Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tsimur Hasanau | -- | 3227 | 2022-04-11 23:43:27 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 3227 | 2022-04-12 03:56:45 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Hasanau, T.; Pisarev, E.; Kisil, O.; , .; Le Calvez-Kelm, F.; Zvereva, M. TERT Promoter Mutations in Gliomas. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21600 (accessed on 07 March 2026).

Hasanau T, Pisarev E, Kisil O, , Le Calvez-Kelm F, Zvereva M. TERT Promoter Mutations in Gliomas. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21600. Accessed March 07, 2026.

Hasanau, Tsimur, Eduard Pisarev, Olga Kisil, , Florence Le Calvez-Kelm, Maria Zvereva. "TERT Promoter Mutations in Gliomas" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21600 (accessed March 07, 2026).

Hasanau, T., Pisarev, E., Kisil, O., , ., Le Calvez-Kelm, F., & Zvereva, M. (2022, April 11). TERT Promoter Mutations in Gliomas. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21600

Hasanau, Tsimur, et al. "TERT Promoter Mutations in Gliomas." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Telomere length maintenance systems perform an essential function in preserving genome stability. Abnormalities in the functioning of these systems, such as telomerase reactivation, usually play a key role in the course of oncogenesis.TERTp mutations are not found in ordinary human cells, but are often associated with malignant tumor progression and increased cell proliferation in CNS tumor diseases, especially in gliomas. The availability of molecular evaluation of the TERTp mutational status of CNS tumor lesions contributes to more accurate and reliable diagnosis and timely decisions regarding patient follow-up with selection of the most appropriate and applicable treatment protocols.

telomerase reverse transcriptase

telomerase activation

TERT

TERT promoter region

TERTp mutations

glioma

molecular biomarkers

1. Introduction

One of the mechanisms of telomerase reactivation in oncogenesis involves activation of the transcription of the main catalytic component of telomerase due to the occurrence of somatic mutations in the promoter region of the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene [1]. These genomic changes have been reported in a wide range of tumor genomes [2], including in tumors of the central nervous system (CNS), where they have been observed at the highest frequency. The regulation of telomerase expression in gliomas has been shown to depend on the mutational status of the TERT promoter (TERTp) [3]. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) CNS classification first applied molecular markers to classify gliomas, and the recent revised 2021 version reinforced the utility of these markers for more accurate CNS grading systems. Numerous molecular changes of clinicopathological significance are included in the WHO CNS5. In the WHO CNS5 classification system, the mutational status of the telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter is one of the key genetic markers of gliomas [4][5][6].

Cancer-specific TERT expression and mediated telomerase activation have always generated great enthusiasm for the potential clinical applications of TERT/telomerase-based assays in cancer. However, the unstable nature of TERT mRNA and telomerase RNA makes it challenging to reliably analyze direct TERT expression or telomerase activity for cancer diagnosis or monitoring. Nevertheless, numerous clinical research has positively evaluated telomerase activation, especially TERT-related changes, as prognostic factors for cancer patients [6]. However, the recent discovery of widespread TERTp mutations in various tumors provides new opportunities for simple and lost-cost biomarkers in detecting patients with TERT-mutated tumors.

2. Classification of CNS Tumors

There are three main types of glial cells: astrocytes, oligodendrogliocytes, and ependymocytes. According to the type of cells from which a glioma of the brain originates, neurology distinguishes astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and ependymoma; there are also mixed gliomas of the brain, such as oligoastrocytomas [7]. According to the WHO classification, there are four grades (classes) of malignancy of gliomas in the brain [4]. Grade I gliomas, which are often considered benign, are usually curable by complete surgical resection and rarely, if ever, progress to higher-grade lesions. In contrast, grade II or III gliomas are invasive and progress to higher degrees of lesions. Diffuse grade II and III gliomas are usually less aggressive than higher grade tumors, with a median survival of more than seven years [7]. There is significant heterogeneity among grade II and III gliomas in terms of pathological features and clinical results. WHO grade IV tumors (glioblastomas), the most invasive form, have the worse prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5% after initial diagnosis. After resection of primary glioblastoma, local recurrences may occur in the area of the removed tumor lesion due to the character of tumor growth and formation because of the presence of tumor cells in the adjacent pre-tumor area. Primary glioblastoma develops rapidly without preceding low-grade lesions, while secondary glioblastoma slowly progresses from diffuse or anaplastic astrocytoma (grades II and III according to the WHO classification). Primary and secondary glioblastoma differ genetically rather than histologically [4][8].

