| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Michał Konwerski | -- | 1842 | 2022-04-07 18:54:42 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 1842 | 2022-04-08 07:55:56 | | |

Video Upload Options

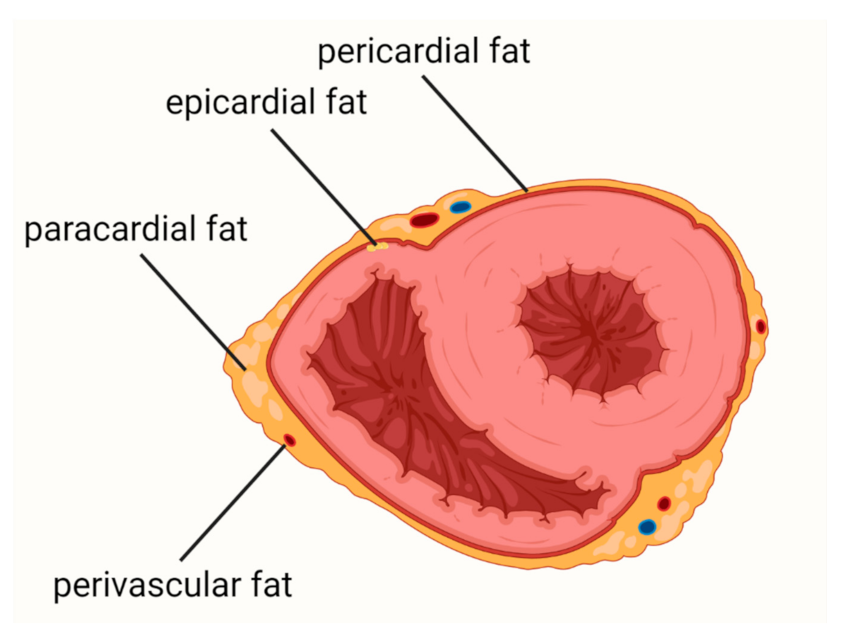

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading causes of death worldwide. Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is defined as a fat depot localized between the myocardial surface and the visceral layer of the pericardium and is a type of visceral fat. EAT is one of the most important risk factors for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events and a promising new therapeutic target in CVDs. In health conditions, EAT has a protective function, including protection against hypothermia or mechanical stress, providing myocardial energy supply from free fatty acid and release of adiponectin. In patients with obesity, metabolic syndrome, or diabetes mellitus, EAT becomes a deleterious tissue promoting the development of CVDs.

1. Introduction

2. Coronary Artery Disease

3. Heart Failure

Among patients with HF, approximately 50% have preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). HFpEF is a heterogeneous disease with a complex pathogenesis which is not fully understood. This complexity is due to the fact that it can be caused or exacerbated by a variety of comorbidities, including cardiac and extracardiac abnormalities. Thus, the group of patients with HFpEF is very diverse [51][52]. HFpEF is the most common myocardium disorder among obese patients [53].

Based on the hitherto studies, it can be concluded that: (i) there is an association between EATV and the development of HfpEF; (ii) patients with HFpEF and obesity represent a distinct phenotype of the disease; (iii) EAT thickness or volume may have a greater impact on HFpEF than obesity per se; (iv) EAT participates in the pathogenesis of HfpEF due to EAT’s proinflammatory properties, intensification of fibrosis, and influence on myocardial substrate utilization.

There is a correlation between the severity of left ventricle (LV) diastolic dysfunction and the volume of EAT [54][55][56].

