Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | INÉS MONTEIRA | -- | 2671 | 2022-04-01 13:48:59 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -39 word(s) | 2632 | 2022-04-02 03:18:35 | | | | |

| 3 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2632 | 2022-04-02 03:20:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Monteira, I. Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and Iberian Christian Kingdoms. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21282 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Monteira I. Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and Iberian Christian Kingdoms. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21282. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Monteira, Inés. "Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and Iberian Christian Kingdoms" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21282 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Monteira, I. (2022, April 01). Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and Iberian Christian Kingdoms. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21282

Monteira, Inés. "Artistic Interchange between Al-Andalus and Iberian Christian Kingdoms." Encyclopedia. Web. 01 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

The ivory casket made in Cuenca in A.D. 1026 and signed by Mohammad ibn Zayyan constitutes invaluable evidence for the study of artistic transfers between Al-Andalus and the Iberian Christian kingdoms. In the 12th century this piece was transformed in the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos (Burgos) with the addition of Christian-themed enamels and reused as a reliquary.

Islamic motifs in Spanish Romanesque

Ibn Zayyan ivory casket

monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos

1. Introduction: Transfers between Andalusi Art and the Spanish Romanesque

Iberian art from the 10th to the 12th centuries has been the subject of countless studies from the 19th century on due to its extraordinary richness and uniqueness. Nevertheless, a disciplinary barrier has long been present leading to the separation of Christian art from Islamic art of this period, thus converting them into two independent specialties. The border that once existed between Al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms seems to have led, to some extent, to the separate study of their respective artistic manifestations, despite their geographic and chronological proximity, and their clear connections. There are, however, significant studies about those artistic contacts, primarily in Mozarabic architecture and the illustrated Beatus commentaries. Scholars such as O.K. Werckmeister [1], H. Stierlin [2], J. Williams [3], and P. Klein [4] have analysed these interchanges. Others such as J. Zozaya [5], A. Shalem [6] and M. Rosser-Owen [7] have addressed the importance of Andalusi artworks in the Christian north. In regard to Romanesque art of the 11th and 12th centuries, these connections have been approached from multiple points of view. Scholars like É. Lambert [8], É. Mâle [9], A. Fikry [10] and K. Watson [11] have reaffirmed them, while others like X. Barral i Altet [12] have questioned them, and J. Dodds [13] and E.R. Hoffman [14] (among others) have jointly analysed them. Many of those studies have focused on the transmission of Islamic elements to Christian buildings at an architectural and ornamental level, while the study of the transfer of figurative and iconographic elements has received much less attention. Even though several works have demonstrated the artistic permeability of Spanish Romanesque, many questions remain unstudied, and these interactions are still not widely assumed by historiography.

The borders between Al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms were both changeable and permeable, allowing for the constant circulation of people, ideas, and artistic objects. Some ivory pyxides and caskets made between the middle of the 10th century and the middle of the 11th in the workshops of Al-Andalus found their way to the Christian kingdoms a few decades later. The dissolution of the caliphate and subsequent instability, as well as the conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI in 1085, led to the dispersal of these objects. Many of them began to reach the Christian kingdoms from the second half of the 11th century on, where they were generally donated to ecclesiastic treasures and monastic ensembles.

These ivory items seem to have had a considerable artistic impact on Romanesque sculpture and monumental painting, which came into being precisely in the last third of the 11th century. Romanesque art presents various figurative motifs that appear earlier in Andalusi art, such as, for example, birds with intertwined necks, griffins and lions with curved tails, and some themes composed of human figures, such as musicians or equestrian falconers [15].

The transmission of motifs from Islamic to Romanesque art has not been the subject of a multidisciplinary analysis that addresses this issue as part of a broad process linked to the transfer of objects. It was proposed the need to undertake the joint analysis of both phenomena, both the transfer of figurative themes and that of sumptuary pieces from Al-Andalus to the Christian kingdoms. These objects conveyed a visual culture that would come to be shared by both communities, although with different connotations in each context.

