You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by INÉS MONTEIRA and Version 3 by Amina Yu.

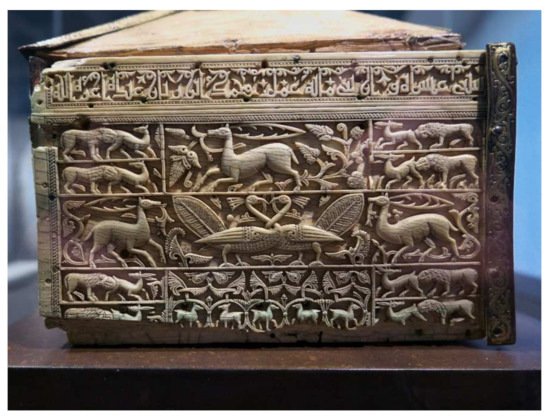

The ivory casket made in Cuenca in A.D. 1026 and signed by Mohammad ibn Zayyan constitutes invaluable evidence for the study of artistic transfers between Al-Andalus and the Iberian Christian kingdoms. In the 12th century this piece was transformed in the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos (Burgos) with the addition of Christian-themed enamels and reused as a reliquary.

- Islamic motifs in Spanish Romanesque

- Ibn Zayyan ivory casket

- monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos

1. Introduction: Transfers between Andalusi Art and the Spanish Romanesque

Iberian art from the 10th to the 12th centuries has been the subject of countless studies from the 19th century on due to its extraordinary richness and uniqueness. Nevertheless, a disciplinary barrier has long been present leading to the separation of Christian art from Islamic art of this period, thus converting them into two independent specialties. The border that once existed between Al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms seems to have led, to some extent, to the separate study of their respective artistic manifestations, despite their geographic and chronological proximity, and their clear connections. There are, however, significant studies about those artistic contacts, primarily in Mozarabic architecture and the illustrated Beatus commentaries. Scholars such as O.K. Werckmeister [1], H. Stierlin [2], J. Williams [3], and P. Klein [4] have analysed these interchanges. Others such as J. Zozaya [5], A. Shalem [6] and M. Rosser-Owen [7] have addressed the importance of Andalusi artworks in the Christian north. In regard to Romanesque art of the 11th and 12th centuries, these connections have been approached from multiple points of view. Scholars like É. Lambert [8], É. Mâle [9], A. Fikry [10] and K. Watson [11] have reaffirmed them, while others like X. Barral i Altet [12] have questioned them, and J. Dodds [13] and E.R. Hoffman [14] (among others) have jointly analysed them. Many of those studies have focused on the transmission of Islamic elements to Christian buildings at an architectural and ornamental level, while the study of the transfer of figurative and iconographic elements has received much less attention. Even though several works have demonstrated the artistic permeability of Spanish Romanesque, many questions remain unstudied, and these interactions are still not widely assumed by historiography.

The borders between Al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms were both changeable and permeable, allowing for the constant circulation of people, ideas, and artistic objects. Some ivory pyxides and caskets made between the middle of the 10th century and the middle of the 11th in the workshops of Al-Andalus found their way to the Christian kingdoms a few decades later1. The dissolution of the caliphate and subsequent instability, as well as the conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI in 1085, led to the dispersal of these objects2. Many of them began to reach the Christian kingdoms from the second half of the 11th century on, where they were generally donated to ecclesiastic treasures and monastic ensembles.

These ivory items seem to have had a considerable artistic impact on Romanesque sculpture and monumental painting, which came into being precisely in the last third of the 11th century. Romanesque art presents various figurative motifs that appear earlier in Andalusi art, such as, for example, birds with intertwined necks, griffins and lions with curved tails, and some themes composed of human figures, such as musicians3 or equestrian falconers [15].

The transmission of motifs from Islamic to Romanesque art has not been the subject of a multidisciplinary analysis that addresses this issue as part of a broad process linked to the transfer of objects4. In t washis article, we proposed the need to undertake the joint analysis of both phenomena, both the transfer of figurative themes and that of sumptuary pieces from Al-Andalus to the Christian kingdoms. These objects conveyed a visual culture that would come to be shared by both communities, although with different connotations in each context.

The casket made by Ibn Zayyan in the workshop of the Taifa of Cuenca in the year AD 1026 and preserved for centuries in the monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos (currently in the Museo de Burgos) constitutes a paradigmatic example of this artistic phenomenon. An analysis of its function, its new meaning and influence on Christian visual culture offers relevant information for the study of the connections between Andalusi ivories and Romanesque sculpture, a field hardly explored until now.

2. The Iconographic Impact of the Silos Casket in Spanish Romanesque: The Christian Reception of Andalusi Visual Culture

IAlt has beenhough few works have compared the whole of Ibn Zayyan’s casket iconography with Romanesque sculpture, notingwe note that this small object had a surprising artistic influence. The most striking thing is that practically all the motifs that decorate its ivory plaques can be found in reliefs of churches and Romanesque cloisters scattered in an area that goes beyond the kingdoms of Castile and León. The casket seems to have an initial bearing on the lower cloister of the Silos monastery, whose capitals are deeply drilled with a notable stylistic influence from Andalusi ivories, as various scholars have already noticed ([16][28], p. 21) and [17][29]. Capital No. 6 in the east gallery (dated towards the first quarter of the 12th century7) presents pairs of lions turning their backs and turning their heads backwards (Figure 13). The proportions of their heads, the disposition of their eyes and the incisions of their fur are very similar to those of the lions that form a cross with their bodies juxtaposed on the two broad faces of Ibn Zayyan’s casket (Figure 24), as already observed by Pérez de Urbel ([16][28], pp. 22–23)8. These lions are, however, trapped by vegetal tendrils in the capital within a Christian symbolic discourse. Boto has also found similarities between the griffins and quadrupeds in this piece and an illustration from the Beatus of Fernando I and Sancha (c. 1047), where fantastic animals appear with very similar curved tails, arranged in the same way, in a horizontal register9.