Patients with coexisting obesity and HFpEF had a different clinical phenotype than patients with HFpEF without obesity [57]. Obokata et al. compared patients with HFpEF and obesity, HPpEF without obesity, and a non-obese control group without HF [57]. Among obese HFpEF patients, diabetes and sleep apnea were more prevalent, whereas in the non-obese HFpEF patients, atrial fibrillation was more common. Additionally, the obese HFpEF patients had lower concentrations of N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), compared to the non-obese cohort. Furthermore, subjects with the obese HFpEF phenotype had increased plasma volume, a higher rate of concentric LV remodeling, greater right ventricular (RV) dilatation, and a higher rate of RV dysfunction. Obese patients also displayed worse exercise capacity, more pronounced hemodynamic abnormalities during exercise, and impaired pulmonary vasodilation. EAT thickness assessed by echocardiography was 20% higher in the obese HF group compared to non-obese HF, and 50% higher compared to the control group [57].

In obese patients with increased plasma volume, the ability of LV to dilate is insufficient, leading to cardiac overfilling and disproportionate increases in cardiac filling pressures. It seems that the inadequate ventricular distensibility is caused by cardiac fibrosis and microvascular rarefaction [58][59]. Moreover, the quantity of fibrosis assessed in CMR is associated with prognosis and outcomes in HFpEF [60]. Obese patients displayed more EAT [8][9] and therefore it seems likely that they were more exposed to cytokines released from the EAT reservoir.

4. Atrial Fibrillation

References

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Carson, A.P.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Delling, F.N.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 141, e139–e596.

- Heron, M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2013. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2016, 68, 1–77.

- Fryar, C.D.; Chen, T.-C.; Li, X. Prevalence of Uncontrolled Risk Factors for Cardiovascular Disease: United States, 1999–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012, 103, 1–8.

- Sacks, H.S.; Fain, J.N. Human epicardial adipose tissue: A review. Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 907–917.

- Mathieu, P.; Pibarot, P.; Larose, É.; Poirier, P.; Marette, A.; Després, J.-P. Visceral obesity and the heart. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 821–836.

- Mathieu, P.; Lemieux, I.; Després, J.-P. Obesity, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Risk. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 87, 407–416.

- Després, J.-P.; Lemieux, I. Abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. Nature 2006, 444, 881–887.

- Rabkin, S.W. Epicardial fat: Properties, function and relationship to obesity. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 253–261.

- Iacobellis, G.; Willens, H.J.; Barbaro, G.; Sharma, A.M. Threshold values of high-risk echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness. Obesity 2008, 16, 887–892.

- Mahabadi, A.A.; Berg, M.H.; Lehmann, N.; Kälsch, H.; Bauer, M.; Kara, K.; Dragano, N.; Moebus, S.; Jöckel, K.-H.; Erbel, R.; et al. Association of Epicardial Fat with Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Incident Myocardial Infarction in the General Population. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 1388–1395.

- Mazurek, T.; Opolski, G. Pericoronary Adipose Tissue: A Novel Therapeutic Target in Obesity-Related Coronary Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2015, 34, 244–254.

- Mazurek, K.; Zmijewski, P.; Krawczyk, K.; Czajkowska, A.; Kęska, A.; Kapuściński, P.; Mazurek, T. High intensity interval and moderate continuous cycle training in a physical education programme improves health-related fitness in young females. Biol. Sport 2016, 33, 139–144.

- Nagy, E.; Jermendy, A.L.; Merkely, B.; Maurovich-Horvat, P. Clinical importance of epicardial adipose tissue. Arch. Med Sci. 2017, 4, 864–874.

- Zhang, L.; Zalewski, A.; Liu, Y.; Mazurek, T.; Cowan, S.; Martin, J.L.; Hofmann, S.M.; Vlassara, H.; Shi, Y. Diabetes-Induced Oxidative Stress and Low-Grade Inflammation in Porcine Coronary Arteries. Circulation 2003, 108, 472–478.

- McAninch, E.; Fonseca, T.L.; Poggioli, R.; Panos, A.; Salerno, T.A.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Bianco, A.; Iacobellis, G. Epicardial adipose tissue has a unique transcriptome modified in severe coronary artery disease. Obesity 2015, 23, 1267–1278.

- Iacobellis, G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 363–371.

