You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inga Zinicovscaia | -- | 2747 | 2022-04-22 10:41:09 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2747 | 2022-04-24 04:03:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Zinicovscaia, I.; , .; Rogatkin, D.; Yushin, N.; Grozdov, D.; Vergel, K. Effect of Nanosilver on Humans. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22161 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

Zinicovscaia I, , Rogatkin D, Yushin N, Grozdov D, Vergel K. Effect of Nanosilver on Humans. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22161. Accessed December 21, 2025.

Zinicovscaia, Inga, , Dmitry Rogatkin, Nikita Yushin, Dmitrii Grozdov, Konstantin Vergel. "Effect of Nanosilver on Humans" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22161 (accessed December 21, 2025).

Zinicovscaia, I., , ., Rogatkin, D., Yushin, N., Grozdov, D., & Vergel, K. (2022, April 22). Effect of Nanosilver on Humans. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22161

Zinicovscaia, Inga, et al. "Effect of Nanosilver on Humans." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Among produced metal nanoparticles, silver nanoparticles are widely used in everyday life products, cosmetics, and medicine. It has already been established that, in nanoscale form, many even inert materials become toxic.

nanoparticles

silver

toxicity

occupational

brain

1. Introduction

Nanoparticles are found in numerous spheres of life. Their application in medicine, food and cosmetic industries, and everyday life is expanding [1]. Due to their unique electrical, optical, chemical, and antimicrobial properties, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) are the most common type of NPs used in consumer products [2]. At the same time, according to publications in toxicology, a wealth of information has already been accumulated confirming that contact with NPs entails serious negative consequences for cells, tissues, and organs, such as the development of oxidative stress, the accumulation of DNA disorders, the induction of apoptosis and inflammation, and the disturbance of the structure and functions of tissues and organs [3][4][5].

Almost every person in the modern world is constantly in contact with NPs, through products or objects containing nanoparticles, or through air, water, and soil. The environment begins to suffer greatly from pollution by various nano-sized substances as a result of emissions from enterprises and vehicle exhaust, sewage discharges, and waste. Due to the widespread use of NPs, including AgNPs, in various industries, employees in the workplace face an increased risk of health problems owing to prolonged (chronic) contact with small doses of NPs that enter the body from the air in contaminated work areas, as well as with water and/or food. Occupational pathology has already accumulated bodies of evidence on the development of diseases caused by NPs in industrial workers, which cannot be explained by other reasons [6][7]. In women of reproductive age employed in industrial fields, contact with NPs is associated with risks for their unborn children due to the ability of NPs to penetrate the placental barrier, which leads to the transfer of NPs from mother to child [8][9].

2. General Toxicity of AgNPs for Cells, Tissues, and Organs

According to numerous publications, the main mechanism of the cellular and molecular toxicity of AgNPs is oxidative stress [10][11]. Thus, 20 nm spherical AgNPs reduced mRNA levels of sodium dismutase 1 and glutathione reductase in male Wistar rats [9]. In the presence of AgNPs, the formation of reactive oxygen species [10], the level of gene expression and the content of antioxidant proteins decrease, and DNA damage [11] increases. The prolonged exposure of adult rats to citrate-stabilized silver NPs at a low dose of 0.2 mg/kg resulted in a decrease in the level of expression of structural proteins, in particular, myelin in myelin sheath cells. AgNPs were also found to increase the body weight and body temperature of animals [12]. The level of developmental regulators (for example, neuronal) also decreases; however, the levels of expression of apoptosis regulators increase; therefore, ultimately, the cell often undergoes apoptosis. At the tissue level, inflammation, swelling, and, as an extreme outcome, necrosis, can develop [13]. In zebrafish, AgNPs caused a decrease in brain and muscle acetylcholinesterase activity, as well as in liver and gill catalase activity. Contact with AgNPs also led to morphological changes such as the fusion of secondary lamellae, curvature, dilated marginal channel, and epithelial lifting [14]. The administration of male CD-1 mice with AgNPs of 10 nm size, compared with NPs with a size of 40 and 100 nm, resulted in overt hepatobiliary toxicity [15].

