Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | James Read | -- | 2064 | 2022-05-23 12:27:45 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2064 | 2022-05-24 04:56:29 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Read, J.; Critchley, R.; Hazael, R. Survivability Assessment. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23240 (accessed on 11 January 2026).

Read J, Critchley R, Hazael R. Survivability Assessment. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23240. Accessed January 11, 2026.

Read, James, Richard Critchley, Rachael Hazael. "Survivability Assessment" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23240 (accessed January 11, 2026).

Read, J., Critchley, R., & Hazael, R. (2022, May 23). Survivability Assessment. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/23240

Read, James, et al. "Survivability Assessment." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 May, 2022.

Copy Citation

Survivability assessment can be defined as the method by which the penetration performance of a protective material is measured. The key metric here is how effective the material is at dissipating energy throughout its molecular matrix, thereby protecting the material’s integrity and providing enhanced protection to the user from both ballistic and non-ballistic threats.

tissue analogue

ballistic gelatine

1. Survivability Assessment

Because of protective materials’ applications, they are subjected to a rigorous qualification process that describes how the materials should be tested and the pass criteria for both ballistic- and-stab resistant materials [1]. This assessment is traditionally conducted by applying tensile load to the material sample until failure occurs [2]. Thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the material’s limitations and the applicability for its intended purpose.

This alone cannot be relied upon to portray a full perspective of what is happening on impact. To accurately assess a projectile’s influence on the human body, the specialist field of wound ballistics is used. Wound ballistics primarily concerns itself with three types of projectiles (handgun bullets, bullets from long-range weapons, and fragmentation), their differences in behaviour within the target, and wound channel formation [3].

Upon impact with the front face of the simulant, the projectile decelerates, which, as it continues inside the medium, exhibits radial energy, creating the ‘Temporary Cavity’ [4]. This reaction can also be seen to ‘pulse’ when the energy exerted inside the body and the entry and exit of air into the wound causes expansion and contraction of the tissue before collapsing because of the human anatomy’s internal elasticity [3]. Simulants such as gelatine have been reported to be most desirable for this research because their elasticity is similar to that of the human torso [3], but because of this elasticity, the cavity collapses immediately [5], which, without the use of high-speed video footage, would be rendered useless because of the inability for the human eye to witness a millisecond reaction.

The permanent cavity is more simplistic; this is the pathway the projectile has created, which can vary in size and routing depending on factors such as tissue density, muscle content, and bone location [3] as well as projectile size, yaw, tumbling, and the angle of entry [6]. The permanent cavity is traditionally clearly identified post impact [7], but the analysis of the temporary cavity can better identify the amount of force generated upon projectile impact and the dissipation of that energy throughout the surrounding tissues/organs.

2. Simulants

Traditionally, human cadavers and animals have been used to assess wounding and behind-armour effects [8], but they do not provide an accurate enough material when an assessment of penetration or perforation is required [9]. With more ethical considerations at the forefront of any research project in the modern day, simulants have become the go-to material for many researchers. The cost and availability benefits are notable, whilst the ability to replicate and validate existing experiments is the main benefit compared with animal anatomy, which differs with the individual animal [3]. Whilst these top-level advantages provide some justification for using simulants, there are also drawbacks that should be examined.

2.1. Ballistic Gelatine

Ballistic gelatine is a widely accepted material for survivability assessment and wound ballistic research. Two types are readily available: Type A, which is derived from acid-treated collagen found in pig skin, and Type B, which is derived from alkali-treated beef skin [10]. As the human anatomy is more closely aligned to that of porcine anatomy [8][11], the most widely used gelatine is Type A. Type A material consists of an acid-treated collagen protein found in animal products [8] and is manufactured in 10 and 20% mass constructs before being conditioned at specific temperatures before use. Both 10 and 20% constructs’ ability to replicate the human body is measured by their strength and stiffness properties, which are referred to as the ‘bloom number’. Ballistic gelatine is available in 50–300 bloom constructs [8]; however, the Type A bloom number must reside between 250 and 300 to provide accurate results in wound ballistic research [12]. To provide the bloom number, a 112 g sample of 6.67 w/w gelatine is manufactured to standardised time and temperature systems before undergoing a compressive test resulting in the bloom figure [13].

