Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lin Jiang | -- | 2406 | 2022-04-21 10:10:12 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2406 | 2022-04-21 10:37:36 | | | | |

| 3 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2406 | 2022-04-21 10:38:59 | | | | |

| 4 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2406 | 2022-04-21 10:42:46 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Jiang, L.; Lai, Y.; Chen, K.; Tang, X. Drives of Urban Village Redevelopment. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22081 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Jiang L, Lai Y, Chen K, Tang X. Drives of Urban Village Redevelopment. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22081. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Jiang, Lin, Yani Lai, Ke Chen, Xiao Tang. "Drives of Urban Village Redevelopment" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22081 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Jiang, L., Lai, Y., Chen, K., & Tang, X. (2022, April 21). Drives of Urban Village Redevelopment. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22081

Jiang, Lin, et al. "Drives of Urban Village Redevelopment." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Urban village redevelopment generally refers to the demolition and rehabilitation of urban village buildings, involving several complicated processes, including urban space rebuilding, land ownership transformation, land value increment, and spatial benefit redistribution, which have attracted serious attention from the academic community in the past decades. At least three main processes from demand, supply and state interventions perspectives have driven urban village redevelopment in China.

urban village redevelopment

driving forces

informal space

1. Introduction

Given its rapid urbanization and the emergence of substantial demand for urban land, China is currently facing an unprecedented challenge of sustainable urban development and economic growth. Some large cities in China are at the bottleneck of urban development because the land resources for further development have become finite. Against this background, urban renewal has become a crucial component of urban development [1][2]. In Chinese cities, collective land exists in urban villages, which results from village-led land conversion and construction activities [3][4]. Dominated by villagers’ interests, village-led development of urban villages has led to multifarious negative outcomes, such as limited land property rights [5][6], inadequate infrastructure [7][8], potential safety hazards [9], and inefficient land use [6][10]. To the governments, the problems of urban villages require urgent solutions, and the governance of urban villages is the main issue in urban development [11][12][13]. Therefore, urban village rebuilding has become an important component in the practice of urban renewal in China to meet the emerging land-use needs, attract further investment, and sustain economic growth.

Urban village redevelopment generally refers to the demolition and rehabilitation of urban village buildings, involving several complicated processes, including urban space rebuilding [6], land ownership transformation [14], land value increment [15], and spatial benefit redistribution [16], which have attracted serious attention from the academic community in the past decades. A wealth of studies have investigated the role and relations of different stakeholders in the redevelopment processes based on empirical cases [16][17][18]. The main participants in the urban village redevelopment include the local governments, real estate developers, and local villagers [19]. Different types of governance modes have been adopted in the processes of urban village redevelopment, such as the government-led model [16][20][21], market-led model [22][23], and collective-led model [14][22][24], to name a few. Different governance models have led to dissimilar collaborative relationships among the relevant stakeholders [25]. Some studies focused on the socio-economic consequences of urban village redevelopment. Urban village redevelopment has been well recognized as having brought profound and diversified impacts to various social groups and urban spaces. On the one hand, the urban village redevelopment has improved land use efficiency [6][26] and has been found to have positive effects on the surrounding housing prices [27]. On the other hand, urban village redevelopments have resulted in a large-scale displacement of migrants [21][28][29] and have brought negative impacts to these people who have made fundamental contributions to urban development [30][31][32]. Another pool of literature has made efforts to propose strategies for better redevelopment of urban villages in the future. More inclusive governance and planning strategies are necessary for sustainable redevelopment [26][33]. To realize the diverse objectives of urban development, a better understanding on the driving processes of urban village redevelopment is a prerequisite. However, a lack of comprehensive understanding persists on the drivers of urban village redevelopment in China.