Some reports indicate that AgNPs are genotoxic and mutagenic, and the degree of their impact directly depends on the dose of NPs and inversely depends on their size [16][17][18]. After exposure of BEAS-2B cells to AgNPs of different primary particle sizes (10, 40, and 75 nm), a cytotoxic effect was observed only at a particle size of 10 nm [19]. The same finding was reported in [20]. Coating agents used to stabilize NPs in a solution can also affect general toxicity, including genotoxicity. For example, AgNPs coated with citrate had more noticeable toxic effects on L5718Y cells than those coated with polyvinylpyrrolidone [21]. The study by Recordati et al. [15] showed that the coating of NPs had no relevant impact on animals. Citrate-coated silver nanopowder was toxic to human skin HaCaT keratinocyte cells, whereas polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanoprism or nanoparticle powder did not exhibit any toxic effect [22]. In a study by Gliga et al. [19], the coating-dependent difference in the cytotoxicity of AgNPs was not detected. El Badawy and al. [23] demonstrated a direct correlation between the toxicity of AgNPs and their surface charge. Thus, negatively charged citrate-coated AgNPs were less toxic to microorganisms than positively charged branched polyethyleneimine-coated AgNPs. The low toxicity of citrate-coated AgNPs was observed in comparison with polyvinylpyrrolidone- and gum arabic-coated AgNPs [24].

It should be noted that the results of evaluating the mutagenicity of AgNPs may also depend on the chosen object of study; for example, Prokhorova et al. [25] did not find chromosomal abnormalities in plant cells after exposure to AgNPs. Studying the effect of AgNPs on freshwater invertebrates with different life strategies—namely, Hydra vulgaris, Daphnia carinata, and Paratya australiensis—the authors described Daphnia carinata as the most sensitive species, followed by Paratya australiensis and Hydra vulgaris [26]. Toxic effects of AgNPs on different organisms in the study by Ivask et al. [20] varied by about two orders of magnitude, with the lowest observed for crustaceans and algae and the highest for mammalian cells.

The results of studies of the effects of NPs on the reproductive function and development of animal organisms are also ambiguous and often contradictory. The bulk of studies demonstrated that AgNPs could cause defects in the neurological, cardiovascular, reproductive, and immune systems of the embryos and fetus; however, in some studies, no adverse effect on the development of AgNPs was found, even at high doses [27]. The development of oxidative stress, the occurrence of morphological defects, slowing heart rate, the appearance of pericardial edema, delayed hatching from eggs, and increased mortality were observed in studies on zebrafish embryos exposed to AgNPs [28][29][30]. Morphological changes in the ovary and testis were observed in rat offspring exposed to AgNPs [31]. Developmental exposure to AgNPs results in long-term gut dysbiosis, body fat increase, and neurobehavioral alterations in mouse offspring [32]. At the same time, it should be mentioned that silver ions (Ag+) provoke similar toxic effects at concentrations hundreds of times lower than those applied for AgNPs [29][30]. It was suggested by some authors that the compounds used for NP coating significantly affected the level of AgNP toxicity. Thus, after contact with polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated AgNPs, zebrafish larva did not differ in morphology and behavior from control ones; however, when citrate was used as a coating agent, some disturbances were detected [33]. In a study by González et al. [34], in which the level of AgNPs in solution was close to their environmental concentrations in water (0.03–3 ppm), no negative changes in the survival, hatching, or morphology of Danio rerio were found. According to a number of studies, after a single oral administration, reproductive dysfunctions in males and females (inhibition of spermatogenesis, histopathological disorders in ovaries, etc.) were observed in rodents exposed to AgNPs. It is noteworthy that the smaller the dose and size of AgNPs were, the less pronounced were the effects [35]. Undoubtedly, the dose–response principle also works in nanotoxicology.

