Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chandra Mohan | -- | 3814 | 2022-04-13 06:34:25 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3814 | 2022-04-14 05:20:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mohan, C.; Abunofal, O. Green Tea Catechins in Fatty Liver Disease. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21682 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Mohan C, Abunofal O. Green Tea Catechins in Fatty Liver Disease. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21682. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Mohan, Chandra, Omar Abunofal. "Green Tea Catechins in Fatty Liver Disease" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21682 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Mohan, C., & Abunofal, O. (2022, April 13). Green Tea Catechins in Fatty Liver Disease. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21682

Mohan, Chandra and Omar Abunofal. "Green Tea Catechins in Fatty Liver Disease." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is a polyphenol green tea catechin with potential health benefits and therapeutic effects in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common liver disorder that adversely affects liver function and lipid metabolism.

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

epigallocatechin-3-gallate

green tea extracts

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a chronic hepatic disorder characterized by excessive lipid accumulation in the liver, which is not secondary to alcohol consumption. NAFLD can progress to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, and eventual liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver failure [1]. Patients in certain risk categories, including obesity, type II diabetes, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and those who consume high-fat diets (HFDs) are particularly prone to NAFLD. Approximately 20–33% of adults in the United States have NAFLD, resulting in an estimated annual economic burden of $103 billion in direct costs [2][3].

Although there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved medications for NAFLD or NASH, some treatment strategies may reduce the manifestations of NAFLD. Diet and lifestyle modifications aid in limiting caloric intake, increasing physical activity, and improving liver histology. Various pharmacologic therapies regulate enzymatic activities in the liver, limit lipid formation, and prevent excessive inflammation and oxidative stress. However, most medications have had limited success or have substantial limitations, such as being unsustainable in long-term administration. Clinical trials of some medications failed to demonstrate high efficacy, whereas other studies evaluated only a small number of participants [4].

Green tea catechins are supplements that were widely studied over the past two decades for NAFLD. Green tea extracts (GTEs) are rich in flavonoids and possess prominent anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and antilipidemic properties [5]. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) is the most commonly studied flavonoid because of its high abundance in green tea. Potential benefits of EGCG have been demonstrated in various in vitro and in vivo studies of animal models, and in various clinical trials of patients with NAFLD. In addition to its substantial benefits in NAFLD, EGCG also has positive effects in cancer, cardiovascular diseases, type II diabetes, and metabolic health, among others [6].

2. Findings from Rodent Studies

A wide range of analyses were performed in studies examining the effects of EGCG in rodent models. These studies explored clinicopathologic effects, lipid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, inflammatory markers, oxidative stress markers, and liver enzymes associated with EGCG treatment. In most studies, EGCG was delivered in the rodent chow. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics and findings of the 30 rodent studies included in this entry.

Table 1. Clinical Efficacy of EGCG Supplementation in Rodent Models.

| Study [Ref] | Model | EGCG Intake | Duration | Clinical/Pathological Outcome | Lipid Metabolism | Carbohydrate Metabolism | Inflammatory Markers | Oxidative Stress Markers | Liver Injury Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raederstorff 2003 [7] | HFD (R) | 0.25–1% (CD) | 4 weeks | ↑ Fecal fat/cholesterol/lipid excretion; ↔ Body weight, liver weight, food intake |

↓ TC, LDL, HDL, TG | ||||

| Fiorini 2005 [8] | I/R (M) | 85 mg/kg (DW/IP) |

5 days | ↓ Body weight, steatosis; ↔ Food intake |

↓ FAS | ↑ GSH; ↔ UCP |

↓ ALT | ||

| Kuzu 2007 [9] | HFD (R) | 1 g/L (DW) | 6 weeks | ↓ Body weight, liver weight, steatosis, inflammation; ↔ Degeneration, necrosis |

↓ TG; ↔ TC |

↓ Insulin, IR | ↓ MDA, CYP2E1; ↑ GSH |

↓ ALT; ↔ ALP, AST |

|

| Bose 2008 [10] | HFD (M) | 3.2 g/kg (CD) | 16 weeks | ↓ Body weight, liver weight, MAT, VAT, EAT, RAT | ↓ TG; ↑ Fecal lipids |

↓ Glucose, insulin, IR | ↓ ALT | ||

| Lee 2008 [11] | HFD (M) | 0.2–0.5% (CD) | 8 weeks | ↓ Body weight, EAT, VAT, RAT; ↔ Liver weight, energy intake |

↓ TC, LDL, PPAR-γ, FAS, LPL; ↑ CPT-I, HSL, ATGL |

↑ UCP-II | ↔ ALT, AST | ||

| Ueno 2009 [12] | NASH (M) | 0.05–0.1% (DW) | 42 weeks | ↓ Steatosis, intralobular fibrosis, ballooning; ↔ Body weight |

↓ TC, TG; ↔ FFA |

↓ Glucose | ↓ pAkt, pIKKß, pNF-κB | ↓ 8-OhdG | ↓ ALT; ↔ AST |

| Chen 2009 [13] | HFD (R) | 1 mg/kg (DW) | 23 weeks | ↓ WAT;↑ Body weight; ↔ Food intake |

↑ PPAR-γ; ↔ TC, LDL, HDL, TG, SREBP-1C, PPAR-α, CPT-II, FAS, ACC |

↓ Glucose | ↑ UCP-II; ↔ ACO, MCD |

||

| Chen 2011 [14] | HFD (M) | 0.32% (CD) | 17 weeks | ↓ Body weight, BAT, steatosis; ↔ Food intake |

↓ TG; ↑ Fecal lipids |

↓ Glucose, insulin, IR | ↓ ALT, HSL | ||

| Sae-tan 2011 [15] | HFD (M) | 0.32% (CD) | 15 weeks | ↓ Body weight, liver weight; ↔ Food intake |

↓ TG | ↓ Glucose, insulin | ↓ ALT | ||

| Sugiura 2012 [16] | HFD (M) | 0.1% (DW) | 4 weeks | ↔ Body weight, liver weight, food intake, IPAT | ↔ TC, TG, FAS, CPT-II | ↔ ACO | |||

| Sumi 2013 [17] | HFD (R) | 0.01–0.1% (DW) | 7 weeks | ↓ Liver fibrosis, steatosis; ↔ Body weight, liver weight | ↓ TG | ↑ TNF-α, IL-6 | ↓ GPx-1, GST-P+, 8-OHdG, d-ROM; ↑ CAT |

↓ ALT | |

| Kochi 2013 [18] | HFD (R) | 0.1% (DW) | 9 weeks | ↓ Steatosis; ↑ Body weight |

↓ MDA, 8-OHdG, GST-P+, d-ROM, CYP2E1; ↑ GPx, CAT |

||||

| Xiao 2013 [19] | HFD (R) | 50 mg/kg (IP) | 8 weeks | ↓ Body weight, food intake, steatosis, fibrosis | ↓ TNF-α, COX-2 | ↑ GPx, CAT; ↔ SOD |

|||

| Krishnan 2014 [20] | HFD (R) | 100 mg/kg (OG) | 30 days | ↓ Steatosis, inflammation | ↓ NF-κB, TNF-α | ||||

| Gan 2015 [21] | HFD (M) | 10–40 mg/kg (IP) | 24 weeks | ↓ Energy intake, body weight, liver weight, steatosis, VAT; ↑ Hepatic cells |

