1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2016, nearly 2 billion adults were overweight, of which more than 650 million were obese

[1]. Obesity is common in both developed and developing countries, affecting all ages without distinguishing social classes

[2][3]. Over the past 50 years, overweight and obesity have risen sharply. In 2016, the United Stated of America and Saudi Arabia registered the highest percentage of obese adults, 36.2% and 35.4%, respectively. Conversely, Vietnam, Japan, Ethiopia, and India had the lowest percentages of obese adults in 2016

[1]. Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation typically resulting in negative health impacts. Although there is a genetic predisposition to developing obesity, the causes of this disease are multifactorial. Thus, the complex interactions between epigenetics, lifestyle, cultural and environmental influences play a fundamental role in the development of obesity (

Figure 1)

[3][4][5]. Additionally, economic growth, social changes, and the global nutritional transition are seen as contributing to this epidemic

[6]. Obesity should not be seen only as a problem associated with physical image since people with excessive weight tend to have a higher risk of developing other comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and certain types of cancer, namely breast, ovary, liver, colon, and prostate

[2]. Obesity is also a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, chronic respiratory diseases, and osteoarthritis, which contribute to more than half of all deaths. More serious cases of obesity are associated with an increasing incidence of diseases such as asthma, gallstones, steatohepatitis, glomerulosclerosis, dyslipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction

[7]. The list of health consequences is extensive, and in addition to affecting quality of life, it also contributes to a higher risk of premature death

[8]. In the last two decades, the need to develop new therapies increased significantly. The physiological treatment forces the patient to make changes in diet and behavior, which is not always feasible due to the patient’s lack of motivation. Thus, the pharmacological approach is more attractive. Currently, pharmacological therapy includes the use of synthetic drugs

[9], although the demand for natural substances that have fewer side effects is increasing. To determine the effectiveness of new drugs or promising natural compounds, these potential therapies must be first evaluated in preclinical models (in vitro and in vivo) and later clinically

[10]. Cell cultures are important for obtaining information on the pharmacodynamics of compounds; however, more complex interactions, which are those that contribute to the pathophysiology of obesity, are not noticeable. Therefore, preclinical models, specifically animal models, are essential for identifying and validating pharmacological targets

[11]. Animal models for studying obesity comprise a variety of species, from non-mammals (zebrafish,

Caenorhabditis elegans and

Drosophila) to mammals (rodents, large animals, and non-human primates)

[7]. Within these animal models, small rodents (rats and mice) are the most widely used. Their cost-effectiveness and multiparity, physiology close to humans, and easy genetic manipulation are some of the advantages that make them the model of excellence

[7]. In this entry, researchers describe some of the most commonly used rodent models of research on obesity.

Figure 1. Risk factors of obesity.

2. Rodent Models of Obesity

The use of animals for scientific purposes is a long-standing practice, dating back to ancient Greece

[11][12]. Both humans and other mammals are highly complex organisms, where the organs perform different physiological functions in a regulated way. The anatomical and physiological similarities between human and animal, particularly mammal, led to the use of animals before applying new compounds on humans. To select an animal model, certain parameters must be met: pathophysiological similarities with the human disease; phenotypic correspondence with disease status; simplicity; replicability, reproducibility, and cost-efficiency

