| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Claudia Juliano | -- | 4170 | 2022-04-15 08:29:06 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | -63 word(s) | 4107 | 2022-04-15 09:36:46 | | | | |

| 3 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 4107 | 2022-05-26 05:59:59 | | |

Video Upload Options

Skin lightening is defined as "the practice of using chemicals or any other product with depigmenting potential in an attempt to lighten skin tone or improve the complexion; these goals are achieved by decreasing the concentration of melanin to achieve a reduction in the physiological pigmentation of the skin". Products used to achieve this purpose are known as depigmenting, skin-lightening, skin-bleaching, skin-brightening or skin-evening agents. Skin-whitening products containing highly toxic active ingredients (in particular mercury derivatives, hydroquinone and corticosteroids) are easily found on the market; the use of these depigmenting agents can be followed by a variety of adverse effects, with very serious and sometimes fatal complications, and is currently an emerging health concern in many countries.

1. Introduction

|

Skin Lightening Agents |

Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|

|

Hydroquinone, Azelaic acid, Ellagic acid, Kojic acid, Mequinol, Arbutin, Flavonoids, Resveratrol, N-acetyl glucosamine |

Inhibition of tyrosinase activity [9] |

|

Alpha-hydroxy acids, salicylic acid |

Acceleration of epidermal turnover [9] |

|

Retinoids |

Inhibition of tyrosinase transcription, epidermal melanin dispersion [8] |

|

Vitamin C, Vitamin E |

Antioxidant action, acceleration of epidermal turnover [9] |

|

Niacinamide, Soy proteins, Linoleic acid |

2. Colourism and the Widespread Practices of Skin-Lightening

3. Toxic Ingredients in Skin Lightening Cosmetics

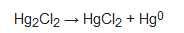

Mercury

4. Hydroquinone

5. Corticosteroids

References

- Pillaiyr, T.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Downregulation of melanogenesis: Drug discovery and therapeutic options. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 282–298.

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. Quantitative analysis of eumelanin and pheomelanin in human, mice, and other animals: A comparative review. Pigment Cell Res. 2003, 16, 523–531.

- Takeuchi, S.; Zhang, W.; Wakamatsu, K.; Ito, S.; Hearing, V.J.; Kraemer, K.H.; Brash, D.E. Melanin acts as a potent UVB photosensitizer to cause an atypical mode of cell death in murine skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15076–15081.

- Agar, N.; Young, A.R. Melanogenesis: A photoprotective response to DNA damage? Mutat. Res. 2005, 571, 121–132.

- Nordin, F.N.M.; Aziz, A.; Zakaria, Z.; Radzi, C.W.J.W.M. A systematic review on the skin whitening products and their ingredients for safety, health risk and the halal status. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 20, 1050–1060.

- Davids, L.M.; van Wyk, J.; Khumalo, N.P.; Jablonski, N.G. The phenomenon of skin lightening: Is it right to be light? S. Afr. J. Sci. 2016, 112, 11–12.

- Eagle, L.; Dahl, S.; Low, D.R. Ethical issues in the marketing of skin lightening products. In Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference ANZMAC, Brisbane, Australia, 1–3 December 2014; pp. 75–81.

- Burger, P.; Landreau, A.; Azoulay, S.; Michel, T.; Fernandez, X. Skin whitening cosmetics: Feedback and challenges in the development of natural skin lighteners. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 36.

- Couteau, C.; Coiffard, L. Overview of skin whitening agents: Drugs and cosmetic products. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 27.

- Hu, Y.; Zeng, H.; Huang, J.; Jiang, L.; Chen, J.; Zeng, Q. Traditional Asian herbs in skin whitening; The current development and limitations. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 982.

- Opperman, L.; De Kock, M.; Klaasen, J.; Rahiman, F. Tyrosinase and melanogenesis inhibition by indigenous African plants: A review. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 60.

- Naidoo, L.; Khoza, N.; Dlova, N.C. A fairer face, a fairer tomorrow? A review of skin lighteners. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 33.