↓ TC, TG, LDL; ↑ HDL |

↓ Glucose, insulin, IR, glucose intolerance | |||

| Ding 2015 [22] | MCDD (M) | 25–100 mg/kg (IP) | 4 weeks | ↓ Body weight, liver weight, food intake | ↓ IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1 | ↓ MDA; ↑ SOD |

↓ AST, ALT | ||

| Santamarina 2015 [23] | HFD (M) | 50 mg/kg (DW) | 16 weeks | ↓ Body weight, WAT, ectopic fat, MAT; ↔ Liver weight, EAT, RAT |

↓ Glucose, insulin, IR | ↔ TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-6R, IL-10Rα | |||

| Mi 2017 [24] | HFD (M) | 2 g/L (DW) | 16 weeks | ↓ Body weight, liver weight, BAT | ↓ TG, TC, LDL; ↑ HDL, PPAR-γ, ACC, SIRT-I, FAS, SREBP-1C, CPT-II, CPT-Iα |

↓ Glucose, insulin, IR; ↑ Glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity |

|||

| Huang 2018 [25] | HFD (M) | 3.2 g/kg (CD) | 33 weeks | ↔ Body weight, liver weight, food intake | ↓ LDL; ↑ HDL, HMGCR, PPARα; ↔ TG, FAS |

↓ Glucose | ↑ CYP7A1, CYP27A1 | ↓ ALT | |

| Yang 2018 [26] | HFD (R) | 160 mg/kg (OG) | 11 weeks | ↓ Body weight, WAT, energy intake | ↓ TC, LDL, HDL, TG, NEFA | ↓ ALT, AST | |||

| Li 2018 [27] | HFD (R) | 25–100 mg/kg (CD) | 4 weeks | ↓ Liver weight | ↓ TC, LDL, TG, FFA, SREBP-II; ↑ HDL, SIRT-I, FOXO-I; ↔ HMGCR |

↓ MDA | ↓ ALT, AST | ||

| Sheng 2018 [28] | HFD (M) | 100 μg/g (CD) | 8 weeks | ↓ Body weight | ↓ TC, TG; ↔ LPL |

↓ ALP, ALT | |||

| Li 2018 [29] | HFD (m) | 50–100 mg/kg (IG) | 20 weeks | ↓ EAT; ↔ Body weight |

↓ LDL, TC, TG, CPT1α; ↑ HDL, ACC, FAS, ATGL |

↓ PPARα, ACO2; ↑ PPARγ, SREBP1 |

↓ UCP2 | ↑ HSL | |

| Ushiroda 2019 [30] | HFD (M) | 0.32% (CD) | 24 weeks | ↓ Body weight; ↔ Food intake |

↓ TG; ↔ LDL, HDL, TC, NEFA |

↓ ALT, AST | |||

| Hou 2020 [31] | HFD (R) | 0.32% (CD) | 16 weeks | ↔ Body weight | ↓ FFA, TG, IR | ↓ IR | ↓ TNF-α, p-NF-κb, TRAF6, IKKβ, p-IKKβ, TLR4 | ||

| Dey 2020 [32] | HFD (M) | 0.3% (CD) | 8 weeks | ↓ Body weight, liver weight, steatosis, ballooning; ↑ Energy intake |

↓ TC, TG; ↔ NEFA |

↓ Glucose, insulin, IR | ↓ TLR4, NF-κb, MCP-1, TNF-α | ↓ MDA | ↓ ALT |

| Ning 2020 [33] | MCDD (M) | 50 mg/kg (IP/OG) | 2 weeks | ↔ Body weight | ↔ LDL, HDL, TC, TG | ↓ Glucose | ↓ ALT; ↔ AST |

||

| Yuan 2020 [34] | HFD (R) | 50 mg/kg (DW) | 92 weeks | ↓ Body weight; ↔ Food intake |

↓ TC, TG, LDL, FFA; ↔ HDL; ↑ CPT-II, FOXO1, SIRT1, FAS, ACC |

↓ Glucose, insulin | ↓ IL-6, TNF-α; ↑ NF-κB |

↓ ROS; ↑ CAT, SOD; ↔ MDA |

↓ ALT, AST |

| Huang 2020 [35] | HFD (M) | 0.4% (CD) | 14 weeks | ↓ Body weight, EAT, PAT, MAT; ↔ Food intake |

↓ TC, LDL | ↓ Glucose | ↓ TNF-α, IL-6, LPS, MMP-3, COX-2, TLR4 | ↓ ALT, AST | |

| Du 2021 [36] | HFD (M) | 25–50 mg/kg (CD) | 16 weeks | ↓ Body weight, liver weight, steatosis | ↓ TG, HDL, TC; ↔ LDL |

↓ AST, ALT |

↑↓ indicates an increase or decrease in the value of the respective variable. ↔ indicates that no change occurred in that respective variable. Green font represents parameters that were increased; red font represents parameters that were decreased; blue font represents parameters that did not change, following EGCG treatment. Abbreviations: 8-OHdG: 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine; ACC: acetyl CoA carboxylase; ACO: acyl-CoA oxidase; AKT: protein kinase B; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ATGL: adipose triglyceride lipase; BAT: brown adipose tissue; CAT: catalase; CD: chow diet; COX: cyclooxygenase; CPT: carnitine palmitoyl transferase; CYP: cytochrome; d-ROM: derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites; DW: drinking water; EAT: epididymal adipose tissue; EGCG: epigallocatechin-3-gallate; ET: endotoxin; FAS: fatty acid synthase; FFA: free fatty acid; FOXO1: fork-head box O1; GLUT4: insulin-regulated glucose transporter; GPx: glutathione peroxidase; GSH: glutathione; GST-P+: glutathione S-transferase–positive; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HFD: high-fat diet; HMGCR: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase; HSL: hormone-sensitive lipase; IG: intragastric; IKK: inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB kinase; IL: interleukin; IP: intraperitoneal; IPAT: intraperitoneal adipose tissue; IR: insulin resistance; I/R: ischemia/reperfusion; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; LPL: lipoprotein lipase; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; M: mouse; MAT: mesenteric adipose tissue; MCD: malonyl CoA decarboxylase; MCDD: methionine-and choline-deficient diet; MCP: monocyte chemoattractant protein; MDA: malondialdehyde; MMP: matrix metalloproteinases; NASH: non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; NEFA: non-esterified fatty acid; NF: nuclear factor; OG: oral gavage; PAT: peritoneal adipose tissue; PPAR: peroxisome proliferator receptor; R: rat; RAT: retroperitoneal adipose tissue; SIRT: sirtuin; SOD: superoxide dismutase; SREBP: sterol regulatory element binding protein; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; TLR: toll-like receptor; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; TRAF: tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor; UCP: uncoupling protein; VAT: visceral adipose tissue; WAT: white adipose tissue.

