior vestibular neuritis, who presented paroxysmal positional vertigo when the Dix-Hallpike maneuver was performed to the left, which resulted in a paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus. The vHIT show a gain reduction in the left posterior semicircular canal with corrective saccades, compatible with a clinical picture of inferior vestibular neuritis. A brain MRI was normal, and there was no response to repositioning maneuvers.

7. Proposed Definition for APV and Atypical BPPV

We consider that APV is the positional vertigo clinical picture, which

-

Is accompanied by neurological disease signs/symptoms (this does not apply to posterior canal BPPV: in many instances, posterior canal BPPV occurs in patients with CNS disorders; it is unrelated to these and improves with an Epley maneuver [

39]);

-

Appears during childhood, except post-HT;

-

Presents a purely direction-changing torsional nystagmus (purely vertical);

-

Has no latency;

-

Is of excessive duration;

-

Does not respond to the maneuvers;

-

Presents signs that persist throughout time.

In these cases, we must keep in mind that this could possibly be a clinical picture of central origin.

We consider that a BPPV is atypical when

-

The nystagmus does not fall into the classical description for the affected canal;

-

During its evolution, the typical signs of the suspected canal being affected appear;

-

It responds to repositioning maneuvers;

-

Central causes have been ruled out.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/audiolres12020018