| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gianluca Polgar | -- | 3648 | 2022-04-27 11:40:20 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -9 word(s) | 3639 | 2022-04-28 03:16:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

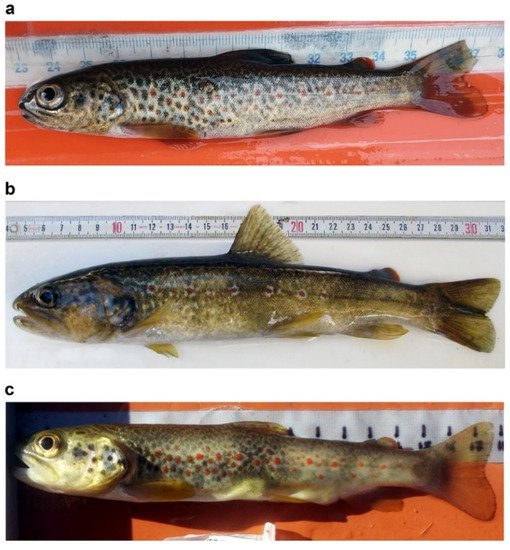

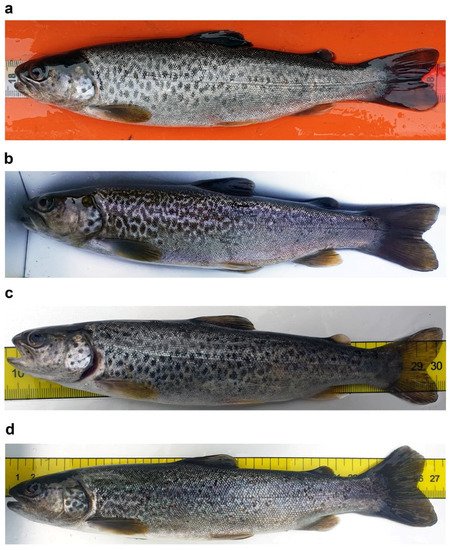

Among the valid nominal taxa of the native trouts described in the Italian peninsula and the major Italian islands, Salmo cettii Rafinesque-Schmaltz 1810 was described from Sicily (type locality: Val Demone in northeastern Sicily and Val di Noto in southeastern Sicily, no types known). S. marmoratus (Cuvier 1829) is a subendemism of northern Italy described from the “lacs de Lombardie" (syntypes not available). S. cenerinus Nardo 1847 was described from northeastern Italy (type locality: not far from the sea, in rivers draining to the Venetian lagoon; no types known). The original description of S. cenerinus was written from the late 1700s to the early 1800s by S. Chiereghin, and published posthumously; a summary of this description was first published by Nardo. S. macrostigma (Duméril 1858) has been considered by several authors as an Italian trout; however, it was described from North Africa (type locality: Oued-el-Abaïch, Kabylie, Algeria). S. ghigii Pomini 1941 was described from central Italy (type locality: Sagittario River; no types known). S. fibreni Zerunian and Gandolfi 1990, described from the Lake Posta Fibreno in central Italy, and S. carpio Linnaeus 1758, described from Lake Garda, are restricted endemisms defined by ecomorphological and genetic traits. The island of Sardinia might host an undescribed Salmo species (Segherloo et al.).

1. Native Italian Trouts and the Taxonomy of the “Peninsular Trout”

2. Phylogeny and Phylogeography of S. marmoratus

3. Presence of S. ghigii in the Italian Alpine and Subalpine Region

References

- Nardo, G.D. Sinonimia Moderna delle Specie Registrate nell’Opera Intitolata: "Descrizione de’ Crostacei, de’ Testacei e de’ Pesci che Abitanno le Lagune e Golfo Veneto Rappresentati in Figure à Chiaro-Scuro ed a Colori”; Antonelli: Venezia, Italy, 1847.