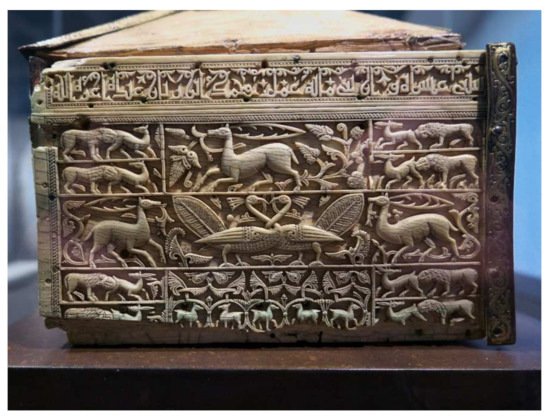

The casket made by Ibn Zayyan in the workshop of the Taifa of Cuenca in the year AD 1026 and preserved for centuries in the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos (currently in the Museo de Burgos) constitutes a paradigmatic example of this artistic phenomenon. An analysis of its function, its new meaning and influence on Christian visual culture offers relevant information for the study of the connections between Andalusi ivories and Romanesque sculpture, a field hardly explored until now.

2. The Iconographic Impact of the Silos Casket in Spanish Romanesque: The Christian Reception of Andalusi Visual Culture

It has been compared the whole of Ibn Zayyan’s casket iconography with Romanesque sculpture, noting that this small object had a surprising artistic influence. The most striking thing is that practically all the motifs that decorate its ivory plaques can be found in reliefs of churches and Romanesque cloisters scattered in an area that goes beyond the kingdoms of Castile and León.

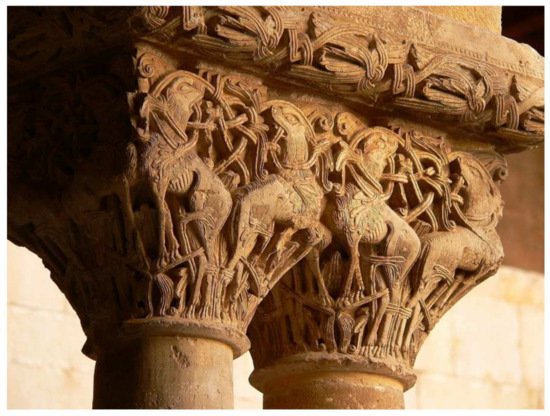

The casket seems to have an initial bearing on the lower cloister of the Silos monastery, whose capitals are deeply drilled with a notable stylistic influence from Andalusi ivories, as various scholars have already noticed ([16], p. 21) and [17]. Capital No. 6 in the east gallery (dated towards the first quarter of the 12th century) presents pairs of lions turning their backs and turning their heads backwards (Figure 1). The proportions of their heads, the disposition of their eyes and the incisions of their fur are very similar to those of the lions that form a cross with their bodies juxtaposed on the two broad faces of Ibn Zayyan’s casket (Figure 2), as already observed by Pérez de Urbel ([16], pp. 22–23). These lions are, however, trapped by vegetal tendrils in the capital within a Christian symbolic discourse. Boto has also found similarities between the griffins and quadrupeds in this piece and an illustration from the Beatus of Fernando I and Sancha (c. 1047), where fantastic animals appear with very similar curved tails, arranged in the same way, in a horizontal register.

Figure 1. Lions turning their backs on each other. Capital n° 6 from the East gallery of Santo Domingo de Silos cloister; first quarter of the 12th century. (Photo: Inés Monteira).