3. Effect of AgNPs on the Brain and Behavior

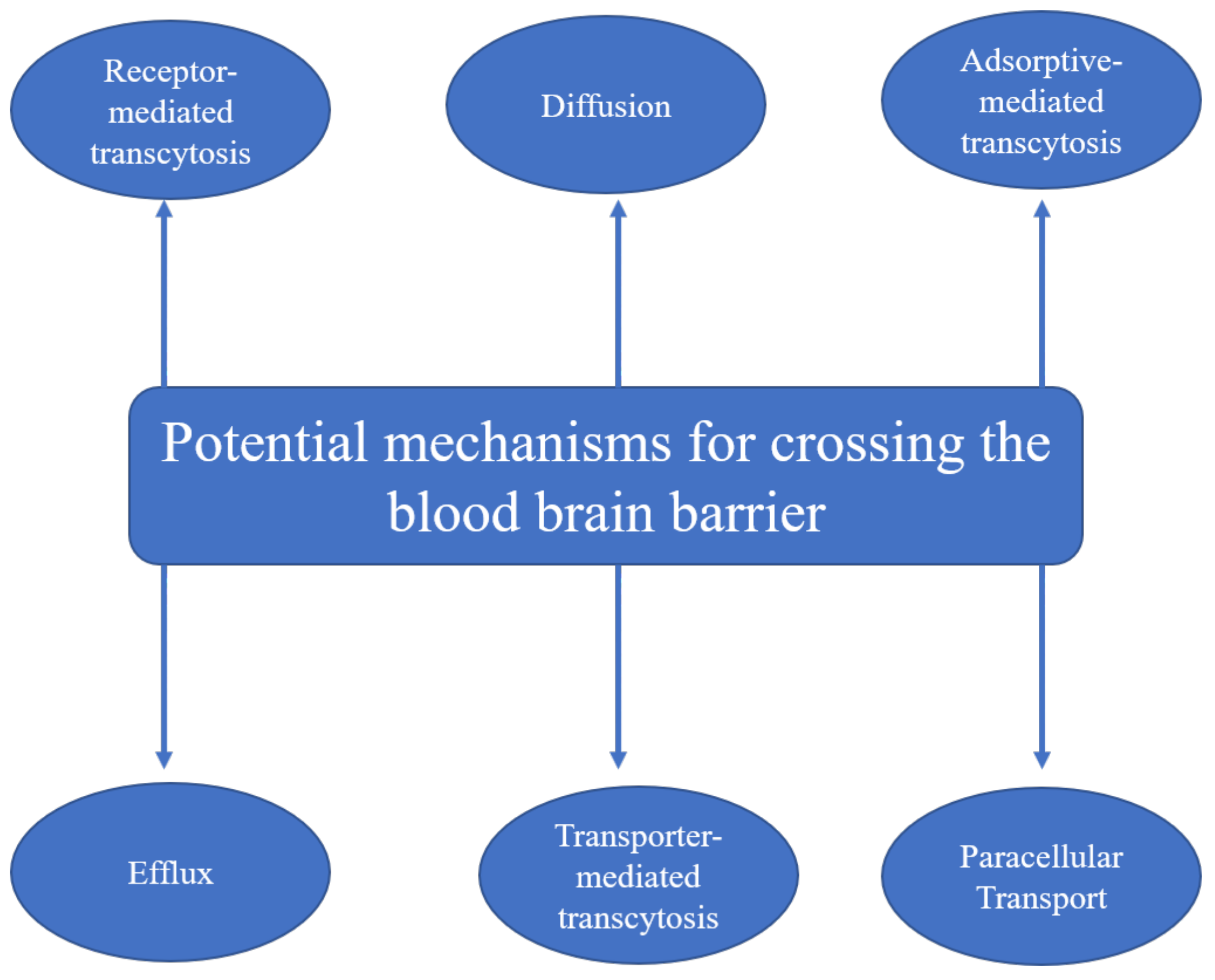

AgNPs along with other metal NPs are able to cross not just the placental barrier but the blood–brain barrier as well [8][9]. Tang et al. [36] proposed two mechanisms of AgNP penetration across the blood–brain barrier, i.e., the transcytosis of endothelial cells of the brain–blood capillary and the reduction in the close connection between endothelial cells, or dissolution of endothelial cell membranes. The main mechanisms of nanoparticles for crossing the blood–brain barrier according to the literature are summarized in Figure 1.

Therefore, upon contact with NPs, there is a risk of biochemical, histological, and functional disorders in the brain, including cognitive dysfunctions. Studies of the effect of NPs on brain functions have received much attention in recent years. After a single dose injection of AgNPs, the parameters of oxidative stress and the antioxidant potential of the brain on gene expression and the level of protein (superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase) activity were altered [40]. The shape of astrocytes was disturbed, cerebral capillaries were deformed, and edema was developed in adjacent areas [10][13][41]. In addition, the permeability of the blood–brain barrier increased in direct proportion to the dose of AgNPs received by animals [10].

