| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lixin Liu | -- | 1548 | 2022-05-18 10:21:31 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | -14 word(s) | 1534 | 2022-05-19 03:56:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

The eye, the photoreceptive organ used to perceive the external environment, is of great importance to humans. It has been proven that some diseases in humans are accompanied by fundus changes; therefore, the health status of people may be interpreted from retinal images. However, the human eye is not a perfect refractive system for the existence of ocular aberrations. These aberrations not only affect the ability of human visual discrimination and recognition, but restrict the observation of the fine structures of human eye and reduce the possibility of exploring the mechanisms of eye disease. Adaptive optics (AO) is a technique that corrects optical wavefront aberrations. Once integrated into ophthalmoscopes, AO enables retinal imaging at the cellular level.

1. Introduction

2. Principles and Methods

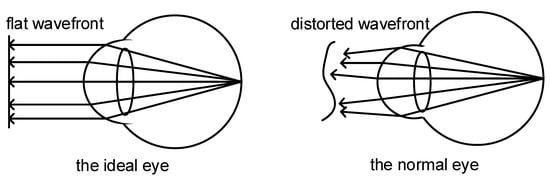

2.1. Wavefront Aberration in Human Eyes

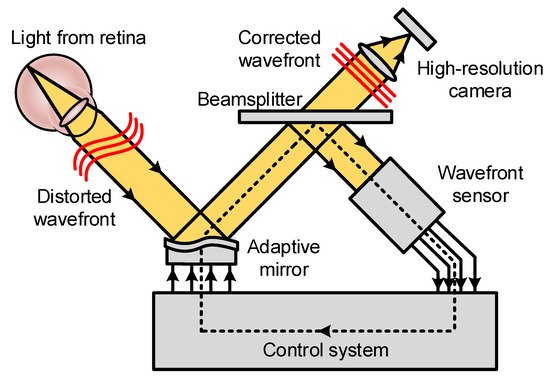

2.2. Basic Principles of Adaptive Optics

2.3. Sensorless AO and Computational AO

References

- Huang, D.; Swanson, E.A.; Lin, C.P.; Schuman, J.S.; Stinson, W.G.; Chang, W.; Hee, M.R.; Flotte, T.; Gregory, K.; Puliafito, G.A.; et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science 1991, 254, 1178–1181.

- Miller, D.T.; Williams, D.R.; Morris, G.M.; Liang, J. Images of cone photoreceptors in the living human eye. Vis. Res. 1996, 36, 1067–1079.

- Wade, A.; Fitzke, F. A fast, robust pattern recognition system for low light level image registration and its application to retinal imaging. Opt. Express 1998, 3, 190–197.

- Babcock, H.W. The possibility of compensating astronomical seeing. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 1953, 65, 229–236.

- Liang, J.; Grimm, B.; Goelz, S.; Bille, J.F. Objective measurement of wave aberrations of the human eye with the use of a Hartmann–Shack wave-front sensor. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1994, 11, 1949–1957.

- Clarkson, D. Adaptive optics in ophthalmology-Emergence of diagnostic tools. Optician 2007, 234, 38–39.

- Godara, P.; Dubis, A.M.; Roorda, A.; Duncan, J.L.; Carroll, J. Adaptive optics retinal imaging: Emerging clinical applications. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2010, 87, 930–941.

- Burns, S.A.; Elsner, A.E.; Sapoznik, K.A.; Warner, R.L.; Gast, T.J. Adaptive optics imaging of the human retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2019, 68, 1–30.

- Gill, J.S.; Moosajee, M.; Dubis, A.M. Cellular imaging of inherited retinal diseases using adaptive optics. Eye 2019, 33, 1683–1698.

- Bedggood, P.; Metha, A. Adaptive optics imaging of the retinal microvasculature. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2020, 103, 112–122.

- Porter, J.; Guirao, A.; Cox, I.G.; Williams, D.R. Monochromatic aberrations of the human eye in a large population. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 2001, 18, 1793–1803.

- Bille, J.F. High Resolution Imaging in Microscopy and Ophthalmology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019.

- Akyol, E.; Hagag, A.M.; Sivaprasad, S.; Lotery, A.J. Adaptive optics: Principles and applications in ophthalmology. Eye 2021, 35, 244–264.

- Kozak, I. Retinal imaging using adaptive optics technology. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 28, 117–122.

- Hampson, K.M.; Turcotte, R.; Miller, D.T.; Kurokawa, K.; Males, J.R.; Ji, N.; Booth, M.J. Adaptive optics for high-resolution imaging. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 68.

- Roorda, A. Adaptive optics for studying visual function: A comprehensive review. J. Vis. 2011, 11, 6.

- Hofer, H.; Sredar, N.; Queener, H.; Li, C.; Porter, J. Wavefront sensorless adaptive optics ophthalmoscopy in the human eye. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 14160–14171.

- Wen, L.; Yang, P.; Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Chen, S.; Xu, B. A high speed model-based approach for wavefront sensorless adaptive optics systems. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 99, 124–132.