2.1. Clinicopathologic Effects

Body weight, liver weight, food intake, water intake, energy intake, and steatosis are common clinicopathologic metrics and metabolic risk factors. The majority of the studies reported a significant decrease in body weight after EGCG treatment [8][9][10][11][14][15][19][21][22][23][24][26][28][30][32][34][35][36] (Table 1). A total of nine studies reported a reduction in liver weight [9][10][15][21][22][24][27][32][36]. In 10 of 11 studies, EGCG supplementation was associated with a significant decrease in the mass of various types of adipose tissue [10][11][13][14][21][23][24][26][29][35]. Lee et al. reported that EGCG led to dose-dependent suppression of genes associated with adipogenesis, such as peroxisome proliferator receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) and CCAAT enhancer-binding protein-α (C/EBP-α) [11].

All studies examining the effects of EGCG on steatosis found that EGCG significantly reduced steatosis, ballooning, and inflammation scores (Table 1) [8][9][12][14][17][18][19][20][21][32][36]. Kuzu et al. reported decreases in steatosis and necrosis, associated with reduced α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) levels [9]. Sumi et al. found that improvement of steatosis with EGCG was associated with inhibition of glutathione S-transferase-A placental form (GST-P)-positive foci, preneoplastic lesions associated with NAFLD [17]. Moreover, Gan et al. reported reduced steatosis accompanied by prominent hepatic cell regeneration, following EGCG administration [21].

2.2. Lipid Metabolism

Many studies reported significant decreases in total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (Table 1). Significant decreases in TC were observed in 13 of 18 studies [7][11][12][21][24][26][27][28][29][32][34][35][36]; significant decreases in TG were reported in 18 of 22 studies [7][9][10][12][14][15][17][21][24][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][34][36]; and significant decreases in LDL were reported in 10 of 14 studies [7][11][21][24][25][26][27][29][34][35]. Thus, there is ample evidence indicating that EGCG exerts anti-hyperlipidemic effects.

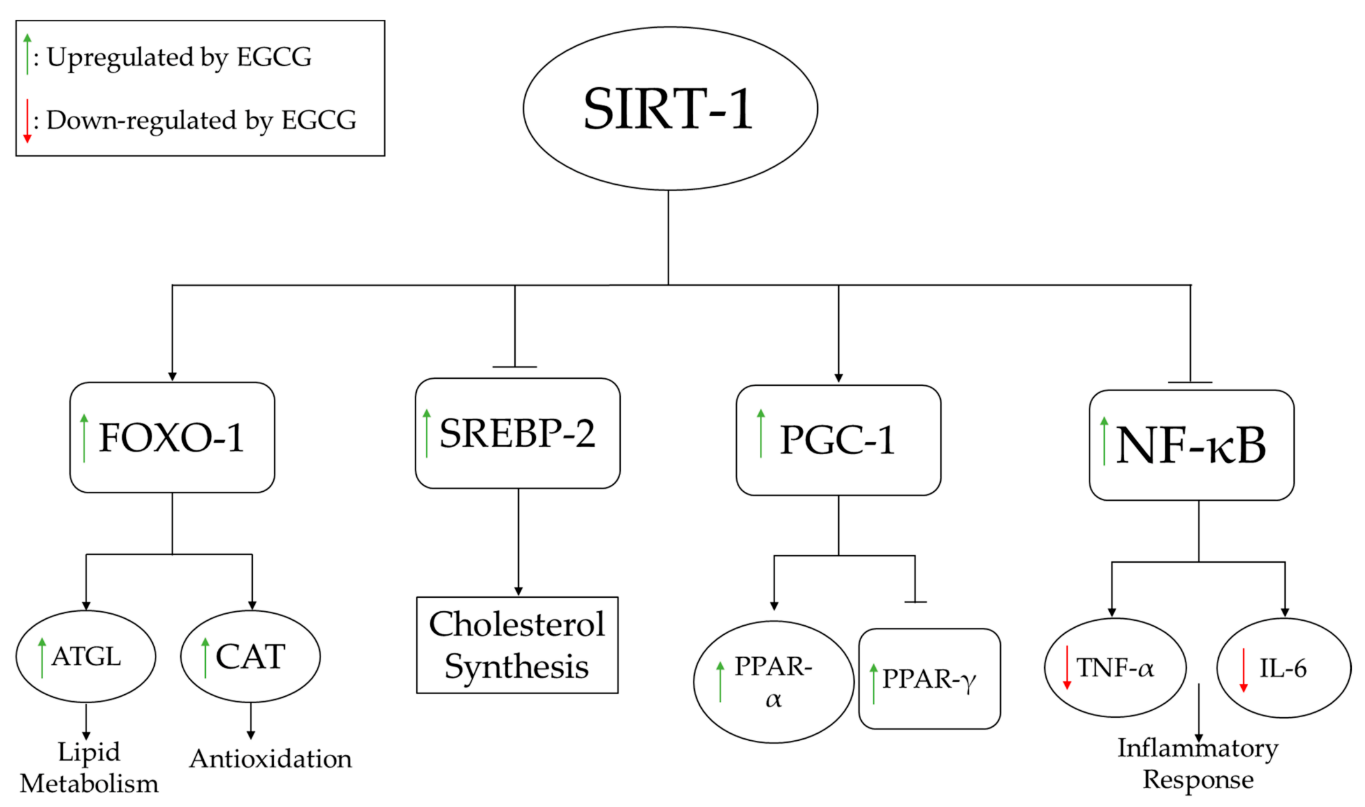

To understand the mechanisms underlying these lipid profile alterations, several pathways directly associated with lipid synthesis were evaluated at the molecular level. For example, Lee et al. examined the dose-dependent effects of EGCG on adipocyte differentiation genes and found that mRNA expression of PPARγ, C/EBP-α, lipoprotein lipase (LPL), and fatty acid synthase (FAS) decreased markedly following EGCG treatment and was highly correlated with a reduction of adipose tissue deposits [11]. Li et al. examined the effects of EGCG on several pathways, including the silent information regulator-1/forkhead box protein O1 (SIRT-1/FOXO1) pathway in conjunction with the regulatory gene, sterol regulatory element binding protein-2 (SREBP-2), which is responsible for regulating cholesterol synthesis [27]. As shown in Figure 1, EGCG supplementation activates SIRT-1, which increases the expression of FOXO1 and decreases the expression of SREBP-2. Increased FOXO1 expression induces lipid metabolism and increases antioxidant (catalase) activity, whereas decreased SREBP-2 expression reduces fatty acid synthesis.

