| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | John O. Warner | -- | 2252 | 2022-04-21 15:15:53 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 1 word(s) | 2253 | 2022-04-22 05:41:36 | | |

Video Upload Options

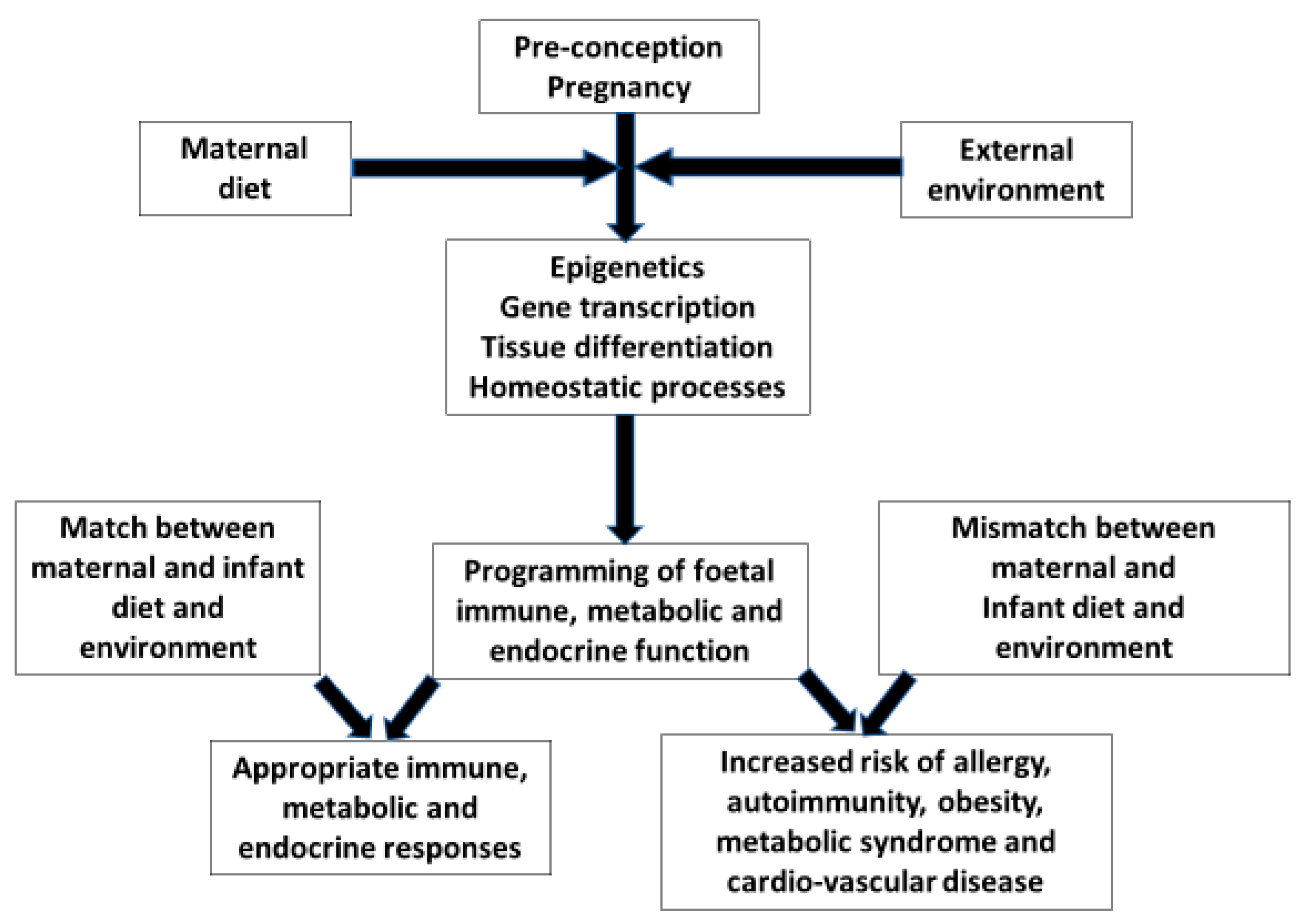

Complex interactions at the materno-placental-foetal interface have a profound influence on the infants’ immune maturation and the likelihood of developing allergic sensitisation and disease. Gene/environment interactions and timing of exposures through pregnancy add further degrees of complexity. Understanding the early life origins of allergy will only be possible by embracing this complexity. Studies will now need to investigate combinations of dietary, pollutant, medication and microbial exposures during pregnancy in relation to genomics, epigenomics, metagenomics and metabolomics and their effect on infant/child outcomes. Controlled trials of a “healthy diet” during pregnancy are likely to yield better outcomes than focusing on single nutrients which hitherto have produced disappointing results. The manipulation of the neonates’ evolving microbiome is suggested as another focus for controlled prevention trials.