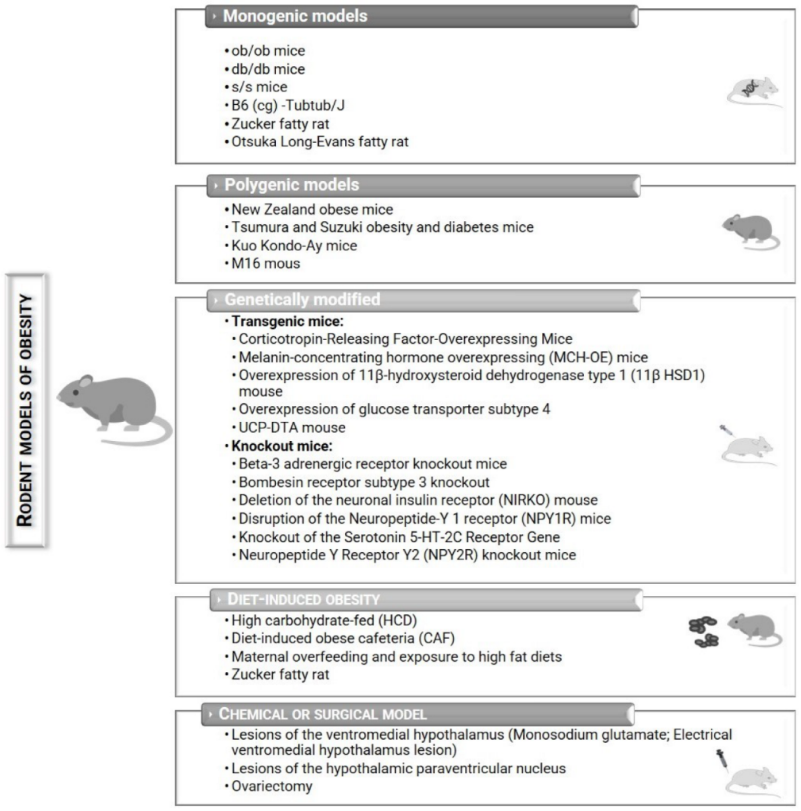

[11]. Rats and mice are the most widely used preclinical animal models to study obesity

[13][14][15]. These animal models help researchers to understand the biopathology and develop possible preventions and treatments against obesity (

Figure 2)

[14][16]. Nevertheless, each model presents its advantages and disadvantages (

Table 1).

Figure 2. Potential rodent models that can be used to study obesity.

Table 1. Main advantages and disadvantages of murine monogenic, polygenic, genetically modified, diet-induced, chemically induced, and surgically induced models of obesity.

| Models |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| Monogenic |

-

Identification of specific genes and their role in the regulation of energy balance

-

Effective and reliable model

-

Well-organized molecular map

|

-

Does not allow to create a successful drug for obesity since food-intake behavior is controlled by more than a single molecular target

-

Targeting specific molecular targets leads to undesired collateral effects

-

Energy partitioning and fat deposition different from humans

-

Do not represent human obesity diseases

|

| Polygenic |

|

|

| Genetically modified |

|

|

| Diet-induced |

-

Are more representative of human obesity diseases

-

Combines genetics and dietary influences

-

Mimics the gradual weight gain that occurs in the human population

|

|

| Chemical or surgical |

|

|

Based on Barrett et al.

[13] and Suleiman et al.

[17].

2.1. Monogenic Models

Monogenic animal models are animals with a single gene disorder. They are widely used to study obesity, very reliable, and effective. These models present a well-organized molecular map. However, they differ from humans in the way that they undertake their energy partitioning and fat deposition; and are generally not a good representative of human diseases

[17]. Although it has been proven that a single manipulation of almost 250 genes can induce obesity in mice, monogenic models are mainly a result from mutation(s) in the leptin pathway

[5][17]. Genetic manipulations or environmental/dietary factors will dictate the severity of obesity and comorbid metabolic modifications

[5].

2.1.1. ob/ob Mice

The obese mice (

ob/ob mice) were discovered in 1949 by investigators from the Jackson Laboratory

[6]. However, only in 1994 was the genetic characterization of this mutation as a single base pair deletion performed and the gene product was called leptin

[6][14][18]. This mutation prevents the secretion of bioactive leptin by positional cloning, causing its synthesis to be terminated prematurely

[6][7]. Leptin is an adipocyte-derived hormone, the major function of which is related to food intake inhibition, metabolism, and reproduction, through interaction with the central nervous system mainly relating to the hypothalamus. The normal function of the leptin pathway is required for body weight and energy homeostasis

[19][20][21]. Mutations in the leptin gene lead to animals with an obese phenotype

[14].