Figure 1. EGCG-induced SIRT-1 modulation of lipid metabolism, antioxidant pathways, inhibition of fatty acid synthesis, and inflammatory response pathways. ATGL increases lipolysis of fats, while increased CAT boosts the antioxidant status. NF-kB regulates several pro-inflammatory pathways, including the production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNFα. Abbreviations: ATGL: adipose triglyceride lipase; CAT: catalase; FOXO-1: fork-head box O1; IL: interleukin; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; PGC: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator; PPAR: peroxisome proliferator receptor; SREBP: sterol regulatory element binding protein; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

2.3. Carbohydrate Metabolism

It is important to consider the effects of EGCG on carbohydrate metabolism, as carbohydrate accumulation has detrimental effects on obesity and liver disease. Interestingly, all studies addressing the impact of EGCG on carbohydrate metabolism reported significant decreases in glucose and insulin levels, as well as insulin resistance (IR), with EGCG treatment [9][10][12][13][14][15][21][22][23][24][25][31][32][33][34][35] (Table 1). Gan et al. showed in their study that intraperitoneal administration of EGCG dose-dependently alleviates hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and IR [21]. The improvement of these parameters can be related to the weight loss reported by these authors.

2.4. Inflammatory Markers

EGCG administration was shown to improve inflammatory profiles associated with liver damage. As shown in Table 1, 11 studies examined changes in inflammatory markers with EGCG administration [12][17][19][20][22][23][29][31][32][34][35], 7 of which reported that EGCG reduced inflammation by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines [19][20][22][31][32][34][35]. Yuan et al. found that EGCG improved inflammation by decreasing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in obese rats, which extended the lifespan of the animals [34]. As shown in Figure 1, activation of SIRT-1 by EGCG leads to inhibition of NF-κB, thereby inhibiting production of TNF-α and IL-6.

2.5. Oxidative Stress Markers

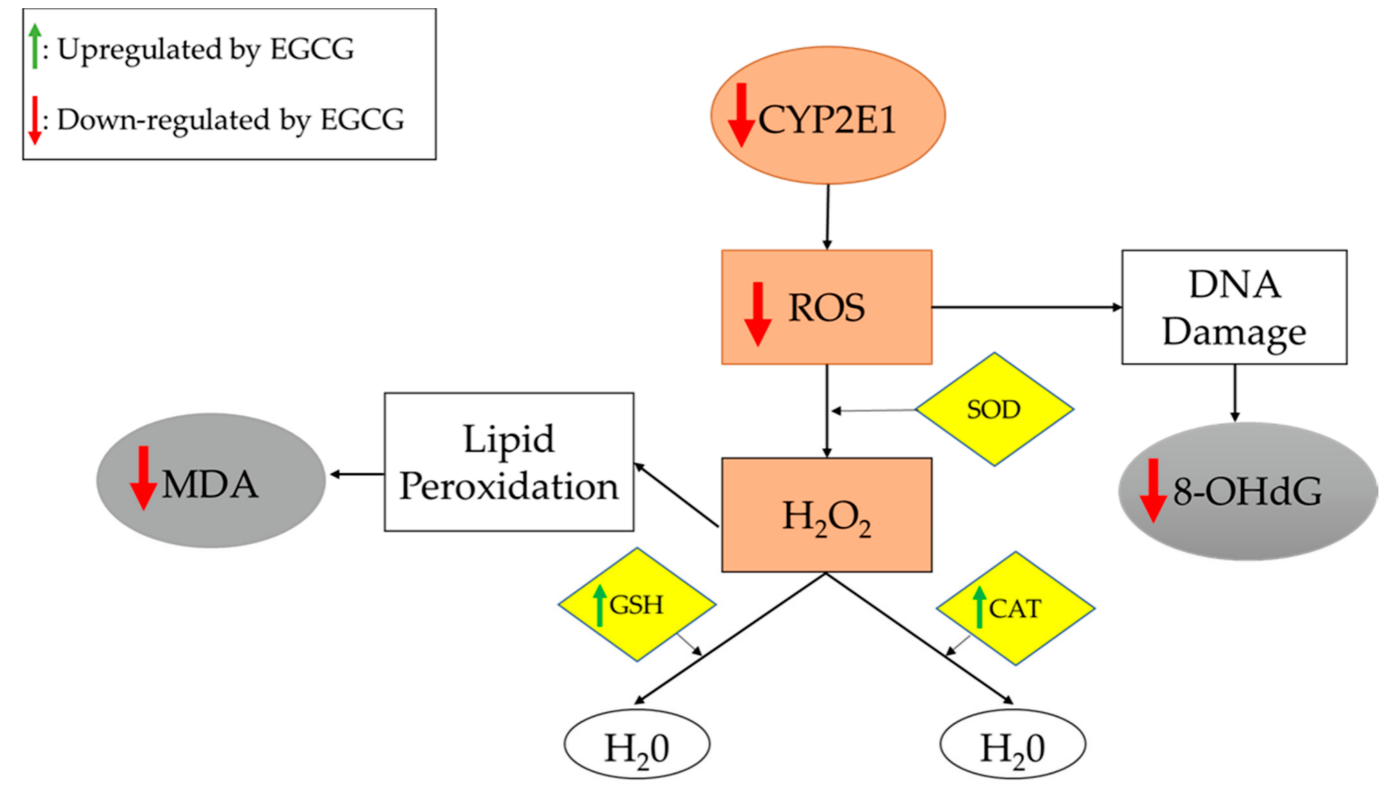

Oxidative stress, a common feature in NAFLD, is facilitated by the accumulation of visceral fat, and contributes to lipid peroxidation that induces systemic oxidative damage [37]. Thus, assaying oxidative stress markers is useful for assessing NAFLD treatment effectiveness. Several important oxidative stress markers were investigated in the studies included in this entry, as listed in Table 1. In 8 of 15 studies, EGCG administration was associated with significant decreases in pro-oxidants, such as CYP2E1 and reactive oxidative species (ROS), as well as oxidative end-products, such as 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and malondialdehyde (MDA) [9][12][17][18][22][27][32][34]. Furthermore, 6 of 10 studies reported significant increases in molecules involved in oxidation/reduction or detoxification reactions, including catalase (CAT), GST, and glutathione (GSH), upon EGCG administration [8][9][17][18][19][20]. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is an enzyme that was evaluated in three studies in this entry [19][22][34]. One study reported no changes in SOD [19], and the other two studies reported a significant increase in SOD [22][34], prompting the need for further studies. In this context, it should be pointed out that increased SOD may help remove superoxide radicals, while reduced SOD may also help by generating less H2O2 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Oxidative stress and antioxidation pathways. Gray boxes represent pro-oxidation end-products. Brown boxes represent pro-oxidation molecules. Yellow boxes represent antioxidation molecules. Reducing the production of H2O2 or increasing its breakdown will reduce the oxidant stress. EGCG appears to act via both mechanisms. The end result is reduced oxidative damage, as is evidenced by the reduced levels of MDA and 8-OHdG. Abbreviations: 8-OHdG: 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine; CAT: catalase; CYP2E1: cytochrome-2E1; GSH: glutathione; MDA: malondialdehyde; ROS: reactive oxidative species; SOD: superoxide dismutase.

Kuzu et al. examined the effects of EGCG on oxidative stress associated with the CYP2E1 enzyme. These authors concluded that EGCG potentially suppresses CYP2E1-associated oxidative stress, as it decreases lipid peroxidation and increases GSH levels [9]. As shown in Figure 2, EGCG treatment reduces the expression of CYP2E1, leading to decreased synthesis of ROS (which damage DNA) and increased expression of antioxidants, which alleviate oxidative stress.