It has been reported that the concentration and temperature during preparation can also influence the performance ability [9] but should be controlled using calibration.

Currently calibrated using the US Fackler method [14], the 10% construct (Figure 1) is reported to be the most beneficial for uses in which penetrating impact analyses are required [15]. Manufactured with 90 parts water and 10 parts gelatine, the material can be affected by water quality, temperature, and post-manufacture conditioning [13], leading to inconsistencies in output data. However, with variables that can be controlled in lab environments, this material has historically shown its viability in wound ballistic research.

By contrast, the 20% construct is uncalibrated [15] and is often referred to as ‘NATO’ gelatine [13], which is manufactured with 80 parts water and 20 parts gelatine powder [3]. It has been reported that 20% gelatine is superior to 10% gelatine when examining deflection and force data, with outputs showing reactions closer to those of human responses [16]; however, this evidence is singular, and the claim that performance is only viable for these measurements cannot be found elsewhere. Similar to the 10% construct, this material also exhibits issues with water quality, temperature, and post-manufacture conditioning, but because of the uncalibrated manufacturing technique [12], researchers can vary their manufacturing method, increasing the difficulty in experiment repeatability.

Regardless of which construct of ballistic gelatine is used, the shelf life remains poor [12][13]. Polymer-based gels, such as the brain tissue simulants Sylgard and Styrene-Ethylene-Butylene-Styrene (SEBS), which is a thermoplastic elastomer [17], have been developed to provide a suitable alternative with similar performance properties to those of ballistic gelatine to measure behind-armour blunt trauma and back-face deformation. This may eliminate storage requirements and alleviate shelf-life issues; however, the existing issue of manufacturing variable control remains of concern for survivability.

Figure 1. 10% ballistic gelatine [15].

