You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 1 by Lin Jiang.

Urban village redevelopment generally refers to the demolition and rehabilitation of urban village buildings, involving several complicated processes, including urban space rebuilding, land ownership transformation, land value increment, and spatial benefit redistribution, which have attracted serious attention from the academic community in the past decades. At least three main processes from demand, supply and state interventions perspectives have driven urban village redevelopment in China.

- urban village redevelopment

- driving forces

- informal space

1. Introduction

Given its rapid urbanization and the emergence of substantial demand for urban land, China is currently facing an unprecedented challenge of sustainable urban development and economic growth. Some large cities in China are at the bottleneck of urban development because the land resources for further development have become finite. Against this background, urban renewal has become a crucial component of urban development [1,2][1][2]. In Chinese cities, collective land exists in urban villages, which results from village-led land conversion and construction activities [3,4][3][4]. Dominated by villagers’ interests, village-led development of urban villages has led to multifarious negative outcomes, such as limited land property rights [5[5][6],6], inadequate infrastructure [7,8][7][8], potential safety hazards [9], and inefficient land use [6,10][6][10]. To the governments, the problems of urban villages require urgent solutions, and the governance of urban villages is the main issue in urban development [11,12,13][11][12][13]. Therefore, urban village rebuilding has become an important component in the practice of urban renewal in China to meet the emerging land-use needs, attract further investment, and sustain economic growth.

Urban village redevelopment generally refers to the demolition and rehabilitation of urban village buildings, involving several complicated processes, including urban space rebuilding [6], land ownership transformation [14], land value increment [15], and spatial benefit redistribution [16], which have attracted serious attention from the academic community in the past decades. A wealth of studies have investigated the role and relations of different stakeholders in the redevelopment processes based on empirical cases [16,17,18][16][17][18]. The main participants in the urban village redevelopment include the local governments, real estate developers, and local villagers [19]. Different types of governance modes have been adopted in the processes of urban village redevelopment, such as the government-led model [16[16][20][21],20,21], market-led model [22[22][23],23], and collective-led model [14,22[14][22][24],24], to name a few. Different governance models have led to dissimilar collaborative relationships among the relevant stakeholders [25]. Some studies focused on the socio-economic consequences of urban village redevelopment. Urban village redevelopment has been well recognized as having brought profound and diversified impacts to various social groups and urban spaces. On the one hand, the urban village redevelopment has improved land use efficiency [6,26][6][26] and has been found to have positive effects on the surrounding housing prices [27]. On the other hand, urban village redevelopments have resulted in a large-scale displacement of migrants [21,28,29][21][28][29] and have brought negative impacts to these people who have made fundamental contributions to urban development [30,31,32][30][31][32]. Another pool of literature has made efforts to propose strategies for better redevelopment of urban villages in the future. More inclusive governance and planning strategies are necessary for sustainable redevelopment [26,33][26][33]. To realize the diverse objectives of urban development, a better understanding on the driving processes of urban village redevelopment is a prerequisite. However, a lack of comprehensive understanding persists on the drivers of urban village redevelopment in China.