2.6. Biochemical Markers of Liver Damage

EGCG treatment also improves liver damage biomarkers [8][9][10][12][14][15][17][22][25][26][27][28][30][32][33][34][35][36]. As shown in Table 1, EGCG decreases levels of enzymes associated with liver damage, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Reductions in levels of these enzymes were associated with decreased steatosis.

3. Findings from Human Studies

As summarized in Table 2, 21 studies evaluating catechins, green tea, and EGCG or GTE in humans with NAFLD also evaluated clinicopathologic findings, lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, inflammation, oxidative stress, and liver damage. The majority of these studies conducted their clinical trials over a 12-week period, designed as randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trials (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical Efficacy of Green Tea in Human Studies.

| Study (Ref) | Study Design | Duration (Number of Participants) | Green Tea Component Daily Intake | Clinical/Pathological Outcome | Lipid Metabolism | Carbohydrate Metabolism | Inflammatory Markers | Oxidative Stress Markers | Liver Injury Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chantre 2002 [38] | Open study | 12 weeks (70) | 375 mg catechin | ↓ Body weight, WC | ↔TC | ||||

| Kovacs 2003 [39] | (R/P/PC) | 13 weeks (104) | 323 mg EGCG | ↔ Body weight, BMI, REE, RQ | ↔ TG, NEFA | ↔ Glucose, insulin | |||

| Nagao 2004 [40] | (DB) | 12 weeks (38) | 690 mg catechin | ↓ Body weight, BMI, WC, HC | ↓ LDL; ↑ FFA; ↔ HDL, TG |

↑ Glucose, insulin | ↓ MDA | ||

| Nagao 2006 [41] | (R/DB) | 12 weeks (240) | 583 mg catechin | ↓ Body weight, BMI, WC, HC; ↔ Energy intake |

↓ LDL; ↔ HDL, TC, TG, FFA |

↔ Glucose | ↔ ALP | ||

| Auvichayapat 2007 [42] | (R) | 12 weeks (60) | 750 mg green tea | ↓ Body weight, BMI; ↑ REE; ↔ Food intake, physical activity, RQ |

|||||

| Hill 2007 [43] | (R/PC) | 12 weeks (38) | 300 mg EGCG | ↓ Total body fat, WC; ↔ Body weight, energy intake, EE, BMI, HC |

↔ Glucose, insulin | ||||

| Hsu 2008 [44] | (R/DB/PC) | 12 weeks (78) | 1200 mg GTE | ↓ WC, HC; ↔ Body weight, BMI |

↓ LDL, TG; ↑ HDL; ↔ TC |

↔ Insulin, IR | ↔ AST | ||

| Matsuyama 2008 [45] | (R/DB) | 36 weeks (40) | 75–576 mg catechins | ↔ Body weight, BMI, HC | ↓ TG, FFA | ↓ Glucose | ↑ CRP | ↓ AST, ALT | |

| Maki 2008 [46] | (R/DB/C) | 12 weeks (107) | 625 mg EGCG | ↓ Body weight; ↔ Physical activity, energy intake, WC |

↓ TG, FFA; ↔ LDL, HDL |

↔ Glucose, insulin | ↔ CRP | ↔ MDA | |

| Brown 2009 [47] | (R/DB/PC/P) | 8 weeks (88) | 800 mg EGCG | ↔ BMI, WC | ↔ TC, HDL, LDL, TG | ↔ Insulin, IR | |||

| Pierro 2009 [48] | (R) | 90 days (100) | 300 mg GTE | ↓ Body weight, BMI | ↓ TG, LDL, TC; ↑ HDL | ↓ Glucose, insulin | |||

| Basu 2010 [49] | (R/C) | 8 weeks (35) | 440 mg EGCG | ↔ WC | ↔ TG, HDL | ↔ Glucose | ↔ IL-6, IL-1β, sVCAM-1, CRP | ↔ AST, ALT | |

| Basu 2010 [50] | (R/C/SB) | 8 weeks (35) | 900 mg EGCG in capsule | ↔ Body weight, BMI, WC | ↓ TC, LDL; ↔ TG |

↔ Glucose, IR | ↓ MDA | ||

| Thielecke 2010 [51] | (R/DB/PC/X) | 3 days (12) | 300–600 mg EGCG in capsule | ↔ EE, RQ | ↔ NEFA | ↔ Glucose, insulin | |||

| Brown 2011 [52] | (R/PC/X) | 6 weeks (70) | 800 mg catechins | ↑ Energy intake; ↔ Body weight |

↓ LDL; ↔ HDL, TG |

↔ Glucose, insulin | |||

| Bogdanski 2011 [53] | (DB/PC) | 3 months (56) | 379 mg GTE | ↔ BMI, WC | ↓ TC, LDL, TG; ↑ HDL |

↓ Glucose, insulin, IR | ↓ CRP, TNF-α | ↑ TAS | |

| Suliburska 2012 [54] | (R/DB/PC/C) | 3 months (46) | 379 mg GTE | ↓ BMI, WC | ↓TC, LDL, TG; ↔ HDL |

↔ Glucose | ↑ TAS | ||

| Mielgo-Ayuso 2013 [55] | (R/DB/PC) | 12 weeks (88) | 300 mg EGCG | ↓ Body weight, BMI, WC | ↓ TC, LDL, HDL; ↔ TG |

↓ Insulin, IR | ↓ AST; ↔ ALT |

||

| Pezeshki 2016 [56] | (R/DB/PC) | 90 days (80) | 500 mg GTE | ↓ Body weight, BMI | ↓ AST, ALT, ALP | ||||

| Hussain 2017 [57] | (R/PC) | 91 days (80) | 500 mg GTE | ↓ Body weight, BMI | ↓ TC, LDL, TG; ↑ HDL |

↓ IR | ↓ CRP | ↓ AST, ALT | |

| Roberts 2021 [58] | (R/DB/PC) | 8 weeks (27) | 580 mg GTE | ↔ Body weight, BMI, EE, WC | ↔ TC, TG, LDL, HDL, FFA | ↔ALT, AST, ALP |

↑↓ indicates an increase or decrease in the value of the respective variable. ↔ indicates that no change occurred in that respective variable. Green font represents the parameters that were increased; red font represents the parameters that were decreased; blue font represents parameters that did not change, following EGCG treatment. Abbreviations: ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BMI: body mass index; C: controlled; CRP: C-reactive protein; DB: double-blind; EE: energy expenditure; EGCG: epigallocatechin-3-gallate; FFA: free fatty acid; GTE: green tea extract; HC: hip circumference; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; IL: interleukin; IR: insulin resistance; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; MDA: malondialdehyde; NEFA: non-esterified fatty acid; P: parallel; PC: placebo controlled; R: randomized; REE: resting energy expenditure; RQ: respiratory quotient; sVCAM: circulating vascular adhesion molecule; TAS: total antioxidant status; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; WC: waist circumference; X: cross-over trial.

