Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cecilia Cheng | -- | 1442 | 2022-04-22 13:12:27 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1442 | 2022-04-24 04:47:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Cheng, C.; , . Social Media Addiction during COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22169 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Cheng C, . Social Media Addiction during COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22169. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Cheng, Cecilia, . "Social Media Addiction during COVID-19" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22169 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Cheng, C., & , . (2022, April 22). Social Media Addiction during COVID-19. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22169

Cheng, Cecilia and . "Social Media Addiction during COVID-19." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

In the early stages of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, national lockdowns and stay-at-home orders were implemented by many countries to curb the rate of infection. An extended stay-at-home period can frustrate people’s need for relatedness, with many turning to social media to interact with others in the outside world. However, social media use may be maladaptive due to its associations with social media addiction and psychosocial problems.

information technology addiction

mental health

psychological need

social distancing

social media

social networking site

social media addiction

psychological symptoms

mental wellness

epidemic

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by an unknown highly transmissible virus [1][2]. This novel disease quickly escalated into a global pandemic that has affected more than 325 million people and caused approximately 5.5 million deaths worldwide as of 15 January 2022 [3]. To mitigate the rapid spread of the COVID-19 infection in the pandemic’s early stages, many countries implemented the drastic public health control measures of national lockdowns or stay-at-home orders [4][5][6][7]. Depression and loneliness were the two “signature mental health concerns” during the COVID-19 era [8][9][10][11].

The residents of countries with stay-at-home orders in effect could not maintain contact with others through face-to-face interactions. A recent meta-analysis revealed social isolation to be consistently associated with both mental and physical health problems [12], although most of the studies included in the meta-analysis investigated subjective rather than objective social isolation. The present entry extends the literature by examining objective social isolation; actually, such isolation was mandatory due to the implementation of stay-at-home orders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Prevalence of Social Media Addiction during COVID-19 Pandemic

In the present cyber era, people interact with others in two worlds: the real and the cyber worlds. With face-to-face interactions restricted under a national lockdown or stay-at-home orders, social media emerged as a major means of connecting with social network members [13][14]. A previous study revealed time spent with family members and friends to be inversely associated with internet use [15]. It is not surprising that Facebook, one of the most commonly used social media platforms, has reported a 70% increase in time spent on the platform and more than a 50% increase in messaging since the onset of the pandemic [16]. As the mandated physical distancing measures deprived individuals of opportunities to connect with their social network members in person, many of them turned to social media to maintain existing offline relations via online platforms [17][18][19][20].

The optimal use of social media has been found to foster psychological well-being through the development of new social relations and the strengthening of existing ties [21][22][23]. However, social media use should only be regarded as a supplement to face-to-face interactions rather than a surrogate for social connections in real life or a replacement for a loss of real-life social support [24]. Such a notion stems from a study that compared the levels of life satisfaction among social media, phone, and in-person communication [25]. The findings indicate that highly active users tend to experience a reduction in levels of life satisfaction after using social media, whereas both in-person and phone interactions are positively associated with life satisfaction.

Apart from exerting immediate undesirable effects, excessive use of social media has also been found to incur more long-term maladaptive consequences, with social media addiction as the most common type of such problems. Social media addiction refers to a type of behavioural addiction characterized by an over-concern about using social media and an uncontrollable urge to log on to or use social media [26][27]. Individuals with social media addiction are characterized by an array of symptoms, including a preoccupation with using social media, the development of tolerance symptoms, and a failure to stop using social media despite experiencing adverse consequences [7][28]. Such a devotion of abundant time and effort to social media use has been found to impair functioning in important life domains, especially interpersonal relations [26][29]. In addition, a myriad of studies have documented positive associations between social media addiction and a range of psychosocial problems [30][31][32][33]. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, social media addiction has been found to be prevalent across countries [28][34][35][36] and across social media platforms [35].