The

ob/ob mice are widely used because they display early-onset obesity, which is the result of hyperphagia and low energy expense

[7][22]. This obesity model possesses the capacity to gain weight in a short period of time, eventually reaching three times the normal weight of wild-type controls

[6][22]. These mice exhibit impaired glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, most likely as a secondary effect of obesity. Furthermore, they have high levels of circulating corticosterone, develop hypothyroidism, dyslipidemia, decreased body temperature, defective thermogenesis, and are infertile due to hypogonadism

[23]. The ob/ob mice have been used to evaluate the influence of several natural compounds on the obesity development

[24][25][26][27][28] as well as other concomitant diseases such as metabolic syndromes

[29] and oxidative stress

[30][31].

2.1.2. db/db Mice

The

db/db mouse (db stands for diabetes)

[6] is another option for studying the molecular basis of obesity but is commonly used for the investigation on type 2 diabetes

[17]. These db/db mice were also developed by investigators from the Jackson Laboratories in 1966 and are phenotypically similar to the ob/ob mice model. They exhibit a mutation in the leptin receptor gene, in an autosomal recessive trait that encodes for a G-to-T point mutation, leading to defective leptin signaling

[7][17]. The db/db mice are characterized by hyperphagia, a consequence of impaired leptin signing in the hypothalamus, develop early-onset obesity due to low energy expenditure, are insulin resistant, have decreased insulin levels, and are hypothermic. They also have slow growth due to growth hormone deficiency and are infertile

[6][7][14][17][32]. Comparatively to the

ob/ob mouse, the

db/db model has a marked resistance to leptin, which is a consequence of a mutated leptin receptor, but its leptin levels are markedly elevated

[14]. The db/db model can be used in the comprehensive study of diabetes and to evaluate the effect of natural compounds on disease development or as chemopreventive agents

[33][34][35][36].

2.1.3. s/s Mice

The

s/s mice were developed by Bates and collaborators (2003) to study the role of individual leptin signals, by disturbing the STAT3 pathway, even though it is regularly expressed on the cell surface and can mediate other leptin signals. In this model, the long-form signaling pathways by which leptin exerts its functions are compromised

[17][18][37]. The

s/s mice are hyperphagic and obese, present normal body length, and contrarily to the

ob/ob or the

db/db models, they are fertile

[14]. The db/db mice and

s/s mice are often compared, and share some characteristics such as early development of obesity, hyperphagia, and high leptin/insulin levels

[23]. The improvement verified in

s/s mice regarding glucose homeostasis is due to decreased insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. These facts are usually attributed to leptin mediation by STAT3, via melanocortin signaling, which affects body energy homeostasis. However, fertility, body growth, and glucose homeostasis are controlled through non-STAT3 signaling

[14][38]. The transgenic

s/s mouse has played its contribution to the research on obesity and diabetes

[18].

2.2. Polygenic Models

For the study of obesity, polygenic models provide more accurate information about the biology of obesity, when compared to monogenic models, since human obesity is mediated by multiple genes

[6]. These models are some of the most used, are cost-effective, used regularly, and are considered more realistic models for studying human obesity. Among the different types of polygenic models, only the most frequently used models are included in this entry

[17].

2.2.1. New Zealand Obese Mice

The New Zealand obese mice (NZO) strain is a polygenic model that develops obesity and type 2 diabetes only in males

[6][7][39]. This mouse strain was obtained in the Hugh Adam Department of Cancer from the selective inbreeding of a stock colony

[40]. Some gene variants involved in obesity and diabetes in NZO mice are the

Tbc1d1 gene inactivation, causing enhanced transport and oxidation of fatty acids which in turn reduces glucose transport, and the transcription factor

Zfp69, which is associated with altered triglyceride distribution and enhanced diabetes susceptibility