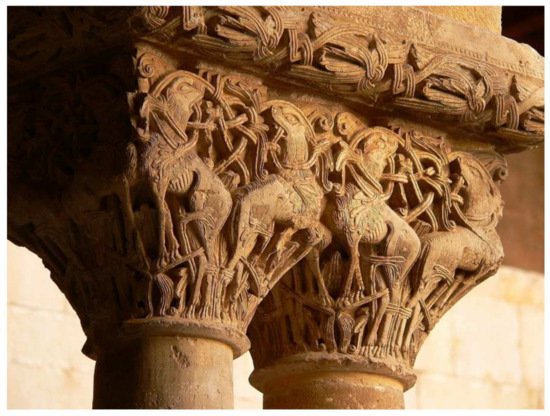

Figure 13. Lions turning their backs on each other. Capital n° 6 from the East gallery of Santo Domingo de Silos cloister; first quarter of the 12th century. (Photo: Inés Monteira).

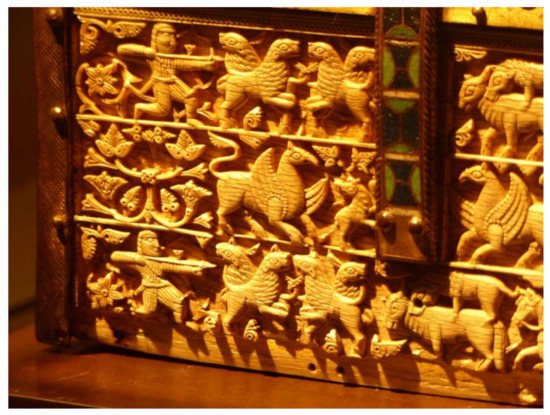

Figure 24. Archers, lions with juxtaposed bodies and lions attacking bulls on the front plaque of the casket from Santo Domingo de Silos, 1026, currently in the Museo de Burgos, Spain (Photo: Inés Monteira).

Figure 35. Ivory plaque with peacocks with intertwined necks, and lions with their heads seen from above. Right side of the casket from Santo Domingo de Silos, 1026, currently housed in the Museo de Burgos, Spain (Photo: Inés Monteira).

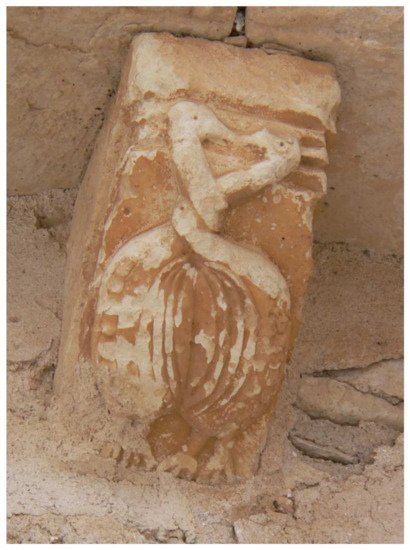

Figure 46. Corbel with birds with intertwined necks form the Romanesque church of Santa Marta del Cerro (Segovia), beginning of the 13th century. (Photo: Inés Monteira).

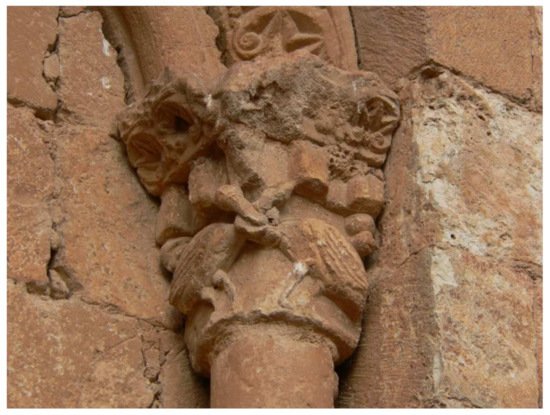

Figure 57. Birds with intertwined necks on a capital form the Romanesque church of San Miguel in San Esteban de Gormaz in Soria, c. 1081 (Photo: Inés Monteira).

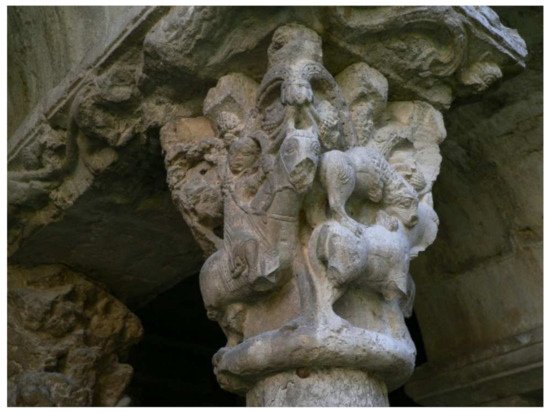

Figure 68. Lion attacking a bull and Almoravid archer on capital n° 4 in the cloister of the cathedral of Santa Maria, Gerona (northwest face). (Photo: Inés Monteira).

Figure 79. Almoravid archer with Negroid features and lion attacking a bull. Northeast face of capital n° 4 of the cloister of the Girona’s cathedral. (Photo: Inés Monteira).