After seven daily injections, impairments of working memory were noted in rats: The animals meaningfully more often made mistakes by repeatedly looking into the arm of the maze they had just examined; however, referential memory and the long-term understanding of the structure of space were not disturbed [41]. After three weeks of injections, the social behavior of the mice differed significantly from the normal behavior in the study by Greish et al. [42] The mice administrated with AgNPs preferred to stay in an empty chamber rather than to familiarize themselves with new animals. In experimental animals, motor coordination and balance were impaired, but the swimming speed in the Morris test was preserved, which revealed the absence of spatial memory formation in individuals treated with AgNPs. The emotional state, the level of anxiety, and the ability to conditioned-reflex learning, in which fear is the motivation, were considered in the study by Antsiferova et al. [43]. After long-term (1–6 months) oral contact with small doses of AgNPs (50 µg) through drinking water, the authors recorded and interpreted the test results as two attempts of the brain to adapt to the effects of AgNPs. Thus, after 2 months of contact, anxiety and fear increased, and after 4 months, they decreased with a simultaneous increase in exploratory behavior. After continued contact with AgNPs (up to 6 months), the impairment of long-term memory and conditioned-reflex learning was observed. The fading effect was noted in the research by González et al. [34]. Although several days after exposure to AgNPs, zebrafish larvae were hyperactive at changes in illumination, no fluctuations in their activity were detected after 5 days.

The influence of prenatal contact with AgNPs on the brain and behavior is described in a limited number of studies. After regular injections of AgNPs to future mothers during pregnancy, the spatial memory of their offspring was impaired, while conditioned-reflex learning and the emotional state of young rats did not differ from the offspring of the control group [44]. The experimental offspring demonstrated signs of depressive-like behavior, i.e., passivity and lack of interest in food [45]. After zebrafish embryos were exposed to AgNP solution, their avoidance motor response to the touch was disrupted; the membrane potentials of their motoneurons were decreased, and the expression of many genes connected with neurogenesis was low [46].

In studies of the effect of AgNP coating material (BSA, polyethylene glycol, and citrate) on cognition, spatial memory, and neurotransmitter levels in the rat hippocampus, only rats administrated with citrate-coated NPs maintained long-term spatial memory. For other NPs and Ag+, the induction of peripheral inflammation, which was reflected by alterations in the level of serum inflammatory mediators, was observed [47]. Wu et al. [48] showed a significant reduction in GAP-43 mRNA and protein expression in the hippocampus of offspring exposed to uncoated AgNPs, suggesting cognitive impairments in rats.

However, in some studies on adult animals, after subchronic contact with AgNPs, no behavioral disturbances were noticed. In the study by Liu et al. [49], no significant differences between experimental and control mice in the formation of spatial and working memory were found, and secondary neurogenesis in the hippocampus was not impaired. In the research by Dabrowska-Bouta et al. [12], pathological changes in the structure of myelin sheaths and a decrease in the level of three myelin-specific proteins were detected in the brain of experimental rats treated with AgNPs or Ag+. However, neither motion nor exploratory behavior or memory was impaired in animals treated with silver nanoparticles present in the two forms. After an intranasal introduction of AgNPs, experimental mice coped with the recognition of a new object in the same way as the control ones; however, their spatial memory was presumably impaired, while the ability for spatial learning itself did not decrease [50]. After AgNPs were injected into lactating mice, their grown offspring, which contacted with AgNPs through milk, did not differ from control animals in terms of their emotional state, social interactions, and locomotion [51].

4. AgNPs Effect on the Brain and Behavior

To study the effect of AgNPs on the brain and behavior, experiments were performed on mice exposed to AgNPs in adulthood [52]. The animals received a solution of AgNPs (size 25 nm; polyvinylpyrrolidone as coating agent) at a concentration of 25 μg/mL for 2 or 4 months, while control individuals drank pure water. When consuming compound animal feedstuff, one mouse drank an average of 5.38 mL of liquid per day; consequently, the daily dose of AgNPs per mouse was 4.5 and 5 mg/kg of body weight for males and females, respectively. At the end of the experiment, the learning ability and spatial memory of the animals were assessed in the Morris water maze (MWM) [53]. In this standard behavioral test, an underwater platform on which the animal can climb to come out of the water is placed in a round white pool filled with water colored and turbid with milk powder. The task of the animal is to find this platform and memorize its location relative to the out-of-labyrinth landmarks [53] in order to use its spatial memory next time to find the platform quicker. The methodology for conducting tests is described in detail in [52].

