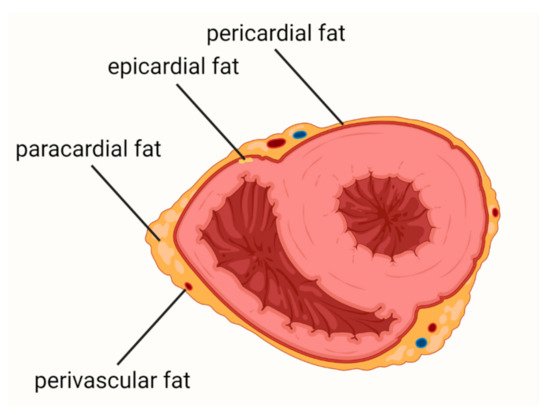

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading causes of death worldwide. Epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is defined as a fat depot localized between the myocardial surface and the visceral layer of the pericardium and is a type of visceral fat. EAT is one of the most important risk factors for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events and a promising new therapeutic target in CVDs. In health conditions, EAT has a protective function, including protection against hypothermia or mechanical stress, providing myocardial energy supply from free fatty acid and release of adiponectin. In patients with obesity, metabolic syndrome, or diabetes mellitus, EAT becomes a deleterious tissue promoting the development of CVDs.

- atherosclerosis

- cardiovascular diseases

- epicardial adipose tissue

- EAT

- inflammation

1. Introduction

2. Coronary Artery Disease

3. Heart Failure

Among patients with HF, approximately 50% have preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). HFpEF is a heterogeneous disease with a complex pathogenesis which is not fully understood. This complexity is due to the fact that it can be caused or exacerbated by a variety of comorbidities, including cardiac and extracardiac abnormalities. Thus, the group of patients with HFpEF is very diverse [52,53]. HFpEF is the most common myocardium disorder among obese patients [54].

Based on the hitherto studies, it can be concluded that: (i) there is an association between EATV and the development of HfpEF; (ii) patients with HFpEF and obesity represent a distinct phenotype of the disease; (iii) EAT thickness or volume may have a greater impact on HFpEF than obesity per se; (iv) EAT participates in the pathogenesis of HfpEF due to EAT’s proinflammatory properties, intensification of fibrosis, and influence on myocardial substrate utilization.

There is a correlation between the severity of left ventricle (LV) diastolic dysfunction and the volume of EAT [56,57,58].

Patients with coexisting obesity and HFpEF had a different clinical phenotype than patients with HFpEF without obesity [60]. Obokata et al. compared patients with HFpEF and obesity, HPpEF without obesity, and a non-obese control group without HF [60]. Among obese HFpEF patients, diabetes and sleep apnea were more prevalent, whereas in the non-obese HFpEF patients, atrial fibrillation was more common. Additionally, the obese HFpEF patients had lower concentrations of N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), compared to the non-obese cohort. Furthermore, subjects with the obese HFpEF phenotype had increased plasma volume, a higher rate of concentric LV remodeling, greater right ventricular (RV) dilatation, and a higher rate of RV dysfunction. Obese patients also displayed worse exercise capacity, more pronounced hemodynamic abnormalities during exercise, and impaired pulmonary vasodilation. EAT thickness assessed by echocardiography was 20% higher in the obese HF group compared to non-obese HF, and 50% higher compared to the control group [60].

In obese patients with increased plasma volume, the ability of LV to dilate is insufficient, leading to cardiac overfilling and disproportionate increases in cardiac filling pressures. It seems that the inadequate ventricular distensibility is caused by cardiac fibrosis and microvascular rarefaction [65,66]. Moreover, the quantity of fibrosis assessed in CMR is associated with prognosis and outcomes in HFpEF [67]. Obese patients displayed more EAT [8,9] and therefore it seems likely that they were more exposed to cytokines released from the EAT reservoir.

4. Atrial Fibrillation

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biology11030355