- Zerunian, S. Iconografia dei Pesci delle Acque Interne d’Italia; Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio (Direzione Conservazione Natura). Unione zoologica Italiana. Istituto Nazionale Fauna Selvatica. Tipolitografia F.G. Savigliano sul Panaro: Modena, Italy, 2002.

- Bovero, S.; Candiotto, A.; Ceppa, L.; Giuntoli, F.; Pascale, M.; Perosino, G.C. Stato dell’ittiofauna nei fiumi e torrenti del Piemonte. Riv. Piemont Stor. Nat. 2021, 42, 135–160.

- Nardo, G.D. Cenni Storico Critici sui Lavori Pubblicati Specialmente nel Nostro Secolo che Illustrano la Storia Naturale degli Animali Vertebrati della Veneta Terraferma ed Appendice Relativa ai Tentativi Fatti nelle Provincie Venete sulla Piscicoltura e sulla Propagazione Artifiziale del Pesce di Acqua Dolce; Grimaldo: Venice, Italy, 1875.

- Heckel, J.J.; Kner, R. Die Süsswasserfische der Österreichischen Monarchie, mit Rücksicht auf die Angränzenden Länder; von Engelmann, W.: Leipzig, Germany, 1857.

- Cuvier, G.; Valenciennes, A. Histoire Naturelle des Poissons. Tome vingt et unième. Suite du Livre vingt et unième et des Clupéoïdes. Livre vingt-deuxième. De la Famille des Salmonoïdes; Bertrand, P., at Berger-Levrault: Strasbourg, France, 1848.

- Kottelat, M. European freshwater fishes. Biologia 1997, 52 (Suppl. S5), 1–271.

- Pomini, F.P. Ricerche sui Salmo dell’Italia peninsulare. I. La trota del Sagittario (Abruzzi): Salmo ghigii (n. sp.). Atti. Soc. Ital. Sci. Nat. Milano 1941, 80, 33–48.

- Kottelat, M.; Freyhof, J. Handbook of European Freshwater Fishes; Kottelat, M., Freyhof, J., Eds.; Cornol, Switzerland and Freyhof, J.: Berlin, Germany, 2007.

- Segherloo, I.H.; Freyhof, J.; Berrebi, P.; Ferchaud, A.-L.; Geiger, M.; Laroche, J.; Levin, B.A.; Normandeau, E.; Bernatchez, L. A genomic perspective on an old question: Salmo trouts or Salmo trutta (Teleostei: Salmonidae)? Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 162, 107204.

- Snoj, A.; Bravničar, J.; Marić, S.; Sušnik Bajec, S.; Benaissa, H.; Schöffmann, J. Nuclear DNA reveals multiple waves of colonisation, reticulate evolution and a large impact of stocking on trout in north-west Africa. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 3389–3405.

- Duméril, A.H.A. Note sur une truite d’Algérie (Salar macrostigma, A. Dum.). C. R. Hebd. Acad. Sci. 1858, 47, 160–162.

- Schöffmann, J. Autochthone Forellen (Salmo trutta L.) in Nordafrika. Österreichs Fischerei 1993, 46, 164–169.

- Bobbio, L.; Cannas, R.; Cau, A.; Deiana, A.M.; Duchi, A.; Gandolfi, G.; Tagliavini, J. Mitochondrial variability in Italian trouts, with particular reference to “macrostigma” populations. In Proceedings of the 6th National Conference of AIIAD (Associazione Italiana Ittiologi Acque Dolci): Carte Ittiche Dieci Anni Dopo, Varese Ligure, Italy, 6–8 June 1996; pp. 42–49.

- Duchi, A. Flank spot number and its significance for systematics, taxonomy and conservation of the near-threatened Mediterranean trout Salmo cettii: Evidence from a genetically pure population. J. Fish Biol. 2017, 92, 254–260.

- Duchi, A. Extant because important or important because extant? On the scientific importance and conservation of a genetically pure Sicilian population of the threatened Salmo cettii Rafinesque, 1810. Cybium 2020, 44, 41–44.