2. Drivers of Urban Village Redevelopment in China

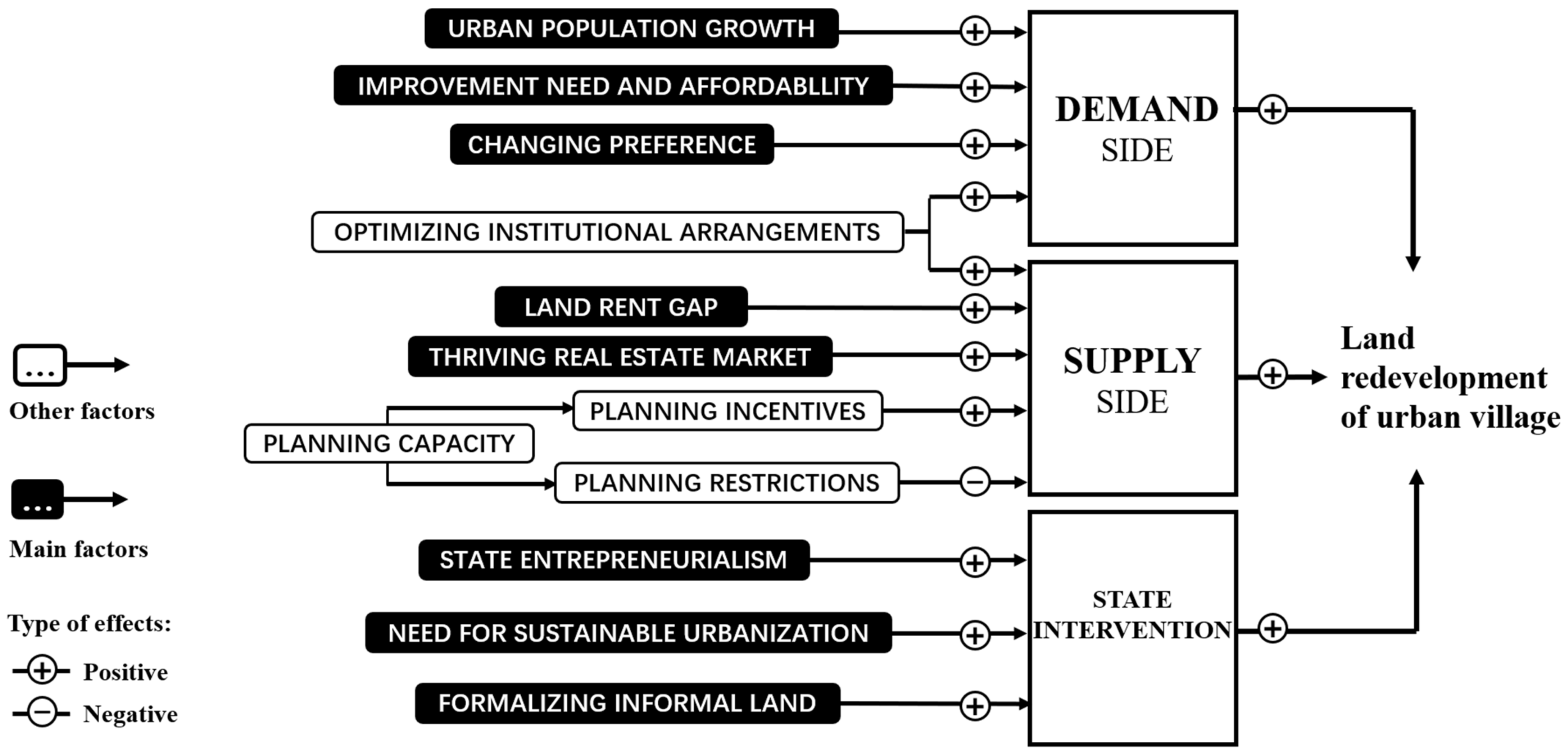

Based on a critical content analysis of the surveyed literature, researchers found at least three main processes which have driven urban village redevelopment in China. First, the growth of urban population and income level in the ongoing urbanization process has created an emerging solid demand to improve urban living conditions, which have triggered the restructuring of urban villages with sub-standard built environment into high-quality urban spaces. Second, from the production side, the market-oriented land reforms and the developers’ pursuit of land-related investment returns from the land rent gap is also a strong driving force for the demolition and rebuilding of urban villages. Lastly, the states and the regional governments have played a prominent part in promoting urban village redevelopment and integrating informal urban spaces into formal urban areas (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simplified scheme of the main drivers identified in the literature.

Figure 1. Simplified scheme of the main drivers identified in the literature.2.1. Emerging Demand for Improvement of Urban Living Conditions