2. Drivers of Urban Village Redevelopment in China

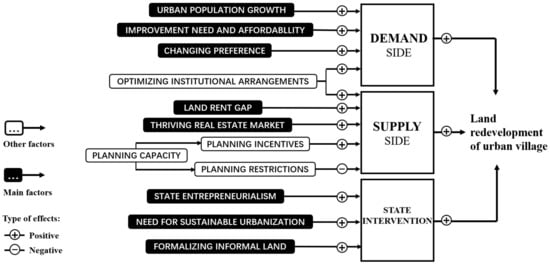

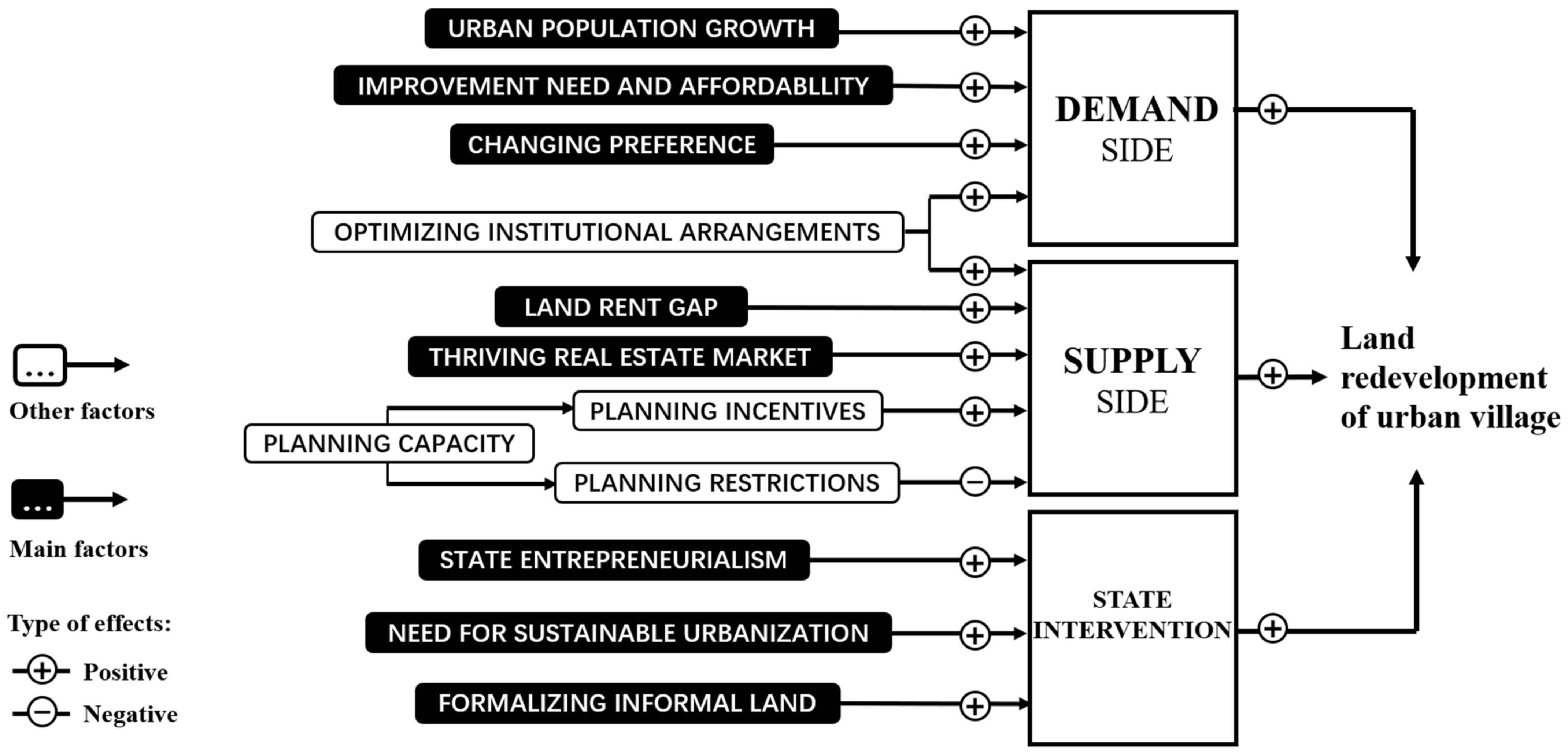

Based on a critical content analysis of the surveyed literature, wresearchers found at least three main processes which have driven urban village redevelopment in China. First, the growth of urban population and income level in the ongoing urbanization process has created an emerging solid demand to improve urban living conditions, which have triggered the restructuring of urban villages with sub-standard built environment into high-quality urban spaces. Second, from the production side, the market-oriented land reforms and the developers’ pursuit of land-related investment returns from the land rent gap is also a strong driving force for the demolition and rebuilding of urban villages. Lastly, the states and the regional governments have played a prominent part in promoting urban village redevelopment and integrating informal urban spaces into formal urban areas (Figure 41).

Figure 41. Simplified scheme of the main drivers identified in the literature.

Figure 41. Simplified scheme of the main drivers identified in the literature.2.1. Emerging Demand for Improvement of Urban Living Conditions

