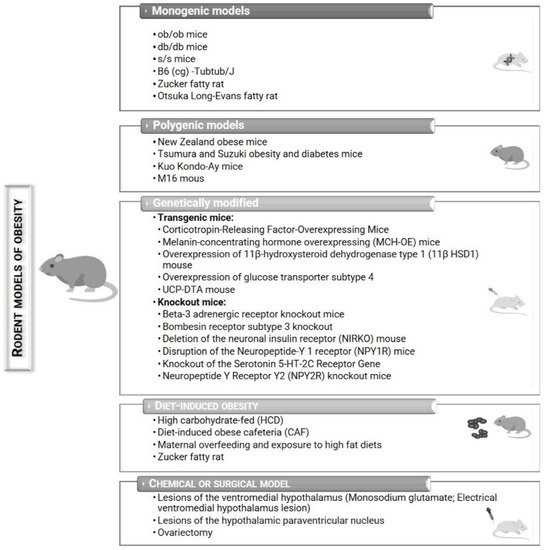

Obesity, classified as an epidemic by the WHO, is a disease that continues to grow worldwide. Obesity results from abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat and usually leads to the development of other associated diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, among others. In vitro and in vivo models have been crucial for studying the underlying mechanisms of obesity, discovering new therapeutic targets, and developing and validating new pharmacological therapies against obesity. Preclinical animal models of obesity comprise a variety of species: invertebrates, fishes, and mammals. However, small rodents are the most widely used due to their cost-effectiveness, physiology, and easy genetic manipulation. The induction of obesity in rats or mice can be achieved by the occurrence of spontaneous single-gene mutations or polygenic mutations, by genetic modifications, by surgical or chemical induction, and by ingestion of hypercaloric diets.

- rodents

- monogenic

- polygenic

- genetically modified

- diet-induced

- chemically induced

- surgically induced

- obesity

- models

1. Introduction

2. Rodent Models of Obesity

| Models | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Monogenic |

|

|

| Polygenic |

|

|

| Genetically modified |

|

|

| Diet-induced |

|

|

| Chemical or surgical |

|

|

2.1. Monogenic Models

2.1.1. ob/ob Mice

2.1.2. db/db Mice

2.1.3. s/s Mice

2.2. Polygenic Models

2.2.1. New Zealand Obese Mice

2.3. Genetically Modified Mice

2.3.1. Transgenic Mice

Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Overexpressing Mice

Melanin-Concentrating Hormone Overexpressing (MCH-OE) Mice

2.3.2. Knockout Mice

Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor Knockout Mice

Bombesin Receptor Subtype 3 Knockout Mice

2.4. Chemical or Surgical Models of Obesity

2.4.1. Lesions of the Ventromedial Hypothalamus

Monosodium Glutamate (MSG)

2.5. Diet-Induced Obesity (DIO)

2.5.1. High-Fat Diet (HFD)/Exposure to High-Fat and Palatable Diets

2.5.2. High-Carbohydrate Diet (HCD)

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/obesities2020012