Different subtypes of gliomas have different aggressiveness spectra and responses to therapeutic treatments. The identification of a particular malignancy into a particular class has long been determined by histological characteristics supported by ancillary tissue-based tests (e.g., immunohistochemical, ultrastructural). However, diagnosis based on histology is subject to much variability between observers. In addition to the diagnostic problems, traditional diagnostic/classification schemes have fallen short of prognostic accuracy, even for patients with the same diagnosis (e.g., grade IV glioblastoma), where survival rates can vary from weeks or months to several years [8][9][10]. In addition, research performed in the last decade has shown that the impact of molecular genetic changes on disease outcome is more significant than some changes in the therapeutic treatment. The development of advanced molecular diagnostic techniques has led to a better understanding of the genomic drivers involved in gliomagenesis and their important prognostic values. The fifth edition of the 2021 WHO Classification of Primary CNS Tumors makes important changes that enhance the role of molecular diagnosis in the classification of CNS tumors [4][5]. For each tumor type, different molecular targeted markers are characterized. Taken/evaluated together these molecular markers allow the risk stratification of patients with CNS tumors in terms of prognosis and response to treatment.

3. Telomeres, Telomerase, and the TERT Promoter

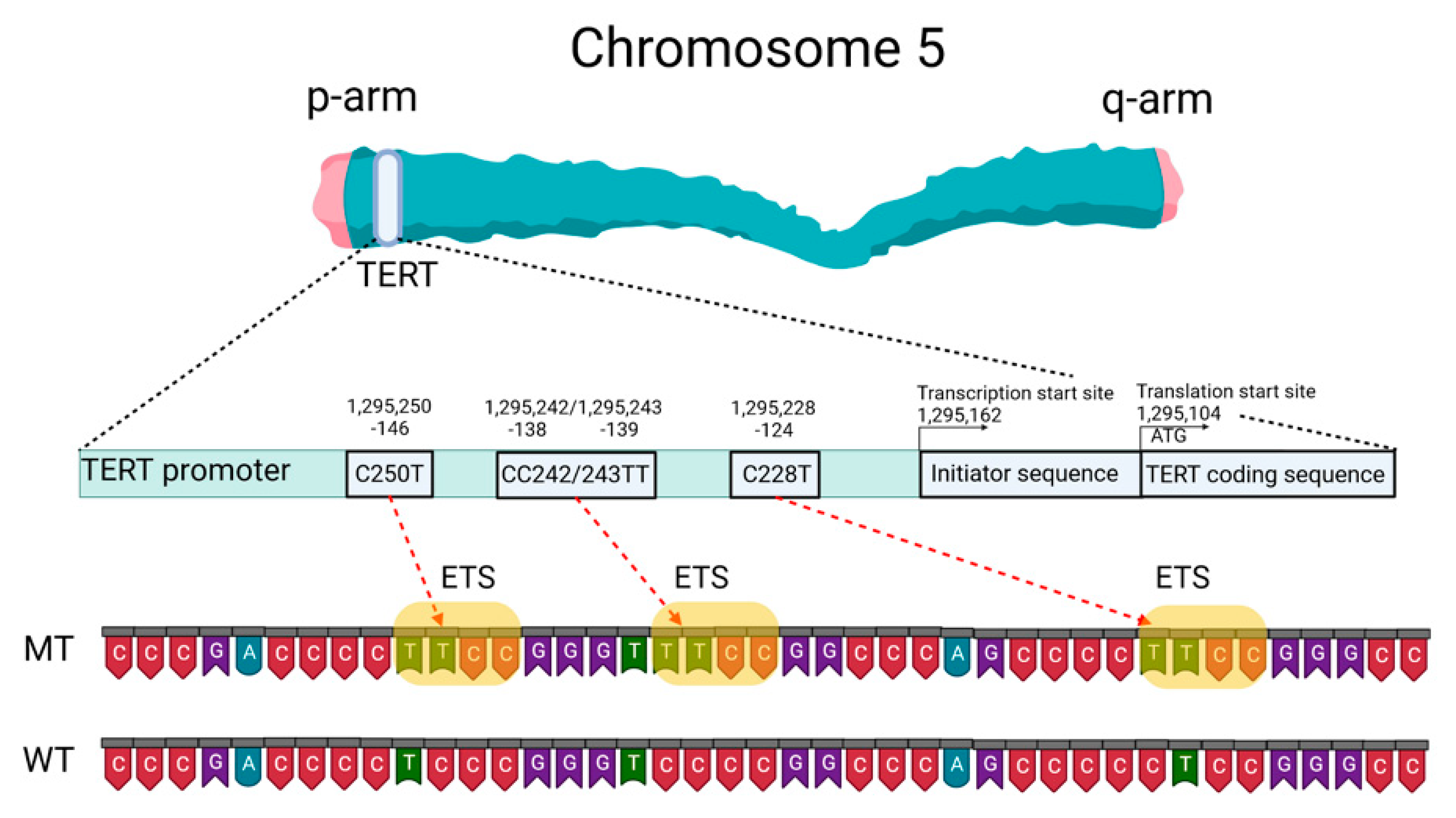

Mutations of the TERTp are known to be absent in normal human cells but are often associated with malignant tumor progression and enhanced proliferation of cells. The two most common mutations in TERTp that are mutually exclusive in CNS tumors are C228T and C250T, located −124 and −146 bp, respectively, prior to the TERT transcription site (chr 51,295,228 C > T and 1,295,250 C > T, respectively, according to GRCh37.p13 genome assembly, 1,295,113 and 1,295,135 according to GRCh38.p13 assembly). The localization of these mutations on the TERTp is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of TERT gene at chromosome 5p, its promoter structure and two canonical mutations causing gliomagenesis. C > T mutation occurs at one of both positions of the TERTp (−124 and −146 to ATG for C228T and C250T, respectively) in gliomas, which create de novo ETS binding motifs. CC242/243TT is a rare mutation and has not previously been seen in gliomas; it has been observed in other types of cancer. The figure was created with BioRender.com (19 March 2021).

These TERTp mutations create new binding sites for E-26 family transcription factors tryptophan cluster factors class (ETS/TCF) and cause a two- to four-fold increase in transcription of the messenger RNA of the telomerase catalytic subunit [11]. In addition, among members of this family, mutated TERTp creates binding sites in CNS tumors for ETS1/2 [12][13] and GA-binding proteins (GABP) [11]. The binding sites for the ETS transcription factor were specified based on the JASPAR CORE database containing a set of profiles derived from published collections of experimentally determined transcription factor binding sites [14].

The main TERT promoter does not contain a TATA-box and a CAAT-box, but it includes an array of five GC-boxes surrounded by two E-boxes [15]. As a result, TERTp can form a G-quadruplex structure. G-quadruplexes of DNA (G4) are known to be a component of a complex regulatory system in both normal and pathological cells [16] and can complicate the detection of changes in the primary structure of DNA.