1. Introduction

2. Foetal Nutrition and Allergic Disease

| Timing | Target | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-conception | Maternal obesity [13] | Weight loss No maternal or grand-mother smoking [32] |

| Pre-conception | Maternal nutrition | Healthy balanced diet [31] |

| Pregnancy | Maternal nutrition | More fish less meat Fresh fruit and vegetables [30] Optimal vitamins D, E and zinc [22][23][24][25] No allergen avoidance [33][34][35][36] |

| Pregnancy | Medications to avoid if possible | Antibiotics [17] Paracetamol [37] |

| Pregnancy | Maternal microbiome [38] | Pre-/pro-/syn-biotics [38] |

| Delivery | Avoid if possible | Caesarean section [14][15][16] Bottle feeding [39] |

| Neonatal period | Infant microbiome [38] | Breast feeding [39] Pre-/pro-/syn-biotics [38] |

References

- Susuki, K. The developing world of DOHaD. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2018, 9, 266–269.

- Crespi, B.J. Why and How Imprinted Genes Drive Fetal Programming. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 10, 940.

- Tham, E.H.; Loo, E.X.L.; Zhu, Y.; Shek, L.P.C. Effects of migration on allergic diseases. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 178, 128–140.

- Godfrey, K.; Barker, D.J.P.; Osmond, C. Disproportionate fetal growth and raised IgE concentration in adult life. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1994, 24, 641–648.

- Lucas, J.S.; Inskip, H.M.; Godfrey, K.M.; Foreman, C.T.; Warner, J.O.; Gregson, R.K.; Clough, J.B. Small size at birth and greater postnatal weight gain: Relationships to diminished infant lung function. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 170, 534–540.

- Tedner, S.G.; Örtqvist, A.K.; Almqvist, C. Fetal growth and risk of childhood asthma and allergic disease. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 1430–1447.

- Pike, K.C.; Crozier, S.R.; Lucas, J.S.; Inskip, H.M.; Robinson, S.; Roberts, G.; Godfrey, K.M. Southampton Women’s Survey Study Group. Patterns of fetal and infant growth are related to atopy and wheezing disorders at age 3 years. Thorax 2010, 65, 1099–1106.

- Erkkola, M.; Nwaru, B.I.; Kaila, M.; Kronberg-Kippilä, C.; Ilonen, J.; Simell, O.; Veijola, R.; Knip, M.; Virtanen, S. Risk of asthma and allergic outcomes in the offspring in relation to maternal food consumption during pregnancy: A Finnish birth cohort study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 23, 186–194.

- Calvani, M.; Alessandri, C.; Sopo, S.M.; Panetta, V.; Pingitore, G.; Tripodi, S.; Zappala, D.; Zicari, A.M.; the Lazio Association of Pediatric Allergology (APAL) Study Group. Consumption of fish, butter and margarine during pregnancy and development of allergic sensitizations in the offspring: Role of maternal atopy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2006, 17, 94–102.

- Bédard, A.; Northstone, K.; Henderson, A.J.; Shaheen, S.O. Maternal intake of sugar during pregnancy and childhood respiratory and atopic outcomes. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700073.

- Beckhaus, A.A.; Garcia-Marcos, L.; Forno, E.; Pacheco-Gonzalez, R.M.; Celedon, J.C.; Castro-Rodriguez, J.A. Maternal nutrition during pregnancy and risk of asthma, wheeze, and atopic diseases during childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2015, 70, 1588–1604.

- Bédard, A.; Li, Z.; Ait-hadad, W.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Leynaert, B.; Pison, C.; Dumas, O.; Varraso, R. The Role of Nutritional Factors in Asthma: Challenges and Opportunities for Epidemiological Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021, 18, 3013.

- Rizzo, G.S.; Sen, S. Maternal obesity and immune dysregulation in mother and infant: A review of the evidence. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2015, 16, 251–257.

- Darabi, B.; Rahmati, S.; Hafeziahmadi, M.R.; Badfar, G.; Azami, M. The association between caesarean section and childhood asthma: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 1–13.

- Mitselou, N.; Hallberg, J.; Stephansson, O.; Almqvist, C.; Melén, E.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Cesarean delivery, preterm birth, and risk of food allergy: Nationwide Swedish cohort study of more than 1 million children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 1510–1514.

- Chu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, B.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, J. Cesarean section without medical indication and risks of childhood allergic disorder, attenuated by breastfeeding. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9762.

- Metzler, S.; Frei, R.; Schmaußer-Hechfellner, E.; von Mutius, E.; Pekkanen, J.; Karvonen, A.M.; Kirjavainen, P.V.; Dalphin, J.C.; Divaret-Chauveau, A.; Riedler, J.; et al. Association between antibiotic treatment during pregnancy and infancy and the development of allergic diseases. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 30, 423–433.

- Miles, E.A.; Calder, P.C. Can Early Omega-3 Fatty Acid Exposure Reduce Risk of Childhood Allergic Disease? Nutrients 2017, 9, 784.

- Barman, M.; Stråvik, M.; Broberg, K.; Sandin, A.; Wold, A.E.; Sandberg, A.-S. Proportions of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Umbilical Cord Blood at Birth Are Related to Atopic Eczema Development in the First Year of Life. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3779.

