Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guillermo Ahumada | + 4056 word(s) | 4056 | 2022-03-21 04:53:01 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | -95 word(s) | 3961 | 2022-03-22 04:39:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ahumada, G. Fluorescent Polymers Conspectus. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20783 (accessed on 13 March 2026).

Ahumada G. Fluorescent Polymers Conspectus. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20783. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Ahumada, Guillermo. "Fluorescent Polymers Conspectus" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20783 (accessed March 13, 2026).

Ahumada, G. (2022, March 21). Fluorescent Polymers Conspectus. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20783

Ahumada, Guillermo. "Fluorescent Polymers Conspectus." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

The development of luminescent materials is critical to humankind. The Nobel Prizes awarded in 2008 and 2010 for research on the development of green fluorescent proteins and super-resolved fluorescence imaging are proof of this (2014). Fluorescent probes, smart polymer machines, fluorescent chemosensors, fluorescence molecular thermometers, fluorescent imaging, drug delivery carriers, and other applications make fluorescent polymers (FPs) exciting materials.

fluorescent polymers

aie fluorescent polymers

1. Introduction

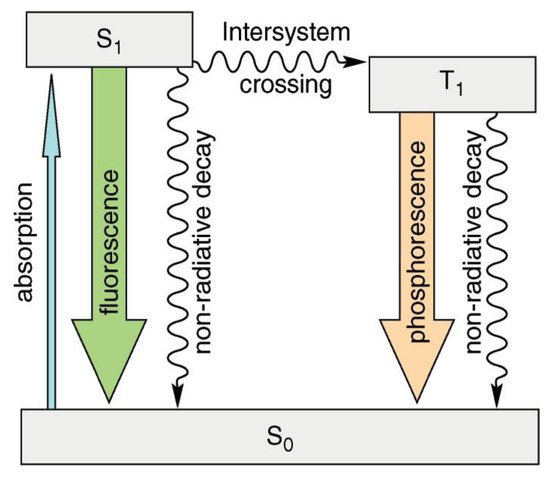

Luminescence is the emission of visible, ultraviolet, or infrared light in the optical range that is an excess over the thermal radiation emitted by the substance at a given temperature and continues after absorbing the excitation energy for a time significantly longer than the period of the absorbed light [1]. Various types of luminescence can be identified (e.g., hemi-, bio-, tribo-, and thermo-luminescence). Photoluminescence occurs when molecules interact with photons of electromagnetic radiation. Fluorescence occurs when electromagnetic energy is instantaneously released from the singlet state [2]. Some compounds display delayed fluorescence, which may be mistaken for phosphorescence. This is the outcome of two intersystem crossings, one from the singlet to the triplet and one from the triplet back to the singlet (Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1. Simplified diagram (Perrin–Jablonski) showing the difference between fluorescence and phosphorescence.

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines fluorescence (for organic molecules) as the spontaneous emission of radiation (luminescence) from an excited molecular entity with spin multiplicity retention [4]. This definition becomes irrelevant in species such as nanocrystalline semiconductors (quantum dots or fluorescent quantum dots) [5] or metallic nanoparticles (fluorescent gold nanoparticles) [6] due to their complex emission processes.

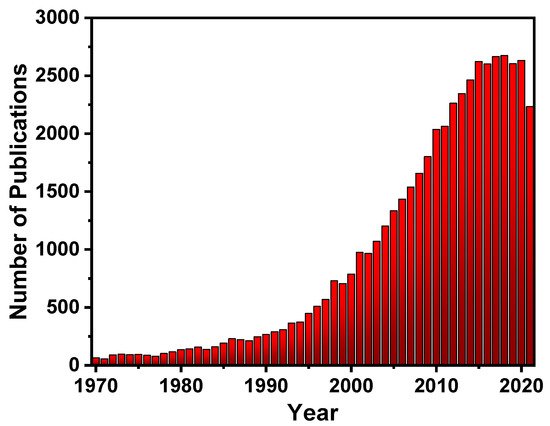

Fluorescent materials have been in high demand over the last decade [7], and to meet this demand, a large number of substances with fluorescent properties have been explored, such as silica particles [8], glass [9], gold surfaces [10], quantum dots [11], and carbon dots [12], which are combined with a variety of chemical receptors to produce a variety of fluorescent materials. Because of this high demand, there has been a lot of interest in fluorescent polymers (FPs)research (Figure 2), due to their fascinating properties such as their increased signal response even after disturbance due to cooperative conformational effects of its chain segments. This is especially advantageous due to its superior visco-elastic and mechanical properties, which aid in the manufacturing of new devices [13][14][15][16][17][18]. FPs, similar to small fluorescent molecules, have a wide range of uses for sensing [19][20] and imaging [21][22][23][24][25][26], optoelectronics [27], fluorescent bioprobes [28], molecular imaging [29], photodynamic treatments [30], OLEDs [31], storage data security [32], encryption [33], anti-counterfeiting materials [34], and other fields [26][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42].

Figure 2. The number of publications per year on (FPs).

Based on the strategies for developing these materials, two major branches can be distinguished in the field of FPs: (1) the use of a polymer chain (in general, using a conducting polymer) containing fluorophores [43][44][45][46][47], and (2) the burgeoning field of aggregation-induced emission (AIE) polymers [48][49][50][51][52][53]. Traditionally, conjugated polymers (CPs) have been employed as primary FPs [54][55], where the electronic conjugation between each repeating unit creates a semiconductive ‘‘molecular wire’’, providing very useful optical and electronic properties. However, the usage of non-conjugated polymers (NCPs) to create FPs has steadily gained popularity. This advancement was substantially aided by advances in controlled polymerizations of NCPs, which gave unprecedented control over polymer compositions and topologies [56][57].

In comparison with traditional FPs, AIE polymers present the advantages of high PL efficiency in aggregate and solid states, a large Stokes shift, outstanding photostability, etc. Thus, AIE polymers are expected to exhibit unique properties and remarkable advantages in their practical applications [50][58][59]. Furthermore, the structure, composition, and morphology of AIE polymers can be fine-tuned to meet the diverse needs of practical applications in chemo/biosensing, imaging, and theranostics.

2. Polymers Containing Fluorophores

2.1. Non-Conjugated Polymers Containing Fluorophores

Polymers are important and ubiquitous in modern society. They are widely used in housewares, packaging, coatings, biomedical supplies, textiles and fabrics, adhesives, engineering composites, and other applications due to their ease of processing and wide range of mechanical performances [60][61][62][63]. Polymers and polymer-based composites are designed and manufactured to be as robust as possible to meet the requirements of most engineering applications. Several examples in the literature can be found in the preparation of functional non-conjugated FPs by chemically customizing the core chromophore and the macromolecular assembly strategy.