- Mazurek, T.; Zhang, L.; Zalewski, A.; Mannion, J.D.; Diehl, J.T.; Arafat, H.; Sarov-Blat, L.; O’Brien, S.; Keiper, E.A.; Johnson, A.G.; et al. Human Epicardial Adipose Tissue Is a Source of Inflammatory Mediators. Circulation 2003, 108, 2460–2466.

- Sacks, H.S.; Fain, J.N.; Holman, B.; Cheema, P.; Chary, A.; Parks, F.; Karas, J.; Optican, R.; Bahouth, S.W.; Garrett, E.; et al. Uncoupling Protein-1 and Related Messenger Ribonucleic Acids in Human Epicardial and Other Adipose Tissues: Epicardial Fat Functioning as Brown Fat. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 3611–3615.

- Prati, F.; Arbustini, E.; Labellarte, A.; Sommariva, L.; Pawlowski, T.; Manzoli, A.; Pagano, A.; Motolese, M.; Boccanelli, A. Eccentric atherosclerotic plaques with positive remodelling have a pericardial distribution: A permissive role of epicardial fat? A three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound study of left anterior descending artery lesions. Eur. Heart J. 2003, 24, 329–336.

- Iacobellis, G.; Bianco, A. Epicardial adipose tissue: Emerging physiological, pathophysiological and clinical features. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 22, 450–457.

- Iozzo, P. Metabolic toxicity of the heart: Insights from molecular imaging. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 147–156.

- Li, R.; Wang, W.-Q.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Fan, Q.; Christopher, T.A.; Lopez, B.L.; Tao, L.; Goldstein, B.J.; Gao, F.; et al. Adiponectin improves endothelial function in hyperlipidemic rats by reducing oxidative/nitrative stress and differential regulation of eNOS/iNOS activity. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2007, 293, E1703–E1708.

- Deng, G.; Long, Y.; Yum, Y.R.; Li, M.R. Adiponectin directly improves endothelial dysfunction in obese rats through the AMPK-eNOS pathway. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 165–171.

- Niedziela, M.; Wojciechowska, M.; Zarębiński, M.; Cudnoch-Jędrzejewska, A.; Mazurek, T. Adiponectin promotes ischemic heart preconditioning-PRO and CON. Cytokine 2020, 127, 154981.

- Eiras, S.; Teijeira-Fernández, E.; Shamagian, L.G.; Fernandez, A.L.; Vazquez-Boquete, A.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R. Extension of coronary artery disease is associated with increased IL-6 and decreased adiponectin gene expression in epicardial adipose tissue. Cytokine 2008, 43, 174–180.

- Iacobellis, G.; Pistilli, D.; Gucciardo, M.; Leonetti, F.; Miraldi, F.; Brancaccio, G.; Gallo, P.; Di Gioia, C.R.T. Adiponectin expression in human epicardial adipose tissue in vivo is lower in patients with coronary artery disease. Cytokine 2005, 29, 251–255.

- Raman, P.; Khanal, S. Leptin in Atherosclerosis: Focus on Macrophages, Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5446.

- Iacobellis, G.; Malavazos, A.E.; Corsi, M.M. Epicardial fat: From the biomolecular aspects to the clinical practice. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 1651–1654.

- Wolf, D.; Ley, K. Immunity and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 315–327.

- Virmani, R.; Burke, A.P.; Farb, A.; Kolodgie, F.D. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, C13–C18.

- Tavora, F.; Kutys, R.; Li, L.; Ripple, M.; Fowler, D.; Burke, A. Adventitial lymphocytic inflammation in human coronary arteries with intimal atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2010, 19, e61–e68.

- Wang, C.P.; Hsu, H.L.; Hung, W.C.; Yu, T.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Chiu, C.A.; Lu, L.F.; Chung, F.M.; Shin, S.J.; Lee, Y.J. Increased epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) volume in type 2 diabetes mellitus and association with metabolic syndrome and severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Clin. Endocrinol. 2009, 70, 876–882.

