| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Giulia Tarquini | + 3172 word(s) | 3172 | 2022-03-15 09:11:46 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -135 word(s) | 3037 | 2022-03-25 03:42:49 | | | | |

| 3 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3037 | 2022-03-25 04:09:15 | | | | |

| 4 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3037 | 2022-03-25 04:10:15 | | | | |

| 5 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 3037 | 2022-03-25 04:11:31 | | |

Video Upload Options

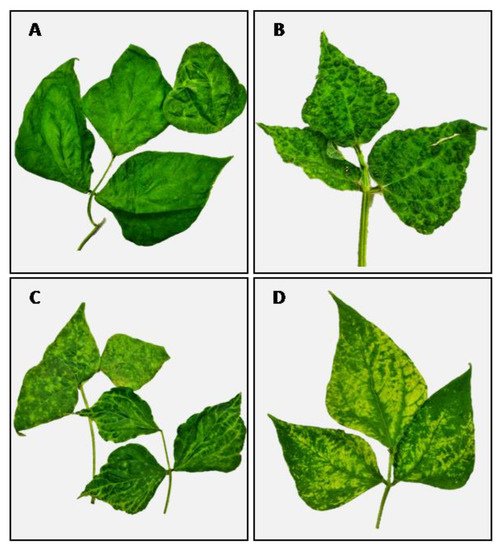

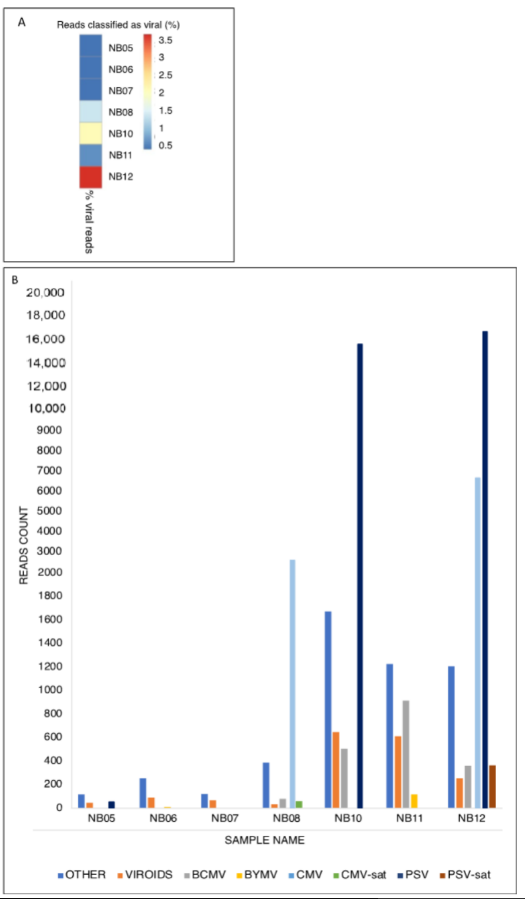

‘Lamon bean’ is a protected geographical indication (PGI) for a product of four varieties of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) grown in a specific area of production, which is located in the Belluno district, Veneto region (N.E. of Italy). The ‘Lamon bean’ has been threatened by severe virus epidemics that have compromised its profitability. The full virome of seven bean samples showing different foliar symptoms was obtained by MinION sequencing. Evidence that emerged from sequencing was validated through RT-PCR and ELISA in a large number of plants, including different ecotypes of Lamon bean and wild herbaceous hosts that may represent a virus reservoir in the field. Results revealed the presence of bean common mosaic virus (BCMV), cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), peanut stunt virus (PSV), and bean yellow mosaic virus (BYMV), which often occurred as mixed infections. Moreover, both CMV and PSV were reported in association with strain-specific satellite RNAs (satRNAs).

1. Introduction

Considering the wide diversity of species and viral strains that could be detected in Lamon bean, a fully comprehensive and sensitive diagnostic tool, able to explore such a great variability, was highly needed.

For this reason, researchers took advantage of the advent of High Throughput Sequencing (HTS) approaches, which in the last two decades have allowed great advances and have promoted discovery, diagnostics, and evolutionary studies [3]. Plant virus research has been heavily impacted by the development of HTS techniques for the identification of emerging viruses, genome reconstruction, analysis of population structures, evolution of novel viral strain(s), and much more [4][5][6][7][8][9]. Single-molecule sequencing technologies, often called “third generation sequencing”, provide greater advantages over second-generation approaches, including the production of long read lengths that are easier to map to a reference sequence and that facilitate de novo assembly, short run times, small amounts of input nucleic acids (DNA or RNA), and low cost for a single run [3]. The consistent improvement in HTS technologies has occurred in parallel with the continuous development of suitable bioinformatic tools for data analysis and with the online availability of a wide range of biological data sets, which have allowed a deeper comprehension of HTS results [6][7].