The considerable rise in the urban population and income level in the ongoing urbanization process has created a strong market demand for high-quality living spaces in cities, especially in large cities [34][35][36]. In the 1980s, at the beginning of reform and development, China’s urban population and income were both in their infancy. At that time, the urban population was 191 million. With the rapid development of China’s cities and the growth of the urban economy, the urban population has increased significantly. According to the seventh national census, the national population reached 1,411,778,724 by 2020, among which the urban population was over 900 million. A large number of migrants have chosen to live in megacities for job opportunities, such as Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Nanjing [37][38][39]. In the case of Shenzhen, which is located in the Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration, it was originally a small fishing village before reform and opening up. In less than forty years, Shenzhen has become one of China’s most populous and prosperous megacities. Shenzhen’s urban population has reached more than 17 million by 2020, and most migrants still live in urban villages [3]. The rapid growth of urban population and the aggregation of well-educated people provided sufficient impetus for urban economic development, which generally increased residents’ average income and consumption level [40]. The increase in urban population and disposable income has created a strong demand for high-quality housing conditions in recent years. Recent research shows that urban residents increasingly prefer new housing with a larger area, better building quality, improved environment [41][42], and sufficient facilities such as advanced medical care and high-quality education resources [43]. According to the UN, China’s urbanization rate will continue to increase in the coming years and reach 70% by 2030. The need to improve urban living conditions in megacities will become even more pressing [44]. Such needs can no longer be fulfilled by the informal housing provided by urban villages [21].

However, high-quality formal housing remains extremely limited in Chinese megacities. For example, in 2007, Shenzhen boasted merely one million commercial, residential units. The number increased to 1.89 million in 2020, which can only accommodate a small portion of the urban residents living in this city. Although the municipal government has made efforts to provide public housing in recent years, the stock of developed public housing is very limited. One of the specific consequences of the urbanization and land reform processes that transpired in the 1980s is that a high percentage of land within the boundaries of megacities is occupied by urban villages [8][45]. The inner conditions of urban villages are often crowded and disordered [7]. Urban villages always have high-density and poor-quality buildings [46]. The surrounding environment of urban villages typically lacks high-quality infrastructure and public service [47], among others. In the earlier urban development stage, the presence of urban villages was critical because they served as sites of affordable housing and living space for the influx of urban migrants [48][49]. In terms of the demand side, the main driver of gentrification in the West is the desire to return to the city centre [50]. By contrast, the emerging needs of China’s urban dwellers are largely reflected in the urgent demand for better living conditions. With the rising income levels, urban residents have changed their preferences of living conditions and can afford better living. Most urban villages with sub-standard environments have failed to meet the new needs for improving living conditions [41]. The mismatch between the emerging demand and the unsatisfactory urban living conditions in urban villages becomes an essential problem in megacities. In such context, the redevelopment of urban villages into high-quality formal housing estates has become an important means to fulfil the emerging housing demands [24][51].

2.2. Capital Accumulation and Developers’ Pursuit of Land-Related Investment Returns

From the supply side, profit-oriented urban capital accumulation via land-related investment has become a key driver of spatial reproduction in the global urban depressed areas [52][53]. According to Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith [54], urban space is an important carrier to absorb capital appreciation. The reconfiguration of urban space has been heavily influenced by the rationale of capital accumulation which is now a symbolic representation of real estate values [55]. Accordingly, the land redevelopment process in urban renewal can be understood as a continuous spatial reproduction of urban depressed space [52], which is an important way to realize capital accumulation. A wealth of studies have investigated the vital role of capital accumulation in shaping the redevelopment process and outcomes in different local contexts [56][57]. According to Marxist geographer Neil Smith [58], the land rent gap is a fundamental concept to understanding land redevelopment from the perspective of capital accumulation. Specifically, the land rent gap denotes the difference between the financial returns generated by a property due to current land use and the probable returns caused if the property were put to more lucrative use. When this rent gap becomes sufficiently large for developers to reap significant investment returns from this process, redevelopment will occur. From this perspective, urban capital and developers in different countries have similar aims in relation to urban redevelopment activities, not least in respect of land-related investment returns. However, their roles and influence in this sphere may vary in accordance with difference in local renewal contexts [56][57].