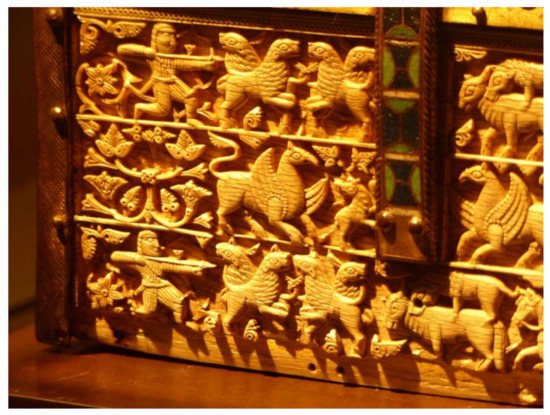

Figure 2. Archers, lions with juxtaposed bodies and lions attacking bulls on the front plaque of the casket from Santo Domingo de Silos, 1026, currently in the Museo de Burgos, Spain (Photo: Inés Monteira).

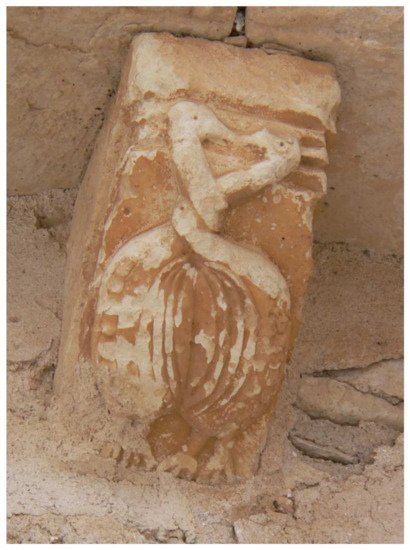

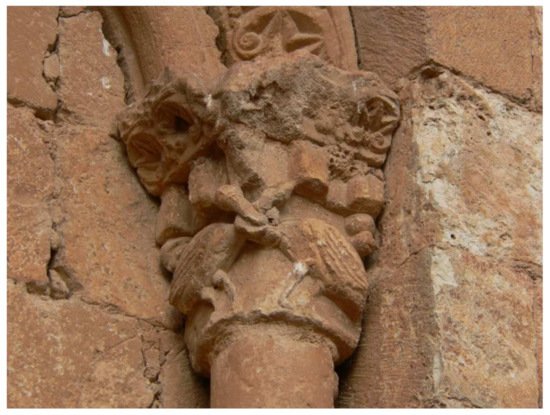

On the right-side plaque of the Silos casket, two affronted peacocks with intertwined necks can be observed (Figure 3). This is a recurring theme in the Andalusi carvings of the ‘Amirid period, and was found, for example, in the casket at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London from the early 11th century (inv. n° 10, 1866). This motif also has its parallels in some Romanesque examples, such as in a corbel in the church of Santa Marta del Cerro in Segovia, from the early 13th century, where the same pattern is adopted, although with a more heavy-handed carving and a different arrangement of the birds’ bodies, appearing vertically to conform to the shape of the corbel (Figure 4). The motif of a pair of birds intertwined by their necks appears in other Romanesque reliefs, such as on a capital form the church of San Miguel in San Esteban de Gormaz in Soria (Figure 5).

Figure 3. Ivory plaque with peacocks with intertwined necks, and lions with their heads seen from above. Right side of the casket from Santo Domingo de Silos, 1026, currently housed in the Museo de Burgos, Spain (Photo: Inés Monteira).

Figure 4. Corbel with birds with intertwined necks form the Romanesque church of Santa Marta del Cerro (Segovia), beginning of the 13th century. (Photo: Inés Monteira).

Figure 5. Birds with intertwined necks on a capital form the Romanesque church of San Miguel in San Esteban de Gormaz in Soria, c. 1081 (Photo: Inés Monteira).