In this entry, a third-generation sequencing platform, namely MinION, provided by Oxford Nanopore Technologies, was exploited to obtain the virome of seven bean samples that exhibited different foliar symptoms resembling those of virus disease. The picture that emerged from the sequencing results was consolidated through RT-PCR and ELISA assays in many samples, inclusive of different varieties of bean grown in the Lamon area and various families of herbaceous plants, which may represent a virus reservoir in the field.

2. Virome Determination

3. RT-PCR and ELISA Detection

A total of 59 samples were tested by RT-PCR assays to confirm the presence of the viruses detected by MinION sequencing, BCMV, CMV, PSV and BYMV (Table 1). Three Lamon beans were negative to all tested viruses (9%). Single infections caused by BCMV, and PSV were detected in 39% and 13% of Lamon beans, respectively, while CMV was reported in 21% of bean samples, exclusively in co-presence with either BCMV (9%), PSV (3%), or both (9%). Mixed infection by BCMV and PSV was also reported in 12% of Lamon beans. BYMV was identified, exclusively by MinION sequencing, in two samples (6%) either as a single infection (LB-21, NB06) or in co-presence with BCMV (LB-4, NB11). All herbaceous hosts were negative for the presence of BCMV. CMV was exclusively reported in Trifolium pratense L. (Leguminosae), both as a single infection (4%) and in co-presence with PSV (8%). Single infection caused by PSV was detected in Trifolium pratense L. (8%), Chrysanthemum sp. (4%) and, for the first time, in Solanum tuberosum L. (8%). Members of the Amaranthaceae (Chenopodium album L., Amaranthus retroflexus L., and Achillea millefolium L.), Apiaceae (Daucus carota L.), and Asteraceae (Taraxacum officinale L.) were negative to all tested viruses (68%). The results of ELISA tests are reported in Table 2 and revealed BCMV presence in samples collected in all the surveyed municipalities, with an incidence ranging from 40% to 100%. CMV was serologically identified in 50% and 62% of the samples belonging to the two municipalities (Sovramonte and Belluno) with incidence of 25 and 30%, respectively.