Somatic TERTp mutations have been observed in various forms of CNS tumors [17][18]. TERTp mutations in CNS tumors correlate with the presence of other biomarkers, such as tumor suppressor protein 53 (TP53) gene mutations, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2 (IDH1/IDH2) gene mutations, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) changes resulting in overexpression, co-deletion of chromosomal arms 1p and 19q (1p/19q co-deletion), O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) gene promoter methylation status (MGMTp), and nuclear alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation X-linked syndrome (ATRX) gene mutations [3]. According to Powter et al., gliomas of low malignancy had the highest rate of co-detection of TERTp and IDH1/2 mutations (87.3%), while glioblastomas had a low frequency (joint detection of TERTp and IDH1/2 mutations 11.5%). Tumors (TERTp-mut + IDH-wt) were significantly associated with EGFR amplification (44.1%). A total of 54.6% of low-grade gliomas, 71.4% of glioblastomas, and all anaplastic gliomas had TERTp and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) co-mutations. TERTp-mut and MGMTp hypermethylation accounted for 51% in low-grade gliomas and 43.6% in glioblastomas. TERTp-mut is identified in 87.9% of gliomas with a 1p/19q co-deletion. TERTp-mut is associated with the suppressor/enhancer of Lin-12-like (SEL1L) overexpression. All parameters correlate with overall survival (OS) prognosis [3].

Mutations in TERTp causing an increase in telomerase activity and telomere elongation are observed in both the most aggressive form of diffuse glioma, astrocytoma, and the least aggressive form, oligodendroglioma. Hence, telomere maintenance may be a necessary precondition for the formation of CNS tumors [19]. Considering the use of TERTp mutations as a diagnostic or prognostic marker of CNS tumors is therefore highly relevant.

4. Telomere Length as a Prognostic Factor for Patients with CNS Tumors

Indirectly, mutations in the TERT gene promoter lead to telomere elongation. Gao and colleagues [20] measured the relative telomere length of 23 grade I gliomas, which are considered “borderline tumors” (most scientists believe it can be cured after surgery) and showed that telomere length had a significant impact on the survival prognosis for patients. None of the eight patients with short telomere tumor cells died, versus 6 of 15 (40%) patients with long telomeres (died). These results confirm that telomere length may be an important predictor of clinical results in low-grade gliomas of malignancy patients. According to these results, longer telomeres are more typical for gliomas than for meningiomas. TERTp mutations and longer telomeres were predictors of worse survival for glioma patients regardless of gender, age, severity, IDH1 and MGMTp status, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Co-detected TERTp mutations (TERTp-mut) and telomere elongation are associated with a worse prognosis in patients more frequently than those detected individually. Notably, patients with TERTp-mut, especially those with C228T, or patients with elongated telomeres, were resistant to radiotherapy. Gao and colleagues revealed that telomere length was significantly shorter in TERTp-mut cases than in cases with an unchanged promoter sequence (TERTp-wt) [20]. Heidenreich and colleagues also showed that telomere length is shorter in gliomas with TERTp-mut compared to gliomas without TERTp-mut [21].