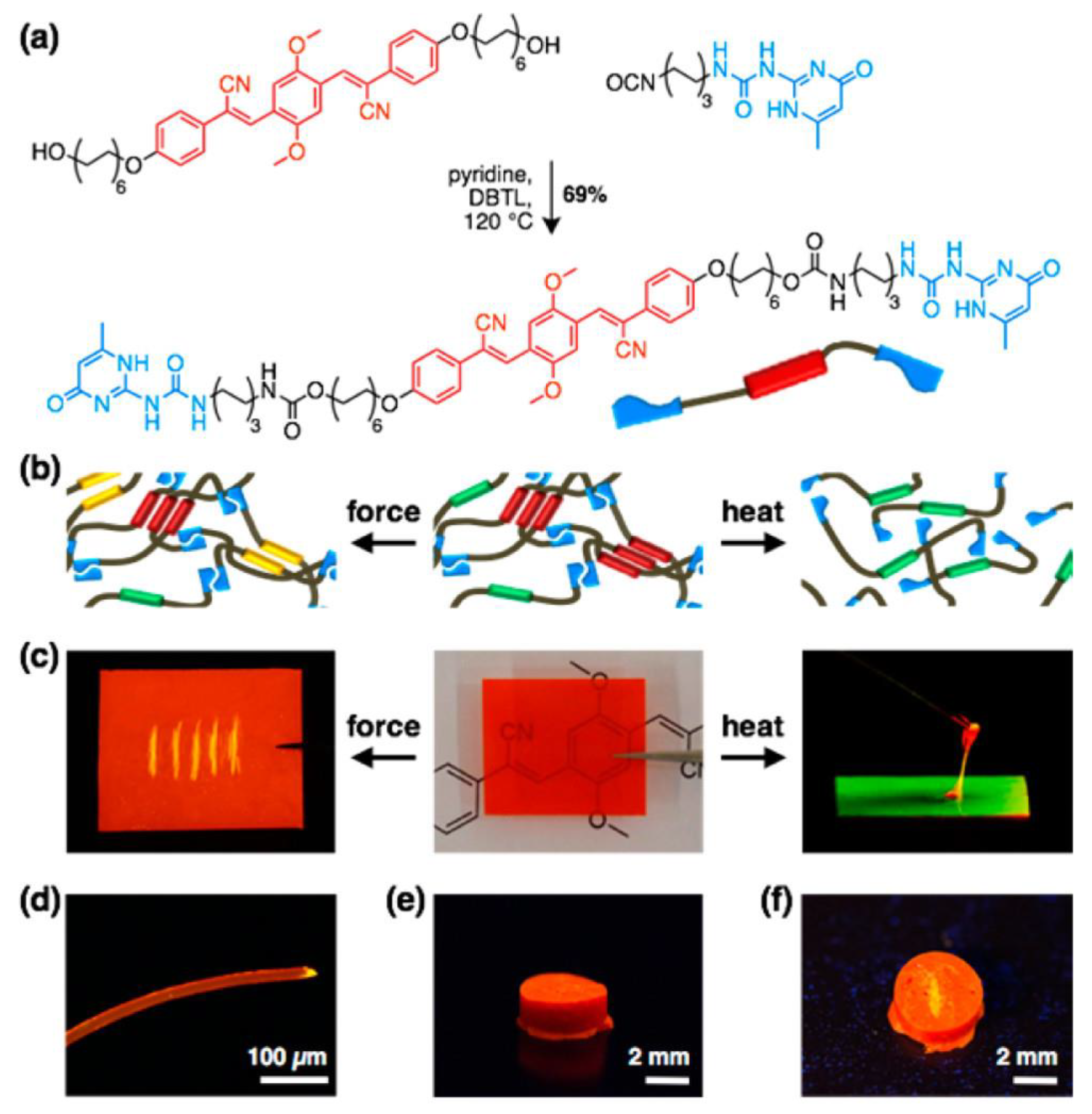

Modulating photophysical properties through changes in environmental stimuli such as light, pH, pressure, heat, electric or magnetic fields, and chemical inputs is a growing area of research in FPs [64][65][66][67]. Mechanoresponsive luminescent (MRL) materials are interesting materials that change their emission color upon application of external forces. Weder and coworkers [68] introduced a novel approach that relies on an MRL compound combined with supramolecular polymerization. They proposed an alternative approach based on the derivatization of MRL chromophores with supramolecular binding motifs. The latter induces dyes to self-assemble into supramolecular polymers, which are then transformed into materials that combine MRL behavior with macromolecular mechanics. Cyano-substituted oligo(p-phenylenevinylene) (cyano-OPV)1,4-bis(α-cyano-4(12-hydroxydodecyloxy)styryl)-2,5-dimethoxybenzene was reacted with 2-(6-isocyanatohexylaminocarbonylamino)-6-methyl-4[1H]-pyrimidinone in hot pyridine, affording the supramolecular UPy-functionalized cyano-OPV, as shown in Figure 3a.

Figure 3. (a) Synthesis of the UPy-functionalized cyano-OPV. (b) Schematic of supramolecular assemblies. (c) Pictures of films made from the UPy-functionalized cyano-OPV, illustrating mechano- (left) and thermoresponsive (right) luminescent behavior. The fluorescence changes from red to yellow upon scratching (left). Upon heating (180 °C), a viscous green-light-emitting fluid is formed, which solidifies into a red-light-emitting solid when cooled (right). (d) Fluorescence microscopy image of a fiber made from 2; note the yellow fluorescing severed edge. (e,f) Photographs of a cylinder made from the UPy-functionalized cyano-OPV before (e) and after (f) scratching its surface. Images displaying fluorescence were recorded under illumination with 365 nm UV light.

The material obtained showed the thermomechanical properties of a supramolecular polymer glass, emitting three distinct colors in solid state (red, yellow, and orange) with MRL and thermoresponsive properties (Figure 3b–f). It is hypothesized that the emission is influenced by molecular packing, which can be altered mechanically [69][70][71]. Controlling mechanochemical polymer scission with another external stimulus may provide a way to advance the fields of polymer chemistry.