[41][42]. Leptin receptor (

Lepr), phosphatidyl choline transfer protein (

Pctp), ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (

Abcg1), and neuromedin U receptor 2 (

Nmur2) are other candidates potentially contributing to the polygenic obesity and diabetes of NZO mice

[41][42]. These animals show the highest levels of adiposity among the polygenic models. They also share other characteristics that are similar to human type 2 diabetes, such as insulin resistance in brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle at the age of 4–5 weeks old, that progress into diabetes. They show hypercholesterolemia and hypertension

[7][43]. They display moderate hyperphagia and reduced energy expenditure and voluntary activity

[7], especially when compared to control or even

ob/ob mice

[6][17][43]. This strain is similar to the

ob/ob mice, except for its ability to maintain body temperature during a 20 h period of cold temperatures, whereas

ob/ob mice would not be able to surpass a temperature of 4 °C

[43]. NZO mice fed a high-fat diet develop liver steatosis, which is associated with a loss of autophagy efficiency that leads to the disturbance of proteostasis

[44].

2.3. Genetically Modified Mice

Genetically modified mice are widely used in research to study genetic influence, modulate a disease, or analyze a biological process in vivo. Mice are considered to be the most suitable mammals for this purpose, as they share the same organ and tissue systems as humans

[45]. Genetically models of obesity include transgenic and knockout mice.

2.3.1. Transgenic Mice

Transgenic models of obesity were created to promote access to animals with genetic characteristics identical to those described in obese humans

[17].

Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Overexpressing Mice

The corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) is a peptide that acts as a neuroendocrine hormone and neurotransmitter through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and hypothalamic and extrahypothalamic neuronal pathways

[46]. CRF induces a rapid decrease in food intake and gastric emptying that leads to stress-related alterations in food intake and the gastric motor function. Hormones related to the pattern of eating, such as the neuropeptide Y and leptin, are also regulated by CRF

[46]. The CRF-overexpressing mice exhibit truncal obesity, muscle wasting, thin skin and hair loss, and are commonly used for study conditions associated with hyperadrenocorticism such as Cushing’s syndrome

[14]. This mouse model is often used for studies regarding the response to different feeding conditions

[46][47] and studies related to chronic stress

[48][49].

Melanin-Concentrating Hormone Overexpressing (MCH-OE) Mice

The melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH) is a hypothalamic peptide known for its role in the regulation of energy balance and feeding behavior

[50][51]. MCH is also modulated in response to leptin and insulin

[52]. The MCH-OE mice become obese, and display hyperphagia, hyperinsulinemia, and are insulin resistant when exposed to a high-fat diet (HFD)

[14][53]. MCH-OE mice are commonly used to study the effects of different feeding behaviors on obesity and insulin resistance

[50][52][54].

2.3.2. Knockout Mice

Knockout mice are a valuable tool used to explore potential strategies for the treatment of specific diseases, that includes pharmacological and genetic therapy approaches. Another major purpose of these mice models is to understand the function and significance of specific genes. They are an excellent tool for producing a model of human disease and to evaluate the physiological functions of specific genes

[55].

Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor Knockout Mice

In rodents, the β-3 adrenergic receptors (β3-ARs) are largely expressed in the white and brown adipose tissue

[53][56][57]. β3-ARs are linked to the control of thermogenesis in brown adipocytes and stimulation of lipolysis in white adipocytes, through activation of the sympathetic nervous system

[56]. The β3-AR knockout mice are moderately obese, a phenotype that is more common in females. Since food intake is similar to the control groups, changes are considered to be due to a decrease in activity of the sympathetic nervous system

[14][53]. This mouse model can be helpful for the study of selectivity and function of β3-AR ligands and may present as an important model to distinguish physiology mediated by the sympathetic nervous system

[53].