2.2. Perma-Gel®

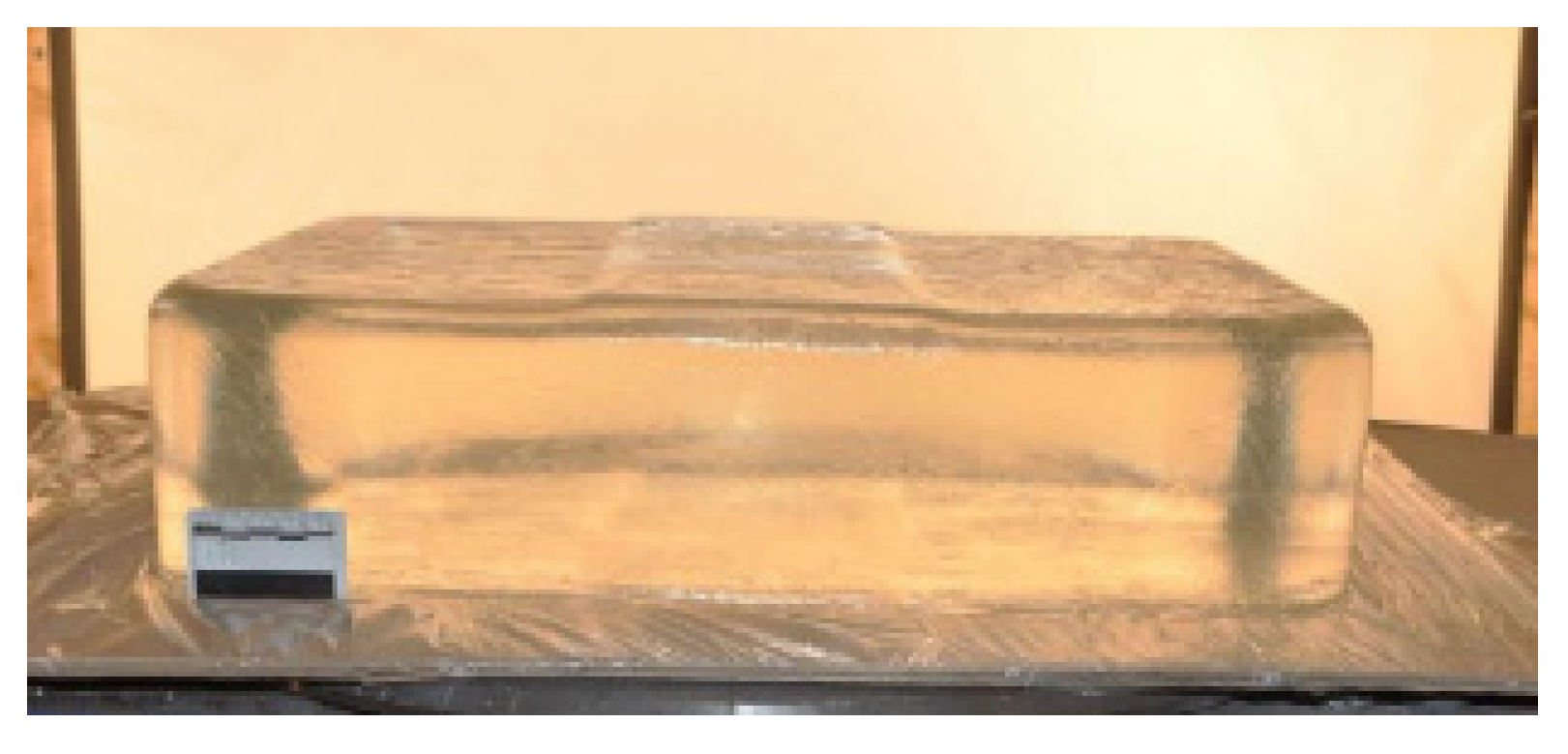

Although 10 and 20% constructs are valid means by which to assess multiple technologies within both the defence and civilian research fields, Perma-Gel® (shown in Figure 2) provides re-meltable and re-castable properties that reduce both project costs and environmental impacts yet has been reported to exhibit similar performance properties to both types of gelatine [18][19]. Perma-Gel can be categorised as a transparent synthetic thermoplastic material that is manufactured using gellants, mineral oil, and butylated hydroxytoluene [19]. Previous research has also shown that this material’s response to impact is similar to that of other co-polymers of similar compositions [20]. Other advantages include increased shelf life in comparison to gelatine; no pre-conditioning being required, cutting project time; and its transparency and ability to analyse various wound ballistics perimeters, such as temporary and permanent cavities [3][4]. It has been reported that, once remelted and reformed, the material behaves differently and can affect Depth of Penetration values [12]. Although this has been reported, no work appears to have further explored why this phenomenon occurs. Furthermore, there have been reports that the material may only be suitable for reuse between 10–15 times, and the more the material is remelted and reused, a yellow tint appears to form within the blocks, which may interfere with output data [13]. A. Mabbot’s work provided insight into Perma-Gel® and confirmed that either information on these data is unverified or that gaps exist in the literature [13].

Figure 2. Perma-Gel block [13].

2.3. Ballistic Soap

Ballistic soap (shown in Figure 3) has been reported to produce the same desirable characteristics as gelatine (density, isotropy, and homogeneity) [21]; however, it lacks the elasticity properties required for survivability assessment. This material is typically manufactured using the hydrolysis of fats with a strong base to form sodium or potassium salts of carboxylic acid. This, paired with the remaining glycerine by-product, generates long aliphatic hydrocarbon chains that govern the behaviour of ballistic soap [22]. Upon the impact of a bullet, ballistic soap exhibits plastic-like behaviour and is thus more suited to capturing information on the maximum sizes of the temporary cavity rather than exploring the permanent cavity pathway. This can be carried out using X-ray or by cutting into the block to reveal the wound profile [3]. It is thus only viable to use this material for partial experimental data capture, as all-encompassing use would result in invalid conclusions because of the inability to analyse the full extent of the damage caused by the bullet impact and inaccurate results.

