| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Angeles Aroca | -- | 1501 | 2022-04-20 11:18:52 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | -1 word(s) | 1500 | 2022-04-21 03:37:56 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1500 | 2022-04-21 03:38:28 | | | | |

| 4 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1500 | 2022-04-22 03:47:11 | | |

Video Upload Options

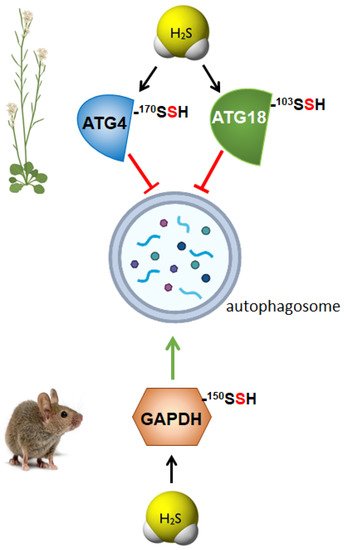

The term “autophagy”, (from the Greek words auto, meaning “self” and phagein, meaning “to eat”)—literally, eating one’s self—was first created by Christian de Duve over 40 years ago, who discovered lysosomes and provided clear proof of their participation in this process. It is an evolutionarily conserved process of degradation and recycling in eukaryotic organisms. The research of H2S as a signaling molecule has been focused on the effect of sulfide donors on different diseases and physiological pathways, until in 2009 when Snyder’s group described persulfidation or S-sulfhydration as the mechanism of H2S signaling. Since then, numerous targets have been identified to undergo persulfidation, and it has become recognized as the main mechanism by which H2S controls several cellular functions. Persulfidation is a posttranslational modification of cysteine residues, where a thiol group (RSH) is transformed into a persulfide group (RSSH)

1. Introduction

2. Regulation of Autophagy by Persulfidation in Plants

3. Regulation of Autophagy by Persulfidation in Animals

References

- Deter, R.L.; De Duve, C. Influence of glucagon, an inducer of cellular autophagy, on some physical properties of rat liver lysosomes. J. Cell Biol. 1967, 33, 437–449.

- Marshall, R.S.; Vierstra, R.D. Autophagy: The Master of Bulk and Selective Recycling. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 173–208.

- Avin-Wittenberg, T. Autophagy and its role in plant abiotic stress management. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1045–1053.

- Gou, W.; Li, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Xie, Q. Autophagy in Plant: A New Orchestrator in the Regulation of the Phytohormones Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2900.

- Feng, Y.; He, D.; Yao, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 24–41.

- Parzych, K.R.; Klionsky, D.J. An overview of autophagy: Morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 460–473.

- van Doorn, W.G.; Papini, A. Ultrastructure of autophagy in plant cells. Autophagy 2013, 9, 1922–1936.

- Lescat, L.; Véron, V.; Mourot, B.; Péron, S.; Chenais, N.; Dias, K.; Riera-Heredia, N.; Beaumatin, F.; Pinel, K.; Priault, M.; et al. Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy in the Light of Evolution: Insight from Fish. J. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 2887–2899.

- Melia, T.J.; Lystad, A.H.; Simonsen, A. Autophagosome biogenesis: From membrane growth to closure. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219.

- Tsukada, M.; Ohsumi, Y. Isolation and characterization of autophagy-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 1993, 333, 169–174.

- Ravanan, P.; Srikumar, I.F.; Talwar, P. Autophagy: The spotlight for cellular stress responses. Life Sci. 2017, 188, 53–67.

- Matsui, Y.; Takagi, H.; Qu, X.; Abdellatif, M.; Sakoda, H.; Asano, T.; Levine, B.; Sadoshima, J. Distinct Roles of Autophagy in the Heart During Ischemia and Reperfusion. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 914–922.

- Levine, B.; Mizushima, N.; Virgin, H.W. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 2011, 469, 323–335.

- Nah, J.; Yuan, J.; Jung, Y.K. Autophagy in neurodegenerative diseases: From mechanism to therapeutic approach. Mol. Cells 2015, 38, 381–389.

- Chen, L.; Su, Z.-Z.; Huang, L.; Xia, F.-N.; Qi, H.; Xie, L.-J.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Q.-F. The AMP-Activated Protein Kinase KIN10 Is Involved in the Regulation of Autophagy in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1201.