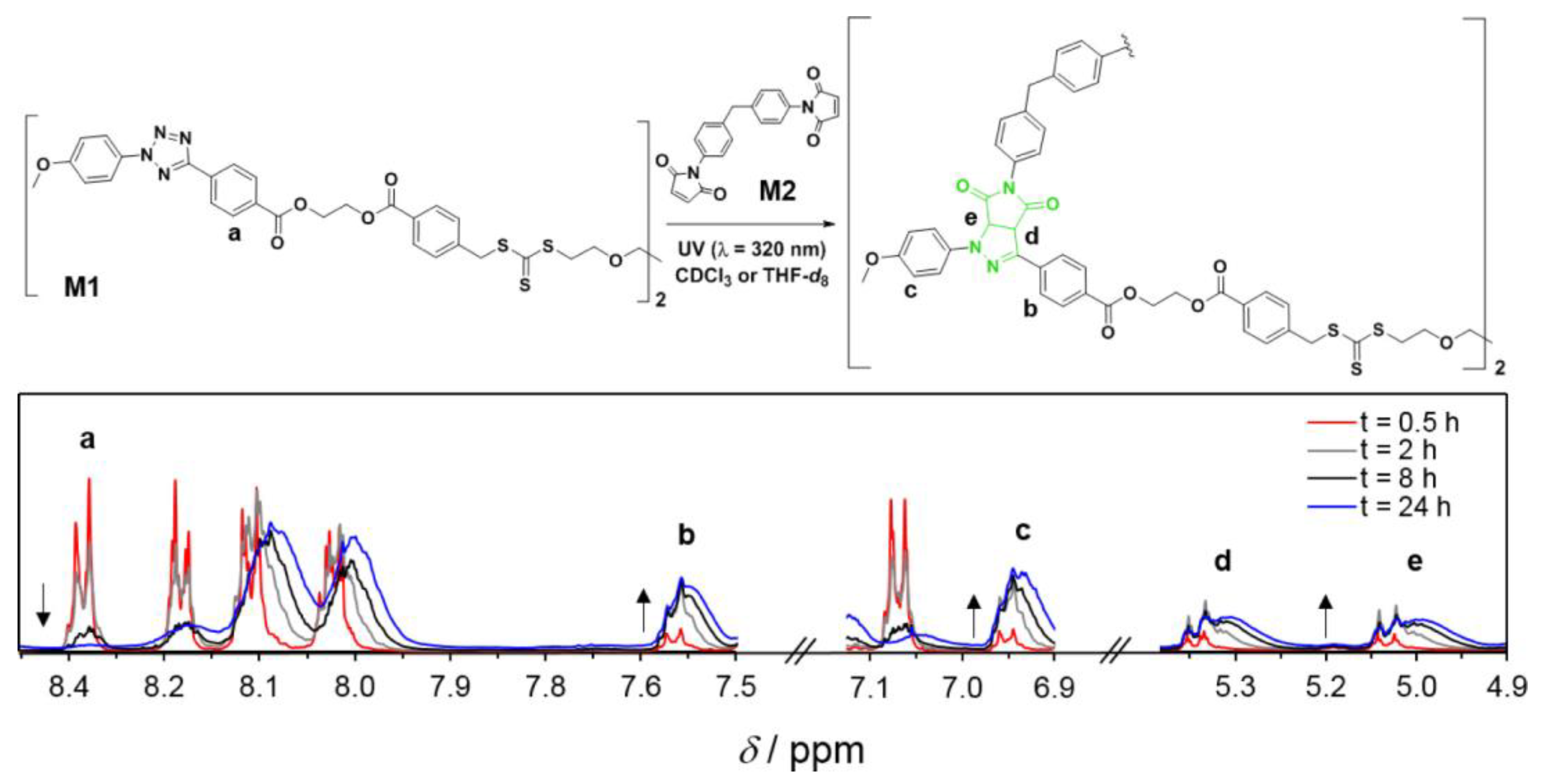

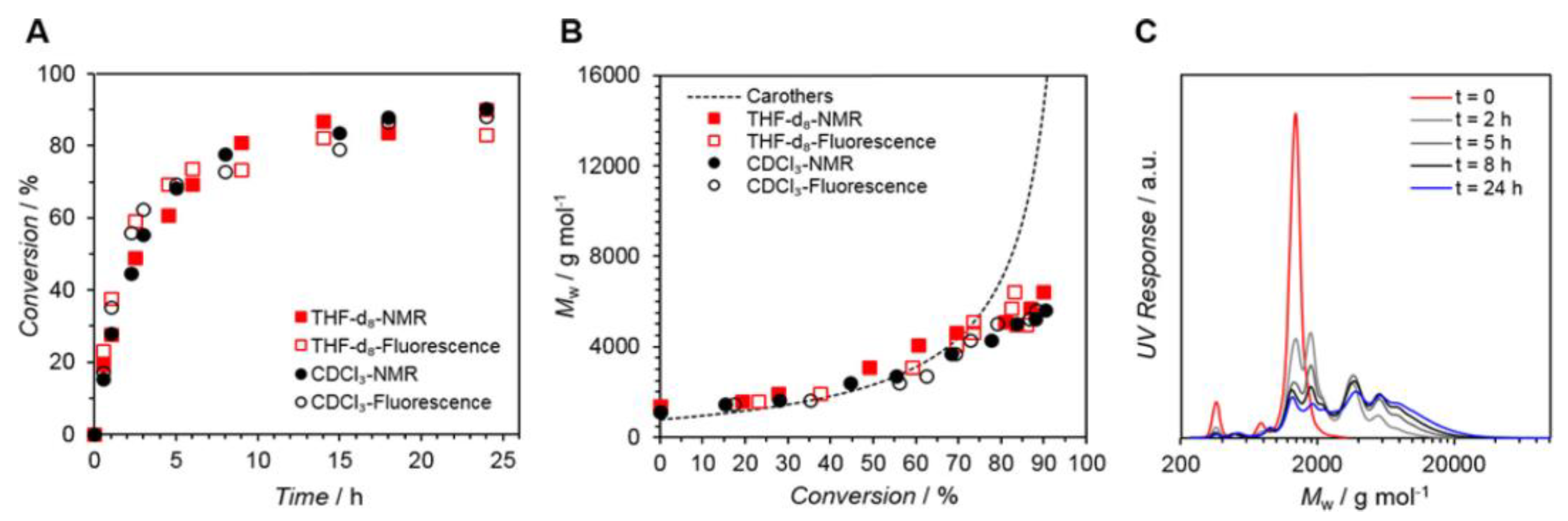

Notably, light-driven reactions in conjunction with fluorescence-based techniques have become a significant synthetic tool in a range of chemical domains; changes in fluorescence are useful for monitoring reaction kinetics. Barner et al. [72] (Figure 4) developed a fluorescence-based methodology to analyze the kinetics of the step-growth polymerization in the photoinduced nitrile imine-mediated tetrazolene cycloaddition (NITEC). The tetrazole moiety rapidly interacts with activated dialkenes when exposed to UV light, resulting in a luminous pyrazoline-containing polymer. As a result, step-growth polymers’ fluorescence emission is proportional to the number of ligation sites in the polymer, resulting in a self-reporting optimal sensor system.