- Million Insights. Skin Lightening Products Market Analysis Report by Product, by Nature, by Region and Segment Forecasts from 2019 to 2025. 2020. Available online: https://www.millioninsights.com/industry-reports/global-skin-lightening-products-market (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- Benn, E.K.T.; Alexis, A.; Mohamed, N.; Wang, Y.-H.; Khan, I.A.; Liu, B. Skin bleaching and dermatological health of African and Afro-Caribbean populations in the US; new directions for methodologically rigorous, multidisciplinary, and culturally sensitive research. Dermatol. Ther. 2016, 6, 453–459.

- Pollock, S.; Taylor, S.; Oyerinde, O.; Nurmohamed, S.; Dlova, N.; Sarkar, R.; Galadari, H.; Manela-Azulai, M.; Chung, H.S.; Handog, E.; et al. The dark side of skin lightening: An international collaboration and review of a public health issue affecting dermatology. Int. J. Women Dermatol. 2021, 7, 158–164.

- Li, E.P.H.; Min, H.J.; Belk, R.W.; Kimura, J.; Bahl, S. Skin Lightening and Beauty in Four Asian Cultures. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Lee, A.Y., Soman, D., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2008; Volume 35, pp. 444–449.

- Shevde, N. All’s Fair in Love and Cream: A cultural case study of Fair & Lovely in India. Advert. Soc. Rev. 2008, 9, 1–9.

- Shroff, H.; Diedrichs, P.C.; Craddock, N. Skin color, cultural capital, and beauty products: An investigation of the use of skin fairness products in Mumbai, India. Front. Public Health 2018, 5, 365.

- Porcheron, A.; Latreille, J.; Jdid, R.; Tschachler, E.; Morizot, F. Influence of skin ageing features on Chinese women’s perception of facial age and attractiveness. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2014, 36, 312–320.

- Dadzie, O.E.; Petit, A. Skin bleaching: Highlighting the misuse of cutaneous depigmenting agents. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2009, 23, 741–750.

- Gbetoh, M.H.; Amyot, M. Mercury, hydroquinone and clobetasol propionate in skin lightening products in West Africa and Canada. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 403–410.

- Ricketts, P.; Knight, C.; Gordon, A.; Boischio, A.; Voutchkov, M. Mercury exposure associated with use of skin lightening products in Jamaica. J. Health Pollut. 2020, 10, 200601.

- Chen, J.; Ye, Y.; Ran, M.; Li, Q.; Ruan, Z.; Jin, N. Inhibition of Tyrosinase by Mercury Chloride: Spectroscopic and Docking Studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 81.

- Park, J.-D.; Zheng, W. Human exposure and health effects of inorganic and elemental mercury. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2012, 45, 344–352.

- Abbas, H.H.; Sakakibara, M.; Sera, K.; Andayanie, E. Mercury exposure and health problems of the students using skin-lightening cosmetic products in Makassar, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 58.

- Chan, T.Y.K. Inorganic mercury poisoning associated with skin-lightening cosmetic products. Clin. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 886–891.

- Copan, L.; Fowles, J.; Barreau, T.; McGee, N. Mercury toxicity and contamination of households from the use of skin creams adulterated with mercurous chloride (calomel). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 10943–10954.

- Loretz, L.J.; Api, A.M.; Barraj, L.M.; Burdickd, J.; Dressler, W.E.; Gettings, S.D.; Han Hsu, H.; Pan, Y.H.L.; Re, T.A.; Renskers, K.J.; et al. Exposure data for cosmetic products: Lipstick, body lotion, and face cream. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005, 43, 279–291.

- Hamann, C.R.; Boonchai, W.; Wen, L.; Nishijima Sakanashi, E.; Chu, C.-Y.; Hamann, K.; Hamann, C.P.; Sinniah, K.; Hamann, D. Spectrometric analysis of mercury content in 549 skin-lightening products: Is mercury toxicity a hidden global health hazard? J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 281–287.

- McRill, C.; Boyer, L.V.; Flood, T.J.; Ortega, L. Mercury toxicity due to the use of a cosmetic cream. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2000, 42, 4–7.

- Weldon, M.M.; Smolinski, M.S.; Maroufi, A.; Hasty, B.W.; Gilliss, D.; Boulanger, L.; Balluz, L.; Dutton, R.J. Mercury poisoning associated with a Mexican beauty cream. West. J. Med. 2000, 173, 15–18.