3. Relatedness Needs as Behavioural Motives and Experiential Requirements

The implementation of the unprecedented stay-at-home orders also disrupted certain fundamental needs, especially those related to social interactions. According to the basic psychological needs theory, one of the subsidiary theories of the self-determination theory [37], the foundation of mental health is the gratification of three basic needs, two of which are personal (needs for autonomy and competence) and the other of which is social (need for relatedness) in nature. Espousing a nuanced view, the two-process model of psychological needs further decomposes basic needs into two elements: need frustration and need satisfaction [38][39]. These two elements of basic needs play distinct roles: needs-as-motives and needs-as-requirements. Specifically, need frustration operates as an underlying motivation that drives and guides individuals to engage in certain behaviours (needs-as-motives), whereas need satisfaction serves as an experiential condition derived from the individuals’ antecedent behaviours (needs-as-requirements).

Of the three fundamental needs highlighted in this theory, relatedness need was considered most likely to influence mental wellness in the context of COVID-19-mandated physical distancing. Relatedness need refers to the desire to be connected to and maintain optimal relations with others [37]. As social animals, human beings have a strong need to belong and affiliate with other people [40]. However, when the stay-at-home orders were in place, the relatedness needs of the residents in the affected regions could not be gratified. As mentioned at the outset, many of the residents turned to social media in an attempt to gain social compensation, and social media addiction was common during the lockdown period in many countries [28][34][35][36]. The constructs of relatedness need frustration and relatedness need satisfaction as well as their respective functions may shed light on individual differences in susceptibility to social media addiction.

3.1. Relatedness Needs as Behavioural Motives of Social Media Addiction

From the perspective of the classic theories of motivation [41][42], relatedness need can be viewed as an underlying motivation that drives individuals to engage in certain behaviours and guides their subsequent actions (needs-as-motives). If individuals’ relatedness needs in the real-life social environment are thwarted, they are motivated to seek compensation through interacting with others on social media platforms [43][44]. Empirical data have supported this notion by revealing that social media addiction was positively associated with relatedness need frustration [45]. In addition, previous studies have documented the intervention roles of social media addiction and relatedness need satisfaction in improving mental health problems, particularly depressive symptoms and loneliness [46][47][48][49].