3.1. Clinicopathologic Effects

Administration of EGCG, GTE, and catechins was associated with a significant decrease in body weight in 9 of 15 studies [38][40][41][42][46][48][55][56][57] and a significant decrease in body mass index (BMI) in 7 of these 9 studies [40][41][42][48][55][56][57] (Table 2). Maki et al. examined the effects of green tea catechins on the body composition with obese adults and noted direct effects, similar to the findings in rodent studies [46].

Waist circumference (WC) was frequently evaluated as a surrogate for changes in body weight and fat loss. Five studies reported decreases in WC with catechins, EGCG, and GTE, concurrent with decreases in body weight [38][40][41][54][55]. Moreover, it is important to consider other possible mechanisms that may explain the decreases in body weight. For example, Chantre et al. found that GTE supplementation can inhibit gastric and pancreatic lipases, stimulate thermogenesis, increase energy expenditure (EE), and lower body weight; these changes can have substantial health benefits in obese patients [38]. In general, most studies did not find a change in energy intake or expenditure following treatment with EGCG/GTE (Table 2).

3.2. Lipid Metabolism

Similar to the rodent studies, the human studies focused on LDL, TG, TC, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) to evaluate the lipid metabolism effects of GTE (Table 2). Significant decreases in LDL were reported in 10 of 12 studies [40][41][44][48][50][52][53][54][55][57], and significant decreases in TC were reported in 6 of 12 studies [48][50][52][53][54][57]. For HDL, 4 of 12 studies reported a significant increase [44][48][53][57], but 7 of 12 studies reported no change [40][41][46][47][48][50][52][53][54]. Brown et al. reported no changes in LDL, HDL, TG, or TC in obese males who received 800 mg/day of oral EGCG [47]. When considering the results of other studies, these authors attributed the lack of improvement to the relatively low dosage of EGCG. They also noted that the peak EGCG plasma concentration was approximately 1 μM, suggesting low oral bioavailability. In general, adequate EGCG/GTE dosages appear to exert salubrious effects on lipid profiles, in resonance with findings from murine studies.

3.3. Carbohydrate Metabolism

Human studies focused on investigating changes in glucose, insulin, and IR to evaluate the effectiveness of GTE in obese patients (Table 2). There were no significant changes in glucose levels in 8 of 12 studies [39][41][43][46][49][50][51][52], insulin levels in 7 of 11 studies [39][43][44][46][47][51][52], and IR in 3 of 6 studies [44][47][50]. Thus, these parameters were not significantly altered by tea catechins in most human studies, although they were significantly reduced in the rodent studies. Of note, the study duration may be important when considering alterations in metabolic syndrome markers. In reviewing the studies in Table 2, it appears that short-term studies reported no change in glucose and insulin, where treatment was administered for less than 6 weeks [51][52]. On the other hand, longer study durations were associated with changes in glucose, insulin, and IR [45][48][53][55]. Taken together, treatment with GTE should preferably be continued for at least 12 weeks, to observe effects on carbohydrate metabolites.

3.4. Inflammatory Markers

As can be seen from Table 2, only five studies assayed inflammatory markers, with no conclusive trends [45][46][49][53][57]. Others reported that catechins have anti-inflammatory properties that suppress leukocyte adhesion to endothelium and inhibit transcription factors for cytokines and adhesion molecules, in other disease contexts. In contrast to rodent studies, few studies have examined the effects of EGCG on inflammatory markers in NAFLD, highlighting the need for more research examining inflammatory profiles in patients with NAFLD.

3.5. Oxidative Stress Markers

An insufficient number of studies evaluated the effects of EGCG or GTE on oxidative stress markers. MDA and total antioxidant status (TAS) were the only oxidative stress markers assayed. MDA is the most frequently used biomarker of oxidative stress in various diseases [59]. TAS has an inverse relationship with other oxidative stress markers, such as MDA, as it represents antioxidative capacity [60]. Two of three studies reported significant decreases in MDA [40][50], and both studies investigating the effects of GTE on TAS reported significant increases [53][54]. Basu et al. reported a significant decrease in MDA, confirming the antioxidant properties of GTE, and Bogandaski et al. reported a significant increase in TAS after 3-month supplementation with GTE, indicating that GTE improved oxidative stress [50][53].

The antioxidative properties of green tea catechins are best appreciated by understanding the structural properties of EGCG. These properties have been attributed to the presence of dihydroxyl or trihydroxyl groups on the B-ring and meta-5,7-dihydroxyl groups on the A-ring. The polyphenolic structure of green tea catechins allows delocalization of electrons, which promotes the elimination of reactive oxygen and nitric radicals [54].

Although limited studies have examined the effects of EGCG or GTE in humans, the available data suggest that EGCG or GTE supplementation is a promising strategy for alleviating oxidative stress. The results of human studies are consistent with those of rodent studies, which clearly demonstrates the antioxidant effects of EGCG. Nevertheless, more research is necessary to confirm the efficacy of these supplements in reducing oxidative stress in humans.

3.6. Liver Enzymes

Similar to rodent studies, serum AST and ALT were common metrics used for assessing liver damage in human studies, and both markers were decreased with EGCG and GTE treatment (Table 2). Following EGCG or GTE administration, significant decreases in AST were reported in four of six studies [45][55][57], and significant decreases in ALT were reported in three of five studies [45][56][57]. Pezeshki et al. reported significant decreases in AST and ALT following 12-week treatment with 500 mg/day of GTE [56]. This result was confirmed by Hussain et al., who found similar results using the same GTE dosage and treatment duration [57].

References

- Smith, B.W.; Adams, L.A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2011, 48, 97–113.

- Kneeman, J.M.; Misdraji, J.; Corey, K.E. Secondary causes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2011, 5, 199–207.

- Younossi, Z.M.; Blissett, D.; Blissett, R.; Henry, L.; Stepanova, M.; Younossi, Y.; Racila, A.; Hunt, S.; Beckerman, R. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology 2016, 64, 1577–1586.

- Beaton, M.D. Current treatment options for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 353–357.

- Sakata, R.; Nakamura, T.; Torimura, T.; Ueno, T.; Sata, M. Green tea with high-density catechins improves liver function and fat infiltration in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients: A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 989–994.

- Wolfram, S. Effects of Green Tea and EGCG on Cardiovascular and Metabolic Health. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 373S–388S.

- Raederstorff, D.G.; Schlachter, M.F.; Elste, V.; Weber, P. Effect of EGCG on lipid absorption and plasma lipid levels in rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2003, 14, 326–332.

- Fiorini, R.N.; Donovan, J.L.; Rodwell, D.; Evans, Z.; Cheng, G.; May, H.D.; Milliken, C.E.; Markowitz, J.S.; Campbell, C.; Haines, J.K.; et al. Short-term administration of (-)-epigallocatechin gallate reduces hepatic steatosis and protects against warm hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in steatotic mice. Liver Transplant. 2005, 11, 298–308.

- Kuzu, N.; Bahcecioglu, I.H.; Dagli, A.F.; Ozercan, I.H.; Ustündag, B.; Sahin, K. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis induced by high fat diet. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, e465–e470.