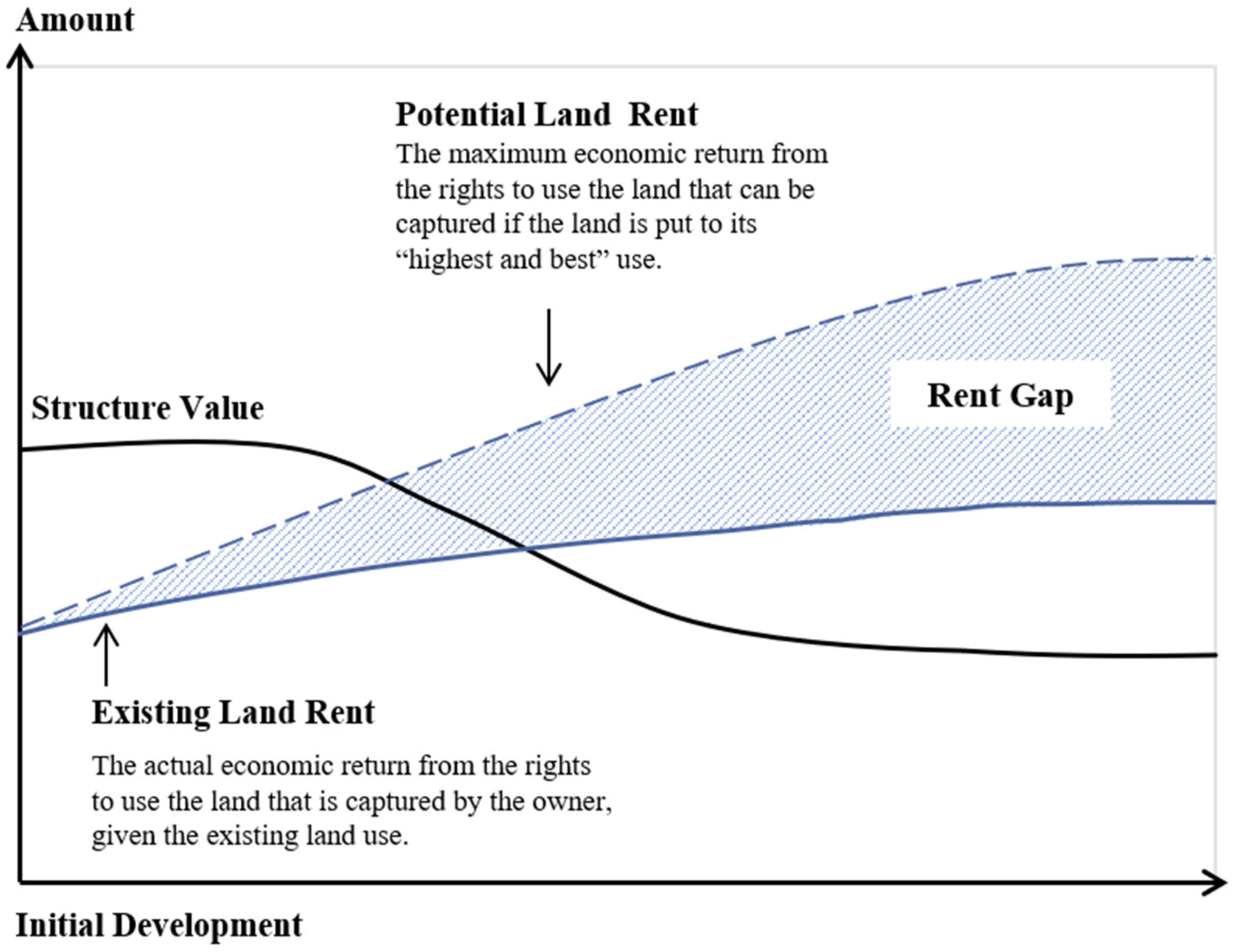

With the reform of urban land system marked by the separation of the land use rights and state land ownership, a prosperous land market has been formed in China [59]. Capital accumulation and developers’ pursuit of land-related investment returns from the rent gap becomes a powerful force for urban village redevelopment in China [10][60][61]. The public infrastructure and planning policies during dynamic urbanization have substantially impacted the land rent gap. When the surrounding urban environment and infrastructure are improved, the potential rent of the urban village area keeps rising rapidly. By contrast, due to the suboptimal land use and disorganized physical environment [62], the existing land rent in urban villages has been low for a long time. The formation of land rent gap makes it profitable for developers to redevelop urban villages for “highest and best” use (Figure 2). According to previous literature, well-located urban villages, such as in large cities or close to urban centres, are supposed to experience earlier redevelopment in comparison to villages located in outlying zones [21][63]. However, a recent study shows that the land rent gap of urban villages is also affected by many other factors like land ownership and rights, existing land use, and planned land use. These factors collectively affected the land rent gap as well as the attributes of transaction costs in the redevelopment processes and shaped redevelopment outcomes [64]. On the one hand, capital accumulation and developers’ pursuit of land-related investment returns has promoted the demolition and rebuilding of urban villages and has contributed to many formal housing units via redevelopment [65]. On the other hand, market-oriented redevelopment of urban villages has brought some negative impacts to some vulnerable social groups and the city. Migrants have been forced to move out of urban villages. This phenomenon will inevitably threaten social sustainability in urban development [27][66].

Figure 2. Development of rent gap in urban villages.