Whether TERTp mutations are an early or late event in the genesis of CNS tumors has not yet been fully clarified and requires additional investigations. A recent analysis of patients with bladder cancer showed that mutations in TERTp could be detected in urine samples ten years before the initial clinical diagnosis of bladder cancer. These mutations were absent among comparable control groups that did not develop cancer for 10 years after sampling [22]. Wang and colleagues detected the mutation in both benign follicular thyroid adenoma and precancerous lesions or follicular tumors with atypical thyroid adenoma or uncertain malignancy potential [23][24]. The frequency of TERTp mutations in the above precancerous lesions was 17%, the same as that of its fully transformed analog of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Importantly, all mutation-carrying malignancies discussed express TERT mRNA and exhibit telomerase activity, which proves that telomerase reactivation occurs within early oncogenic thyroid lesions. Similarly, TERTp mutation has been identified as an early event in transforming precancerous hepatocellular carcinoma nodules in liver cirrhosis, melanoma, and urothelial papilloma [25][26][27]. At present, it is unclear exactly how TERTp mutations occur in early oncogenic lesions and completely transformed cells. Although the TERT overexpression level is typically observed in tumors, those with TERTp-mut have shorter telomeres than non-cancerous tissues. This fact indicates that TERTp mutations can represent a later event in oncogenesis (second phase) when telomere length has already been depleted [16][17]. Another hypothesis suggests that somatic mutations in cells are accumulating at a constant rate throughout life [28]. Whole genome sequencing data analysis of the Cancer Genome Atlas data of adult diffuse glioma did not show that TERTp mutations are associated with increased telomere length in grade II–III–IV diffuse gliomas [29] which argues for an early oncogenic step in this lesion. Abou and colleagues suggested that glioblastoma develops early from a common precursor with loss of at least one copy of the PTEN gene (heterozygous deletion) and a TERTp mutation: this assumption is based on the high frequency of their co-detection in gliomas [30].

5. Mutation Status of the TERT Promoter as a Prognostic Marker

The latest edition of the WHO Classification of Primary CNS Tumors in 2021 defined changes in the promoter region of the TERT gene as one of the key molecular diagnostic markers in the classification of CNS tumors for their treatment [4][5][6]. In three types of primary tumors (oligodendroglioma, glioblastoma, and meningioma), TERTp-mut is one of the diagnostic parameters. Furthermore, the combined detection of TERTp-mut and IDH1/2-mut is considered an alternative feature of oligodendroglioma.

TERTp mutations are the most frequent genomic changes in CNS tumors. Arita and colleagues investigated the presence of mutations in TERTp in a series of 546 gliomas [18]. They found a high frequency of mutually exclusive mutations located at common sites, C228T and C250T in all subtypes of the analyzed CNS tumors, of different classes in an average of 55% of all cases. The frequency of mutations was particularly high among primary glioblastomas (70%) and oligodendrogliomas (74%) but relatively low among diffuse astrocytomas (19%) and anaplastic astrocytomas (25%). A similar percentage distribution was shown by a meta-analytic approach (bibliography search) carried out in 2016: TERTp-mut was frequently found in glioblastoma (69%) and oligodendroglioma (72%), but less frequently in astrocytomas (24%) and oligoastrocytomas (38%) [31]. Other research has also evaluated the incidence of TERT mutations in different types of gliomas. Based on these data, TERT mutations are the most frequently found in glioblastoma (WHO grade IV), oligodendroglioma (WHO grade II), and oligoastrocytoma (WHO grade II), and are also frequently found in diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II), anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO grade III), anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (WHO grade III), and anaplastic oligodendroglioma (WHO grade III) [18][21][31][32][33][34][35][36][37]. The data are summarized in Table 1. In comparison to CNS tumors in adults, TERTp mutations were exceedingly rare in tumors typically encountered in pediatric patients [38].