- Tougard, C.; Justy, F.; Guinand, B.; Douzery, E.J.P.; Berrebi, P. Salmo macrostigma (Teleostei, Salmonidae): Nothing more than a brown trout (S. trutta) lineage? J. Fish Biol. 2018, 93, 302–310.

- Splendiani, A.; Palmas, F.; Sabatini, A.; Caputo Barucchi, V. The name of the trout: Considerations on the taxonomic status of the Salmo trutta L., 1758 complex (Osteichthyes: Salmonidae) in Italy. Eur. Zool. J. 2019, 86, 432–442.

- Fruciano, C.; Pappalardo, A.M.; Tigano, C.; Ferrito, V. Phylogeographical relationships of Sicilian brown trout and the effects of genetic introgression on morphospace occupation. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2014, 112, 387–398.

- Rafinesque-Schmaltz, C.S. Indice d’Ittiologia Siciliana: Ossia, Catalogo Metodico dei Nomi Latini, Italiani, e Siciliani dei Pesci, che si Rinvengono in Sicilia Disposti Secondo un Metodo Naturale e Seguito da un Appendice che Contiene la Descrizione de Alcuni Nuovi Pesci Siciliani; del Nobolo G: Messina, Italy, 1810.

- Duchi, A.; (Legambiente Ragusa, Ragusa, Italy). Personal communication, 2021.

- Giuffra, E. Identificazione Genetica e Filogenia delle Popolazioni di Trota Comune, Salmo trutta L., del Bacino del Po. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Turin, Turin, Italy, 1993.

- Giuffra, E.; Guyomard, R.; Forneris, G. Phylogenetic relationships and introgression patterns between incipient parapatric species of Italian brown trout (Salmo trutta L. complex). Mol. Ecol. 1996, 5, 207–220.

- Meraner, A.; Gandolfi, A. Genetics of the genus Salmo in Italy: Evolutionary history, population structure, molecular ecology and conservation. In Brown Trout: Biology, Ecology and Management; Lobón-Cerviá, J., Sanz, N., Eds.; Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 65–102.

- Giuffra, E.; Bernatchez, L.; Guyomard, R. Mitochondrial control region and protein coding gene sequence variation among phenotypic forms of brown trout Salmo trutta from Northern Italy. Mol. Ecol. 1994, 3, 161–172.

- Patarnello, T.; Bargelloni, L.; Caldara, F.; Colombo, L. Cytochrome b and 16S rRNA sequence variation in the Salmo trutta (Salmonidae, Teleostei) species complex. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1994, 3, 69–74.

- Gratton, P.; Allegrucci, G.; Gandolfi, A.; Sbordoni, V. Genetic differentiation and hybridization in two naturally occurring sympatric trout Salmo spp. forms from a small karstic lake. J. Fish Biol. 2013, 82, 637–657.

- Gratton, P.; Allegrucci, G.; Sbordoni, V.; Gandolfi, A. The evolutionary jigsaw puzzle of the surviving trout (Salmo trutta L. complex) diversity in the Italian region. A multilocus Bayesian approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014, 79, 292–304.

- Palombo, V.; De Zio, E.; Salvatore, G.; Esposito, S.; Iaffaldano, N.; D’Andrea, M. Genotyping of two Mediterranean trout populations in central-southern Italy for conservation purposes using a rainbow-trout-derived SNP array. Animals 2021, 11, 1803.

- Karaman, S. Prilog poznavanju slatkovodnih riba Jugoslavije. Glasnik Skopskog naučnog društva knj. Skopje 1938, 18, 131–139.

- Bianco, P.G. An update on the status of native and exotic freshwater fishes of Italy. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014, 30, 62–77.

- Chiereghin, S. Descrizione de’ Pesci, de’ Crostacei e de’ Testacei che Abitano le Lagune ed il Golfo Veneto; Canova ed: Treviso, Italy, 2001; Volume 2.

- Soldo, A. First marine record of marble trout Salmo marmoratus. J. Fish Biol. 2013, 82, 700–702.