Figure 2. Development of rent gap in urban villages.2.3. Important Role of the States and Local Governments

The local states have played a critical role in the land redevelopment processes [18][67]68]. Along with the constant market-oriented reforms over the past years, the state increasingly relies on market approaches to stimulate redevelopment activities and realize developmental objectives known as “state entrepreneurialism” [69,70,71]. With limited resources, fierce competition exists among local governments for urban growth and development [59,68]. Under such a background, the local states have strong motivations to attract investments and migrants for urban development [72]. However, the widely existing informal urban lands, such as urban villages, have become a huge obstacle to sustainable development [73,74]. A large-scale informal urban space based on collective land lacks legal property rights and is outside the urban planning and land management system [75], which fails to support high-quality urban development [76]. In the case of Shenzhen, where land resources are extremely scarce, urban villages (393.3 km2) accounted for more than 55% of the entire urban area (703.5 km2) at the end of 2006 [3]. Such informal space developed by the villages has led to a disordered built environment with inadequate public infrastructure and service provision. In this research, demolition and rebuilding of urban villages have been imperative for achieving the objective of sustainable urban development. To the local governments, urban village redevelopment has a strong potential to achieve multiple development goals. In contrast to the passive intervention responses to the dominant market mechanisms, such as fixing externalities of urban redevelopment [77,78], Chinese national and local states are more proactive in shaping the processes and outcomes of urban redevelopment.

The role of the local governments has experienced a marked change in triggering and enabling the urban village redevelopment during the past decades [67][68]. Traditionally, the local governments dominated the process of urban renewal. They have rights to select redevelopment sites, make a top-down land use planning system for redevelopment [67][69], choose developers for redevelopment, and resettle affected villagers in the redevelopment process [21]. Such a state-led redevelopment process of urban villages has negative externalities. For example, the high cost and inefficiency of redevelopment fail to meet the requirements of high-speed urban development [70]. Meanwhile, such forced demolition and reconstruction also somewhat neglected the rights and interests of diverse stakeholders [14], leading to a large number of displacements of local villagers [31][71]. Along with the market-oriented reforms on land (re)development, the role of the local governments has profoundly transformed in the redevelopment of urban villages. They have strong incentives to promote the urban village redevelopment to integrate the informal settlements into formal and governable urban spaces. In many cities, the traditional state-led model of land redevelopment is supplemented with bottom-up market instruments [68][72]. In Guangdong Province, the land transfer is no longer required to get through a state requisition process. To improve the efficiency and reduce the cost of the redevelopment process, the local states increasingly rely on market actors to achieve redevelopment goals. In this case, market entities such as developers, property owners, and investment capital have become the most important actors to initiate and implement redevelopment projects in recent years [22][24][73][74]. The local states have paid increasing attention to regulatory guidance in redevelopment [66][75]. For example, they make regulations on the requirements of surveying the willingness of property owners and the qualifications of developers. Urban planning standards are carried out to guide the private planning for individual redevelopment projects [64]. The changing rules and policies have effectively promoted the redevelopment of urban villages in recent years, especially in Guangdong Province [3][14]. Nonetheless, the local states play critical roles in stimulating and regulating the redevelopment in the dynamic socio-economic environment.

References

- Liu, Y. Introduction to land use and rural sustainability in China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 1–4.

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Li, Y. Key issues of land use in China and implications for policy making. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 6–12.

- Lai, Y.N.; Chan, E.H.W.; Choy, L. Village-led land development under state-led institutional arrangements in urbanising China: The case of Shenzhen. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1736–1759.

- Hao, P.; Sliuzas, R.; Geertman, S. The development and redevelopment of urban villages in Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 214–224.

- Choy, L.H.T.; Lai, Y.; Lok, W. Economic performance of industrial development on collective land in the urbanization process in China: Empirical evidence from Shenzhen. Habitat Int. 2013, 40, 184–193.

- Tian, L. The Chengzhongcun land market in China: Boon or bane—A perspective on property rights. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2008, 32, 282–304.

- Hao, P.; Hooimeijer, P.; Sliuzas, R.; Geertman, S. What Drives the Spatial Development of Urban Villages in China? Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 3394–3411.

- Liu, Y.; He, S.; Wu, F.; Webster, C. Urban villages under China’s rapid urbanization: Unregulated assets and transitional neighbourhoods. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 135–144.

- Wang, Y.P.; Wang, Y.L.; Wu, J.S. Urbanization and Informal Development in China: Urban Villages in Shenzhen. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 957–973.

- Liu, S.Y.; Zhang, Y. Cities without slums? China’s land regime and dual-track urbanization. Cities 2020, 101, 102652.