Table 1. Frequency of TERT mutations in different types of gliomas (type of mutation TERTp: C228T and C250T, respectively).

| Authors: | Arita et al. [18] | Heidenreich et al. [21] | Yuan et al. [31] | Arita et al. [32] | Pekmezci et al. [33] | Yang et al. [34] | Kim et al. [35] | You et al. [36] | Huang et al. [37] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis: | ||||||||||

| Diffuse astrocytoma | 19% | 29% | 33% | 20% | ||||||

| Anaplastic astrocytoma | 25% | 33% | 33% | 30% | 32% | 33% | ||||

| Astrocytoma | 39% | 24% | 22% | 7% | 11% | |||||

| Glioblastoma | 70% | 80% | 69% | 58% | 66% | 64% | 42% | 84% | ||

| Oligoastrocytoma | 36% | 38% | 49% | 54% | 54% | |||||

| Anaplastic oligoastrocytoma | 40% | 44% | 42% | 41% | ||||||

| Oligodendroglioma | 74% | 70% | 72% | 83% | 96% | 74% | 76% | 70% | ||

| Anaplastic oligodendroglioma |

74% | 74% | 67% | 100% | 53% | |||||

| Number of patients in the research | 546 | 303 | 3477 | 758 | 1208 | 377 | 67 | 684 | 204 | |

According to the data presented in Table 1, the molecular profiles of low- and high-grade gliomas have different frequencies of TERTp mutations regardless of tumor class. For example, the highest frequency of TERTp mutations was found in glioblastomas (WHO grade IV) with an average frequency of 70%, oligodendrogliomas (WHO grade II) with an average frequency of 77%, and anaplastic oligodendrogliomas (WHO grade III) with an average frequency of 74%. At the same time, the lowest frequency of TERTp mutations was found in diffuse astrocytoma (WHO grade II) with an average frequency of 25%, anaplastic astrocytoma (WHO grade III) with an average frequency of 31%, oligoastrocytoma (WHO grade II) with an average frequency of 46%, and anaplastic oligoastrocytoma (WHO grade III) with an average frequency of 42% [18][21][31][32][33][34][35][36][37].

The most frequent point mutation among gliomas with TERTp-mut was C228T, in ¾ of the cases. Although C228T and C250T mutations have been reported to be mutually exclusive in CNS tumors, Nonoguchi and colleagues found C228T and C250T co-mutations in only 1 case among 322 IDH-wt glioblastomas in which mutations in both sites were found, with a frequency of 0.31% (1/322). In this study, authors examined TERTp-mut in C228T and C250T using a cohort of 358 glioblastoma cases in a population-based study that included 36 IDH-mut glioblastoma cases [39]. The fact that C228T and C250T mutations are mutually exclusive in gliomas suggests that they are each individually sufficient to play a significant oncogenic role in the pathogenesis of gliomas.

Both C228T and C250T mutations generate identical sequences, provide ETS family transcription factor binding, and are equally effective in enhancing TERT transcription. In vivo, the −124 C > T mutation was associated with higher TERT expression in glioblastoma [11]. This may indicate that the ETS/TCF binding site at the −124 position provides a more favorable/available access point for the transcriptional machinery [11]. Thus, despite similar far-reaching effects, the two canonical TERTp mutations can distinctly alter the biology of TERT expression. The mechanism(s) mediating the induction of TERT transcription in cells carrying these mutations remains poorly understood. Perhaps the two TERTp mutations generating the same ETS binding site are functionally different in the sense that C250T, unlike C228T, is similarly controlled by noncanonical NF-κB signal transduction [12].

It is also known that these mutations are absent in benign tumors and in tissues of healthy individuals [1]. Akyerli et al. identified several clinical correlations of TERTp-mut in patients with gliomas [40]. Mutations were present in more than half (52.7%) of patients, and TERTp-mut C228T patients showed lower OS compared to TERTp-mut C250T patients. TERTp-muts were found to be homogeneously present in the tumors but not in the surrounding brain parenchyma. TERTp-mut tumor status did not change over time despite adjuvant therapy or recurrence. The above allows considering TERTp mutation status as a reliable diagnostic and prognostic factor for CNS tumors.

Hewer and colleagues proposed a technique combining IDH1/IDH2 and TERTp (C228T, C250T) mutations assays to distinguish diffuse gliomas from reactive gliosis. The TERTp mutation assay was successfully applied to distinguish gliomas from gliosis for older adults. TERTp mutations were not detected in any of the 58 (0%) reactive gliosis samples and in 91 of 117 (78%) IDH wild-type gliomas. Furthermore, based on a series of 200 consecutive diffuse gliomas, they found that the IDH mutation assay only had a sensitivity of 28% to detect gliomas, whereas the combined assay yielded a sensitivity of 85% [41].