Unlike gelatine, ballistic soap has a much longer storage life (a number of years as opposed to days) [9]; this is predominantly due to the complex glycerine manufacturing process, which means the material is purchased by the researcher as opposed to being made on site. Prior to any data capture, the material should undergo baseline testing to ensure that viable performance is shown and that a comparison can be made with previous/future blocks. However, as these are not reusable materials, nor are they transparent, the opportunity to realise cost savings and use high-speed video footage to analyse results is limited.

Figure 3. Ballistic soap [23].

2.4. Roma Plastilina® Clay No. 1

Traditionally used to measure behind-armour blunt trauma (BABT), Roma Plastilina No. 1 modelling clay consists of minerals, oils, and waxes [24][25]. It is placed within a 420 × 350 × 100 mm steel tray with one large face exposed, ensuring that no air gaps exist [1]. The exposed face is made smooth by scraping the material to align with the edges of the steel tray, thereby creating a defect-free face.

Because of the complexity in manufacture, ROMA Plastilina No. 1 is traditionally bought from a supplier before being moulded, as stated above, and conditioned within laboratory conditions [25].

Prior to exposure to experimental conditions, the moulded blocks must be calibrated to ensure that the material aligns with both the National Institute of Justice [26] and CAST standards [27] depending on the customer base and test location. This begins with the material being conditioned to 30 °C for at least 3 h prior to calibration. The material is then led flat, and a minimum of 3 drop tests from 1.5 m ± 0.5 (2 m for NIJ) are conducted using a 1.043 kg spherical steel ball 63.5 mm in diameter [26][27]. To pass, the material must not decompress more than 15 mm ± 1.5 mm for CAST and 20 mm ± 3 mm for NIJ, which is measured using a vernier calliper from the top of the tray [28].

Once calibrated, experimentation must be conducted at a controlled temperature [29], ensuring that the output data remain consistent and no premature ageing of the material occurs [30]. Additionally, the material is considered to be out of calibration within 45 min [31].

The protective material is located centrally to the front face of the Plastilina and secured to minimise movement; this is highlighted in Figure 4. Once testing has been completed, the protective material is removed from the front face of the Plastilina, and any depth of indentation is measured using a vernier calliper or another agreed-upon method [15]. It should be noted that, because of the construction of Roma Clay, the mixture equates to roughly twice the density of human tissue and is thus used as a worst-case testing material [29].

Figure 4. Roma Plastilina No. 1 used as a backing material for survivability assessment [15].

Survivability assessment can be achieved using a magnitude of materials [32]. Regardless of which gelatine or alternative synthetic material is used, excessive water is used and waste is generated during experimental regimes, which, in a world that is aiming to reduce its impact on climate change, is unacceptable, and a shift in approach is required. To further elaborate on the advantages and disadvantages of the previously discussed materials, see Table 1.

| Simulant Name | Reported Advantages | Reported Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Gelatine | Removes ethical concerns | Lacks biomechanical properties of organs and tissues |

| Accepted as human tissue simulant | Only represents human torso/porcine thigh | |

| History of extensive testing | Radial cracks occur during bullet penetration | |

| Demonstrates temporary and permanent cavity mechanics | Affected by bacterial contamination, decomposition, and short storage life (2–3 days prior to use) | |

| Elasticity similar to human tissue | Different blooms used | |

| Transparency | Varying concentrations | |

| Not re-useable | ||

| Temperature-dependant—must be kept refrigerated | ||

| No standard manufacturing procedure | ||

| Perma-Gel® | Reported to be re-useable (8–15 times) | Limited data to confirm claims on performance and re-useability |

| No pre-conditioning required | Only comes in one block size | |

| Clear and odourless material | Difficulties with disposal (synthetic polymer) | |

| Captures permanent cavity | ||

| Displays temporary cavity formation | ||

| Ballistic Soap | Long storage life | Not re-useable |

| No pre-conditioning required | Purchase only—not made in-house because of manufacturing complexity | |

| Captures max size of temporary cavity (viewed in place) | Opaque nature—limited opportunity to review high-speed video | |

| Non-elastic nature | ||

| Roma Plastilina® | History of extensive testing | Opaque nature—limited opportunity to review high-speed video |

| No pre-conditioning required | Non-elastic nature | |

| Moulding to shapes is easy | Purchase only—not made in-house because of manufacturing complexity |