- Wu, Y.Z.; Sun, X.F.; Sun, L.S.; Choguill, C.L. Optimizing the governance model of urban villages based on integration of inclusiveness and urban service boundary (USB): A Chinese case study. Cities 2020, 96, 102427.

- Zhang, L.; Ye, Y.M.; Chen, J. Urbanization, informality and housing inequality in indigenous villages: A case study of Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 32–42.

- Hussain, T.; Abbas, J.; Wei, Z.; Ahmad, S.; Bi, X.; Zhu, G. Impact of Urban Village Disamenity on Neighboring Residential Properties: Empirical Evidence from Nanjing through Hedonic Pricing Model Appraisal. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 04020055.

- Shi, C.; Tang, B.S. Institutional change and diversity in the transfer of land development rights in China: The case of Chengdu. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 473–489.

- Wu, W.J.; Wang, J.H. Gentrification effects of China’s urban village renewals. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 214–229.

- Zhou, Z.H. Towards collaborative approach? Investigating the regeneration of urban village in Guangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 297–305.

- Liu, G.; Wei, L.; Gu, J.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y. Benefit distribution in urban renewal from the perspectives of efficiency and fairness: A game theoretical model and the government’s role in China. Cities 2020, 96, 102422.

- Guo, Y.L.; Zhang, C.G.; Wang, Y.P.; Li, X. (De-)Activating the growth machine for redevelopment: The case of Liede urban village in Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1420–1438.

- Jiang, Y.P.; Mohabir, N.; Ma, R.F.; Wu, L.C.; Chen, M.X. Whose village? Stakeholder interests in the urban renewal of Hubei old village in Shenzhen. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104411.

- Li, L.H.; Lin, J.; Li, X.; Wu, F. Redevelopment of urban village in China—A step towards an effective urban policy? A case study of Liede village in Guangzhou. Habitat Int. 2014, 43, 299–308.

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.C. Urban village redevelopment in Beijing: The state-dominated formalization of informal housing. Cities 2018, 72, 160–172.

- Yuan, D.; Yau, Y.; Bao, H.; Lin, W. A Framework for Understanding the Institutional Arrangements of Urban Village Redevelopment Projects in China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104998.

- Liu, X.; Huang, J.; Zhu, J. Property-rights regime in transition: Understanding the urban regeneration process in China—A case study of Jinhuajie, Guangzhou. Cities 2019, 90, 181–190.

- Yang, Q.; Song, Y.; Cai, Y. Blending Bottom-Up and Top-Down Urban Village Redevelopment Modes: Comparing Multidimensional Welfare Changes of Resettled Households in Wuhan, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7447.

- Zhou, Y.; Lan, F.; Zhou, T. An experience-based mining approach to supporting urban renewal mode decisions under a multi-stakeholder environment in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105428.

- Lin, Y.L.; De Meulder, B. A conceptual framework for the strategic urban project approach for the sustainable redevelopment of "villages in the city" in Guangzhou. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 380–387.

- Liu, Y.; Tang, S.S.; Geertman, S.; Lin, Y.L.; Van Oort, F. The chain effects of property-led redevelopment in Shenzhen: Price-shadowing and indirect displacement. Cities 2017, 67, 31–42.

- He, S.J.; Liu, Y.T.; Wu, F.L.; Webster, C. Social Groups and Housing Differentiation in China’s Urban Villages: An Institutional Interpretation. Hous. Stud. 2010, 25, 671–691.

- Lin, Y.L.; De Meulder, B.; Cai, X.X.; Hu, H.D.; Lai, Y.N. Linking social housing provision for rural migrants with the redevelopment of ’villages in the city’: A case study of Beijing. Cities 2014, 40, 111–119.

- Li, M.; Xiong, Y.H. Demolition of Chengzhongcun and social mobility of Migrant youth: A case study in Beijing. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2018, 59, 204–223.

- Wong, S.W.; Tang, B.S.; Liu, J.L. Village Redevelopment and Desegregation as a Strategy for Metropolitan Development: Some Lessons from Guangzhou City. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 1064–1079.

- Zeng, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J. Urban village demolition, migrant workers’ rental costs and housing choices: Evidence from Hangzhou, China. Cities 2019, 94, 70–79.

- Li, X.; Hui, E.C.M.; Chen, T.T.; Lang, W.; Guo, Y.L. From Habitat III to the new urbanization agenda in China: Seeing through the practices of the "three old renewals" in Guangzhou. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 513–522.