4. BLAST Analysis of Sanger Sequences and Phylogenetic Investigation

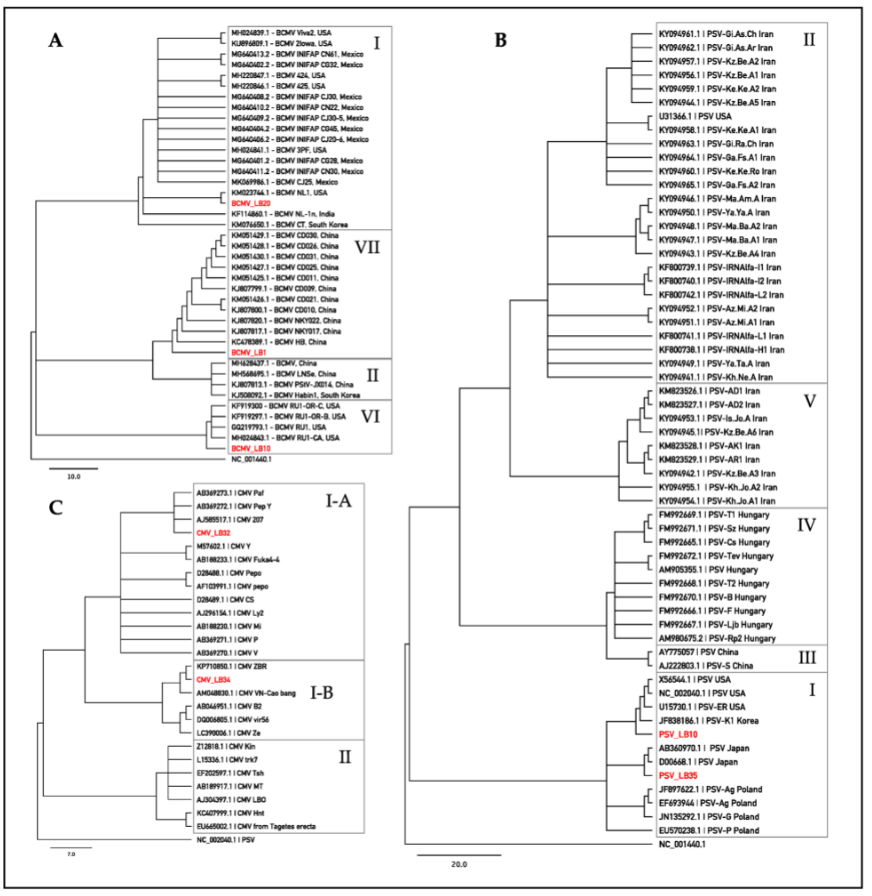

Sequences obtained by Sanger were used for assignment to pathotypes/subgroups according to recent comprehensive studies of BCMV [10], CMV [11], and PSV [12]. The results revealed that 79% of BCMV sequences fall into pathotype VII, sharing 97.7–99.2% identity with NL-4 strain (DQ666332) [13]. Three BCMV sequences (13%) were included in the pathotype I, exhibiting from 99.0% to 99.6% of sequence similarity to the NL-1 strain (KM023744) [14]. The remaining BCMV sequences (8%) fall into pathotype VI, sharing 95.6–99.2% identity with recombinant RU-1 (GQ219793) [15] and RU-1-CA (MH024843) [16] strains. All PSV sequences belonged to subgroup IA, showing a sequence similarity that ranged from 92.7% to 99.3% with the PSV-ER strain (U15730) [17]. CMV sequences can be assigned to the subgroups IA and IB, exhibiting 99.3% identity with Fny-CMV strain (D10538) and 95.3–96.4% sequence similarity with As-CMV strain (AF013291), respectively [18][19][20]. Results of BLAST analyses are summarized in Table 3. Phylogenetic analyses (Figure 3) assigned reference sequences of the isolates of BCMV, PSV and CMV detected in Lamon bean plants to the respective clusters congruently with the BLAST results outlined above. The phylogenetic analysis carried out with the introduction of other sequence variants found in the survey produced similar results (not shown).

5. Discussion

An all-encompassing description of the virome associated with a crop and the availability of high-throughput diagnostic tools are useful to improve viral disease control strategies. The continuous development of newer and even more robust and user-friendly High Throughput Sequencing (HTS) technologies for detecting and identifying viruses makes these new approaches suitable for routine use in testing laboratories, representing a powerful new high-throughput diagnostic tool [3][21].

References

- Rojas, M.R.; Gilbertson, R.L. Emerging plant viruses: A diversity of mechanisms and opportunities. In Plant Virus Evolution; Roossinck, M.J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 27–51. ISBN 978-3-540-75763-4.

- Lecoq, H.; Moury, B.; Desbiez, C.; Palloix, A.; Pitrat, M. Durable virus resistance in plants through conventional approaches: A challenge. Virus Res. 2004, 100, 31–39.

- Chalupowicz, L.; Dombrovsky, A.; Gaba, V.; Luria, N.; Reuven, M.; Beerman, A.; Lachman, O.; Dror, O.; Nissan, G.; Manulis-Sasson, S. Diagnosis of plant diseases using the Nanopore sequencing platform. Plant Pathol. 2018, 68, 229–238.

- Adams, I.P.; Glover, R.H.; Monger, W.A.; Mumford, R.; Jackeviciene, E.; Navalinskiene, M.; Samuitiene, M.; Boonham, N. Next-generation sequencing and metagenomic analysis: A universal diagnostic tool in plant virology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2009, 10, 537–545.

- Al Rwahnih, M.; Daubert, S.; Golino, D.; Islas, C.; Rowhani, A. Comparison of Next-Generation Sequencing Versus Biological Indexing for the Optimal Detection of Viral Pathogens in Grapevine. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 758–763.

- Wu, Q.; Ding, S.-W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, S. Identification of Viruses and Viroids by Next-Generation Sequencing and Homology-Dependent and Homology-Independent Algorithms. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2015, 53, 425–444.

- Roossinck, M.J. Deep sequencing for discovery and evolutionary analysis of plant viruses. Virus Res. 2017, 239, 82–86.

- Jo, Y.; Choi, H.; Kim, S.-M.; Kim, S.-L.; Lee, B.C.; Cho, W.K. The pepper virome: Natural co-infection of diverse viruses and their quasispecies. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 453.