- Signorelli, S.; Tarkowski, Ł.P.; Van den Ende, W.; Bassham, D.C. Linking Autophagy to Abiotic and Biotic Stress Responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 413–430.

- Üstün, S.; Hafrén, A.; Hofius, D. Autophagy as a mediator of life and death in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 40, 122–130.

- Gotor, C.; Garcia, I.; Crespo, J.L.; Romero, L.C. Sulfide as a signaling molecule in autophagy. Autophagy 2013, 9, 609–611.

- Aroca, A.; Benito, J.M.; Gotor, C.; Romero, L.C. Persulfidation proteome reveals the regulation of protein function by hydrogen sulfide in diverse biological processes in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 4915–4927.

- Jurado-Flores, A.; Romero, L.C.; Gotor, C. Label-Free Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Nitrogen Starvation in Arabidopsis Root Reveals New Aspects of H2S Signaling by Protein Persulfidation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 508.

- Laureano-Marín, A.M.; Aroca, A.; Perez-Perez, M.E.; Yruela, I.; Jurado-Flores, A.; Moreno, I.; Crespo, J.L.; Romero, L.C.; Gotor, C. Abscisic Acid-Triggered Persulfidation of the Cys Protease ATG4 Mediates Regulation of Autophagy by Sulfide. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 3902–3920.

- Álvarez, C.; Garcia, I.; Moreno, I.; Perez-Perez, M.E.; Crespo, J.L.; Romero, L.C.; Gotor, C. Cysteine-generated sulfide in the cytosol negatively regulates autophagy and modulates the transcriptional profile in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4621–4634.

- Laureano-Marín, A.M.; Moreno, I.; Aroca, Á.; García, I.; Romero, L.C.; Gotor, C. Regulation of Autophagy by Hydrogen Sulfide. In Gasotransmitters in Plants: The Rise of a New Paradigm in Cell Signaling; Lamattina, L., García-Mata, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 53–75.

- Aroca, A.; Yruela, I.; Gotor, C.; Bassham, D.C. Persulfidation of ATG18a regulates autophagy under ER stress in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023604118.

- Dove, S.K.; Piper, R.C.; McEwen, R.K.; Yu, J.W.; King, M.C.; Hughes, D.C.; Thuring, J.; Holmes, A.B.; Cooke, F.T.; Michell, R.H.; et al. Svp1p defines a family of phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate effectors. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1922–1933.

- Wun, C.-L.; Quan, Y.; Zhuang, X. Recent Advances in Membrane Shaping for Plant Autophagosome Biogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 565.

- Iqbal, I.K.; Bajeli, S.; Sahu, S.; Bhat, S.A.; Kumar, A. Hydrogen sulfide-induced GAPDH sulfhydration disrupts the CCAR2-SIRT1 interaction to initiate autophagy. Autophagy 2021, 17, 3511–3529.

- Mustafa, A.K.; Gadalla, M.M.; Sen, N.; Kim, S.; Mu, W.; Gazi, S.K.; Barrow, R.K.; Yang, G.; Wang, R.; Snyder, S.H. H2S Signals Through Protein S-Sulfhydration. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, ra72.

- Jarosz, A.P.; Wei, W.; Gauld, J.W.; Auld, J.; Özcan, F.; Aslan, M.; Mutus, B. Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH) Is Inactivated by S- Sulfuration in Vitro. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 512.

- Aroca, A.; Serna, A.; Gotor, C.; Romero, L.C. S-sulfhydration: A cysteine posttranslational modification in plant systems. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 334–342.

- Aroca, A.; Schneider, M.; Scheibe, R.; Gotor, C.; Romero, L.C. Hydrogen Sulfide Regulates the Cytosolic/Nuclear Partitioning of Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase by Enhancing its Nuclear Localization. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 983–992.

- Krishnan, N.; Fu, C.; Pappin, D.J.; Tonks, N.K. H2S-Induced sulfhydration of the phosphatase PTP1B and its role in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Sci. Signal. 2011, 4, ra86.

- Yadav, V.; Gao, X.H.; Willard, B.; Hatzoglou, M.; Banerjee, R.; Kabil, O. Hydrogen sulfide modulates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) phosphorylation status in the integrated stress-response pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13143–13153.