- Sastri, M.N.; Kalidas, C. Photochemical estimation of mercuric chloride by Eder’s reaction with ceric ion as sensitizer. Fresenius Z. Anal. Chem. 1955, 148, 3–6.

- Awitor, K.O.; Bernard, L.; Coupat, B.; Fournier, J.P.; Verdier, P. Measurement of mercurous chloride vapor pressure. New J. Chem. 2000, 24, 399–401.

- Ladizinski, B.; Mistry, N.; Kundu, R.V. Widespread use of toxic skin lightening compounds: Medical and psychosocial aspects. Dermatol. Clin. 2011, 29, 111–123.

- Engler, D.E. Mercury “bleaching” creams. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 52, 1113–1114.

- Murerva, R.; Gwala, F.; Amuti, T.; Muange, M. Childhood effects of pre-natal and post-natal exposure to mercurial skin lightening agents. Literature review. Int. J. Med. Stud. 2022; in press.

- Peregrino, C.P.; Moreno, M.V.; Miranda, S.V.; Rubio, A.D.; Leal, L.O. Mercury levels in locally manufactured Mexican skin-lightening creams. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 2516–2523.

- Agorku, E.S.; Kwaansa-Ansah, E.E.; Voegborlo, R.B.; Amegbletor, P.; Opoku, F. Mercury and hydroquinone content of skin toning creams and cosmetic soaps, and the potential risks to the health of Ghanaian women. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 319.

- Jimbow, K.; Obata, H.; Pathak, M.A.; Fitzpatrick, T.B. Mechanism of depigmentation by hydroquinone. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1974, 62, 436–449.

- Aspengren, S.; Norström, E.; Wallin, M. Effects of hydroquinone on cytoskeletal organization and intracellular transport in cultured Xenopous laevis melanophores and fibroblasts. ISRN Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 524781.

- Gandhi, V.; Verma, P.; Naik, G. Exogenous ochronosis after prolonged use of topical hydroquinone (2%) in a 50-year-old Indian female. Indian J. Dermatol. 2012, 57, 394–395.

- Bhattar, P.A.; Zawar, V.P.; Godes, K.V.; Patil, S.P.; Nadkarni, N.J.; Gautam, M.M. Exogenous ochronosis. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 537–543.

- Nordlund, J.J.; Grimes, P.E.; Ortonne, J.P. The safety of hydroquinone. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2006, 20, 781–787.

- Addo, H.A. Squamous cell carcinoma associated with prolonged bleaching. Ghana Med. J. 2000, 34, 144–146.

- Ly, F.; Kane, A.; Déme, A.; Ngoh, N.-F.; Niang, S.-O.; Bello, R.; Rethers, L.; Dangou, J.-M.; Dieng, M.-T.-D.; Diousse, P.; et al. First case of squamous cell carcinoma associated with cosmetic use of bleaching compounds. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 137, 128–131.

- Gbandama, K.K.P.; Diabaté, A.; Kouassi, K.A.; Kouassi, Y.I.; Allou, A.-S.; Kaloga, K. Squamous cell carcinoma associated with cosmetic use of bleaching agents: About a case in Ivory Coast. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2019, 11, 322–326.

- Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on Classification, Labelling and Packaging of Substances and Mixtures, Amending and Repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and Amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32008R1272&from=EN (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Ahluwalia, A. Topical glucocorticoids and the skin-mechanisms of action: An update. Mediat. Inflamm. 1998, 7, 183–193.

- Olumide, Y.M.; Akinkugbe, A.O.; Altraide, D.; Mohammed, T.; Ahamefule, N.; Ayanlowo, S.; Onyekonwu, C.; Essen, N. Complications of chronic use of skin lightening cosmetics. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008, 47, 344–353.

- Dey, V.K. Misuse of topical corticosteroids: A clinical study of adverse effects. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2014, 5, 436–440.

- Sendrasoa, F.A.; Ranaivo, I.M.; Andrianarison, M.; Raharolahy, O.; Razanakoto, N.H.; Ramarozatovo, L.S.; Rapelanoro Rabenja, F. Misuse of topical corticosteroids for cosmetic purpose in Antananarivo, Madagascar. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9637083.

- Bezzina, C.; Bondon-Guitton, E.; Montastruc, J.L. Inhaled corticosteroid-induced hair depigmentation in a child. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2013, 12, 119–120.