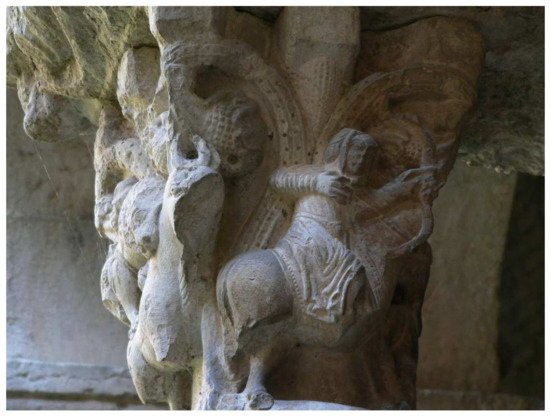

Flanking both sides of the peacocks on the Silos casket are lions biting the hinds of deer (Figure 3). These felines adopt a peculiar posture that is quite characteristic of Amirid and Taifa art, with their heads seen from above while their bodies appear in profile. This detail is incorporated in some early Romanesque examples, such as the capital of the San Salvador chapel in the Romanesque cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, as Walker already observed, built in the last quarter of the 11th century under the patronage of Alfonso VI ([18], p. 268). Other Romanesque reliefs include this peculiar posture, as can be seen in the lion attacking a quadruped in capital No. 4 of the cloister of the cathedral of Santa María de Girona (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Lion attacking a bull and Almoravid archer on capital n° 4 in the cloister of the cathedral of Santa Maria, Gerona (northwest face). (Photo: Inés Monteira).

Nevertheless, the outstanding motifs on the Silos casket are undoubtedly the archer and the figure of the lion attacking a bull, which appear four times on each of the main façades of the box (Figure 2). Although the conquering lion is a very frequent topic in Islamic art ([19], pp. 164–166), the peculiarity of this Andalusi piece lies in placing this motif next to the representation of an archer. The same combination of themes and figures can be found in capital No. 4 of the cloister of the cathedral of Girona (Figure 7) and in other examples of Catalan Romanesque [20]. The incorporation of the conquering lion in the capital of Girona is carried out, furthermore, with some formal features that seem to explicitly allude to Andalusi ivories, while the archers present clothing and ethnic features that identify them as Almoravid warriors (Figure 6 and Figure 7). All this leads to the conclusion that the sculptors of this capital borrowed these motifs from Islamic art seeking to paraphrase their original message, since they use them as an emblem of conquest over the territory, as I have been able to analyse in detail in a recent article ([20], pp. 491–497).

Figure 7. Almoravid archer with Negroid features and lion attacking a bull. Northeast face of capital n° 4 of the cloister of the Girona’s cathedral. (Photo: Inés Monteira).

Although the Girona capital is the sole example of a transfer from Andalusi art to Romanesque sculpture that has been known in its entire iconographic journey, the conclusions of this it cannot be extrapolated to others. It would be necessary to analyse the other motifs found in each Romanesque church to be able to interpret the degree of awareness that could exist regarding their Islamic origin and the intention with which they were introduced.

The widespread dissemination that the iconography of the Silos casket seems to have had, raises many questions, since it is unlikely that the sculptors of all these Romanesque buildings, scattered geographically and with a different chronology, would have been able to contemplate this ivory box, even though this monastery became an important pilgrimage site in the 12th century. Even more significant is the fact that the Santo Domingo de Silos monastery was one of the main centres of Iberian Christian artistic production throughout the 11th and 12th centuries, where there was an enamelling workshop, an active scriptorium and an outstanding monumental sculpture workshop. Some prominents of this time were produced in the Silos scriptorium, such as the Historia Silense (a chronicle of c.1118 focused on narrating the achievements of the struggle against Islam by Alfonso VI) and the Silos Beatus (1091–1109). It was also known that the capitals of this cloister had a major artistic influence throughout Castile and beyond [21]. Although it has generally been considered that it was the workers from the second Silos workshop (the ones dedicated to carving the capitals of the south and west galleries) who spread this style through the Iberian Romanesque, the means they used for it have not been known in depth. These sculptors, like the rest of the Romanesque artists, had to have model notebooks or some sort of support (parchment scrolls or tree bark), where the figurative prototypes that were to be transferred to the stone were traced. This would explain why the sculptural style of Silos was imitated in Castilian churches until the 13th century, which cannot be explained by a sole itinerant workshop transferring motifs from place to place. These notebooks were perishable, as they were instruments of daily one, meaning that few testimonies have been preserved. Thanks to them, the same figurative themes could be repeated in many buildings, and their existence may explain the enormous iconographic homogeneity that was found in Romanesque art, not only in the capitals but also in the corbels ([22], pp. 193–217). The model notebooks allowed the messages of the Gregorian Reform to reach the reliefs of all the churches, since there was a very rigid ecclesiastical supervision over the images that decorated the walls. This would lead us to believe that they were probably designed by learned clerics who devised the churches’ iconographic programmes, determining the images that should appear on their capitals, doorways, and corbels. Although the role of model books in Romanesque art has not yet received a systematic one due to the scarcity of preserved testimonies, there are substantial works on this question in relation to Gothic sculpture that demonstrate the significance that those sketches could have had for the design and execution of the reliefs in the later Middle Ages.