The considerable rise in the urban population and income level in the ongoing urbanization process has created a strong market demand for high-quality living spaces in cities, especially in large cities [34,35,36][34][35][36]. In the 1980s, at the beginning of reform and development, China’s urban population and income were both in their infancy. At that time, the urban population was 191 million. With the rapid development of China’s cities and the growth of the urban economy, the urban population has increased significantly. According to the seventh national census, the national population reached 1,411,778,724 by 2020, among which the urban population was over 900 million. A large number of migrants have chosen to live in megacities for job opportunities, such as Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Nanjing [37,38,39][37][38][39]. In the case of Shenzhen, which is located in the Pearl River Delta urban agglomeration, it was originally a small fishing village before reform and opening up. In less than forty years, Shenzhen has become one of China’s most populous and prosperous megacities. Shenzhen’s urban population has reached more than 17 million by 2020, and most migrants still live in urban villages [3]. The rapid growth of urban population and the aggregation of well-educated people provided sufficient impetus for urban economic development, which generally increased residents’ average income and consumption level [40]. The increase in urban population and disposable income has created a strong demand for high-quality housing conditions in recent years. Recent research shows that urban residents increasingly prefer new housing with a larger area, better building quality, improved environment [41[41][42],42], and sufficient facilities such as advanced medical care and high-quality education resources [43]. According to the UN, China’s urbanization rate will continue to increase in the coming years and reach 70% by 2030. The need to improve urban living conditions in megacities will become even more pressing [44]. Such needs can no longer be fulfilled by the informal housing provided by urban villages [21]. However, high-quality formal housing remains extremely limited in Chinese megacities. For example, in 2007, Shenzhen boasted merely one million commercial, residential units. The number increased to 1.89 million in 2020, which can only accommodate a small portion of the urban residents living in this city. Although the municipal government has made efforts to provide public housing in recent years, the stock of developed public housing is very limited. One of the specific consequences of the urbanization and land reform processes that transpired in the 1980s is that a high percentage of land within the boundaries of megacities is occupied by urban villages [8,45][8][45]. The inner conditions of urban villages are often crowded and disordered [7]. Urban villages always have high-density and poor-quality buildings [46]. The surrounding environment of urban villages typically lacks high-quality infrastructure and public service [47], among others. In the earlier urban development stage, the presence of urban villages was critical because they served as sites of affordable housing and living space for the influx of urban migrants [48,49][48][49]. In terms of the demand side, the main driver of gentrification in the West is the desire to return to the city centre [50]. By contrast, the emerging needs of China’s urban dwellers are largely reflected in the urgent demand for better living conditions. With the rising income levels, urban residents have changed their preferences of living conditions and can afford better living. Most urban villages with sub-standard environments have failed to meet the new needs for improving living conditions [41]. The mismatch between the emerging demand and the unsatisfactory urban living conditions in urban villages becomes an essential problem in megacities. In such context, the redevelopment of urban villages into high-quality formal housing estates has become an important means to fulfil the emerging housing demands [24,51][24][51].2.2. Capital Accumulation and Developers’ Pursuit of Land-Related Investment Returns