Figure 4. General reaction scheme for the UV-initiated (λmax = 320 nm) step-growth polymerization of monomers M1 (tetrazole RAFT agent) and M2 (bismaleimide), [M1]0 = [M2]0 = 50 mmol L–1, in CDCl3 or THF-d8. The 1H NMR spectra (CDCl3) display the evolution of the signals used to determine the monomer conversion and the pyrazoline yield.

Figure 5 displays a conversion vs. reaction time plot obtained by 1H-NMR and fluorescence spectroscopy, indicating remarkable agreement between the two approaches. After 24 h, conversion rates of up to 90% were attained. In addition, the conversions for photopolymerizations in CDCl3 and THF-d8 exhibit extremely comparable tendencies.

Figure 5. (A) Kinetic plot displaying conversion vs. reaction time for the polymerization of M1,2 (Solvents = THF-d8 or CDCl3. NMR (solid symbols) and fluorescence (open symbols) determined the conversion. (B) Corresponding Mw vs. conversion plot (Carothers curve represented as a dotted line). (C) Mw values determined via SEC analysis.

This method is an exciting tool for monitoring the progress of a reaction, especially when NMR spectroscopy is challenging to use, such as when the backbone NMR resonances overlap with the resonances of interest, when the polymer’s solubility in common deuterated solvents is poor, or when high molecular weight polymers are analyzed.

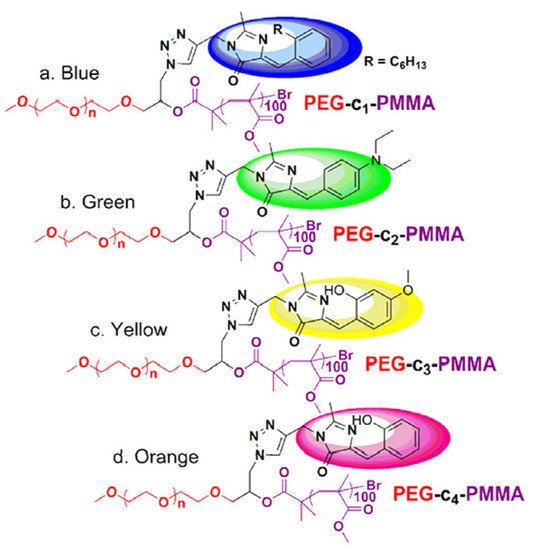

Because of their good biocompatibility, high brightness, and ease of biofunctionalization, FPs have recently gained interest as imaging agents for biological applications; as a result, some examples of NCPs will be disclosed below. In 2015, X. Zhu et al. [73] prepared a set of multicolor fluorescent protein (GFP), by atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) [74] using an azide-modified polyethylene glycol macroinitiator (average molecular weight [Mn] = 12.3 kDa, polydispersity [Đ] = 1.21, yield = 57%). The free azide group was used to attach the fluorophores, following the well-known copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne-1,3- cycloaddition (click chemistry) [75].

The GFP with a color palette ranging from blue to orange was created using a combination of chemically tailoring the core chromophore, showing potential applications for fluorescent color regulation and cell imaging. GFP has received notoriety in biology as a genetically encoded noninvasive luminous marker [76] due to its minimal cytotoxicity and strong photostability. However, the macromolecular assembly showed the highest emission quantum yield (QY), approaching 8%, which is more than 80-fold greater than the core chromophore. The low QY values are attributed to the segmentation effect of polymers, which can diminish intermolecular contacts that quench fluorescence and hinder conformational free rotation (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Polymer structure and their fluorescent color dependence on the fluorophore attached: (a) blue, (b) green, (c) yellow, and (d) orange. Adapted with permission from reference [73].

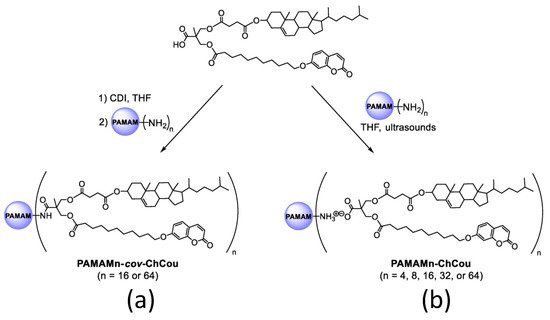

Furthermore, developing effective drug-delivery vehicles is still a difficult task in materials science [77]. Serrano and coworkers [78] described poly(amidoamine) (PAMAM) dendritic core, functionalized with 2,2-Bis(hydroxymethyl)propionic acid (bisMPA) dendrons containing cholesterol and coumarin moieties, resulting in a new class of amphiphilic hybrid dendrimers. Their self-assembly activity was studied in both bulk and water. Because of their perfect macromolecular structure and precise amounts of functional groups, dendrimers are attractive candidates for medicinal applications [79] (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Covalent (a) and ionic (b) functionalization of PAMAM dendrimer with a hybrid bisMPA dendron bearing cholesterol and coumarin moieties.

The synthesized dendrimers created spherical micelles in water due to their amphiphilic nature. The hydrophilic PAMAM cores are exposed at the surface, and the hydrophobic sections (coumarin and cholesterol moieties) remain inside the micelle. The cell survival of the micelles was examined in the HeLa (Henrietta Lacks) [80] cell line as a function of concentration, and all the micelles were shown to be non-toxic after 72 h of incubation at concentrations below 0.75 mg/mL.

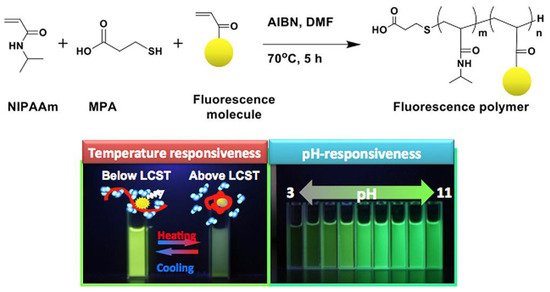

In the same line, the group of Kanazawa [81] reported a reversible temperature-induced phase transition of N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAAm) copolymers with a fluorescent monomer based on fluorescein (FL), coumarin (COU), rhodamine (RH), or dansyl (DA) skeleton, employed as a molecular switch to regulate fluorescence intensity. Furthermore, pH responsiveness was seen in polymers with FL and COU groups, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8. General synthetic scheme for the temperature and pH-responsiveness poly-NIPAAm.