- Czotter, N.; Molnar, J.; Szabó, E.; Demian, E.; Kontra, L.; Baksa, I.; Szittya, G.; Kocsis, L.; Deák, T.; Bisztray, G.; et al. NGS of Virus-Derived Small RNAs as a Diagnostic Method Used to Determine Viromes of Hungarian Vineyards. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 122.

- Abadkhah, M.; Hajizadeh, M.; Koolivand, D. Global population genetic structure ofBean common mosaic virus. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2020, 53, 266–281.

- Wang, D.F.; Wang, J.R.; Cui, L.Y.; Wang, S.T.; Niu, Y. Molecular identification and phylogeny of cucumber mosaic virus and zucchini yellow mosaic virus co-infecting Luffa cylindrica L. in Shanxi, China. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 477–487.

- Amid-Motlagh, M.H.; Massumi, H.; Heydarnejad, J.; Mehrvar, M.; Hajimorad, M.R. Nucleotide sequence analyses of coat protein gene of peanut stunt virus isolates from alfalfa and different hosts show a new tentative subgroup from Iran. Virus Dis. 2017, 28, 295–302.

- Bravo, E.; Calvert, L.A.; Morales, F.J. The complete nucleotide sequence of the genomic RNA of Bean common mosaic virus strain NL4. Genetica 2008, 32, 37–46.

- Martin, K.; Hill, J.H.; Cannon, S. Occurrence and Characterization of Bean common mosaic virus Strain NL1 in Iowa. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 1593.

- Feng, X.; Poplawsky, A.R.; Nikolaeva, O.V.; Myers, J.R.; Karasev, A. Recombinants of Bean common mosaic virus (BCMV) and Genetic Determinants of BCMV Involved in Overcoming Resistance in Common Bean. Phytopathology 2014, 104, 786–793.

- Feng, X.; Orellana, G.E.; Myers, J.R.; Karasev, A.V. Recessive Resistance to Bean common mosaic virus Conferred by the bc-1 and bc-2 Genes in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Affects Long-Distance Movement of the Virus. Phytopathology 2018, 108, 1011–1018.

- Hu, C.C.; Naidu, R.A.; Aboul-Ata, A.E.; Ghabrial, S.A. Evidence for the occurrence of two distinct subgroups of peanut stunt cucumovirus strains: Molecular characterization of RNA3. J. Gen. Virol. 1997, 78, 929–939.

- Roossinck, M.J.; Zhang, L.; Hellwald, K.-H. Rearrangements in the 5 J Nontranslated Region and Phylogenetic Analyses of Cucumber Mosaic Virus RNA 3 Indicate Radial Evolution of Three Subgroups. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 7.

- Fraile, A.; Alonso-Prados, J.L.; Aranda, M.A.; Bernal, J.J.; Malpica, J.M.; García-Arenal, F. Genetic exchange by recombination or reassortment is infrequent in natural populations of a tripartite RNA plant virus. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 934–940.

- Roossinck, M.J. Evolutionary History of Cucumber Mosaic Virus Deduced by Phylogenetic Analyses. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3382–3387.

- Pooggin, M.M. Small RNA-Omics for Plant Virus Identification, Virome Reconstruction, and Antiviral Defense Characterization. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2779.

- Wang, Y.; Gaba, V.; Yang, J.; Palukaitis, P.; Gal-On, A. Characterization of Synergy Between Cucumber mosaic virus and Potyviruses in Cucurbit Hosts. Phytopathology 2002, 92, 51–58.

- Chiquito-Almanza, E.; Acosta-Gallegos, J.A.; García-Álvarez, N.C.; Garrido-Ramírez, E.R.; Montero-Tavera, V.; Guevara-Olvera, L.; Anaya-López, J.L. Simultaneous Detection of both RNA and DNA Viruses Infecting Dry Bean and Occurrence of Mixed Infections by BGYMV, BCMV and BCMNV in the Central-West Region of Mexico. Viruses 2017, 9, 63.

- Moreno, A.B.; Lopez-Moya, J.J. When viruses play team sports: Mixed infections in plants. Phytopathology 2020, 110, 29–48.

- Minicka, J.; Zarzyńska-Nowak, A.; Budzyńska, D.; Borodynko-Filas, N.; Hasiów-Jaroszewska, B. High-Throughput Sequencing Facilitates Discovery of New Plant Viruses in Poland. Plants 2020, 9, 820.