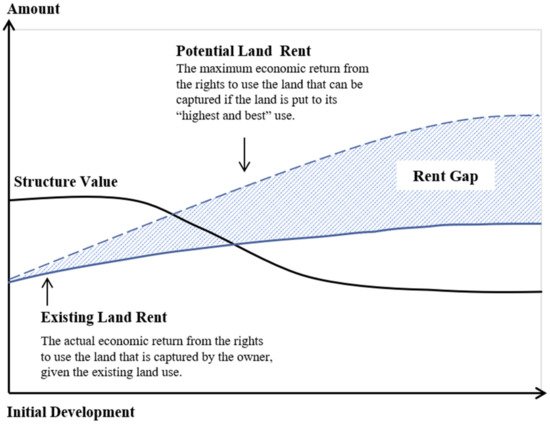

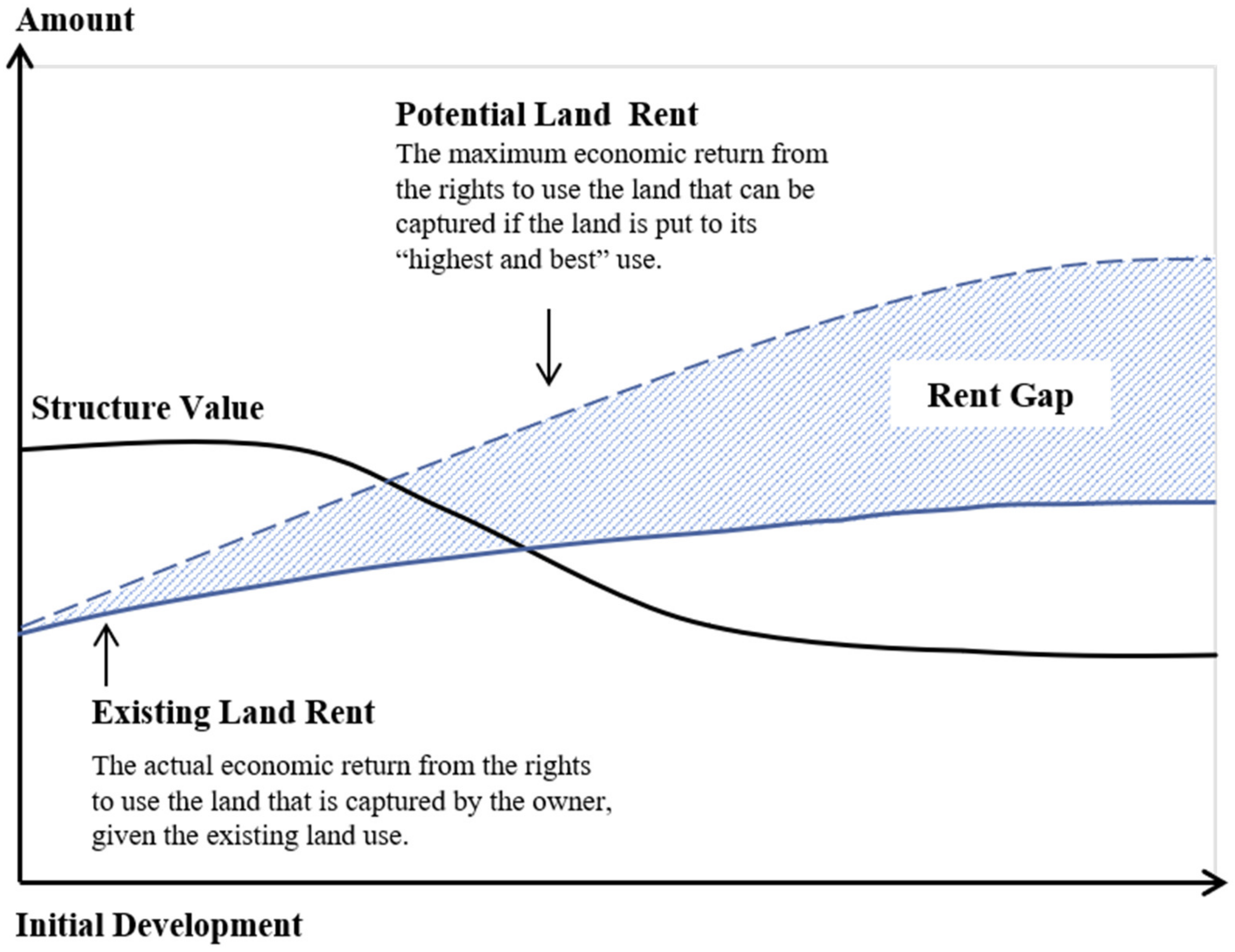

From the supply side, profit-oriented urban capital accumulation via land-related investment has become a key driver of spatial reproduction in the global urban depressed areas [52,53][52][53]. According to Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith [54], urban space is an important carrier to absorb capital appreciation. The reconfiguration of urban space has been heavily influenced by the rationale of capital accumulation which is now a symbolic representation of real estate values [55]. Accordingly, the land redevelopment process in urban renewal can be understood as a continuous spatial reproduction of urban depressed space [52], which is an important way to realize capital accumulation. A wealth of studies have investigated the vital role of capital accumulation in shaping the redevelopment process and outcomes in different local contexts [56,57][56][57]. According to Marxist geographer Neil Smith [58], the land rent gap is a fundamental concept to understanding land redevelopment from the perspective of capital accumulation. Specifically, the land rent gap denotes the difference between the financial returns generated by a property due to current land use and the probable returns caused if the property were put to more lucrative use. When this rent gap becomes sufficiently large for developers to reap significant investment returns from this process, redevelopment will occur. From this perspective, urban capital and developers in different countries have similar aims in relation to urban redevelopment activities, not least in respect of land-related investment returns. However, their roles and influence in this sphere may vary in accordance with difference in local renewal contexts [56,57][56][57]. With the reform of urban land system marked by the separation of the land use rights and state land ownership, a prosperous land market has been formed in China [59]. Capital accumulation and developers’ pursuit of land-related investment returns from the rent gap becomes a powerful force for urban village redevelopment in China [10,60,61][10][60][61]. The public infrastructure and planning policies during dynamic urbanization have substantially impacted the land rent gap. When the surrounding urban environment and infrastructure are improved, the potential rent of the urban village area keeps rising rapidly. By contrast, due to the suboptimal land use and disorganized physical environment [62], the existing land rent in urban villages has been low for a long time. The formation of land rent gap makes it profitable for developers to redevelop urban villages for “highest and best” use (Figure 52). According to previous literature, well-located urban villages, such as in large cities or close to urban centres, are supposed to experience earlier redevelopment in comparison to villages located in outlying zones [21,63][21][63]. However, a recent study shows that the land rent gap of urban villages is also affected by many other factors like land ownership and rights, existing land use, and planned land use. These factors collectively affected the land rent gap as well as the attributes of transaction costs in the redevelopment processes and shaped redevelopment outcomes [64]. On the one hand, capital accumulation and developers’ pursuit of land-related investment returns has promoted the demolition and rebuilding of urban villages and has contributed to many formal housing units via redevelopment [65]. On the other hand, market-oriented redevelopment of urban villages has brought some negative impacts to some vulnerable social groups and the city. Migrants have been forced to move out of urban villages. This phenomenon will inevitably threaten social sustainability in urban development [27,66][27][66].

Figure 52. Development of rent gap in urban villages.

Figure 52. Development of rent gap in urban villages.