The polymers were synthesized via radical polymerization in dimethylsulfoxide, using azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) and 3-mercaptopropionic acid as the radical initiator and chain-transfer agent, respectively. The weight-averaged molecular weight was determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characterization of synthetic FPs. Reproduced from reference [81].

| Polymer | Mw a | Đ | λex (nm) | λem (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P(NIPAAm-co-FL) | 52,994 | 1.979 | 490 | 515 |

| P(NIPAAm-co-CO) | 47,494 | 1.873 | 376 | 460 |

| P(NIPAAm-co-RH) | 45,905 | 2.028 | 540 | 588 |

| P(NIPAAm-co-DA) | 43,596 | 1.984 | 335 | 526 |

a Determined by GPC using DMF with 10 mM LiCl.

The authors concluded that the switchable emission responses of these polymers were driven by a combination of the properties of both PNIPAAm and the fluorescent molecules. In addition, in vitro experiments into cultured macrophage cells (RAW 264.7) showed that intakes occurred over the lower critical solution temperature (LCST) over 30 °C for the polymers. This behavior is due to a significant increase in cellular absorption of FPs at this temperature, which appears to be caused by dehydration of polymer chains, as found in prior research by the group [82][83].

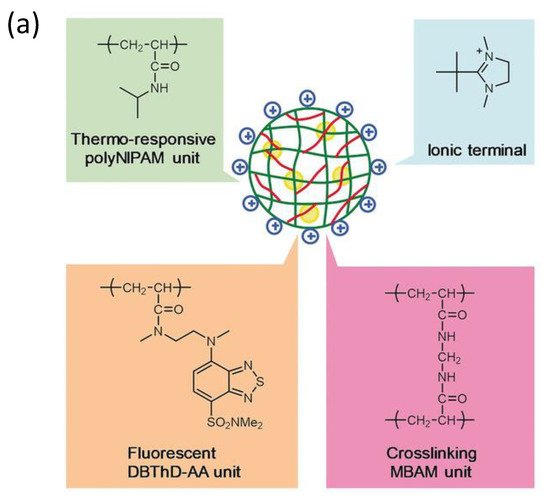

Additionally, following the success in intracellular thermometry, biologists realized the significance of temperature at the single-cell level and demanded that chemists produce more user-friendly fluorescence thermometers [22][84][85]. Recently, Uchiyama et al. [86] (Figure 9) have developed a cationic fluorescent nanogel thermometer (CFNT) based on thermo-responsive N-isopropylacrylamide and environment-sensitive benzothiadiazole (N-(2-{[7-(N,N-Dimethylaminosulfonyl)-2,1,3-benzothiadiazol-4-yl](methyl)amino}ethyl)-N-methylacrylamide; DBThD-AA) [87], exhibiting a great sensitivity to temperature fluctuations in live cells and a remarkable ability to penetrate live mammalian cells in a short incubation period (10 min).

Figure 9. (a) Chemical structure of the CFNT. At lower temperatures, the CFNT swells by absorbing water into its interior, where the environment-sensitive DBThD-AA units are quenched by neighboring water molecules. When heated, CFNT shrinks with the release of water molecules, resulting in fluorescence from the DBThD-AA units. (b) Differential interference contrast (DIC) image, confocal fluorescence image, and merged image of HeLa cells treated with 1 (0.05 w/v%), and (c) DIC image, confocal fluorescence image, and merged image of MOLT-4 cells treated with the CFNT (0.05 w/v%).

This novel fluorescent nanogel thermometer is photobleached resistant in live cells, making it appropriate for long-term internal temperature monitoring, allowing intracellular temperature during cell division.

2.2. Conjugated Polymers Containing Fluorophores

Conjugated polymers’ capacity to act as electronic materials is based on the effective transport of excitons across the polymer chain [88]. In general, the excited state behavior of the corresponding conjugated polymers is dictated by the photophysics of the chromophore monomer. The influence of excited-state lifetimes and molecular conformations on energy transfer is investigated using various molecular architectures [89]. The opportunity lies in the nearly limitless possibilities for producing novel materials for specific uses by merely chemically adjusting the molecular structure. Conjugated polymers can achieve electrical qualities equivalent to non-crystalline inorganic semiconductors; nonetheless, conjugated polymers’ complicated chemical and structural features are nontrivial and mirror those of biomacromolecules. As a result, molecule conformation and interactions are critical to the operation of these material systems.