- Rosito, G.A.; Massaro, J.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Ruberg, F.L.; Mahabadi, A.A.; Vasan, R.S.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Fox, C.S. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008, 117, 605–613.

- Alexopoulos, N.; McLean, D.S.; Janik, M.; Arepalli, C.D.; Stillman, A.E.; Raggi, P. Epicardial adipose tissue and coronary artery plaque characteristics. Atherosclerosis 2010, 210, 150–154.

- Yamashita, K.; Yamamoto, M.H.; Igawa, W.; Ono, M.; Kido, T.; Ebara, S.; Okabe, T.; Saito, S.; Amemiya, K.; Isomura, N.; et al. Association of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Volume and Total Coronary Plaque Burden in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Int. Heart J. 2018, 59, 1219–1226.

- Mazurek, T.; Kochman, J.; Kobylecka, M.; Wilimski, R.; Filipiak, K.J.; Krolicki, L.; Opolski, G. Inflammatory activity of pericoronary adipose tissue may affect plaque composition in patients with acute coronary syndrome without persistent ST-segment elevation: Preliminary results. Kardiol. Pol. 2013, 72, 410–416.

- Mazurek, T.; Kobylecka, M.; Zielenkiewicz, M.; Kurek, A.; Kochman, J.; Filipiak, K.J.; Mazurek, K.; Huczek, Z.; Królicki, L.; Opolski, G. PET/CT evaluation of 18F-FDG uptake in pericoronary adipose tissue in patients with stable coronary artery disease: Independent predictor of atherosclerotic lesions’ formation? J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2016, 24, 1075–1084.

- Özcan, F.; Turak, O.; Canpolat, U.; Kanat, S.; Kadife, I.; Avcı, S.; Işleyen, A.; Cebeci, M.; Tok, D.; Başar, F.; et al. Association of epicardial fat thickness with TIMI risk score in NSTEMI/USAP patients. Herz 2014, 39, 755–760.

- Otsuka, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Yamaura, H.; Shirasawa, K.; Kasayuki, N. Epicardial adipose tissue volume is associated with low-attenuation plaque volume in subjects with or without increased visceral fat: A 3-vessel coronary artery analysis with CT angiography. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42 (Suppl. 1), ehab724-0208.

- Ma, R.; van Assen, M.; Ties, D.; Pelgrim, G.J.; van Dijk, R.; Sidorenkov, G.; van Ooijen, P.M.A.; van der Harst, P.; Vliegenthart, R. Focal pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation is related to plaque presence, plaque type, and stenosis severity in coronary CTA. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 7251–7261.

- Balcer, B.; Dykun, I.; Schlosser, T.; Forsting, M.; Rassaf, T.; Mahabadi, A.A. Pericoronary fat volume but not attenuation differentiates culprit lesions in patients with myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis 2018, 276, 182–188.

- Goeller, M.; Achenbach, S.; Cadet, S.; Kwan, A.C.; Commandeur, F.; Slomka, P.J.; Gransar, H.; Albrecht, M.H.; Tamarappoo, B.K.; Berman, D.S.; et al. Pericoronary Adipose Tissue Computed Tomography Attenuation and High-Risk Plaque Characteristics in Acute Coronary Syndrome Compared with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 858–863.

- Goeller, M.; Tamarappoo, B.K.; Kwan, A.C.; Cadet, S.; Commandeur, F.; Razipour, A.; Slomka, P.J.; Gransar, H.; Chen, X.; Otaki, Y.; et al. Relationship between changes in pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation and coronary plaque burden quantified from coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 20, 636–643.

- Nogic, J.; Kim, J.; Layland, J.; Chan, J.; Cheng, K.; Wong, D.; Brown, A. TCT-241 Pericoronary Adipose Tissue Is a Predictor of In-Stent Restenosis and Stent Failure in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Stent Insertion. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78 (19 Suppl. S), B98.