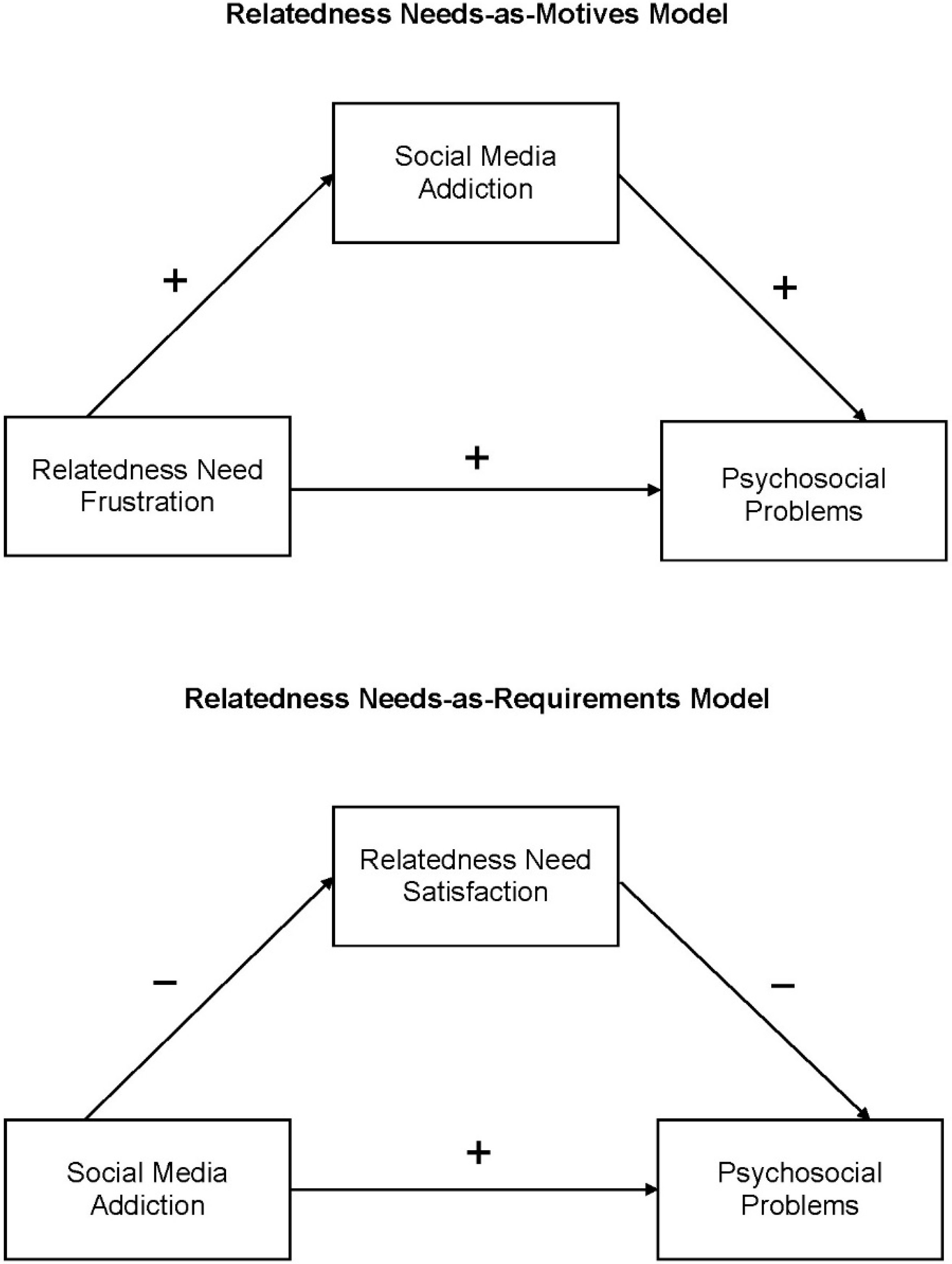

In light of these theoretical postulations and empirical findings, a relatedness needs-as-motives model was formulated, and a set of hypotheses derived from this model is summarized in the upper panel of Figure 1. As similar tendencies of heavy use of social media and social media addiction prevalence were observed during COVID-19-mandated physical distancing, this entry was set in this specific context to evaluate the empirical validity of the relatedness needs-as-motives model through testing the following hypotheses:

Figure 1. Conceptual frameworks of the relatedness needs-as-motives and the relatedness needs-as-requirements models.

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Relatedness need frustration is positively associated with psychosocial problems (i.e., depressive symptoms and loneliness).

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Relatedness need frustration is positively associated with social media addiction.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Social media addiction is positively associated with psychosocial problems.

Hypothesis 4 (H4):

Social media addiction mediates the positive association between relatedness need frustration and psychosocial problems (relatedness needs-as-motives model).

3.2. Relatedness Needs as Experiential Requirements of Social Media Addiction

For the basic psychological needs theory, a major tenet is that basic needs are “psychological nutrients” that are crucial for psychological adjustment and personal growth [50]. As mentioned above, individuals are motivated to engage in social media to compensate for a perceived loss in the social support that was originally rendered through face-to-face interactions; such attempts of social compensation seeking are largely futile [21]. Similar to other types of behavioural addiction, such as internet gaming addiction [51], social media addiction has been consistently found to be positively associated with problems in romantic and other social relations [52][53], resulting in attachment anxiety, relational ambivalence, and relational dissatisfaction [54][55]. Furthermore, the failure to gratify relatedness needs has been found to be associated with psychosocial problems [56][57]. In light of these theoretical postulations and empirical findings, a relatedness needs-as-requirements model was formulated, and a set of hypotheses derived from this model is shown in the lower panel of Figure 1. Another aim of the present entry was to evaluate the empirical validity of this model in the pandemic context through testing the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Social media addiction is negatively associated with relatedness need satisfaction.

Hypothesis 6 (H6):

Relatedness need satisfaction is negatively associated with psychosocial problems.

Hypothesis 7 (H7):

Relatedness need satisfaction mediates the positive association between social media addiction and psychosocial problems (relatedness needs-as-requirements model).

References

- Zhao, S.; Lin, Q.; Ran, J.; Musa, S.S.; Yang, G.; Wang, W.; Lou, Y.; Gao, D.; Yang, L.; He, D.; et al. Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: A data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 92, 214–217.

- Rothan, H.A.; Byrareddy, S.N. The epidemiology and pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 109, 102433.

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Cheng, C.; Wang, H.-Y.; Chau, C.-L. Mental health issues and health disparities amid COVID-19 outbreak in China: Comparison of residents inside and outside the epicenter. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 303, 114070.