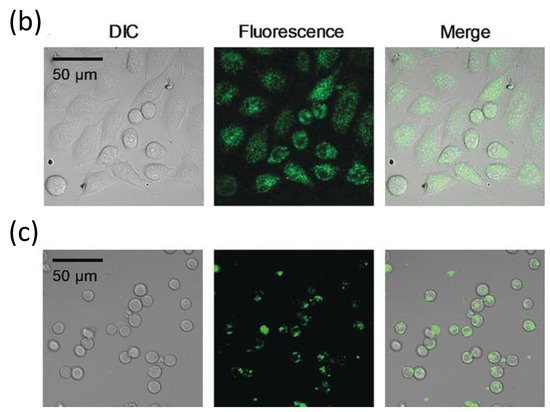

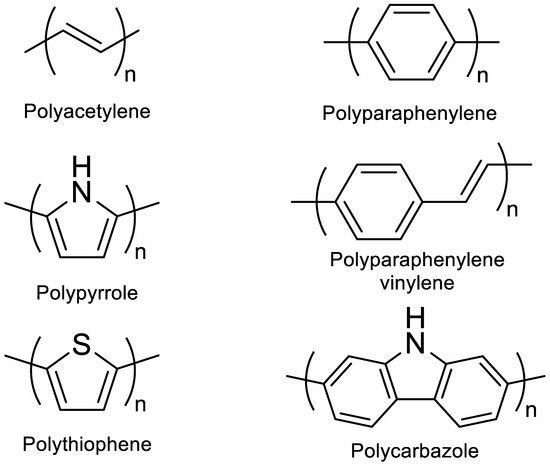

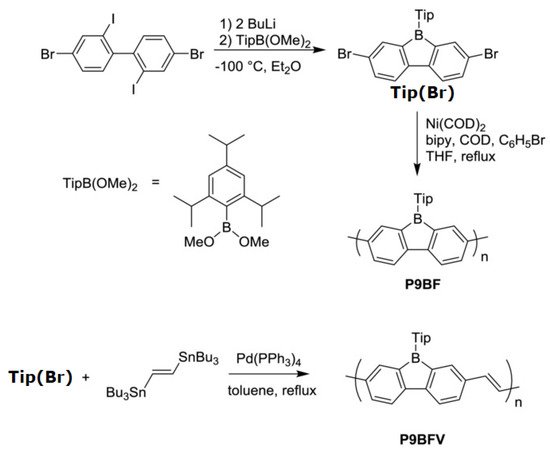

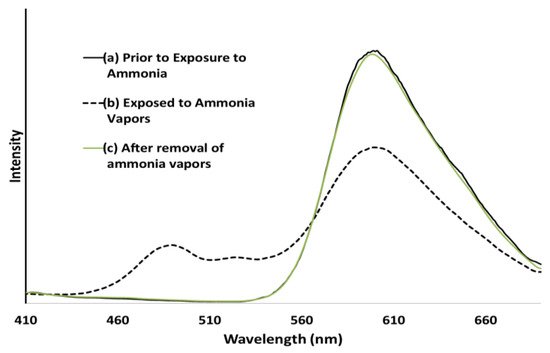

A conjugated carbon chain is a sequence of alternating single and double bonds, with highly delocalized, polarized, and electron-dense π bonds driving its electrical and optical activity. Polyacetylene (PA), polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), polythiophene (PTH), poly(para-phenylene) (PPP), poly(-phenylenevinylene) (PPV), and polyfuran are examples of common conducting polymers (CPs) (Figure 10). Synthetic conducting polymeric materials are widely used in a variety of applications, including packaging, adhesives and lubricants, microelectronic electrical insulators, and implanted biomedical devices [90]. Shirakawa et al. [91] discovered the first conducting polymer, a halogenated derivative of poly(acetylene), opened the door to a burgeoning area of fascinating new uses. The charge carrier mobility (which can be increased by doping) and significant light absorption in the UV–visible range are attributed to the delocalized (conjugated) electronic structure of poly(acetylene). Unfortunately, poly(acetylene) is difficult to manufacture and unstable in the presence of oxygen or water, making it unsuitable for a variety of applications. [92] Moreover, polyacetylene doped with bromine has a million times the conductivity of unadulterated polyacetylene, and this research was recognized with a Nobel Prize in 2000. CPs have recently been developed for use as roll-up displays for computers and mobile phones, flexible solar panels to power portable equipment, and organic light-emitting diodes in displays, in which television screens, luminous traffic, information signs, and light-emitting wallpaper in homes are expected to broaden the use of conjugated polymers as light-emitting polymers [15]. In this context, the insertion of inorganic atoms into the polymer chain is a powerful strategy for changing the characteristics of conjugated polymers. [93] In this context, Rupar et al. [94] reported the preparation of poly(9-borafluorene) vinylene (P9BFV, Figure 11) that showed simultaneous turn-off/turn-on fluorescence responses to fluoride in solution and NH3 (Figure 12) in the gas phase due to the presence of three-coordinate boron. It is important to emphasize that only a small number of conjugated polymers act as optical ammonia sensors [95][96][97].

Figure 10. Classic examples of conducting polymers.

Figure 11. Synthesis of the polymer P9BFV.

Figure 12. (a) Emission spectra of a P9BFV film before exposure to NH3 vapors, (b) emission spectra of a P9BFV film while being exposed to NH3 from aqueous ammonium hydroxide, (c) emission spectra of a P9BFV film 5 min after removal of the NH3 source and NH3 vapors.

The synthesis of the polymer P9BF was conducted via the Yamamoto reductive coupling [98] of Tip (Br). The polymerization is performed with small amounts of bromobenzene, which acts as a capping agent for the step-growth polymerization. On the other hand, the copolymer P9BFV was synthesized via Stille coupling [99].

Compared to the homopolymer P9BF, the prolonged conjugation of P9BFV, owing to the addition of the vinylene group, results in a lower optical bandgap (2.12 eV) and LUMO (4.0 eV, calculated by CV).

P9BFV has a strong solid-state fluorescence with an almost identical spectrum to that observed in the solution. The fluorescence changed from yellow to blue when the film was irradiated with UV light and exposed to ammonia. Furthermore, these alterations are reversible: removing the ammonia atmosphere within 5 min restores P9BFV’s fluorescence spectrum to its normal condition. When thin films of P9BF were exposed to ammonia, they behaved almost identically to P9BFV.

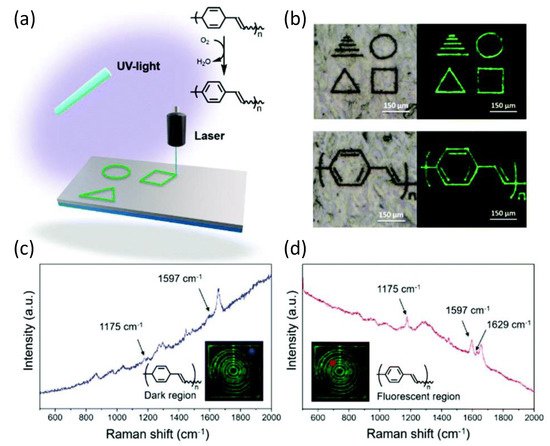

Along with CPs FPs materials, the Bielawski group reported the ring-opening metathesis polymerization of (bicyclo[2.2.2]octa-2,5,7-triene) (barrelene) to prepare copolymers with norbornene, producing robust films [100]. The copolymers prepared underwent spontaneous dehydrogenation in the presence of air or when exposed to laser pulses (phenylene vinylene), affording precisely defined fluorescent patterns with micrometer-sized dimensions. Direct laser writing (DLW) [101] on films of poly(barrelene-co-norbornene) produced a succession of well-defined patterns with micrometer dimensions, which were observed by the fluorescence of the conjugated polymer that formed after irradiation.