- Sade, L.E.; Eroglu, S.; Bozbaş, H.; Özbiçer, S.; Hayran, M.; Haberal, A.; Muderrisoglu, I.H. Relation between epicardial fat thickness and coronary flow reserve in women with chest pain and angiographically normal coronary arteries. Atherosclerosis 2009, 204, 580–585.

- Kanaji, Y.; Sugiyama, T.; Hoshino, M.; Misawa, T.; Nagamine, T.; Yasui, Y.; Nogami, K.; Ueno, H.; Hada, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; et al. The impact of pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation on global coronary flow reserve in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1433.

- Pasqualetto, M.C.; Tuttolomondo, D.; Cutruzzolà, A.; Niccoli, G.; Dey, D.; Greco, A.; Martini, C.; Irace, C.; Rigo, F.; Gaibazzi, N. Human coronary inflammation by computed tomography: Relationship with coronary microvascular dysfunction. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 336, 8–13.

- Kataoka, T.; Harada, K.; Tanaka, A.; Onishi, T.; Matsunaga, S.; Funakubo, H.; Harada, K.; Nagao, T.; Shinoda, N.; Marui, N.; et al. Relationship between epicardial adipose tissue volume and coronary artery spasm. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021, 324, 8–12.

- Aitken-Buck, H.M.; Moharram, M.; Babakr, A.A.; Reijers, R.; Van Hout, I.; Fomison-Nurse, I.C.; Sugunesegran, R.; Bhagwat, K.; Davis, P.J.; Bunton, R.W.; et al. Relationship between epicardial adipose tissue thickness and epicardial adipocyte size with increasing body mass index. Adipocyte 2019, 8, 412–420.

- Naryzhnaya, N.V.; Koshelskaya, O.A.; Kologrivova, I.V.; Kharitonova, O.A.; Evtushenko, V.V.; Boshchenko, A.A. Hypertrophy and Insulin Resistance of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Adipocytes: Association with the Coronary Artery Disease Severity. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 64.

- Reddy, Y.N.; Borlaug, B.A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2016, 41, 145–188.

- Shah, S.J.; Kitzman, D.W.; Borlaug, B.A.; van Heerebeek, L.; Zile, M.R.; Kass, D.A.; Paulus, W.J. Phenotype-specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A multiorgan roadmap. Circulation 2016, 134, 73–90.

- Kitzman, D.W.; Shah, S.J. The HFpEF obesity phenotype: The elephant in the room. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 200–203.

- Fontes-Carvalho, R.; Fontes-Oliveira, M.; Sampaio, F.; Bettencourt, N.; Teixeira, M.; Rocha Gonçalves, F.; Gama, V.; Leite-Moreira, A. Influence of epicardial and visceral fat on left ventricular diastolic and systolic functions inpatients after myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 114, 1663–1669.

- Liu, J.; Fox, C.S.; Hickson, D.A.; May, W.L.; Ding, J.; Carr, J.J.; Taylor, H.A. Pericardial fat and echocardiographic measures of cardiac abnormalities: The Jackson Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, 341–346.

- Cavalcante, J.L.; Tamarappoo, B.K.; Hachamovitch, R.; Kwon, D.H.; Alraies, M.C.; Halliburton, S.; Schoenhagen, P.; Dey, D.; Berman, D.S.; Marwick, T.H. Association of Epicardial Fat, Hypertension, Subclinical Coronary Artery Disease, and Metabolic Syndrome with Left Ventricular Diastolic Dysfunction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 1793–1798.

- Obokata, M.; Reddy, Y.; Pislaru, S.; Melenovsky, V.; Borlaug, B.A. Evidence Supporting the Existence of a Distinct Obese Phenotype of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2017, 136, 6–19.

- Mahajan, R.; Lau, D.H.; Sanders, P. Impact of obesity on cardiac metabolism, fibrosis, and function. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2015, 25, 119–126.