To establish a correlation between possible cognitive impairments in the brain of animals exposed to NPs and the level of AgNPs accumulated in the brain, the silver content in the brain, as well as in other tissues and organs, was determined after the animals’ slaughter using NAA [54]. NAA, due to the possibility of determining a wide number of elements in biological samples, allows assessing the content of silver and iron in organs and blood samples, estimating the passage of nanoparticles through the blood–brain barrier, and quantifying its accumulation in the neuronal tissues of the brain. The technique is described in detail in [52][54].

According to the NAA results, the relative mass of silver in the brain of experimental animals was 319 ± 155 ng after 2 months of nanoparticle intake and 870 ± 200 ng after 4 months, which is significantly higher, almost an order of magnitude, than the silver content in the control group [52]. Notwithstanding the accumulation of silver in the brain, within groups of individuals with a preference for different behavioral strategies in the MWM (for details, see [55]), adult experimental animals learned to find the platform just as successfully as control ones. In experiments in which the period of AgNP intake passed after the initial testing, which made it possible to identify groups of individuals with a preference for different behavioral strategies in the test [52], all mice retained learned information about the test for 2 and 4 months. Thus, it was concluded that in adult animals, the long-term oral consumption of AgNPs did not impair the ability to form spatial memory, as well as the ability to store and apply information learned before exposure to AgNPs.

Following this series of experiments, a study was carried out that simulated the effect of AgNPs on children born by women employed in the production industry or who were in close contact with AgNPs during pregnancy and lactation at home [56]. During the entire period of pregnancy and lactation (2 months in total), female mice were given to drink a solution of AgNPs (size 25 nm; polyvinylpyrrolidone as coating agent) with a concentration of 25 μg/mL. Thus, their offspring were exposed to AgNPs during prenatal development and early postnatal development. When the pups reached the age of 2 months, their learning ability and spatial memory were assessed in the MWM, while the silver content in their brain and the mother’s brain was determined by NAA. It was found that within groups of individuals with a preference for different behavioral strategies in the MWM, experimental mice did not learn to find the platform, while control individuals coped with the task successfully. Silver accumulated in the brain of both mothers and pups was at a level comparable to that in adult mice after 2 months of silver NP intake (373 ± 75 ng and 385 ± 57 ng, respectively), which exceeded the silver content in the control group approximately 20 times [57]. This experiment clearly demonstrated that, firstly, AgNPs easily overcame various biological barriers (blood–brain, placental) and migrated from the mother’s body to the offspring’s body; secondly, the study revealed that the fragile body of a developing child, including its brain, in general, was more sensitive to the toxic effect of AgNPs than the body of an adult, even an elderly one.

References

- Burdușel, A.C.; Gherasim, O.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Mogoantă, L.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E. Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: An up-to-date overview. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 681.

- Temizel-Sekeryan, S.; Hicks, A.L. Global environmental impacts of silver nanoparticle production methods supported by life cycle assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104676.

- Bertrand, C.; Zalouk-Vergnoux, A.; Giambérini, L.; Poirier, L.; Devin, S.; Labille, J.; Perrein-Ettajani, H.; Pagnout, C.; Châtel, A.; Levard, C.; et al. The influence of salinity on the fate and behavior of silver standardized nanomaterial and toxicity effects in the estuarine bivalve Scrobicularia plana. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 2550–2561.

- Chien, H.W.; Kuo, C.J.; Kao, L.H.; Lin, G.Y.; Chen, P.Y. Polysaccharidic spent coffee grounds for silver nanoparticle immobilization as a green and highly efficient biocide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 168–176.

- Zhou, Y.; Hong, F.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, X.; Hong, J.; Ze, Y.; Wang, L. Nanoparticulate titanium dioxide-inhibited dendritic development is involved in apoptosis and autophagy of hippocampal neurons in offspring mice. Toxicol. Res. 2017, 6, 889–901.

- Bergamaschi, E.; Garzaro, G.; Jones, G.W.; Buglisi, M.; Caniglia, M.; Godono, A.; Bosio, D.; Fenoglio, I.; Canu, I.G. Occupational exposure to carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibres: More than a cobweb. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 745.

- McCormick, S.; Niang, M.; Dahm, M.M. Occupational Exposures to Engineered Nanomaterials: A Review of Workplace Exposure Assessment Methods. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2021, 8, 223–234.