Considering the widespread dissemination of the sculpture of the Silos cloister, it can be presumed that some of these notebooks could have been made in its important scriptorium, allowing the propagation of its iconography throughout the surrounding area. The motifs that decorated Ibn Zayyan’s casket could also be copied in those notebooks or sketches that would have circulated throughout the Christian kingdoms, later being used on site by sculptors. Islamic textiles were undoubtedly an even more important element than ivories for the transmission of motifs from Islamic to Christian art since they were more abundant and easier to transport. However, it is unlikely that sculptors had such rich and fragile objects at their disposal at the time of carving the stone: there had to be an intermediate support. This modus operandi is the most plausible to explain the presence of composition schemes and figurative models that have generally been called “oriental” (Mesopotamian, Assyrian, Byzantine or Islamic) in many Romanesque buildings, as Baltrusiatis already noted in his 1934 work Art sumerien, art roman.

The transmission of the motifs of the Santo Domingo de Silos casket to Romanesque sculpture could also be explained by the existence of other similar Islamic objects that have now disappeared, as well as by the journey of Andalusi artists through the northern lands or the displacement of Christians to Al-Andalus ([18], pp. 259–275). Yet, in any case, it was necessary to have some sketches or drawings that would serve to plan the iconographic programmes and transfer them to stone. This would explain the diffusion of the same themes in such a wide geographic area and over such a long period, that went into the 13th century.

The problem of why it was desirable to introduce a series of motifs that were typical of Islamic art in the reliefs of Christian churches is even more important for explaining this phenomenon of figurative transmission. It has been already pointed out that this question can be answered by analysing the symbolism of each theme in each particular context. To this end, it is also important to know the Christian perceptions of Andalusi objects, the new function and the meaning that is given to them, as it was indicated in the previous section. The Arabic inscriptions that run through the ivory pieces from the 10th and 11th centuries reminded their new Christian owners that they belonged to Muslim leaders who had been defeated. Although the pieces could have arrived through trade, and not necessarily as war booty, they did so at a time of religious and territorial confrontation, as payment of parias or after the fitnah, the taking of Toledo or Cuenca. They were pieces appreciated for their aesthetic and material qualities, no doubt, but they were above all testimonies of the Christian victory, which led to their exhibition in sacred spaces.

References

- Werckmeister, O.K. The Islamic Rider in the Beatus of Girona. Gesta 1997, 36, 101–106.

- Stierlin, H. Le Livre de Feu. L´Apocalypse et l´art mozarabe; Sigma: Geneva, Switzerland, 1978.

- Williams, J. Los Beatos and the Reconquista. In Patrimonio Artístico de Galicia y Otros Estudios. Homenaje al Prof. Dr. Serafín Moralejo Álvarez; Dir. y Coord. Á. Franco Mata.; Xunta de Galicia: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2004; Volume 3, pp. 297–302.

- Klein, P. Im spannungsfeld von endzeitängsten, Konflikten mit dem Islam und liturgischer praxis: Die erneuerung der Beatus-illustration. In Vervuert–Iberoamericana: Cruce de Culturas, Arquitectura y su Decoración en la Península Ibérica del Siglo VI a X/XI; Vervuert – Iberoamericana: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2016.