- Mohammed, S.F.; Hussain, S.; Mirzoyev, S.A.; Edwards, W.D.; Maleszewski, J.J.; Redfield, M.M. Coronary Microvascular Rarefaction and Myocardial Fibrosis in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2015, 131, 550–559.

- Duca, F.; Kammerlander, A.A.; Zotter-Tufaro, C.; Aschauer, S.; Schwaiger, M.L.; Marzluf, B.A.; Bonderman, D.; Mascherbauer, J. Interstitial fibrosis, functional status, and outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Insights from a prospective cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e005277.

- Zulkifly, H.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Lane, D.A. Epidemiology of atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2018, 72, e13070.

- Schneider, M.P.; Hua, T.A.; Böhm, M.; Wachtell, K.; Kjeldsen, S.E.; Schmieder, R.E. Prevention of Atrial Fibrillation by Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibition: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 2299–2307.

- Large, S.R.; Hosseinpour, A.R.; Wisbey, C.; Wells, F.C. Spontaneous cardioversion and mitral valve repair: A role for surgical cardioversion (Cox-maze)? Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 1997, 11, 76–80.

- Hirsh, B.J.; Copeland-Halperin, R.S.; Halperin, J.L. Fibrotic atrial cardiomyo-pathy, atrial fibrillation, and thromboembolism: Mechanistic links and clinical inferences. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2239–2251.

- Watanabe, T.; Takeishi, Y.; Hirono, O.; Itoh, M.; Matsui, M.; Nakamura, K.; Tamada, Y.; Kubota, I. C-Reactive protein elevation predicts the occurrence of atrial structural remodeling in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Vessel. 2005, 20, 45–49.

- Lindhardsen, J.; Ahlehoff, O.; Gislason, G.H.; Madsen, O.R.; Olesen, J.B.; Svendsen, J.H.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Hansen, P.R. Risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke in rheumatoid arthritis: Danish nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2012, 344, e1257.

- Rhee, T.-M.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, E.-K.; Han, K.-D.; Lee, H.; Park, C.S.; Hwang, D.; Lee, S.-R.; Lim, W.-H.; Kang, S.-H.; et al. Increased Risk of Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolism in Patients with Severe Psoriasis: A Nationwide Population-based Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9973.

- Aksoy, H.; Okutucu, S.; Sayin, B.Y.; Oto, A. Non-invasive electrocardiographic methods for assessment of atrial conduction heterogeneity in ankylosing spondylitis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 2185–2186.

- Efe, T.H.; Cimen, T.; Ertem, A.G.; Coskun, Y.; Bilgin, M.; Sahan, H.F.; Pamukcu, H.E.; Yayla, C.; Sunman, H.; Yuksel, I.; et al. Atrial Electromechanical Properties in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Echocardiography 2016, 33, 1309–1316.

- Wanahita, N.; Messerli, F.H.; Bangalore, S.; Gami, A.S.; Somers, V.K.; Steinberg, J.S. Atrial fibrillation and obesity—Results of a meta-analysis. Am. Heart J. 2008, 155, 310–315.

- Huxley, R.R.; Alonso, A.; Lopez, F.L.; Filion, K.; Agarwal, S.K.; Loehr, L.; Soliman, E.Z.; Pankow, J.; Selvin, E. Type 2 diabetes, glucose homeostasis and incident atrial fibrillation: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Heart 2011, 98, 133–138.

- Graça, B.; Ferreira, M.J.; Donato, P.; Gomes, L.; Castelo-Branco, M.; Caseiro-Alves, F. Left atrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Insights from cardiac MRI. Eur. Radiol. 2014, 24, 2669–2676.

- Nyman, K.; Graner, M.; Pentikäinen, M.; Lundbom, J.; Hakkarainen, A.; Siren, R.; Nieminen, M.; Taskinen, M.-R.; Lauerma, K.; Lundbom, N. Metabolic syndrome associates with left atrial dysfunction. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 727–734.