- Meng, Q.; Meng, H.; Pan, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Qi, Y.; Huang, Y. Influence of nanoparticle size on blood-brain barrier penetration and the accumulation of anti-seizure medicines in the brain. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 271–281.

- Ceña, V.; Játiva, P. Nanoparticle crossing of blood-brain barrier: A road to new therapeutic approaches to central nervous system diseases. Nanomedicine 2018, 13, 1513–1516.

- Sharma, A.; Muresanu, D.F.; Lafuente, J.V.; Patnaik, R.; Tian, Z.R.; Buzoianu, A.D.; Sharma, H.S. Sleep Deprivation-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown and Brain Dysfunction are Exacerbated by Size-Related Exposure to Ag and Cu Nanoparticles. Neuroprotective Effects of a 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonist Ondansetron. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 52, 867–881.

- Flores-López, L.Z.; Espinoza-Gómez, H.; Somanathan, R. Silver nanoparticles: Electron transfer, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, beneficial and toxicological effects. Mini review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 16–26.

- Dąbrowska-Bouta, B.; Zięba, M.; Orzelska-Górka, J.; Skalska, J.; Sulkowski, G.; Frontczak-Baniewicz, M.; Talarek, S.; Listos, J.; Strużyńska, L. Influence of a low dose of silver nanoparticles on cerebral myelin and behavior of adult rats. Toxicology 2016, 363–364, 29–36.

- Moradi-Sardareh, H.; Basir, H.R.G.; Hassan, Z.M.; Davoudi, M.; Amidi, F.; Paknejad, M. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles on different tissues of Balb/C mice. Life Sci. 2018, 211, 81–90.

- Marinho, C.S.; Matias, M.V.F.; Toledo, E.K.M.; Smaniotto, S.; Ximenes-da-Silva, A.; Tonholo, J.; Santos, E.L.; Machado, S.S.; Zanta, C.L. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles on different tissues in adult Danio rerio. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 47, 239–249.

- Recordati, C.; De Maglie, M.; Bianchessi, S.; Argentiere, S.; Cella, C.; Mattiello, S.; Cubadda, F.; Aureli, F.; D’Amato, M.; Raggi, A.; et al. Tissue distribution and acute toxicity of silver after single intravenous administration in mice: Nano-specific and size-dependent effects. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2016, 13, 12.

- Rodriguez-Garraus, A.; Azqueta, A.; Vettorazzi, A.; de Cerain, A.L. Genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 251.

- Lebedová, J.; Hedberg, Y.S.; Odnevall Wallinder, I.; Karlsson, H.L. Size-dependent genotoxicity of silver, gold and platinum nanoparticles studied using the mini-gel comet assay and micronucleus scoring with flow cytometry. Mutagenesis 2018, 33, 77–85.

- Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Ingle, T.; Jones, M.Y.; Mei, N.; Boudreau, M.D.; Cunningham, C.K.; Abbas, M.; Paredes, A.M.; et al. Size- and coating-dependent cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles evaluated using in vitro standard assays. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 1373–1384.

- Gliga, A.R.; Skoglund, S.; Odnevall Wallinder, I.; Fadeel, B.; Karlsson, H.L. Size-dependent cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human lung cells: The role of cellular uptake, agglomeration and Ag release. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2014, 11, 11.

- Ivask, A.; Kurvet, I.; Kasemets, K.; Blinova, I.; Aruoja, V.; Suppi, S.; Vija, H.; Kakïnen, A.; Titma, T.; Heinlaan, M.; et al. Size-dependent toxicity of silver nanoparticles to bacteria, yeast, algae, crustaceans and mammalian cells in vitro. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102108.

- Butler, K.S.; Peeler, D.J.; Casey, B.J.; Dair, B.J.; Elespuru, R.K. Silver nanoparticles: Correlating nanoparticle size and cellular uptake with genotoxicity. Mutagenesis 2015, 30, 577–591.

- Lu, W.; Senapati, D.; Wang, S.; Tovmachenko, O.; Singh, A.K.; Yu, H.; Ray, P.C. Effect of surface coating on the toxicity of silver nanomaterials on human skin keratinocytes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 487, 92–96.

- El Badawy, A.M.; Silva, R.G.; Morris, B.; Scheckel, K.G.; Suidan, M.T.; Tolaymat, T.M. Surface charge-dependent toxicity of silver nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 283–287.