- Singh, S.P.; Schwartz, H.F. Breeding Common Bean for Resistance to Diseases: A Review. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, 2199–2223.

- Bonnet, J.; Fraile, A.; Sacristán, S.; Malpica, J.M.; García-Arenal, F. Role of recombination in the evolution of natural populations of Cucumber mosaic virus, a tripartite RNA plant virus. Virology 2005, 332, 359–368.

- Hu, C.-C.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Lin, N.-S. Satellite RNAs and Satellite Viruses of Plants. Viruses 2009, 1, 1325–1350.

- Collmer, C.W.; Howell, S.H. Role of Satellite RNA in the Expression of Symptoms Caused by Plant Viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1992, 30, 419–442.

- Kaper, J.; Tousignant, M. Cucumber Mosaic Virus-Associated RNA 5: I. Role of Host Plant and Helper Strain in Determining Amount of Associated RNA 5 with Virions. Virology 1977, 80, 186–195.

- Kaper, J.; Collmer, C. Modulation of Viral Plant Diseases by Secondary RNA Agents. In RNA Genetics; Volume III. Variability of RNA Genomes; CRC Press Inc.: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1988; pp. 171–194.

- Kaper, J. Rapid synthesis of double-stranded cucumber mosaic virus-associated RNA 5: Mechanism controlling viral pathogenesis? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1982, 105, 1014–1022.

- García-Arenal, F.; Palukaitis, P. Structure and Functional Relationships of Satellite RNAs of Cucumber Mosaic Virus. Protein Secret. Export. Bact. 1999, 239, 37–63.

- Kouadio, K.T.; De Clerck, C.; Agneroh, T.A.; Parisi, O.; Lepoivre, P.; Jijakli, H. Role of Satellite RNAs in Cucumber Mosaic Virus-Host Plant Interactions: A Review. Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2013, 17, 644–650.

- Garcia-Arenal, F.; Zaitlin, M.; Palukaitis, P. Nucleotide sequence analysis of six satellite RNAs of cucumber mosaic virus: Primary sequence and secondary structure alterations do not correlate with differences in pathogenicity. Virology 1987, 158, 339–347.

- Moriones, E.; Diaz, I.; Rodriguez-Cerezo, E.; Fraile, A.; Garcia-Arenal, F. Differential interactions among strains of tomato aspermy virus and satellite RNAs of cucumber mosaic virus. Virology 1992, 186, 475–480.

- Fisher, J.R. Identification of Three Distinct Classes of Satellite RNAs Associated with Two Cucumber mosaic virus Serotypes from the Ornamental Groundcover Vinca minor. Plant Health Prog. 2012, 13, 18.

- Ferreiro, C.; Ostrówka, K.; Lopez-Moya, J.J.; Díaz-Ruíz, J.R. Nucleotide sequence and symptom modulating analysis of a Peanut stunt virus-associated satellite RNA from Poland: High level of sequence identity with the American PSV satellites. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1996, 102, 779–786.

- Militão, V.; Rodríguez-Cerezo, E.; Moreno, I.; Garcia-Arenal, F. Differential interactions among isolates of peanut stunt cucumovirus and its satellite RNA. J. Gen. Virol. 1998, 79, 177–184.

- Obrępalska-Stęplowska, A.; Wieczorek, P.; Budziszewska, M.; Jeszke, A.; Renaut, J. How can plant virus satellite RNAs alter the effects of plant virus infection? A study of the changes in the Nicotiana benthamiana proteome after infection by Peanut stunt virus in the presence or absence of its satellite RNA. Proteomics 2013, 13, 2162–2175.

- Uga, H.; Tsuda, S. A One-Step Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction System for the Simultaneous Detection and Identification of Multiple Tospovirus Infections. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 166–171.

- Van Dijk, E.L.; Jaszczyszyn, Y.; Naquin, D.; Thermes, C. The Third Revolution in Sequencing Technology. Trends Genet. 2018, 34, 666–681.

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Holt, K.E. Performance of neural network basecalling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 1–10.

- Pruss, G.; Ge, X.; Shi, X.M.; Carrington, J.; Vance, V.B. Plant viral synergism: The potyviral genome encodes a broad-range pathogenicity enhancer that transactivates replication of heterologous viruses. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 859–868.

- Syller, J.; Grupa, A. Antagonistic within-host interactions between plant viruses: Molecular basis and impact on viral and host fitness: Antagonistic Interactions between Plant Viruses. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 769–782.