- Chechi, K.; Voisine, P.; Mathieu, P.; Laplante, M.; Bonnet, S.; Picard, F.; Joubert, P.; Richard, D. Functional characterization of the Ucp1-associated oxidative phenotype of human epicardial adipose tissue. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15566.

- Pezeshkian, M.; Noori, M.; Najjarpour-Jabbari, H.; Abolfathi, A.; Darabi, M.; Darabi, M.; Shaaker, M.; Shahmohammadi, G. Fatty acid composition of epicardial and subcutaneous human adipose tissue. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2009, 7, 125–131.

- Kourliouros, A.; Karastergiou, K.; Nowell, J.; Gukop, P.; Hosseini, M.T.; Valencia, O.; Ali, V.M.; Jahangiri, M. Protective effect of epicardial adiponectin on atrial fibrillation following cardiac surgery. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic. Surg. 2011, 39, 228–232.

- Inoue, T.; Takemori, K.; Mizuguchi, N.; Kimura, M.; Chikugo, T.; Hagiyama, M.; Yoneshige, A.; Mori, T.; Maenishi, O.; Kometani, T.; et al. Heart-bound adiponectin, not serum adiponectin, inversely correlates with cardiac hypertrophy in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Exp. Physiol. 2017, 102, 1435–1447.

- Antonopoulos, A.S.; Margaritis, M.; Verheule, S.; Recalde, A.; Sanna, F.; Herdman, L.; Psarros, C.; Nasrallah, H.; Coutinho, P.; Akoumianakis, I.; et al. Mutual regulation of epicardial adipose tissue and myocardial redox state by PPARgamma/adiponectin signalling. Circ Res. 2016, 118, 842–855.

- Fang, F.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Tamaki, Z.; Wei, J.; Marangoni, R.G.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Summer, R.S.; Ye, B.; Varga, J. The adipokine adiponectin has potent anti-fibrotic effects mediated via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase: Novel target for fibrosis therapy. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R229.

- Vural, B.; Atalar, F.; Ciftci, C.; Demirkan, A.; Susleyici-Duman, B.; Gunay, D.; Akpinar, B.; Sagbas, E.; Ozbek, U.; Buyukdevrim, A.S. Presence of fatty-acid-binding protein 4 expression in human epicardial adipose tissue in metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc. Pathol. 2008, 17, 392–398.

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Jung, J.W.; Kim, N.S.; Noh, C.I.; Hong, Y.M. Correlation Between Epicardial Fat Thickness by Echocardiography and Other Parameters in Obese Adolescents. Korean Circ. J. 2012, 42, 471–478.

- Karastergiou, K.; Evans, I.; Ogston, N.; Miheisi, N.; Nair, D.; Kaski, J.-C.; Jahangiri, M.; Mohamed-Ali, V. Epicardial Adipokines in Obesity and Coronary Artery Disease Induce Atherogenic Changes in Monocytes and Endothelial Cells. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1340–1346.

- Bambace, C.; Sepe, A.; Zoico, E.; Telesca, M.; Olioso, D.; Venturi, S.; Rossi, A.; Corzato, F.; Faccioli, S.; Cominacini, L.; et al. Inflammatory profile in subcutaneous and epicardial adipose tissue in men with and without diabetes. Heart Vessel. 2014, 29, 42–48.

- Cheng, K.-H.; Chu, C.-S.; Lee, K.-T.; Lin, T.-H.; Hsieh, C.-C.; Chiu, C.-C.; Voon, W.-C.; Sheu, S.-H.; Lai, W.-T. Adipocytokines and proinflammatory mediators from abdominal and epicardial adipose tissue in patients with coronary artery disease. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 268–274.

- Mazurek, T.; Kiliszek, M.; Kobylecka, M.; Skubisz-Głuchowska, J.; Kochman, J.; Filipiak, K.; Krolicki, L.; Opolski, G. Relation of Proinflammatory Activity of Epicardial Adipose Tissue to the Occurrence of Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 113, 1505–1508.