As demonstrated by various spectroscopic methods, PPV was produced by spontaneous dehydrogenation of the homo- and copolymers in the presence of air. According to a series of thermal studies, the copolymer displayed an exothermic response when heated to 100 °C, most likely due to oxidation (dehydrogenation), but did not undergo significant mass loss until around 400 °C (under a N2 atmosphere). Thermal aromatization was achieved in seconds after direct laser writing of the barrelene-containing copolymers by using a 400 nm diameter laser beam at a wavelength of 355 nm to write on the substrates that consisted of the copolymer at speeds of approximately 350 μm s−1. Raman spectroscopy was used to look at the dark and luminous portions of the copolymer to see if the laser aided in the oxidation process. The dark parts of Figure 13 showed signals consistent with poly(barrelene-co-norbornene). In contrast, the fluorescent sections showed signals compatible with PPV and consistent with the observations reported by the authors. This chemistry has the inherent advantage of allowing the monomer to be integrated into various macromolecular scaffolds and at different compositions, resulting in a diverse range of materials suitable for laser machining and current lithography applications.

Figure 13. (a) Laser-induced oxidation of poly(barrelene) to polyphenylene vinylene (PPV). (b) Examples of patterns that were written. Photographs were taken under visible light (left) and UV light (λex = 488 nm; right). (c,d) Raman spectra were recorded for the areas indicated in blue or red (see insets) of a film subjected to DLW. The films were prepared by drop-casting a solution of poly(barrelene-co-norbornene) (200 mg) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) into a PTFE mold.

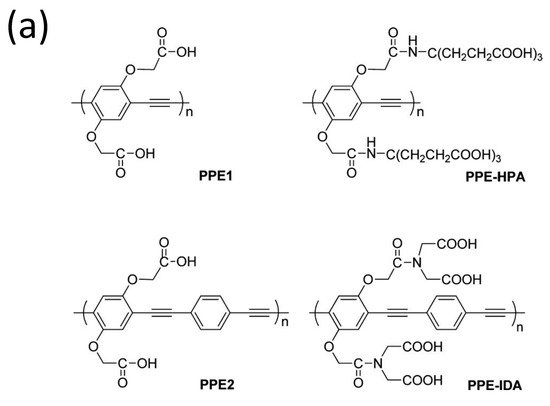

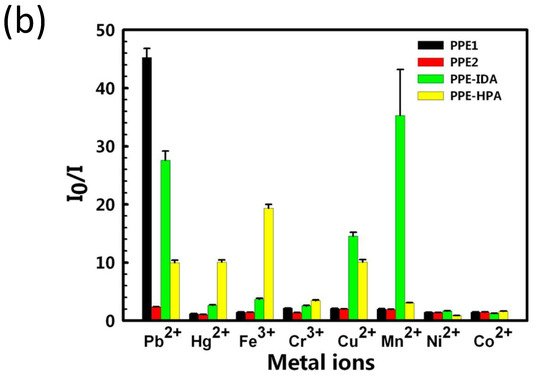

Because of its increased detection sensitivity in the detection of a wide range of environmental contaminants and bioactive chemicals, conjugated polymer-based sensors have received a lot of interest [102][103][104][105]. Since the first conjugated polymer sensor was reported in the 1990s, this sensing platform has advanced more than two decades, with an explosion of research in this sector noted in the previous 10 years [106]. For instance, water-soluble conjugated polymers with ionic side chains are known as conjugated polyelectrolytes (CPEs) [107][108][109][110][111], and they have garnered attention in the past decade mainly because of their application as sensors, energy converters, and antimicrobials [112][113][114][115]. For example, Tan et al. [116] developed and synthesized four anionic CPEs with a poly(paraphenylene ethynylene) (PPE, Figure 14a) backbone but varied pendant ionic side chains. These CPEs were shown to attach to metal ions with varying selectivities via polymer–metal ion interactions, resulting in a wide range of fluorescence responses. Four CPEs were structurally and photophysically characterized and used as PPE sensor arrays. The sensor array’s fluorescence intensity responses were tested after the injection of eight different metal ions separately.

Figure 14. (a) Structures of the four conjugated polyelectrolytes, PPE1, PPE2, PPE−IDA, and PPE−HPA, (b) response patterns constructed based on fluorescence quenching of the four polymers by eight metal ions at 5 μM each. The response patterns were generated from the ratios of the polymers’ initial to final emission intensities. Error bars represent the standard deviations of six replicates for each PPE−metal ion pair. Polymers are PPE1, PPE2, PPE−IDA, and PPE−HPA, and metal ions are Pb2+, Hg2+, Fe3+, Cr3+, Cu2+, Mn2+, Ni2+, and Co2+.

This approach generated environmentally friendly fluorescent materials, with easy sample preparation and measurements and convenient data processing with a simple pattern analysis procedure that distinguishes from other existing methods. The authors improved the methodology for detecting combinations of harmful metal ions, with the possibility of expanding to other metal ions in the future.

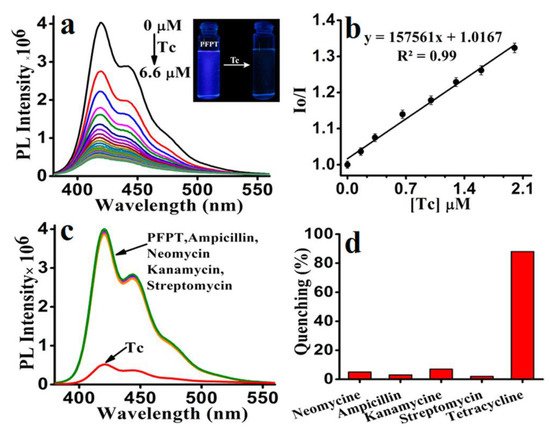

The development of new detecting methodologies based on FPs has also been extended to organic molecules. Tetracycline (Tc), for example, is a type of antibiotic that is commonly used in veterinary medicine, human treatment, and agriculture, and it is critical to measure in water. The development of simple and efficient methods for detecting and removing TC from water is highly desirable but continues to be a challenge. Because of major environmental concerns, including ecological hazards and human health consequences, tetracyclines are a special case among the many antibiotics used. Most data suggest that tetracycline antibiotics are ubiquitous substances found in many ecological compartments due to their widespread use [117][118]. More than 70% of tetracycline antibiotics are excreted and released inactive form into the environment after administration via urine and feces from people and animals. Because of their very hydrophilic nature and low volatility, they have demonstrated great endurance in the aquatic environment [119]. Iyer et al. [120] synthesized a CPE following a palladium-catalyzed Suzuki cross-coupling polymerization, poly[5,5′-(((2-phenyl-9H-fluorene-9,9-diyl)bis(hexane-6,1-diyl))bis(oxy))diisophthalate] sodium (PFPT), and used it for highly sensitive detection of tetracycline in water (Figure 15).