- Wong, K.S.K.; Jian, Y.F.; Cua, M.; Bonora, S.; Zawadzki, R.J.; Sarunic, M.V. In vivo imaging of human photoreceptor mosaic with wavefront sensorless adaptive optics optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Opt. Express 2015, 6, 580–590.

- Polans, J.; Keller, B.; Carrasco-Zevallos, O.M.; LaRocca, F.; Cole, E.; Whitson, H.E.; Lad, E.M.; Farsiu, S.; Izatt, J.A. Wide-field retinal optical coherence tomography with wavefront sensorless adaptive optics for enhanced imaging of targeted regions. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 16–37.

- Zhou, X.L.; Bedggood, P.; Bui, B.; Nguyen, C.T.O.; He, Z.; Metha, A. Contrast-based sensorless adaptive optics for retinal imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2015, 6, 3577–3595.

- Adie, S.G.; Graf, B.W.; Ahmad, A.; Carney, P.S.; Boppart, S.A. Computational adaptive optics for broadband optical interferometric tomography of biological tissue. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7175–7180.

- Liu, Y.-Z.; Shemonski, N.D.; Adie, S.G.; Ahmad, A.; Bower, A.J.; Carney, P.S.; Boppart, S.A. Computed optical interferometric tomography for high-speed volumetric cellular imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2014, 5, 2988–3000.

- South, F.A.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Bower, A.J.; Xu, Y.; Carney, P.S.; Boppart, S.A. Wavefront measurement using computational adaptive optics. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A Opt. Image Sci. Vis. 2018, 35, 466–473.

- Liu, Y.-Z.; South, F.A.; Xu, Y.; Carney, P.S.; Boppart, S.A. Computational optical coherence tomography . Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 1549–1574.

- Booth, M.J. Adaptive optics in microscopy. Philos. Transact. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2007, 365, 2829–2843.

- Zommer, S.; Ribak, E.N.; Lipson, S.G.; Adler, J. Simulated annealing in ocular adaptive optics. Opt. Lett. 2006, 31, 939–941.

- Vorontsov, M.A. Decoupled stochastic parallel gradient descent optimization for adaptive optics: Integrated approach for wave-front sensor information fusion. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2002, 19, 356–368.

- Huang, L.; Rao, C. Wavefront sensorless adaptive optics: A general model-based approach. Opt. Express 2011, 19, 371–379.

- Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, B.; Chu, J. Hill-climbing algorithm based on Zernike modes for wavefront sensorless adaptive optics. Opt. Eng. 2013, 52, 016601.

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wang, M.; Jia, J. Wavefront sensorless adaptive optics based on the trust region method. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 1235–1237.

- Jian, Y.; Lee, S.; Ju, M.; Heisler, M.; Ding, W.; Zawadzki, R.; Bonora, S.; Sarunic, M. Lens-based wavefront sensorless adaptive optics swept source OCT. Sci. Rep. 2015, 6, 27620.

- Camino, A.; Ng, R.; Huang, J.; Guo, Y.; Ni, S.; Jia, Y.; Huang, D.; Jian, Y. Depth-resolved optimization of real-time sensorless adaptive optics optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 2612–2615.

- Verstraete, H.R.G.W.; Heisler, M.; Ju, M.J.; Wahl, D.; Bliek, L.; Kalkman, J.; Bonora, S.; Jian, Y.; Verhaegen, M.; Sarunic, M.V. Wavefront sensorless adaptive optics OCT with the DONE algorithm for in vivo human retinal imaging. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 2261–2275.

- Xu, Z.; Yang, P.; Hu, K.; Xu, B.; Li, H. Deep learning control model for adaptive optics systems. Appl. Opt. 2019, 58, 1998–2009.

- Hu, K.; Xu, B.; Xu, Z.; Wen, L.; Yang, P.; Wang, S.; Dong, L. Self-learning control for wavefront sensorless adaptive optics system through deep reinforcement learning. Optik 2019, 178, 785–793.

- Durech, E.; Newberry, W.; Franke, J.; Sarunic, M. Wavefront sensor-less adaptive optics using deep reinforcement learning. Biomed. Opt. Express 2021, 12, 5423–5438.

- Cunefare, D.; Langlo, C.S.; Patterson, E.J.; Blau, S.; Dubra, A.; Carroll, J.; Farsiu, S. Deep learning based detection of cone photoreceptors with multimodal adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscope images of achromatopsia. Biomed. Opt. Express 2018, 9, 3740–3756.

- Cunefare, D.; Huckenpahler, A.L.; Patterson, E.J.; Dubra, A.; Farsiu, S. RAC-CNN: Multimodal deep learning based automatic detection and classification of rod and cone photoreceptors in adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscope images. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 3815–3832.

- Zhu, D.; Wang, R.; Žurauskas, M.; Pande, P.; Bi, J.; Yuan, Q.; Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Boppart, S.A. Automated fast computational adaptive optics for optical coherence tomography based on a stochastic parallel gradient descent algorithm. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 23306–23319.