- Tse, G.; Yan, B.P.; Chan, Y.W.F.; Tian, X.Y.; Huang, Y. Reactive oxygen species, endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction: The link with cardiac arrhythmogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 313.

- Kim, Y.M.; Kattach, H.; Ratnatunga, C.; Pillai, R.; Channon, K.; Casadei, B. Association of Atrial Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Oxidase Activity With the Development of Atrial Fibrillation After Cardiac Surgery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 68–74.

- Salgado-Somoza, A.; Teijeira-Fernández, E.; Fernández, Á.L.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Eiras, S. Proteomic analysis of epicardial and subcutaneous adipose tissue reveals differences in proteins involved in oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H202–H209.

- Haemers, P.; Hamdi, H.; Guedj, K.; Suffee, N.; Farahmand, P.; Popovic, N.; Claus, P.; Leprince, P.; Nicoletti, A.; Jalife, J.; et al. Atrial fibrillation is associated with the fibrotic remodelling of adipose tissue in the subepicardium of human and sheep atria. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 53–61.

- Platonov, P.; Mitrofanova, L.B.; Orshanskaya, V.; Ho, S.Y. Structural Abnormalities in Atrial Walls Are Associated with Presence and Persistency of Atrial Fibrillation But Not with Age. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2225–2232.

- Friedman, D.; Wang, N.; Meigs, J.B.; Hoffmann, U.; Massaro, J.M.; Fox, C.S.; Magnani, J.W. Pericardial Fat is Associated with Atrial Conduction: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000477.

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhao, L. Epicardial adipose tissue and atrial fibrillation: Possible mechanisms, potential therapies, and future directions. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2019, 43, 133–145.

- Shen, M.J.; Shinohara, T.; Park, H.-W.; Frick, K.; Ice, D.S.; Choi, E.-K.; Han, S.; Maruyama, M.; Sharma, R.; Shen, C.; et al. Continuous Low-Level Vagus Nerve Stimulation Reduces Stellate Ganglion Nerve Activity and Paroxysmal Atrial Tachyarrhythmias in Ambulatory Canines. Circulation 2011, 123, 2204–2212.

- Chen, P.-S.; Chen, L.S.; Fishbein, M.C.; Lin, S.F.; Nattel, S. Role of the autonomic nervous system in atrial fibrillation: Pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res. 2014, 114, 1500–1515.

- Balcioğlu, A.S.; Çiçek, D.; Akinci, S.; Eldem, H.O.; Bal, U.A.; Okyay, K.; Muderrisoglu, I.H. Arrhythmogenic Evidence for Epicardial Adipose Tissue: Heart Rate Variability and Turbulence are Influenced by Epicardial Fat Thickness. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 2015, 38, 99–106.

- Danik, S.; Neuzil, P.; D’Avila, A.; Malchano, Z.J.; Kralovec, S.; Ruskin, J.N.; Reddy, V. Evaluation of Catheter Ablation of Periatrial Ganglionic Plexi in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 102, 578–583.

- Perez, M.V.; Wang, P.J.; Larson, J.C.; Virnig, B.A.; Cochrane, B.; Curb, J.D.; Klein, L.; Manson, J.E.; Martin, L.W.; Robinson, J.; et al. Effects of postmenopausal hormone therapy on incident atrial fibrillation: TheWomen’s health initiative randomized controlled trials. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2012, 5, 1108–1116.

- Bernasochi, G.B.; Boon, W.C.; Curl, C.L.; Varma, U.; Pepe, S.; Tare, M.; Parry, L.J.; Dimitriadis, E.; Harrap, S.B.; Nalliah, C.J.; et al. Pericardial adipose and aromatase: A new translational target for aging, obesity and arrhythmogenesis? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 111, 96–101.

- Ernault, A.C.; Meijborg, V.M.F.; Coronel, R. Modulation of Cardiac Arrhythmogenesis by Epicardial Adipose Tissue: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 1730–1745.