- Pancani, L.; Marinucci, M.; Aureli, N.; Riva, P. Forced social isolation and mental health: A study on 1006 Italians under COVID-19 lockdown. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1540.

- Salazar, A.; Palomo-Osuna, J.; de Sola, H.; Moral-Munoz, J.A.; Dueñas, M.; Failde, I. Psychological impact of the lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic in university workers: Factors related to stress, anxiety, and depression. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4367.

- Cheng, C.; Ebrahimi, O.V.; Luk, J.W. Heterogeneity of prevalence of social media addiction across multiple classification schemes: Latent profile analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e27000.

- Killgore, W.D.S.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Dailey, N.S. Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 290, 113117.

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57.

- Li, L.Z.; Wang, S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 291, 113267.

- Bueno-Notivol, J.; Gracia-García, P.; Olaya, B.; Lasheras, I.; López-Antón, R.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2021, 21, 100196.

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171.

- Burhamah, W.; AlKhayyat, A.; Oroszlányová, M.; AlKenane, A.; Almansouri, A.; Behbehani, M.; Karimi, N.; Jafar, H.; AlSuwaidan, M. The psychological burden of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown measures: Experience from 4000 participants. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 977–985.

- Brailovskaia, J.; Ozimek, P.; Bierhoff, H.-W. How to prevent side effects of social media use (SMU)? Relationship between daily stress, online social support, physical activity and addictive tendencies—A longitudinal approach before and during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Germany. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021, 5, 100144.

- Nie, N.H.; Hillygus, D.S. The impact of Internet use on sociability: Time-diary findings. IT Soc. 2002, 1, 1–20.

- Schultz, A. Keeping Our Services Stable and Reliable during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Available online: https://about.fb.com/news/2020/03/keeping-our-apps-stable-during-covid-19/ (accessed on 16 July 2020).

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. The relationship between burden caused by coronavirus (COVID-19), addictive social media use, sense of control and anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106720.

- Zhang, M.X.; Chen, J.H.; Tong, K.K.; Yu, E.W.; Wu, A.M.S. Problematic smartphone use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Its as-sociation with pandemic-related and generalized beliefs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5724.

- Yue, Z.; Lee, D.S.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, R. Social media use, psychological well-being and physical health during lockdown. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2021, 1–18.

- Baraybar-Fernández, A.; Arrufat-Martín, S.; Rubira-García, R. Public Information, Traditional Media and Social Networks during the COVID-19 Crisis in Spain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6534.

- Cheng, C.; Wang, H.; Sigerson, L.; Chau, C. Do socially rich get richer? A nuanced perspective on social network site use and online social capital accrual. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 734–764.

- Piedra, J. Redes sociales en tiempos del COVID-19: El caso de la actividad física. Sociol. Del Deporte 2020, 1, 41–43.

- Alférez, N.P. Las redes sociales y la COVID-19: Herramientas para la infodemia. Bol. IEEE 2020, 20, 831–853.

- Chan, M.S.; Cheng, C. Explaining personality and contextual differences in beneficial role of online versus offline social support: A moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 747–756.

- Kross, E.; Verduyn, P.; Demiralp, E.; Park, J.; Lee, D.S.; Lin, N.; Shablack, H.; Jonides, J.; Ybarra, O. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69841.

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S. Social network site addiction-An overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4053–4061.

- Tutgun-Ünal, A. Social media addiction of new media and journalism students. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 2020, 19, 1–12.

- Wartberg, L.; Kriston, L.; Thomasius, R. Internet gaming disorder and problematic social media use in a representative sample of German adolescents: Prevalence estimates, comorbid depressive symptoms and related psychosocial aspects. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 103, 31–36.

- Ahmed, O.; Nayeem Siddiqua, S.J.; Alam, N.; Griffiths, M.D. The mediating role of problematic social media use in the relationship between social avoidance/distress and self-esteem. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101485.

- Boursier, V.; Gioia, F.; Griffiths, M.D. Do selfie-expectancies and social appearance anxiety predict adolescents’ problematic social media use? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106395.

- Cheng, C.; Lau, Y.; Chan, L.; Luk, J.W. Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106845.