A correlation between the occurrence of TERTp mutation and OS in patients with glioma was reported [33][40]. Generally, for patients with high malignancy glioma, the group with TERTp-mut has a significantly worse OS compared to the TERTp-wt group. However, gliomas harboring TERTp mutations are often classified as grade IV gliomas because they initially have a worse predicted OS: only 39 tumors out of 406 (9.6%) in the Eckel-Passow and colleagues research were grade II or III [19]. When the cohort was considered only for glioblastoma (the most aggressive form of glioma), the following was observed: patients with TERTp-mut had a shorter OS (11 months) compared to patients with TERTp-wt (20 months) [42]. Nonoguchi and colleagues showed that TERTp-mut status had no effect on OS in glioblastomas when adjusted for other genetic changes and that the prognostic value of TERTp mutations was largely due to their inverse correlation with IDH1 mutations [39]. In low-grade gliomas, the prognostic value of the TERTp mutation clearly depends on the mutational status of IDH1/2. Yang and colleagues reported that the TERTp mutation is a prognostic factor for good OS in grade II/III gliomas, 70–90% of which harbor IDH mutations [34]. Some inconsistency in the assessment of the prognostic value of TERTp mutations may be due to insufficient cohort size or different treatment procedures in the evaluated cohorts. For example, the presence of TERTp-mut is strongly associated with diagnosis at an older age, which in itself is a well-known prognostic factor and influences treatment decisions.

Summarizing this section, can TERTp mutation status be considered an independent biomarker of primary glioma? Currently, this question cannot be answered definitively. A potential negative independent prognostic impact of TERTp mutations was identified; the deleterious effect of TERTp-mut is correlated with the presence of associated molecular and clinical factors, such as older age, IDH-wt status, and MGMTp hypermethylation [43]. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that TERTp mutations are a significant prognostic marker in other cancers (e.g., melanoma, thyroid cancer, urothelial carcinoma) and are independent of other mutations. The currently known data show that the prognostic impact of the presence of TERTp-mut in CNS tumors depends largely on the context of the histological and genomic background of the tumor, primarily the IDH status [44], and the methodology for determining mutations in the promoter region of the TERT gene.

References

- Huang, F.W.; Hodis, E.; Xu, M.J.; Kryukov, G.V.; Chin, L.; Garraway, L.A. Highly recurrent TERT promoter mutations in human melanoma. Science 2013, 339, 957–959.

- Hafezi, F.; Perez Bercoff, D. The Solo Play of TERT Promoter Mutations. Cells 2020, 9, 749.

- Powter, B.; Jeffreys, S.A.; Sareen, H.; Cooper, A.; Brungs, D.; Po, J.; Roberts, T.; Koh, E.S.; Scott, K.F.; Sajinovic, M.; et al. Human TERT promoter mutations as a prognostic biomarker in glioma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 1007–1017.

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251.

- Wen, P.Y.; Packer, R.J. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: Clinical implications. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1215–1217.

- Śledzińska, P.; Bebyn, M.G.; Furtak, J.; Kowalewski, J.; Lewandowska, M.A. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in Gliomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10373.

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Patil, N.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2013–2017. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 22 (Suppl. 2), iv1–iv96.

- Chen, R.; Smith-Cohn, M.; Cohen, A.L.; Colman, H. Glioma Subclassifications and Their Clinical Significance. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 284–297.

- Riemenschneider, M.J.; Reifenberger, G. Molecular neuropathology of gliomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 184–212.

- Zhang, P.; Xia, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Dong, L. Current Opinion on Molecular Characterization for GBM Classification in Guiding Clinical Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 562798.

- Bell, R.J.A.; Rube, H.T.; Kreig, A.; Mancini, A.; Fouse, S.D.; Nagarajan, R.P.; Choi, S.; Hong, C.; He, D.; Pekmezci, M.; et al. The transcription factor GABP selectively binds and activates the mutant TERT promoter in cancer. Science 2015, 348, 1036–1039.

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Q.L.; Sun, W.; Chandrasekharan, P.; Cheng, H.S.; Ying, Z.; Lakshmanan, M.; Raju, A.; Tenen, D.G.; Cheng, S.Y.; et al. Non-canonical NF-κB signalling and ETS1/2 cooperatively drive C250T mutant TERT promoter activation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 10, 1327–1338.

- Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Bharath, S.R.; Ozturk, M.B.; Bowler, M.W.; Loo, B.Z.L.; Tergaonkar, V.; Song, H. Structural basis for reactivating the mutant TERT promoter by cooperative binding of p52 and ETS1. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3183.

- Castro-Mondragon, J.A.; Riudavets-Puig, R.; Rauluseviciute, I.; Lemma, R.B.; Turchi, L.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; Lucas, J.; Boddie, P.; Khan, A.; Pérez, N.M.; et al. JASPAR 2022: The 9th release of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D165–D173.