- Bose, M.; Lambert, J.D.; Ju, J.; Reuhl, K.R.; Shapses, S.; Yang, C.S. The Major Green Tea Polyphenol, (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate, Inhibits Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Fatty Liver Disease in High-Fat–Fed Mice. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 1677–1683.

- Lee, M.-S.; Kim, C.-T.; Kim, Y. Green Tea (–)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Reduces Body Weight with Regulation of Multiple Genes Expression in Adipose Tissue of Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 54, 151–157.

- Ueno, T.; Torimura, T.; Nakamura, T.; Sivakumar, R.; Nakayama, H.; Otabe, S.; Yuan, X.; Yamada, K.; Hashimoto, O.; Inoue, K.; et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate improves nonalcoholic steatohepatitis model mice expressing nuclear sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c in adipose tissue. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2009, 24, 17–22.

- Chen, N.; Bezzina, R.; Hinch, E.; Lewandowski, P.A.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Mathai, M.L.; Jois, M.; Sinclair, A.J.; Begg, D.P.; Wark, J.D.; et al. Green tea, black tea, and epigallocatechin modify body composition, improve glucose tolerance, and differentially alter metabolic gene expression in rats fed a high-fat diet. Nutr. Res. 2009, 29, 784–793.

- Chen, Y.-K.; Cheung, C.; Reuhl, K.R.; Liu, A.B.; Lee, M.-J.; Lu, Y.-P.; Yang, C.S. Effects of Green Tea Polyphenol (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate on Newly Developed High-Fat/Western-Style Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 11862–11871.

- Sae-Tan, S.; Grove, K.A.; Kennett, M.J.; Lambert, J.D. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate increases the expression of genes related to fat oxidation in the skeletal muscle of high fat-fed mice. Food Funct. 2011, 2, 111–116.

- Sugiura, C.; Nishimatsu, S.; Moriyama, T.; Ozasa, S.; Kawada, T.; Sayama, K. Catechins and Caffeine Inhibit Fat Accumulation in Mice through the Improvement of Hepatic Lipid Metabolism. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 520510.

- Sumi, T.; Shirakami, Y.; Shimizu, M.; Kochi, T.; Ohno, T.; Kubota, M.; Shiraki, M.; Tsurumi, H.; Tanaka, T.; Moriwaki, H. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate suppresses hepatic preneoplastic lesions developed in a novel rat model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 690.

- Kochi, T.; Shimizu, M.; Terakura, D.; Baba, A.; Ohno, T.; Kubota, M.; Shirakami, Y.; Tsurumi, H.; Tanaka, T.; Moriwaki, H. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and preneoplastic lesions develop in the liver of obese and hypertensive rats: Suppressing effects of EGCG on the development of liver lesions. Cancer Lett. 2014, 342, 60–69.

- Xiao, J.; Ho, C.T.; Liong, E.C.; Nanji, A.A.; Leung, T.M.; Lau, T.Y.H.; Fung, M.L.; Tipoe, G.L. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates fibrosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease rat model through TGF/SMAD, PI3 K/Akt/FoxO1, and NF-kappa B pathways. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 187–199.

- Krishnan, T.R.; Velusamy, P.; Srinivasan, A.; Ganesan, T.; Mangaiah, S.; Narasimhan, K.; Chakrapani, L.N.; Thanka, J.; Walter, C.E.J.; Durairajan, S.; et al. EGCG mediated downregulation of NF-AT and macrophage infiltration in experimental hepatic steatosis. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 57, 96–103.

- Gan, L.; Meng, Z.-J.; Xiong, R.-B.; Guo, J.-Q.; Lu, X.-C.; Zheng, Z.-W.; Deng, Y.-P.; Luo, B.-D.; Zou, F.; Li, H. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate ameliorates insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 597–605.

- Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Qian, K. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuated non-alcoholic steatohepatitis induced by methionine- and choline-deficient diet. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 761, 405–412.

- Santamarina, A.B.; Carvalho-Silva, M.; Gomes, L.M.; Okuda, M.H.; Santana, A.A.; Streck, E.L.; Seelaender, M.; Nascimento, C.M.O.D.; Ribeiro, E.B.; Lira, F.S.; et al. Decaffeinated green tea extract rich in epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents fatty liver disease by increased activities of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes in diet-induced obesity mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 1348–1356.

- Mi, Y.; Qi, G.; Fan, R.; Ji, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X. EGCG ameliorates diet-induced metabolic syndrome associating with the circadian clock. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1575–1589.

- Huang, J.; Feng, S.; Liu, A.; Dai, Z.; Wang, H.; Reuhl, K.; Lu, W.; Yang, C.S. Green Tea Polyphenol EGCG Alleviates Metabolic Abnormality and Fatty Liver by Decreasing Bile Acid and Lipid Absorption in Mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1700696.

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, M.-Z.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Wen, B.-B.; An, H.-M.; Ou, X.-C.; Xiong, Y.-F.; Lin, H.-Y.; Liu, Z.-H.; Huang, J.-A. Coadministration of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) and caffeine in low dose ameliorates obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in obese rats. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 1019–1026.

- Li, Y.; Wu, S. Epigallocatechin gallate suppresses hepatic cholesterol synthesis by targeting SREBP-2 through SIRT1/FOXO1 signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 448, 175–185.

- Sheng, L.; Jena, P.K.; Liu, H.; Hu, Y.; Nagar, N.; Bronner, D.N.; Settles, M.L.; Baümler, A.J.; Wan, Y.Y. Obesity treatment by epigallocatechin-3-gallate−regulated bile acid signaling and its enriched Akkermansia muciniphila. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 6371–6384.

- Li, F.; Gao, C.; Yan, P.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Sheng, J.; Li, F.; et al. EGCG Reduces Obesity and White Adipose Tissue Gain Partly Through AMPK Activation in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1366.

- Ushiroda, C.; Naito, Y.; Takagi, T.; Uchiyama, K.; Mizushima, K.; Higashimura, Y.; Yasukawa, Z.; Okubo, T.; Inoue, R.; Honda, A.; et al. Green tea polyphenol (epigallocatechin-3-gallate) improves gut dysbiosis and serum bile acids dysregulation in high-fat diet-fed mice. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2019, 65, 34–46.

- Hou, H.; Yang, W.; Bao, S.; Cao, Y. Epigallocatechin Gallate Suppresses Inflammatory Responses by Inhibiting Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling and Alleviates Insulin Resistance in the Livers of High-fat-diet Rats. J. Oleo Sci. 2020, 69, 479–486.

- Dey, P.; Olmstead, B.D.; Sasaki, G.Y.; Vodovotz, Y.; Yu, Z.; Bruno, R.S. Epigallocatechin gallate but not catechin prevents nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice similar to green tea extract while differentially affecting the gut microbiota. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 84, 108455.

- Ning, K.; Lu, K.; Chen, Q.; Guo, Z.; Du, X.; Riaz, F.; Feng, L.; Fu, Y.; Yin, C.; Zhang, F.; et al. Epigallocatechin Gallate Protects Mice against Methionine–Choline-Deficient-Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis by Improving Gut Microbiota to Attenuate Hepatic Injury and Regulate Metabolism. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20800–20809.