- Fabris, M.A.; Marengo, D.; Longobardi, C.; Settanni, M. Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addict. Behav. 2020, 106, 106364.

- Gong, R.; Zhang, Y.; Long, R.; Zhu, R.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Cai, Y. The impact of social network site addiction on depression in Chinese medical students: A serial multiple mediator model involving loneliness and unmet interpersonal needs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8614.

- Luo, T.; Chen, W.; Liao, Y. Social media use in China before and during COVID-19: Preliminary results from an online retrospective survey. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 140, 35–38.

- Marengo, D.; Angelo Fabris, M.; Longobardi, C.; Settanni, M. Smartphone and social media use contributed to individual tendencies towards social media addiction in Italian adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Addict. Behav. 2022, 126, 107204.

- Panno, A.; Carbone, G.A.; Massullo, C.; Farina, B.; Imperatori, C. COVID-19 related distress is associated with alcohol problems, social media and food addiction symptoms: Insights from the Italian experience during the lockdown. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 577135.

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In Handbook of Self-Determination Research; Deci, E.L., Ryan, R.M., Eds.; University of Rochester: Rochester, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 3–33.

- Prentice, M.; Halusic, M.; Sheldon, K.M. Integrating theories of psychological needs-as-requirements and psychological needs-as-motives: A two process model. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2014, 8, 73–85.

- Sheldon, K.M. Integrating behavioral-motive and experiential-requirement perspectives on psychological needs: A two process model. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 118, 552.

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529.

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1970.

- Murray, H. Explorations in Personality; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1938.

- Poley, M.E.M.; Luo, S. Social compensation or rich-get-richer? The role of social competence in college students’ use of the internet to find a partner. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 414–419.

- Zywica, J.; Danowski, J. The faces of Facebookers: Investigating social enhancement and social compensation hypotheses; predicting Facebook™ and offline popularity from sociability and self-esteem, and mapping the meanings of popularity with semantic networks. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2008, 14, 1–34.

- Sheldon, K.M.; Abad, N.; Hinsch, C. A two-process view of Facebook use and relatedness need-satisfaction: Disconnection drives use, and connection rewards it. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 766–775.

- Li, A.Y.; Chau, C.; Cheng, C. Development and validation of a parent-based program for preventing gaming disorder: The Game Over Intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1984.

- Hou, Y.; Xiong, D.; Jiang, T.; Song, L.; Wang, Q. Social media addiction: Its impact, mediation, and intervention. Cyberpsychology 2019, 13, 4.

- Fousiani, K.; Dimitropoulou, P.; Michaelides, M.P.; Van Petegem, S. Perceived parenting and adolescent cyber-bullying: Examining the intervening role of autonomy and relatedness need satisfaction, empathic concern and recognition of humanness. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2120–2129.

- Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Pulido-González, J.J.; Leo, F.M.; González-Ponce, I.; García-Calvo, T. Effects of an intervention with teachers in the physical education context: A Self-Determination Theory approach. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189986.

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M. On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2013, 23, 263–280.

- Sigerson, L.; Li, A.Y.L.; Cheung, M.W.L.; Cheng, C. Examining common information technology addictions and their relationships with non-technology-related addictions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 520–526.

- Abbasi, I.S. Social media addiction in romantic relationships: Does user’s age influence vulnerability to social media infidelity? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019, 139, 277–280.

- Abbasi, I.S.; Dibble, J.L. The role of online infidelity behaviors in the link between mental illness and social media intrusion. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2019, 39, 70–83.

- McDaniel, B.T.; Drouin, M.; Cravens, J.D. Do you have anything to hide? Infidelity-related behaviors on social media sites and marital satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 66, 88–95.

- Huang, C. A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 12–33.

- Hong, W.; Liu, R.-D.; Oei, T.-P.; Zhen, R.; Jiang, S.; Sheng, X. The mediating and moderating roles of social anxiety and relatedness need satisfaction on the relationship between shyness and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 301–308.

- Xiao, M.; Wang, Z.; Kong, X.; Ao, X.; Song, J.; Zhang, P. Relatedness need satisfaction and the dark triad: The role of depression and prevention focus. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 677906.

More

Information

Subjects:

Psychology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Entry Collection:

COVID-19

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No