- Zozaya, J. Interacción islamo-cristiana en el siglo X: El retrato del fº 134rv del Beato de Gerona. In Mundos Medievales: Espacios, Sociedades y Poder: Homenaje al Profesor José Ángel García de Cortázar y Ruiz de Aguirre; Editorial de la Universidad de Cantabria: Cantabria, Spain, 2012; Volume 1, pp. 927–938.

- Shalem, A. Islam Christianized. Islamic Portable Objects in the Medieval Church Treasures of the Latin West; Peter Lang: Frankfurt, Germany, 1998.

- Rosser-Owen, M. Islamic Objects in Christian Contexts: Relic Translation and Modes of Transfer in Medieval Iberia. Art Transl. 2015, 7, 39–63.

- Lambert, É. Art Musulman et Art Chrétien dans la Péninsule Ibérique. Privat: Paris-Toulouse, France, 1956.

- Mâle, É. Les influences arabes dans l’art roman. Revue des Deux Mondes 1923, 2, 311–343.

- Fikry, A. L’Art roman du Puy et les influences islamiques . (PhD Thesis presented in Paris, 1934), E. Leroux, Paris, France, 1974.

- Watson, K. French Romanesque and Islam: Andalusian Elements in French Architectural Decoration c.1030–1180; BAR International Series: Oxford, UK, 1989.

- Barral i Altet, X. Sur les supposées influences islamiques dans l’art roman: L’exemple de la cathédrale Notre-Dame du Puy-en-Velay. Cahiers de Saint-Michel de Cuxa 2004, 35, 115–118.

- Dodds, J.D. Islam, Christianity, and the Problem of Religious Art. In The Art of Medieval Spain. AD 500–1200; The Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 27–37.

- Hoffman, E.R. Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century. Art Hist. 2001, 24, 17–50.

- Dodds, J.D. Algunas reflexiones acerca de las pinturas bajas de San Baudelio de Berlanga. In Pintado en la Pared: El Muro Como Soporte Visual en la Edad Media; Manzarbeitia Valle, S., Azcárate Luxán, M., González Hernandez, I., Eds.; Ediciones Complutense: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 97–120.

- Pérez De Urbel, J. El Claustro de Silos; Institución Fernán González: Burgos, Spain, 1975.

- Senra Gabriel y Galán, J.L. El monasterio de Santo Domingo de Silos y la secuencia temporal de una singular arquitectura ornamentada. In Siete Maravillas del Románico Español; Pedro, L.H., Ed.; Fundación Santa María la Real: Aguilar de Campoo, Spain, 2009; pp. 193–225.

- Walker, R. Sculptors in Medieval Spain following the 1085 Fall of Toledo. In Romanesque and the Mediterranean: Points of Contact across the Latin, Greek and Islamic Worlds c.1000 to c.1250; Bacile, R., Mc Neil, J., Eds.; Maney Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2015; pp. 259–275.

- Hartner, W.; Ettinghausen, R. The Conquering Lion, the Life Cycle of a Symbol. Oriens 1964, 17, 161.

- Monteira, I. Of Archers and Lions: The Capital of the Islamic Rider in the Cloister of Girona Cathedral. Medieval Encount. 2019, 25, 457–498.

- Lozano López, E. Maestros castellanos del entorno del segundo taller silense: Repertorios figurativos y soluciones estilísticas. In Neue Forschungen zur Bauskulptur in Frankreich und Spanien im Spannungsfeldt des Portail Royal in Chartres und des Portico de la Gloria in Santiago de Compostela. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin-Kunstgeschichtliches Seminar; Vervuert Verlag: Berlin/Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2010; pp. 197–211.

- Monteira, I. El Enemigo Imaginado. La Escultura Románica Hispana y la Lucha Contra el Islam; Méridiennes-CNRS: Toulouse, France, 2012.

More

Information

Subjects:

History

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

02 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No