- Snoj, A.; Marčeta, B.; Sušnik, S.; Melkič, E.; Meglič, V.; Dovč, P. The taxonomic status of the ’sea trout’ from the north Adriatic Sea, as revealed by mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analysis. J. Biogeogr. 2002, 29, 1179–1185.

- Splendiani, A.; Ruggeri, P.; Giovannotti, M.; Caputo Barucchi, V. Role of environmental factors in the spread of domestic trout in Mediterranean streams. Freshwat. Biol. 2013, 58, 2089–2101.

- Borroni, I.; Grimaldi, E. Fattori e tendenze di modificazione dell’ittiofauna italiana d’acqua dolce. Ital. J. Zool. 1978, 45, 63–73.

- Bianco, P.G.; Delmastro, G.B. Recenti novità tassonomiche riguardanti i pesci d’acqua dolce autoctoni in Italia e descrizione di una nuova specie di luccio. Res. Wildl. Conserv. 2011, 2, 1–14.

- Gridelli, E. I Pesci d’Acqua Dolce della Venezia Giulia; Del Bianco D.: Udine, Italy, 1935.

- Old Maps Online. Available online: https://www.oldmapsonline.org/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Splendiani, A.; Berrebi, P.; Tougard, C.; Righi, T.; Reynaud, N.; Fioravanti, T.; Lo Conte, P.; Delmastro, G.B.; Baltieri, M.; Ciuffardi, L.; et al. The role of the south-western Alps as a unidirectional corridor for Mediterranean brown trout (Salmo trutta complex) lineages. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2020, 131, 909–926.

- Rossi, A.R.; Petrosino, G.; Milana, V.; Martinoli, M.; Rakaj, A.; Tancioni, L. Genetic identification of native populations of Mediterranean brown trout Salmo trutta L. complex (Osteichthyes: Salmonidae) in central Italy. Eur. Zool. J. 2019, 86, 424–431.

- Zanetti, M.; Nonnis Marzano, F.; Lorenzoni, M. I Salmonidi Italiani: Linee Guida per la Conservazione della Biodiversità. 2013, A.I.I.A.D. (Associazione Italiana Ittiologi Acque Dolci) Gruppo di Lavoro Salmonidi. Available online: http://www.aiiad.it/sito/temi/salmonidi/24-documento-salmonidi-febbraio-2013 (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Lorenzoni, M. The check-list of the Italian freshwater fish fauna. Ital. J. Freshwat. Ichthyol. 2019, 5, 239–254.

- Pustovrh, G.; Sušnik Bajec, S.; Snoj, A. Evolutionary relationship between marble trout of the northern and the southern Adriatic basin. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2011, 59, 761–766.

- Pustovrh, G.; Snoj, A.; Bajec, S.S. Molecular phylogeny of Salmo of the western Balkans, based upon multiple nuclear loci. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2014, 47, 7.

- Lecaudey, L.A.; Schliewen, U.K.; Osinov, A.G.; Taylor, E.B.; Bernatchez, L.; Weiss, S.J. Inferring phylogenetic structure, hybridization and divergence times within Salmoninae (Teleostei: Salmonidae) using RAD-sequencing. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2018, 124, 82–99.

- Bernatchez, L.; Guyomard, R.; Bonhomme, F. DNA sequence variation of the mitochondrial control region among geographically and morphologically remote European brown trout Salmo trutta populations. Mol. Ecol. 1992, 1, 161–173.

- Berrebi, B.; Povz, B.; Jesensek, D.; Cattaneo-Berrebi, G.; Crivelli, A.J. The genetic diversity of native, stocked and hybrid populations of marble trout in the Soca River, Slovenia. Heredity 2000, 85, 277–287.

- Bernatchez, L. The evolutionary history of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) inferred from phylogeographic, nested clade, and mismatch analyses of mitochondrial DNA variation. Evolution 2001, 55, 351–379.