References

- Payne, T.; O’Rourke, S.; Malbon, C. Body Armour Standard (2017); CAST Publication Number: 012/17; Home Office: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–92. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/634517/Home_Office_Body_Armour_Standard.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- British Standards Institute. Protective Clothing and Equipment for Use in Violent Situations and in Training—Blunt Trauma Torso, Shoulder, Abdomen and Genital Protectors. Requirements and Test Methods. 2003. Available online: https://shop.bsigroup.com/products/protective-clothing-and-equipment-for-use-in-violent-situations-and-in-training-blunt-trauma-torso-shoulder-abdomen-and-genital-protectors-requirements-and-test-methods/standard (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Coupland, R.M.; Rothchild, M.A.; Thali, M.J.; Kneubuehl, B.P. Wound Ballistics: Basics and Applications; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 87–137.

- Amato, J.J.; Rich, N.M.; Lawson, N.S.; Gruber, R.P.; Billy, L.J. Temporary Cavity Effects in High Blood Vessel Injury by High Velocity Missiles. 1970, pp. 1–15. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD0713504.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Schyma, C.; Madea, B. Evaluation of the temporary cavity in ordnance gelatine. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 214, 82–87.

- Fackler, M.; Brown, A.J.; Johnson, D. Wound Ballistics Review—2000 Number 3. J. Int. Wound Ballist. Assoc. 1995, 4, 1–25. Available online: http://thinlineweapons.com/IWBA/2000-Vol4No3.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Ordog, G.J.; Wasserberger, J.; Balasubramanium, S. Wound ballistics: Theory and practice. Ann. Emerg. Med. 1984, 13, 1113–1122.

- Humphrey, C.L. Characterisation of Soft Tissue and Skeletal Bullet Wound Trauma and Three-Dimensional Anatomical Modelling. 2018, pp. 23–32. Available online: https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/handle/2440/112985?mode=full (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- Sellier, K.; Kneubuehl, B. Wound Ballistics and the Scientific Background; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 1–479.

- Hanani, Z.A.N. Gelatin. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 191–195.

- Maiden, N. Historical overview of wound ballistics research. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2009, 5, 85–89.

- Carr, D.J.; Stevenson, T.; Mahoney, P.F. The use of gelatine in wound ballistics research. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2018, 132, 1659–1664.

- Mabbott, A. The Overmatching of UK Police Body Armour. Ph.D. Thesis, Cranfield University, Cranfield, UK, 2015; pp. 35–75. Available online: https://dspace.lib.cranfield.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1826/10515/Mabbott2015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 October 2021).

- Nicholas, N.C.; Welsch, J.R. Institute for Non-Lethal Defense Technologies Report: Ballistic Gelatin; Applied Research Laboratory—Pennsylvania State University: Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 1–28. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235099580_Institute_for_Non-Lethal_Defense_Technologies_Report_Ballistic_Gelatin (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Read, J.; Critchley, R.; Hazael, R.; Peare, A. Penetration Performance of Protective Materials from Crossbow Attack. Research Thesis, Cranfield University, Cranfield, UK, 2021; pp. 1–78.

- Maiden, N.R. The Assessment of Bullet Wound Trauma Dynamics and the Potential Role of Anatomical Models; The University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2014; pp. 8–204. Available online: https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/99527/2/02whole.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Koene, L.; Papy, A. Towards a better, science-based, evaluation of kinetic non-lethal weapons. Int. J. Intell. Def. Support Syst. 2011, 4, 169–186.

- Mabbott, A.; Carr, D.J.; Champion, S.; Malbon, C. Comparison of porcine thorax to gelatine blocks for wound ballistics studies. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2016, 130, 1353–1362.