- Haase, D.; Kabisch, N.; Haase, A. Endless Urban Growth? On the Mismatch of Population, Household and Urban Land Area Growth and Its Effects on the Urban Debate. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66531.

- Luo, J.J.; Zhang, X.L.; Wu, Y.Z.; Shen, J.H.; Shen, L.Y.; Xing, X.S. Urban land expansion and the floating population in China: For production or for living? Cities 2018, 74, 219–228.

- Moos, M. From gentrification to youthification? The increasing importance of young age in delineating high-density living. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 2903–2920.

- Cui, C.; Hooimeijer, P.; Geertman, S.; Pu, Y.X. Residential Distribution of the Emergent Class of Skilled Migrants in Nanjing. Hous. Stud. 2015, 30, 1235–1256.

- Mohabir, N.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, R. Chinese floating migrants: Rural-urban migrant labourers’ intentions to stay or return. Habitat Int. 2017, 60, 101–110.

- Yang, G.; Zhou, C.S.; Jin, W.F. Integration of migrant workers: Differentiation among three rural migrant enclaves in Shenzhen. Cities 2020, 96, 102453.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y. Upward or downward comparison? Migrants’ socioeconomic status and subjective wellbeing in Chinese cities. Urban Stud. 2020, 58, 2490–2513.

- Jing, H.; Zhimin, I.; Yang, S. Architectural Space Allocation in The Renovation of Urban Villages: Users Demand. Open House Int. 2019, 44, 118–129.

- Hu, W.; Li, L.; Su, M. Spatial Inequity of Multi-Level Healthcare Services in a Rapid Expanding Immigrant City of China: A Case Study of Shenzhen. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3441.

- Jiang, Y.P.; Waley, P.; Gonzalez, S. Nice apartments, no jobs: How former villagers experienced displacement and resettlement in the western suburbs of Shanghai. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 3202–3217.

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Hudson, J. Housing conditions and life satisfaction in urban China. Cities 2018, 81, 35–44.

- Zhan, Y. The urbanisation of rural migrants and the making of urban villages in contemporary China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1525–1540.

- Zhu, J.M. Path-dependent institutional change to collective land rights: The collective entrenched in urbanizing Guangzhou. J. Urban Aff. 2018, 40, 923–936.

- Huang, D.Q.; Huang, Y.C.; Zhao, X.S.; Liu, Z. How Do Differences in Land Ownership Types in China Affect Land Development? A Case from Beijing. Sustainability 2017, 9, 123.

- Hao, P.; Geertman, S.; Hooimeijer, P.; Sliuzas, R. Spatial Analyses of the Urban Village Development Process in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 2177–2197.

- Lin, Y.L.; De Meulder, B.; Wang, S.F. The interplay of state, market and society in the socio-spatial transformation of "villages in the city" in Guangzhou. Environ. Urban. 2012, 24, 325–343.

- Uitermark, J.; Duyvendak, J.W.; Kleinhans, R. Gentrification as a governmental strategy: Social control and social cohesion in Hoogvliet, Rotterdam. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 125–141.

- Liu, S.Q.; Yu, Q.; Wei, C. Spatial-Temporal Dynamic Analysis of Land Use and Landscape Pattern in Guangzhou, China: Exploring the Driving Forces from an Urban Sustainability Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6675.

- Raco, M. Remaking place and securitising space: Urban regeneration and the strategies, tactics and practices of policing in the UK. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1869–1887.

- Harvey, D. Between space and time—Reflections on the geographical imagination. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1990, 80, 418–434.

- Lefebvre, H.; Nicholson-Smith, D. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991; Volume 142.

- Delgado Ramos, G.C. Real Estate Industry as an Urban Growth Machine: A Review of the Political Economy and Political Ecology of Urban Space Production in Mexico City. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1980.

- Lopez-Morales, E.; Sanhueza, C.; Espinoza, S.; Ordenes, F.; Orozco, H. Rent gap formation due to public infrastructure and planning policies: An analysis of Greater Santiago, Chile, 2008–2011. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2019, 51, 1536–1557.

- Harrison, J. Rethinking City-regionalism as the Production of New Non-State Spatial Strategies: The Case of Peel Holdings Atlantic Gateway Strategy. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2315–2335.

- Smith, N. Gentrification and the Rent Gap. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1987, 77, 462–465.

- He, S.J.; Wu, F.L. Property-led redevelopment in post-reform China: A case study of Xintiandi redevelopment project in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2005, 27, 1–23.