- Sanz, N. Phylogeographic history of brown trout: A review. In Brown Trout: Biology, Ecology and Management; Lobón-Cerviá, J., Sanz, N., Eds.; Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 17–64.

- Lobón-Cerviá, J.; Esteve, M.; Berrebi, P.; Duchi, A.; Lorenzoni, M.; Young, K.A. Trout and char of central and southern Europe and northern Africa. In Trout and Char of the World; Kershner, J.L., Williams, J.E., Gresswell, R.E., Lobón-Cerviá, J., Eds.; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2019; pp. 379–410.

- Maddison, W.P. Gene trees in species trees. Syst. Biol. 1997, 46, 523–536.

- Sušnik Bajec, S.; Pustovhr, G.; Jasenšek, D.; Snoj, A. Population genetic SNP analysis of marble and brown trout in a hybridization zone of the Adriatic watershed in Slovenia. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 184, 239–250.

- Snoj, A.; Marić, S.; Berrebi, P.; Crivelli, A.J.; Shumka, S.; Sušnik, S. Genetic architecture of trout from Albania as revealed by mtDNA control region variation. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2009, 41, 22.

- Bianco, P.G. Potential role of the paleohistory of the Mediterranean and Paratethys basins on the early dispersal of Auro-Mediterranean freshwater fishes. Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwat. 1990, 1, 167–184.

- Meraner, A.; Baric, S.; Pelster, B.; Dalla Via, J. Trout (Salmo trutta) mitochondrial DNA polymorphism in the centre of the marble trout distribution area. Hydrobiologia 2007, 579, 337–349.

- Pujolar, J.M.; Lucarda, A.N.; Simonato, M.; Patarnello, T. Restricted gene flow at the micro- and macro-geographical scale in marble trout based on mtDNA and microsatellite polymorphism. Front. Zool. 2011, 8, 1–10.

- Lucarda, A.N.; Bargelloni, L.; Patarnello, T.; Gandolfi, G. Genetic characterisation of Salmo trutta marmoratus (Cuvier, 1817) populations by means of nuclear markers: Preliminary results. Quad. ETP 1999, 28, 1–5.

- Meraner, A.; Baric, S.; Pelster, B.; Dalla Via, J. Microsatellite DNA data point to extensive but incomplete admixture in a marble and brown trout hybridization zone. Conserv. Genet. 2010, 11, 985–998.

- Marazzi, S. Atlante Orografico delle Alpi. SOIUSA: Suddivisione Orografica Internazionale Unificata del Sistema Alpino; Priuli & Verlucca: Pavone Canavese, Italy, 2005.

- Meraner, A.; Gratton, P.; Baraldi, F.; Gandolfi, A. Nothing but a trace left? Autochthony and conservation status of Northern Adriatic Salmo trutta inferred from PCR multiplexing, mtDNA control region sequencing and microsatellite analysis. Hydrobiologia 2013, 702, 201–213.

- Splendiani, A.; Ruggeri, P.; Giovannotti, M.; Pesaresi, S.; Occhipinti, G.; Fioravanti, T.; Lorenzoni, M.; Nisi Cerioni, P.; Caputo Barucchi, V. Alien brown trout invasion of the Italian peninsula: The role of geological, climate and anthropogenic factors. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 2029–2044.

- Splendiani, A.; Fioravanti, T.; Giovannotti, M.; Olivieri, L.; Ruggeri, P.; Nisi Cerioni, P.; Vanni, S.; Enrichetti, F.; Caputo Barucchi, V. Museum samples could help to reconstruct the original distribution of Salmo trutta complex in Italy. J. Fish Biol. 2017, 90, 2443–2451.

- Casalis, G. Dizionario Geografico Storico-Statistico-Commerciale degli Stati di S.M. il Re di Sardegna; Maspero: Turin, Italy, 1833; Volume 1.

- Casalis, G. Dizionario Storico-Statistico-Commerciale degli Stati di S.M. il Re di Sardegna; Maspero: Turin, Italy, 1852; Volume 22.