- Yuan, X.; Larsson, C.; Xu, D. Mechanisms underlying the activation of TERT transcription and telomerase activity in human cancer: Old actors and new players. Oncogene 2019, 38, 6172–6183.

- Pavlova, A.V.; Kubareva, E.A.; Monakhova, M.V.; Zvereva, M.I.; Dolinnaya, N.G. Impact of G-Quadruplexes on the Regulation of Genome Integrity, DNA Damage and Repair. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1284.

- Killela, P.J.; Reitman, Z.J.; Jiao, Y.; Bettegowda, C.; Agrawal, N.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Friedman, A.H.; Friedman, H.; Gallia, G.L.; Giovanella, B.C.; et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6021–6026.

- Arita, H.; Narita, Y.; Fukushima, S.; Tateishi, K.; Matsushita, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Miyakita, Y.; Ohno, M.; Collins, V.P.; Kawahara, N.; et al. Upregulating mutations in the TERT promoter commonly occur in adult malignant gliomas and are strongly associated with total 1p19q loss. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 267–276.

- Eckel-Passow, J.; Lachance, D.; Molinaro, A.; Walsh, K.; Decker, P.; Sicotte, H.; Pekmezci, M.; Rice, T.; Kosel, M.; Smirnov, I.; et al. Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2499–2508.

- Gao, K.; Li, G.; Qu, Y.; Wang, M.; Cui, B.; Ji, M.; Shi, B.; Hou, P. TERT promoter mutations and long telomere length predict poor survival and radiotherapy resistance in gliomas. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 8712–8725.

- Heidenreich, B.; Rachakonda, S.; Hosen, I.; Volz, F.; Hemminki, K.; Weyerbrock, A.; Kumar, R. TERT promoter mutations and telomere length in adult malignant gliomas and recurrences. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 10617–10633.

- Hosen, I.; Sheikh, M.; Zvereva, M.; Scelo, G.; Forey, N.; Durand, G.; Voegele, C.; Poustchi, H.; Khoshnia, M.; Roshandel, G.; et al. Urinary TERT promoter mutations are detectable up to 10 years prior to clinical diagnosis of bladder cancer: Evidence from the Golestan Cohort Study. EBioMedicine 2020, 53, 102643.

- Wang, N.; Liu, T.; Sofiadis, A.; Juhlin, C.C.; Zedenius, J.; Höög, A.; Larsson, C.; Xu, D. TERT promoter mutation as an early genetic event activating telomerase in follicular thyroid adenoma (FTA) and atypical FTA. Cancer 2014, 120, 2965–2979.

- Hysek, M.; Paulsson, J.O.; Jatta, K.; Shabo, I.; Stenman, A.; Höög, A.; Larsson, C.; Zedenius, J.; Juhlin, C.C. Clinical Routine TERT Promoter Mutational Screening of Follicular Thyroid Tumors of Uncertain Malignant Potential (FT-UMPs): A Useful Predictor of Metastatic Disease. Cancers 2019, 11, 1443.

- Nault, J.C.; Calderaro, J.; Di Tommaso, L.; Balabaud, C.; Zafrani, E.S.; Bioulac-Sage, P.; Roncalli, M.; Zucman-Rossi, J. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutation is an early somatic genetic alteration in the transformation of premalignant nodules in hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis. Hepatology 2014, 60, 1983–1992.

- Shain, A.H.; Yeh, I.; Kovalyshyn, I.; Sriharan, A.; Talevich, E.; Gagnon, A.; Dummer, R.; North, J.P.; Pincus, L.B.; Ruben, B.S.; et al. The Genetic Evolution of Melanoma from Precursor Lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1926–1936.

- Cheng, L.; Montironi, R.; Lopez-Beltran, A. TERT Promoter Mutations Occur Frequently in Urothelial Papilloma and Papillary Urothelial Neoplasm of Low Malignant Potential. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 497–498.

- Mitchell, T.; Turajlic, S.; Rowan, A.; Nicol, D.; Farmery, J.H.; O’Brien, T.; Martincorena, I.; Tarpey, P.; Angelopoulos, N.; Yates, L.R.; et al. Timing the Landmark Events in the Evolution of Clear Cell Renal Cell Cancer: TRACERx Renal. Cell 2018, 173, 611–623.e17.

- Ceccarelli, M.; Barthel, F.; Malta, T.; Sabedot, T.S.; Salama, S.; Murray, B.A.; Morozova, O.; Newton, Y.; Radenbaugh, A.; Pagnotta, S.M.; et al. Molecular Profiling Reveals Biologically Discrete Subsets and Pathways of Progression in Diffuse Glioma. Cell 2016, 164, 550–563.