Bombesin Receptor Subtype 3 Knockout Mice

The bombesin-like peptides bind to G protein coupled receptors, such as gastrin releasing peptide receptor (GRP-R), neuromedin B receptor (NMB-R), and bombesin receptor subtype 3 (BRS-3). Bombesin-like peptides are found throughout the entire central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract and its main functions are the modulation of smooth-muscle contraction, exocrine and endocrine processes, metabolism, and behavior

[53]. BRS-3 in both melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R)- and single-minded homolog 1 (SIM1)-expressing neurons contributes to the regulation of food intake, body weight, adiposity, body temperature, and insulin sensitivity

[58]. The BRS-3 knockout leads to mild obesity, hypertension, impaired glucose metabolism, reduced metabolic rates, increased feeding efficiency, and hyperphagia

[59][60]. This mouse model is a great option for the study of moderate obesity, related with type-2 diabetes

[53][60].

2.4. Chemical or Surgical Models of Obesity

The hypothalamus, despite its numerous functions, plays a fundamental role in the transmission of afferent signals from the intestine and brain stem, as well as in the processing of efferent signals that modulate food intake and energy expenditure. It is subdivided into nuclei connected to each other, of which the arcuate nucleus (ARC), paraventricular nucleus (PVN), ventromedial nucleus (VMN), dorsomedial nucleus (DMN), and lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) stand out

[61]. The lesions produced in these nuclei can be obtained mechanically, through surgery, radiofrequency or electrolytically, or chemically using neuronal toxins such as monosodium glutamate, gold thioglucose, kainic acid, ibotenic acid, and bipiperidyl mustard

[53]. Medial hypothalamic lesions (ARC, VMN, and DMN) are associated with strong hyperphagia and activation of the TLR4/NF-κB-pathway, as well as reduced expression of oxytocin in the hypothalamus

[62]. Surgical removal of the ovaries is also used to study the incidence of obesity in women.

2.4.1. Lesions of the Ventromedial Hypothalamus

The ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) nucleus, located in the hypothalamus, is a very complex and important nucleus, which receives several inputs that project to the brain stem and spinal cord, and is associated with the regulation of eating behavior and satiety. One of the first models developed to induce obesity in rodents used rats with lesions in the ventromedial region of the mediobasal hypothalamus (VMH lesions)

[7][14][29]. VMH lesion further exaggerates insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in rats fed a sucrose diet, with males being more prone to this exacerbation

[63]. Bilateral lesions of the VMH could be made using electrical current or the neurotoxin monosodium glutamate (MSG), leading to the development of hyperphagia, vagal hyperactivity, sympathetic hypoactivity, enlarged pancreatic islets, and hyperinsulinemia

[10][64]. Obesity can develop in these animals even when food intake is restricted, although the mechanism by which hypothalamic injury induces obesity is still unknown

[14][53]. Nevertheless, the nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1), exclusively expressed in the VMH region of the brain, seems to be a key component in the VMH-mediated regulation of energy homeostasis, playing a protective role against metabolic stressors including aging and high-fat diets

[65].

Monosodium Glutamate (MSG)

MSG is a neurotoxin that can be administered subcutaneously or i.p. (2–4 mg/g of body weight) during the neonatal period, for 4–10 times to obtain obesity. It is a substance that can be found in many foods and therefore the effects of this substance when taken orally have been studied

[10][66]. The administration of MSG in rats or mice will induce vagal hyperactivity and sympathetic-adrenal hypoactivity, which will result in obesity, due to the lack of control between nutrient absorption and energy expenditure. The administration of this neurotoxin induces changes related to the lack of control of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis with dose-dependent curve, including hypophagia, development of obesity, hypoactivity, late puberty, reduced ovaries weight, and elevated serum levels of corticosteroids

[66]. In addition, the levels of glucose, triglycerides, and leptin are also increased, resulting in an increase in white adipose tissue deposition and insulin resistance. Adult rats who received MSG in the neonatal period developed endocrine dysfunction syndromes which is characterized by obesity development, disturbances in the regulation of caloric balance, reduced growth, behavioral changes, and hypogonadism

[10][67].