- Festa, E. I pesci del Piemonte. Boll. Mus. Zool. Anat. Comp. R Univ. Torino 1892, 7, 1–125.

- Von Siebold, C.T.E. Ueber die Fische des Ober-Engadins. In Proceedings of the Verhandlungen der Schweizerischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft zu Samaden, Samaden, Switzerland, 24–26 August 1863; pp. 173–190.

- Monti, M. Notizie dei Pesci delle Provincie di Como e Sondrio e del Cantone Ticino; Franchi, C.: Como, Italy, 1864.

- Fatio, V. Faune des Vertébrés de la Suisse: Histoire Naturelle des Poissons; II part; Georg, H.: Geneva, Switzerland; Basel, Switzerland, 1890; Volume 5, pp. 354–355.

- Sommani, E. Il Salmo marmoratus CUV.: Sua origine e distribuzione nell’Italia settentrionale. Boll. Pesca Piscic. E Idrobiol. 1960, 15, 40–47.

- Schönswetter, P.; Stehlik, I.; Holderegger, R.; Tribsch, A. Molecular evidence for glacial refugia of mountain plants in the European Alps. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 3547–3555.

- Stefani, F.; Anzani, A.; Marieni, A. Echoes from the past: A genetic trace of native brown trout in the Italian Alps. Environ. Biol. Fish 2020, 102, 1327–1335.

- Schorr, G.; Holstein, N.; Pearman, P.B.; Guisan, A.; Kadereit, J.W. Integrating species distribution models (SDMs) and phylogeography for two species of Alpine Primula. Ecol. Evol. 2012, 2, 1260–1277.

- D’Ancona, I.J.; Merlo, S. La speciazione delle trote italiane ed in particolare in quelle del lago di Garda. Atti. Lst. Ven. Sci. Lett. Arti. 1959, 117, 19–26.

- Behnke, R.J. The systematics of salmonid fishes of recently glaciated lakes. J. Fish Res. Board Can. 1972, 29, 639–671.

- Todesco, M.; Pascual, M.A.; Owens, G.L.; Ostevik, K.; Moyers, B.T.; Hubner, S.; Heredia, S.M.; Hahn, M.A.; Caseys, C.; Bock, D.G.; et al. Hybridization and extinction. Evol. Appl. 2016, 9, 892–908.

- Meldgaard, T.; Crivelli, A.J.; Jesensek, D.; Poizat, G.; Rubin, J.-F.; Berrebi, P. Hybridization mechanisms between the endangered marble trout (Salmo marmoratus) and the brown trout (Salmo trutta) as revealed by in-stream experiments. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 136, 602–611.

- Hamilton, K.E.; Ferguson, A.; Taggart, J.B.; Tómasson, T.; Walker, A.; Fahy, E. Post-glacial colonization of brown trout, Salmo trutta L.: Ldh-5* as a phylogeographic marker locus. J. Fish Biol. 1989, 35, 651–664.

- Presa, P.; Krieg, F.; Estoup, A.; Guyomard, R. Diversité et gestion génétique de la truite commune: Apport de I’étude du polymorphisme des locus protéiques et microsatellites. Gén. Sél. Evol. 1994, 26 (Suppl. S1), 183s–202s. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00894063 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Largiadèr, C.R.; Scholl, A. Effects of stocking on the genetic diversity of brown trout populations of the Adriatic and Danubian drainages in Switzerland. J. Fish Biol. 1995, 47 (Suppl. A), 209–255.

- Sommani, E. Sulla presenza del Salmo fario (L.) e del Salmo marmoratus (Cuv.) nell’Italia settentrionale: Loro caratteristiche ecologiche e considerazioni relative ai ripopolamenti. Boll. Pesca Piscic. Idrobiol. 1948, 3, 136–145.

- Keller, I.; Taverna, A.; Seehausen, O. Evidence of neutral and adaptive genetic divergence between European trout populations sampled along altitudinal gradients. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 1888–1904.