- Abou-El-Ardat, K.; Seifert, M.; Becker, K.; Eisenreich, S.; Lehmann, M.; Hackmann, K.; Rump, A.; Meijer, G.; Carvalho, B.; Temme, A.; et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of multifocal glioblastoma proves its monoclonal origin and reveals novel insights into clonal evolution and heterogeneity of glioblastomas. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 19, 546–557.

- Yuan, Y.; Qi, C.; Maling, G.; Xiang, W.; Yanhui, L.; Ruofei, L.; Yunhe, M.; Jiewen, L.; Qing, M. TERT mutation in glioma: Frequency, prognosis and risk. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 26, 57–62.

- Arita, H.; Yamasaki, K.; Matsushita, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Shimokawa, A.; Takami, H.; Tanaka, S.; Mukasa, A.; Shirahata, M.; Shimizu, S.; et al. A combination of TERT promoter mutation and MGMT methylation status predicts clinically relevant subgroups of newly diagnosed glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 79.

- Pekmezci, M.; Rice, T.; Molinaro, A.M.; Walsh, K.; Decker, P.A.; Hansen, H.; Sicotte, H.; Kollmeyer, T.M.; McCoy, L.S.; Sarkar, G.; et al. Adult infiltrating gliomas with WHO 2016 integrated diagnosis: Additional prognostic roles of ATRX and TERT. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 1001–1016.

- Yang, P.; Cai, J.; Yan, W.; Yang, P.; Cai, J.; Yan, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Li, G.; et al. Classification based on mutations of TERT promoter and IDH characterizes subtypes in grade II/III gliomas. Neuro-Oncology 2016, 18, 1099–1108.

- Kim, H.S.; Kwon, M.J.; Song, J.H.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Min, K.W. Clinical implications of TERT promoter mutation on IDH mutation and MGMT promoter methylation in diffuse gliomas. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2018, 214, 881–888.

- You, H.; Wu, Y.; Chang, K.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Yan, W.; Li, R. Paradoxical prognostic impact of TERT promoter mutations in gliomas depends on different histological and genetic backgrounds. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 790–797.

- Huang, D.-S.; Wang, Z.; He, X.-J.; Diplas, B.H.; Yang, R.; Killela, P.J.; Meng, Q.; Ye, Z.-Y.; Wang, W.; Jiang, X.-T.; et al. Recurrent TERT promoter mutations identified in a large-scale study of multiple tumour types are associated with increased TERT expression and telomerase activation. Eur. J. Cancer 2015, 51, 969–976.

- Koelsche, C.; Sahm, F.; Capper, D.; Reuss, D.; Sturm, D.; Jones, D.T.W.; Kool, M.; Northcott, P.A.; Wiestler, B.; Böhmer, K.; et al. Distribution of TERT promoter mutations in pediatric and adult tumors of the nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 907–915.

- Nonoguchi, N.; Ohta, T.; Oh, J.E.; Kim, Y.H.; Kleihues, P.; Ohgaki, H. TERT promoter mutations in primary and secondary glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 931–937.

- Akyerli, C.B.; Yüksel, Ş.; Can, Ö.; Erson-Omay, E.Z.; Oktay, Y.; Coşgun, E.; Ülgen, E.; Erdemgil, Y.; Sav, A.; von Deimling, A.; et al. Use of telomerase promoter mutations to mark specific molecular subsets with reciprocal clinical behavior in IDH mutant and IDH wild-type diffuse gliomas. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 128, 1102–1114.

- Hewer, E.; Phour, J.; Gutt-Will, M.; Schucht, P.; Dettmer, M.S.; Vassella, E. TERT Promoter Mutation Analysis to Distinguish Glioma from Gliosis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 79, 430–436.

- Mosrati, M.A.; Malmström, A.; Lysiak, M.; Krysztofiak, A.; Hallbeck, M.; Milos, P.; Hallbeck, A.L.; Bratthäll, C.; Strandéus, M.; Stenmark-Askmalm, M.; et al. TERT promoter mutations and polymorphisms as prognostic factors in primary glioblastoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 16663–16673.

- Olympios, N.; Gilard, V.; Marguet, F.; Clatot, F.; Di Fiore, F.; Fontanilles, M. TERT Promoter Alterations in Glioblastoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 1147.

- Shu, C.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X.; Wang, J. The TERT promoter mutation status and MGMT promoter methylation status, combined with dichotomized MRI-derived and clinical features, predict adult primary glioblastoma survival. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 3704–3712.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

12 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No