2.5. Diet-Induced Obesity (DIO)

Animal models of diet-induced obesity (DIO) are useful for studying the polygenic causes of obesity since they allow to reproduce the most common cause of this disease in man: dietary imbalances

[7][10][16][68][69]. Animals, usually laboratory rodents (rats and mice), are exposed to specifically tailored diets that induce obesity. These diets should be prepared by companies that are aware of the nutritional specificities of laboratory animals, modifying their formulation in accordance with the objectives of each researcher

[11]. Additionally, different diets could be used such as a high-fat diet (HFD), high-sugar diet (HSD), and the combination of the last two, called Western diets

[15][69]. The diet, especially in Western countries, is rich in saturated fat and carbohydrates such as fructose and sucrose, and when given to animals it allows them to mimic the signs and symptoms that are characteristic of human metabolic syndrome

[70]. Nevertheless, the poor standardization of the diets and feeding protocols usually results in inconsistent and irreproducible data, leading to differences in experimental findings between similar studies

[13].

2.5.1. High-Fat Diet (HFD)/Exposure to High-Fat and Palatable Diets

The obese mouse model, induced by a HFD, is one of the most important tools for understanding the relationship between hyperlipidemic diets and the pathophysiology of obesity development

[68]. There are several strains of mice susceptible to DIO, although there are also animals that appear to be resistant to increasing body weight when exposed to HFDs, termed ‘diet resistant (DR)’

[16][70]. The mouse C57BL/6 strain is highly susceptible in contrast to the mouse strains SWR/J, A/J and CAST/Ei which tend to be resistant to these diets. The C57BL/6J mouse, an inbred strain, is the most commonly used due to the similarities that are observed between them and humans in relation to the development of the metabolic syndrome when fed a HFD, resulting in an obese phenotype. After eating a HFD these animals develop obesity, high adiposity accumulation, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. They are also susceptible to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and endothelium damage, commonly associated with cardiovascular diseases. All the characteristics described above are described in humans with complex metabolic syndrome

[6][7][68][71][72].

In addition to mice, some rat strains can also be used for HFD-induced obesity models, such as outbred Sprague Dawley, Wistar, or Long-Evans rats

[14]. Weight gain induced by diet changes causes defects in the neuronal response to negative feedback signals from circulating adiposity, such as insulin. Insulin resistance involves cellular inflammatory responses caused by excess lipids. This model of diet-induced obesity (DIO with HFD diets) has become one of the most important tools for understanding the interaction of these diets high in saturated fat and the development of this disease

[68]. Outbred Sprague-Dawley rats showed diverse responses, where some animals show DIO while others show DR responses

[16].

2.5.2. High-Carbohydrate Diet (HCD)

A high-carbohydrate diet combined with animal or vegetable fat can mimic the human diet. This diet, in rodents, induces metabolic syndrome. The fat source can vary, and fructose and sucrose are the most common carbohydrates present in these diets, also varying their amounts

[70]. When fed diets high in fat and sucrose, rodents tend to increase their body weight and deposition of abdominal fat, as well as develop hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperleptinemia

[70][73]. In addition, consumption of these diets can also cause fatty liver and increase liver lipogenic enzymes

[74][75]. Fructose ingestion in animals induces an increase in body weight and deposition of abdominal fat, increases plasma levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, free fatty acids and leptin, induces insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and is associated with fatty liver and inflammation

[76]. These animals also show cardiac hypertrophy, ventricular stiffness and dilation, hypertension, cardiac inflammation and fibrosis, decreased cardiac function and endothelial dysfunction together with mild renal damage and increased pancreatic islet mass

[70]. Hypercaloric diets induce hyperglycemia and consequently induce glucose tolerance and increase plasma levels of TAG, TNF-α, and MCP-1/JE, as well as MCP-1/JE levels in organs such as the liver and adipose tissue

[77]. Animals fed with a HCD show, however, a lower body weight gain when compared to animals fed with a HFD

[68].