- Yang, X.; Gondikas, A.P.; Marinakos, S.M.; Auffan, M.; Liu, J.; Hsu-Kim, H.; Meyer, J.N. Mechanism of silver nanoparticle toxicity is dependent on dissolved silver and surface coating in caenorhabditis elegans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 1119–1127.

- Prokhorova, I.M.; Kibrik, B.S.; Pavlov, A.V.; Pesnya, D.S. Estimation of mutagenic effect and modifications of mitosis by silver nanoparticles. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2013, 156, 255–259.

- Lekamge, S.; Miranda, A.F.; Abraham, A.; Li, V.; Shukla, R.; Bansal, V.; Nugegoda, D. The toxicity of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) to three freshwater invertebrates with different life strategies: Hydra vulgaris, Daphnia carinata, and Paratya australiensis. Front. Environ. Sci. 2018, 6, 152.

- Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S. On the developmental toxicity of silver nanoparticles. Mater. Des. 2021, 203, 109611.

- Park, K.; Tuttle, G.; Sinche, F.; Harper, S.L. Stability of citrate-capped silver nanoparticles in exposure media and their effects on the development of embryonic zebrafish (Danio rerio). Arch. Pharm. Res. 2013, 36, 125–133.

- Massarsky, A.; Dupuis, L.; Taylor, J.; Eisa-Beygi, S.; Strek, L.; Trudeau, V.L.; Moon, T.W. Assessment of nanosilver toxicity during zebrafish (Danio rerio) development. Chemosphere 2013, 92, 59–66.

- Xin, Q.; Rotchell, J.M.; Cheng, J.; Yi, J.; Zhang, Q. Silver nanoparticles affect the neural development of zebrafish embryos. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 1481–1492.

- Pourali, P.; Nouri, M.; Ameri, F.; Heidari, T.; Kheirkhahan, N.; Arabzadeh, S.; Yahyaei, B. Histopathological study of the maternal exposure to the biologically produced silver nanoparticles on different organs of the offspring. Naunyn. Schmiedebergs. Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 393, 867–878.

- Lyu, Z.; Ghoshdastidar, S.; Rekha, K.R.; Suresh, D.; Mao, J.; Bivens, N.; Kannan, R.; Joshi, T.; Rosenfeld, C.S.; Upendran, A. Developmental exposure to silver nanoparticles leads to long term gut dysbiosis and neurobehavioral alterations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6558.

- Powers, C.M.; Slotkin, T.A.; Seidler, F.J.; Badireddy, A.R.; Padilla, S. Silver nanoparticles alter zebrafish development and larval behavior: Distinct roles for particle size, coating and composition. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2011, 33, 708–714.

- González, E.A.; Carty, D.R.; Tran, F.D.; Cole, A.M.; Lein, P.J. Developmental exposure to silver nanoparticles at environmentally relevant concentrations alters swimming behavior in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 3018–3024.

- Ema, M.; Okuda, H.; Gamo, M.; Honda, K. A review of reproductive and developmental toxicity of silver nanoparticles in laboratory animals. Reprod. Toxicol. 2017, 67, 149–164.

- Tang, J.; Xiong, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Wan, Z.; Xi, T. Influence of silver nanoparticles on neurons and blood-brain barrier via subcutaneous injection in rats. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 255, 502–504.

- Pulgar, V.M. Transcytosis to cross the blood brain barrier, new advancements and challenges. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1019.

- Saraiva, C.; Praça, C.; Ferreira, R.; Santos, T.; Ferreira, L.; Bernardino, L. Nanoparticle-mediated brain drug delivery: Overcoming blood-brain barrier to treat neurodegenerative diseases. J. Control. Release 2016, 235, 34–47.

- Pinheiro, R.G.R.; Coutinho, A.J.; Pinheiro, M.; Neves, A.R. Nanoparticles for targeted brain drug delivery: What do we know? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11654.

- Krawczyńska, A.; Dziendzikowska, K.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Lankoff, A.; Herman, A.P.; Oczkowski, M.; Królikowski, T.; Wilczak, J.; Wojewódzka, M.; Kruszewski, M. Silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles alter oxidative/inflammatory response and renin-angiotensin system in brain. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 85, 96–105.

- Hritcu, L.; Stefan, M.; Ursu, L.; Neagu, A.; Mihasan, M.; Tartau, L.; Melnig, V. Exposure to silver nanoparticles induces oxidative stress and memory deficits in laboratory rats. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2011, 6, 497–509.