- Keller, I.; Schuler, J.; Bezault, E.; Seehausen, O. Parallel divergent adaptation along replicated altitudinal gradients in Alpine trout. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 210.

- Analisi dell’opera. Natura Morta con Pesci di Evaristo Baschenis. Natura Morta con Pesci, ~1670, oil on Canvas, 65 cm × 108 cm. Bergamo, Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara. Available online: https://www.analisidellopera.it/natura-morta-con-pesci-baschenis/ (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Bianco, P.G. Freshwater fish transfers in Italy: History, local modification of fish composition, and a prediction on the future of native populations. In Stocking and Introductions of Fishes; Cowx, I.G., Ed.; Fishing New Book; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 167–185.

- Sacchi, B. (Platina) Platine de Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine; de Aquila, L.: Venice, Italy, 1475.

- Giovio, P. Novocomensis de Piscibus Marinis, Lacustribus, Fluviatilibus, Item de Testaceis ac Salsamentis Liber; Minitii Calvi, F.: Rome, Italy, 1527.

- Salviani, I. Aquatilium Animalium Historiae, Liber Primus: Cum Eorumdem Formis, Aere Excusis; Saluianum: Rome, Italy, 1554.

- Porcacchi, T.; Giolito de Ferrari, G.; Gesuiti: Collegio, R. La Nobiltà della Città di Como Descritta da Thomaso Porcacchi da Castiglione Arretino: Con la Tavola delle Cose Notabili; di Ferrarii Giolito, G.: Venice, Italy, 1569.

- Scappi, B. Opera di Bartolomeo Scappi, Mastro Dell’arte del Cucinare, Divisa in Sei Libri; de’ Vecchi, A.: Venice, Italy, 1570.

- Grattarolo, B. Historia della Riviera di Salò; Sabbio, V.: Brescia, Italy, 1599.

- Stefani, B. L’arte di Ben Cucinare, et Instruire i Men Periti in Questa Lodevole Professione: Dove Anco s’Insegna a Far Pasticci, Sapori, Salse, Gelatine, Torte, et Altro; Osanna: Mantua, Italy, 1662.

- Roberti, G. Lettera Sopra il Canto de’ Pesci; della Volpe, L.: Bologna, Italy, 1767.

- Delling, B. Morphological distinction of the marble trout, Salmo marmoratus, in comparison to marbled Salmo trutta from River Otra, Norway. Cybium 2002, 26, 283–300.

- Snoj, A.; Glamuzina, B.; Razpet, A.; Zablocki, J.; Bogut, I.; Lerceteau-Köhler, E.; Pojskić, N.; Sušnik, S. Resolving taxonomic uncertainties using molecular systematics: Salmo dentex and the Balkan trout community. Hydrobiologia 2010, 651, 199–212.

- Pontalti, L. La trota marmorata dai fiumi ai ruscelli: Possibilità, per una specie in pericolo, di allungare il proprio habitat. Seconda parte: Acclimatamento di una popolazione. Dendronatura 2020, 1, 76–83.

- Huitfeldt-Kaas, H. Ferskvandsfiskenes Utbredelse og Indvandring i Norge; Central Trykkeriet: Oslo, Norway, 1918.

- Sønstebø, J.H.; Borgstrøm, R.; Heun, M. Genetic structure of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) from the Hardangervidda mountain plateau (Norway) analyzed by microsatellite DNA: A basis for conservation guidelines. Conserv. Genet. 2007, 8, 33–44.

- Miró, A.; Ventura, M. Evidence of exotic trout mediated minnow invasion in Pyrenean high mountain lakes. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 791–803.

- Tiberti, R.; Splendiani, A. Management of a highly unlikely native fish: The case of arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus from the Southern Alps. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshwat. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 312–320.

- Vilizzi, L. The common carp, Cyprinus carpio, in the Mediterranean region: Origin, distribution, economic benefits, impacts and management. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2011, 19, 93–110.