- Appleby-Thomas, G.J.; Wood, D.C.; Hameed, A.; Painter, J.; Le-Seelleur, V.; Fitzmaurice, B.C. Investigation of the high-strain rate (shock and ballistic) response of the elastomeric tissue simulant Perma-Gel®. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2016, 94, 74–82.

- Pervin, F.; Chen, W.W. Mechanically Similar Gel Simulants for Brain Tissues. In Conference Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Mechanics Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 9–13.

- Pirlot, M.; Dyckmans, G.; Bastin, I. Soap and gelatine for simulating human body tissue: An experimental and numerical evaluation. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium of Ballistics, Interlaken, Switzerland, 7–11 May 2001; Abal, R., Ed.; Royal Military Academy: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; pp. 1–9. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marc-Pirlot/publication/266459600_SOAP_AND_GELATINE_FOR_SIMULATING_HUMAN_BODY_TISSUE_AN_EXPERIMENTAL_AND_NUMERICAL_EVALUATION/links/54dc60bc0cf23fe133b141e0/SOAP-AND-GELATINE-FOR-SIMULATING-HUMAN-BODY-TISSUE-AN-EXPERIMENTAL-AND-NUMERICAL-EVALUATION.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2021).

- Shepherd, C.J.; Appleby-Thomas, G.J.; Wilgeroth, J.M.; Hazell, P.J.; Allsop, D.F. On the response of ballistic soap to one-dimensional shock loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2011, 38, 981–988.

- Defensible Ballistics. Ballistic Soap (Large Block)—Defensible Ballistics. 2022. Available online: https://www.defensible.co.uk/products/p/ballistic-soap-large-block (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- ArtMolds. Roma Plastilina No. 1 Material Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.artmolds.com/pub/customfile/MSDS_ROMA_1.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Hernandez, C.; Buchely, M.F.; Maranon, A. Dynamic characterization of Roma Plastilina No. 1 from Drop Test and inverse analysis. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 100, 158–168.

- National Institute of Justice. Ballistic Resistance of Personal Body Armor, NIJ Standard-0101.04|National Institute of Justice. NIJ Standard-0101.04 United States of America: National Institute of Justice-USA. September 2000; pp. 1–65. Available online: https://nij.ojp.gov/library/publications/ballistic-resistance-personal-body-armor-nij-standard-010104 (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Croft, J.; Longhurst, D. HOSDB Body Armour Standards for UK Police (2007). Part 2: Ballistic Resistance. 39/07/B Home Office. 2007, pp. 1–36. Available online: https://www.bodyarmornews.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/HOSDB__2007_-_part_2.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Suppitaksakul, C. A measuring set for visualization of ballistic impact on soft armor. In Proceedings of the 2010 7th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks and Digital Signal Processing, CSNDSP 2010, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 21–23 July 2010; IEEE Computer Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 359–363.

- EnvironMolds. Technical Bulletin: Roma Plastilina No.1 Ballistic Clay. 2008. Available online: https://www.artmolds.com/pdf/RomaPlastilinaNo1TechBulletin.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Tao, R.; Rice, K.D.; Djakeu, A.S.; Mrozek, R.A.; Cole, S.T.; Freeney, R.M.; Forster, A.M. Rheological Characterization of Next-Generation Ballistic Witness Materials for Body Armor Testing. Polymers 2019, 11, 447.

- Mrozek, R.; Edwards, T.; Bain, E.; Cole, S.; Napadensky, E.; Freeney, R. Developing an Alternative to Roma Plastilina #1 as a Ballistic Backing Material for the Ballistic Testing of Body Armor. In Conference Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Mechanics Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 297–299.

- Malbon, C.; Carr, D. Comparison of Backing Materials Used in the Testing of Ballistic Protective Body Armour; Cranfield Online Research Data (CORD): Cranfield, UK, 2018; p. 1. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17862/CRANFIELD.RD.7347245.V1 (accessed on 8 March 2022).

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

785

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No