- Greish, K.; Alqahtani, A.A.; Alotaibi, A.F.; Abdulla, A.M.; Bukelly, A.T.; Alsobyani, F.M.; Alharbi, G.H.; Alkiyumi, I.S.; Aldawish, M.M.; Alshahrani, T.F.; et al. The Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on Learning, Memory and Social Interaction in BALB/C Mice. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 148.

- Antsiferova, A.; Kopaeva, M.; Kashkarov, P. Effects of prolonged silver nanoparticle exposure on the contextual cognition and behavior of mammals. Materials 2018, 11, 558.

- Ghaderi, S.; Tabatabaei, S.R.F.; Varzi, H.N.; Rashno, M. Induced adverse effects of prenatal exposure to silver nanoparticles on neurobehavioral development of offspring of mice. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 40, 263–275.

- Tabatabaei, S.R.F.; Moshrefi, M.; Askaripour, M. Prenatal exposure to silver nanoparticles causes depression like responses in mice. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 77, 681–686.

- Zhao, G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Xu, L.; Xia, C.X.; Liu, J.X. Silver nanoparticles induce abnormal touch responses by damaging neural circuits in zebrafish embryos. Chemosphere 2019, 229, 169–180.

- Dziendzikowska, K.; Węsierska, M.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Wilczak, J.; Oczkowski, M.; Męczyńska-Wielgosz, S.; Kruszewski, M. Silver nanoparticles impair cognitive functions and modify the hippocampal level of neurotransmitters in a coating-dependent manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12706.

- Wu, J.; Yu, C.; Tan, Y.; Hou, Z.; Li, M.; Shao, F.; Lu, X. Effects of prenatal exposure to silver nanoparticles on spatial cognition and hippocampal neurodevelopment in rats. Environ. Res. 2015, 138, 67–73.

- Liu, P.; Huang, Z.; Gu, N. Exposure to silver nanoparticles does not affect cognitive outcome or hippocampal neurogenesis in adult mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 87, 124–130.

- Davenport, L.L.; Hsieh, H.; Eppert, B.L.; Carreira, V.S.; Krishan, M.; Ingle, T.; Howard, P.C.; Williams, M.T.; Vorhees, C.V.; Genter, M.B. Systemic and behavioral effects of intranasal administration of silver nanoparticles. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2015, 51, 68–76.

- Morishita, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takimura, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Namba, Y.; Nojiri, N.; Ishizaka, T.; Takao, K.; Yamashita, F.; Takuma, K.; et al. Distribution of Silver Nanoparticles to Breast Milk and Their Biological Effects on Breast-Fed Offspring Mice. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 8180–8191.

- Ivlieva, A.L.; Petritskaya, E.N.; Rogatkin, D.A.; Demin, V.A.; Glazkov, A.A.; Zinicovscaia, I.; Pavlov, S.S.; Frontasyeva, M.V. Impact of Chronic Oral Administration of Silver Nanoparticles on Cognitive Abilities of Mice. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 2021, 18, 250–265.

- Morris, R. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J. Neurosci. Methods 1984, 11, 47–60.

- Zinicovscaia, I.; Pavlov, S.S.; Frontasyeva, M.V.; Ivlieva, A.L.; Petritskaya, E.N.; Rogatkin, D.A.; Demin, V.A. Accumulation of silver nanoparticles in mice tissues studied by neutron activation analysis. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 318, 985–989.

- Ivlieva, A.L.; Petritskaya, E.N.; Rogatkin, D.A.; Demin, V.A. Methodological Characteristics of the Use of the Morris Water Maze for Assessment of Cognitive Functions in Animals. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2017, 47, 484–493.

- Ivlieva, A.L.; Petritskaya, E.N.; Lopatina, M.V.; Rogatkin, D.A.; Zinkovskaya, I. Evaluation of the cognitive abilities of mice exposed to silver nanoparticles during prenatal development and lactation. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Forum on Cognitive Modeling, Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–22 July 2019.

- Zinicovscaia, I.; Grozdov, D.; Yushin, N.; Ivlieva, A.; Petritskaya, E.; Rogatkin, D. Neutron activation analysis as a tool for tracing the accumulation of silver nanoparticles in tissues of female mice and their offspring. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2019, 322, 1079–1083.

More

Information

Subjects:

Developmental Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

737

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

26 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No