- Hu, F.Z.Y. Industrial capitalisation and spatial transformation in Chinese cities: Strategic repositioning, state-owned enterprise capitalisation, and the reproduction of urban space in Beijing. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2799–2821.

- Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Gu, J. Urban renewal simulation with spatial, economic and policy dynamics: The rent-gap theory-based model and the case study of Chongqing. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 238–252.

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.C.; Liu, S.H. Peasants’ counterplots against the state monopoly of the rural urbanization process: Urban villages and ’small property housing’ in Beijing, China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2012, 44, 1219–1240.

- Wu, F.L.; Zhang, F.Z.; Webster, C. Informality and the Development and Demolition of Urban Villages in the Chinese Peri-urban Area. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1919–1934.

- Lai, Y.N.; Tang, B.S.; Chen, X.S.; Zheng, X. Spatial determinants of land redevelopment in the urban renewal processes in Shenzhen, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105330.

- Zhang, X.; Hu, J.; Skitmore, M.; Leung, B.Y.P. Inner-City Urban Redevelopment in China Metropolises and the Emergence of Gentrification: Case of Yuexiu, Guangzhou. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2014, 140, 05014004.

- Wu, F.; Li, L.H.; Han, S.Y. Social Sustainability and Redevelopment of Urban Villages in China: A Case Study of Guangzhou. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2116.

- Zhang, S.H.; De Roo, G.; Rauws, W. Understanding self-organization and formal institutions in peri-urban transformations: A case study from Beijing. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 287–303.

- He, S.J.; Wu, F.L. China’s Emerging Neoliberal Urbanism: Perspectives from Urban Redevelopment. Antipode 2009, 41, 282–304.

- Wu, F.L. Planning centrality, market instruments: Governing Chinese urban transformation under state entrepreneurialism. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1383–1399.

- Wu, F.L. The state acts through the market: ‘State entrepreneurialism’ beyond varieties of urban entrepreneurialism. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2020, 10, 326–329.

- Wu, F.L.; Phelps, N.A. (Post)suburban development and state entrepreneurialism in Beijing’s outer suburbs. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2011, 43, 410–430.

- Yuan, D.; Bao, H.; Yau, Y.; Skitmore, M. Case-Based Analysis of Drivers and Challenges for Implementing Government-Led Urban Village Redevelopment Projects in China: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 05020014.

- Song, Y.; Zenou, Y.; Ding, C. Let’s not throw the baby out with the bath water: The role of urban villages in housing rural migrants in China. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 313–330.

- Zheng, H.W.; Shen, G.Q.; Wang, H. A review of recent studies on sustainable urban renewal. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 272–279.

- Lai, Y.N.; Peng, Y.; Li, B.; Lin, Y.L. Industrial land development in urban villages in China: A property rights perspective. Habitat Int. 2014, 41, 185–194.

- Cai, M.N.; Sun, X. Institutional bindingness, power structure, and land expropriation in China. World Dev. 2018, 109, 172–186.

- Mcguirk, P.M.; Maclaran, A. Changing approaches to urban planning in an ‘entrepreneurial city’: The case of Dublin. European Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 437–457.

- Hackworth, J.; Smith, N. The changing state of gentrification. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2001, 92, 464–477.

- Lai, Y.N.; Tang, B.S. Institutional barriers to redevelopment of urban villages in China: A transaction cost perspective. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 482–490.

- Yuan, D.H.; Yau, Y.; Bao, H.J.; Liu, Y.S.; Liu, T. Anatomizing the Institutional Arrangements of Urban Village Redevelopment: Case Studies in Guangzhou, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3376.

- Shih, M. Rethinking displacement in peri-urban transformation in China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2017, 49, 389–406.

- Chen, Y.; Qu, L. Emerging Participative Approaches for Urban Regeneration in Chinese Megacities. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04019029.

- Wong, S.W.; Chen, X.; Tang, B.-S.; Liu, J. Neoliberal State Intervention and the Power of Community in Urban Regeneration: An Empirical Study of Three Village Redevelopment Projects in Guangzhou, China. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2021, 457–473.

- Tong, D.; Wu, Y.; Maclachlan, I.; Zhu, J. The role of social capital in the collective-led development of urbanising villages in China: The case of Shenzhen. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 3335–3353.

- Zhang, L.; Lin, Y.; Hooimeijer, P.; Geertman, S. Heterogeneity of public participation in urban redevelopment in Chinese cities: Beijing versus Guangzhou. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 1903–1919.

More

Information

Subjects:

Urban Studies

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.9K

Revisions:

4 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No