- Yuan, H.; Li, Y.; Ling, F.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Niu, Y. The phytochemical epigallocatechin gallate prolongs the lifespan by improving lipid metabolism, reducing inflammation and oxidative stress in high-fat diet-fed obese rats. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13199.

- Huang, J.; Li, W.; Liao, W.; Hao, Q.; Tang, D.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Ge, G. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate alleviates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and ameliorates intestinal immunity in mice fed a high-fat diet. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9924–9935.

- Du, Y.; Paglicawan, L.; Soomro, S.; Abunofal, O.; Baig, S.; Vanarsa, K.; Hicks, J.; Mohan, C. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Dampens Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver by Modulating Liver Function, Lipid Profile and Macrophage Polarization. Nutrients 2021, 13, 599.

- Marseglia, L.; Manti, S.; D’Angelo, G.; Nicotera, A.G.; Parisi, E.; Di Rosa, G.; Gitto, E.; Arrigo, T. Oxidative Stress in Obesity: A Critical Component in Human Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 16, 378–400.

- Chantre, P.; Lairon, D. Recent findings of green tea extract AR25 (Exolise) and its activity for the treatment of obesity. Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 3–8.

- Kovacs, E.M.R.; Lejeune, M.P.G.M.; Nijs, I.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S. Effects of green tea on weight maintenance after body-weight loss. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 91, 431–437.

- Nagao, T.; Komine, Y.; Soga, S.; Meguro, S.; Hase, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Tokimitsu, I. Ingestion of a tea rich in catechins leads to a reduction in body fat and malondialdehyde-modified LDL in men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 122–129.

- Nagao, T.; Hase, T.; Tokimitsu, I. A Green Tea Extract High in Catechins Reduces Body Fat and Cardiovascular Risks in Humans. Obesity 2007, 15, 1473–1483.

- Auvichayapat, P.; Prapochanung, M.; Tunkamnerdthai, O.; Sripanidkulchai, B.-O.; Auvichayapat, N.; Thinkhamrop, B.; Kunhasura, S.; Wongpratoom, S.; Sinawat, S.; Hongprapas, P. Effectiveness of green tea on weight reduction in obese Thais: A randomized, controlled trial. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 93, 486–491.

- Hill, A.; Coates, A.; Buckley, J.; Ross, R.; Thielecke, F.; Howe, P.R. Can EGCG Reduce Abdominal Fat in Obese Subjects? J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 396S–402S.

- Hsu, C.-H.; Tsai, T.-H.; Kao, Y.-H.; Hwang, K.-C.; Tseng, T.-Y.; Chou, P. Effect of green tea extract on obese women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 363–370.

- Matsuyama, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Kamimaki, I.; Nagao, T.; Tokimitsu, I. Catechin Safely Improved Higher Levels of Fatness, Blood Pressure, and Cholesterol in Children. Obesity 2008, 16, 1338–1348.

- Maki, K.C.; Reeves, M.S.; Farmer, M.; Yasunaga, K.; Matsuo, N.; Katsuragi, Y.; Komikado, M.; Tokimitsu, I.; Wilder, D.; Jones, F.; et al. Green Tea Catechin Consumption Enhances Exercise-Induced Abdominal Fat Loss in Overweight and Obese Adults. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 264–270.

- Brown, A.L.; Lane, J.; Coverly, J.; Stocks, J.; Jackson, S.; Stephen, A.; Bluck, L.; Coward, A.; Hendrickx, H. Effects of dietary supplementation with the green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate on insulin resistance and associated metabolic risk factors: Randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 886–894.

- Di Pierro, F.; Menghi, A.B.; Barreca, A.; Lucarelli, M.; Calandrelli, A. Greenselect Phytosome as an adjunct to a low-calorie diet for treatment of obesity: A clinical trial. Altern. Med. Rev. 2009, 14, 154–160.

- Basu, A.; Du, M.; Sanchez, K.; Leyva, M.J.; Betts, N.M.; Blevins, S.; Wu, M.; Aston, C.E.; Lyons, T.J. Green tea minimally affects biomarkers of inflammation in obese subjects with metabolic syndrome. Nutrition 2011, 27, 206–213.

- Basu, A.; Sanchez, K.; Leyva, M.J.; Wu, M.; Betts, N.M.; E Aston, C.; Lyons, T.J. Green Tea Supplementation Affects Body Weight, Lipids, and Lipid Peroxidation in Obese Subjects with Metabolic Syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2010, 29, 31–40.

- Thielecke, F.; Rahn, G.; Böhnke, J.; Adams, F.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Jordan, J.; Boschmann, M. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and postprandial fat oxidation in overweight/obese male volunteers: A pilot study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 704–713.

- Brown, A.L.; Lane, J.; Holyoak, C.; Nicol, B.; Mayes, A.E.; Dadd, T. Health effects of green tea catechins in overweight and obese men: A randomised controlled cross-over trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1880–1889.

- Bogdanski, P.; Suliburska, J.; Szulinska, M.; Stepien, M.; Pupek-Musialik, D.; Jabłecka, A. Green tea extract reduces blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, and oxidative stress and improves parameters associated with insulin resistance in obese, hypertensive patients. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 421–427.

- Suliburska, J.; Bogdanski, P.; Szulinska, M.; Stepien, M.; Pupek-Musialik, D.; Jabłecka, A. Effects of Green Tea Supplementation on Elements, Total Antioxidants, Lipids, and Glucose Values in the Serum of Obese Patients. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 149, 315–322.

- Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Barrenechea, M.L.; Alcorta, P.; Larrarte, E.; Margareto, J.; Labayen, I. Effects of dietary supplementation with epigallocatechin-3-gallate on weight loss, energy homeostasis, cardiometabolic risk factors and liver function in obese women: Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1263–1271.

- Askari, G.; Pezeshki, A.; Safi, S.; Feizi, A.; Karami, F. The effect of green tea extract supplementation on liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 7, 28.

- Hussain, M.; Rehman, H.U.; Akhtar, L. Therapeutic benefits of green tea extract on various parameters in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2017, 33, 931–936.

- Roberts, J.; Willmott, A.; Beasley, L.; Boal, M.; Davies, R.; Martin, L.; Chichger, H.; Gautam, L.; Del Coso, J. The Impact of Decaffeinated Green Tea Extract on Fat Oxidation, Body Composition and Cardio-Metabolic Health in Overweight, Recreationally Active Individuals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 764.

- Khoubnasabjafari, M.; Ansarin, K.; Jouyban, A. Reliability of malondialdehyde as a biomarker of oxidative stress in psychological disorders. BioImpacts 2015, 5, 123–127.

- Wu, R.; Feng, J.; Yang, Y.; Dai, C.; Lu, A.; Li, J.; Liao, Y.; Xiang, M.; Huang, Q.; Wang, N.; et al. Significance of Serum Total Oxidant/Antioxidant Status in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170003.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No