- Larsen, V.G.; Ierodiakonou, D.; Jarrold, K.; Cunha, S.; Chivinge, J.; Robinson, Z.; Geoghegan, N.; Ruparelia, A.; Devani, P.; Trivella, M.; et al. Diet during pregnancy and infancy and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002507.

- Wu, S.; Li, C. Influence of Maternal Fish Oil Supplementation on the Risk of Asthma or Wheeze in Children: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 817110.

- Wöbke, T.K.; Sorg, B.L.; Steinhilber, D. Vitamin D in inflammatory diseases. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 244.

- Tareke, A.A.; Hadgu, A.A.; Ayana, A.M.; Zerfu, T.A. Prenatal vitamin D supplementation and child respiratory health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Allergy Organ. J. 2020, 13, 100486.

- Hypponen, E.; Berry, D.J.; Wjst, M.; Power, C. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and IgE-a significant but nonlinear relationship. Allergy 2009, 64, 613–620.

- Chen, L.W.; Lyons, B.; Navarro, P.; Shivappa, N.; Mehegan, J.; Murrin, C.M.; Hébert, J.R.; Kelleher, C.C.; Phillips, C.M. Maternal dietary inflammatory potential and quality are associated with offspring asthma risk over 10-year follow-up: The Lifeways Cross-Generation Cohort Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 111, 440–447.

- Wang, J.G.; Liu, B.; Kroll, F.; Hanson, C.; Vicencio, A.; Coca, S.; Uribarri, J.; Bose, S. Increased advanced glycation end product and meat consumption is associated with childhood wheeze: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Thorax 2021, 76, 292–294.

- Venter, C.; Pickett, K.; Starling, A.; Maslin, K.; Smith, P.K.; Palumbo, M.P.; O’Mahony, L.; Ben Abdallah, M.; Dabelea, D. Advanced glycation end product intake during pregnancy and offspring allergy outcomes: A Prospective cohort study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2021, 51, 1459–1470.

- Castro-Rodriguez, J.A.; Garcia-Marcos, L. What Are the Effects of a Mediterranean Diet on Allergies and Asthma in Children? Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 72.

- Bédard, A.; Northstone, K.; Henderson, A.J.; Shaheen, S.O. Mediterranean diet during pregnancy and childhood respiratory and atopic outcomes: Birth cohort study. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1901215.

- Amati, F.; Hassounah, S.; Swaka, A. The Impact of Mediterranean Dietary Patterns During Pregnancy on Maternal and Offspring Health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1098.

- Grimshaw, K.E.; Maskell, J.; Oliver, E.M.; Morris, R.C.; Foote, K.D.; Mills, E.C.; Margetts, B.M.; Roberts, G. Diet and food allergy development during infancy: Birth cohort study findings using prospective food diary data. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 511–519.

- Lodge, C.J.; Brabak, L.; Lowe, A.J.; Dharmage, S.C.; Olsson, D.; Forsberg, B. Grandmaternal smoking increases asthma risk in grandchildren: A nationwide Swedish cohort. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018, 48, 167–174.

- Richgels, P.K.; Yamani, A.; Chougnet, C.A.; Lewkowich, I.P. Maternal house dust mite exposure during pregnancy enhances severity of house dust mite–induced asthma in murine offspring. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 1404–1415.

- Torrent, M.; Sunyer, J.; Garcia, R.; Harris, J.; Iturriaga, M.V.; Puig, C.; Vall, O.; Antó, J.M.; Taylor, A.J.N.; Cullinan, P. Early-Life Allergen Exposure and Atopy, Asthma, and Wheeze up to 6 Years of Age. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 446–453.

- Liccardi, G.; Cazzola, M.; Canonica, G.W.; Passalacqua, G.; D’Amato, G. New insights in allergen avoidance measures for mite and pet sensitized patients. A critical appraisal. Respir. Med. 2005, 99, 1363–1376.

- Kramer, M.S.; Kakuma, R. Maternal dietary antigen avoidance during pregnancy or lactation, or both, for preventing or treating atopic disease in the child. Evid. Based Child Health A Cochrane Rev. J. 2014, 9, 447–483.

- Perzanowski, M.S.; Miller, R.L.; Tang, D.; Ali, D.; Garfinkel, R.S.; Chew, G.L.; Goldstein, I.F.; Perera, F.P.; Barr, R.G. Prenatal acetaminophen exposure and risk of wheeze at age 5 years in an urban low-income cohort. Thorax 2010, 65, 118–123.

- Peroni, D.G.; Nuzzi, G.; Trambusti, I.; Di Cicco, M.E.; Comberiati, P. Microbiome Composition and Its Impact on the Development of Allergic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 700.

- Zepeda-Ortega, B.; Goh, A.; Xepapadaki, P.; Sprikkelman, A.; Nicolaou, N.; Hernandez, R.E.H.; Latiff, A.H.A.; Yat, M.T.; Diab, M.; Hussaini, B.A.; et al. Strategies and Future Opportunities for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Cow Milk Allergy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 1877.