Figure 15. (a) Fluorescence spectra of PFPT (6.6 μM) with increasing concentration of Tc (6.6 μM) in aqueous media (HEPES 10 mM, pH 7.4). Inset: color change of PFPT under UV light (lamp excited at 365 nm) before and after adding Tc. (b) Stern–Volmer plot of PFPT upon the addition of Tc in aqueous media. Effect of Tc (6.6 μM) and various other antibiotics (6.6 μM) on the (c) emission spectra of PFPT and their corresponding (d) bar diagram depicting the quenching percentage.

Due to the electron-rich nature of the polymer PFPT, cyclic voltammetry analysis revealed only the oxidation peak, from which the HOMO level was determined to be 5.95 eV. From the beginning of the UV–vis absorption spectrum, the optical band gap was calculated to be 3.35 eV, whereas the LUMO level was determined to be 2.6 eV. The HOMO (7.55 eV) and LUMO (4.53 eV) energies of tetracycline were also determined using cyclic voltammetry and onset UV–vis measurements. These results demonstrate that photoinduced electron transfer from the polymer’s LUMO (2.6 eV) to the quencher Tc’s LUMO (4.53 eV) is the sole mechanism by which Tc selectively quenches PFPT fluorescence.

In 100% aqueous media, the detection limit of PFPT toward Tc is reported to be 14.35 nM/6.80 ppb (6.8 ng/mL). The effective electron transport from PFPT to Tc via electrostatic/hydrogen bonding interactions resulted in a high quenching efficiency with a Ksv value of 1.57 × 105 M−1.

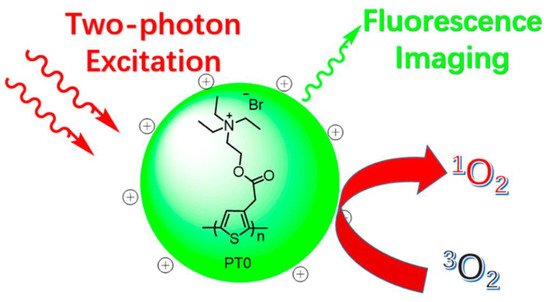

As well as sensing materials [54], CPs have been intensively researched for biosensing and bioimaging applications due to their great light-harvesting capacity, outstanding photostability, and easily surface-modifiable features [121][122][123]. For instance, photodynamic therapy (PDT) [124][125] has become an important cancer treatment that uses reactive oxygen species (ROS) (such 1O2 and hydroxyl radicals) created by exposing photosensitizers (PS) to light irradiation in an oxygen-rich environment to destroy cancer cells. Zhang and coworkers [126] prepared a positively charged water-soluble polythiophene polymer (PT0, Figure 16). This exhibited high photo- and pH-stability, a sizeable two-photon absorption cross-section, and the capability to generate 1O2 (g).

Figure 16. Illustration of PT0 for simultaneous two-photon excitation fluorescence imaging and photodynamic therapy.

Irradiation using 780 and 900 nm lasers of 406, and 473 mW of laser power, respectively, with prolonged irradiation (4 to 5 min) was needed to kill HeLa cells efficiently. Although PT0 does not appear to distinguish cancer cells from noncancerous cells, such selectivity might be achieved via a method such as combining PT0 with a cancer cell targeting probe, which will require additional investigation.

References

- Braslavsky, S.E. Glossary of terms used in photochemistry, 3rd edition (IUPAC Recommendations 2006). Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79, 293–465.

- Lakowicz, J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Lakowicz, J.R., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-387-46312-4.

- Guilbault, G.G.; Norris, J.D. Practical Fluorescence, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781003066514.

- McNaught, A.D.; Wilkinson, A.; IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology (The ’Gold Book’), 2nd ed.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1997.

- Jin, Y.; Gao, X. Plasmonic fluorescent quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 571–576.

- Huang, C.-C.; Yang, Z.; Lee, K.-H.; Chang, H.-T. Synthesis of Highly Fluorescent Gold Nanoparticles for Sensing Mercury(II). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 119, 6948–6952.

- Baker, S.N.; Baker, G.A. Luminescent Carbon Nanodots: Emergent Nanolights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6726–6744.

- El-Safty, S.A.; Shenashen, M.; Ismael, M.; Khairy, M.; Awual, R. Mesoporous aluminosilica sensors for the visual removal and detection of Pd(II) and Cu(II) ions. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 166, 195–205.

- Crego-Calama, M.; Reinhoudt, D.N. New Materials for Metal Ion Sensing by Self-Assembled Monolayers on Glass. Adv. Mater. 2001, 13, 1171–1174.

- Huang, C.-C.; Yang, Z.; Lee, K.-H.; Chang, H.-T. Synthesis of Highly Fluorescent Gold Nanoparticles for Sensing Mercury(II). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6824–6828.

- Larson, D.R.; Zipfel, W.R.; Williams, R.M.; Clark, S.W.; Bruchez, M.P.; Wise, F.W.; Webb, W.W. Water-Soluble Quantum Dots for Multiphoton Fluorescence Imaging In Vivo. Science 2003, 300, 1434–1436.

- Sharker, S.; Do, M. Nanoscale Carbon-Polymer Dots for Theranostics and Biomedical Exploration. J. Nanotheranostics 2021, 2, 118–130.

- Chatterjee, D.P.; Pakhira, M.; Nandi, A.K. Fluorescence in Nonfluorescent” Polymers. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 30747–30766.

- Ren, J.; Stagi, L.; Innocenzi, P. Fluorescent carbon dots in solid-state: From nanostructures to functional devices. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2021, 62, 100295.

- AlSalhi, M.S.; Alam, J.; Dass, L.A.; Raja, M. Recent Advances in Conjugated Polymers for Light Emitting Devices. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 2036–2054.

- Park, J.M.; Nam, S.H.; Hong, K.-I.; Jeun, Y.E.; Ahn, H.S.; Jang, W.-D. Stimuli-responsive fluorescent dyes for electrochemically tunable multi-color-emitting devices. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 332, 129534.

- Yao, Z.; Zong, W.; Wang, K.; Yuan, P.; Liu, Y.; Xu, S.; Cao, S. Triphenylamine-carbazole alternating copolymers bearing thermally activated delayed fluorescent emitting and host pendant groups for solution-processable OLEDs. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 163, 104898.

- Minotto, A.; Bulut, I.; Rapidis, A.G.; Carnicella, G.; Patrini, M.; Lunedei, E.; Anderson, H.L.; Cacialli, F. Towards efficient near-infrared fluorescent organic light-emitting diodes. Light. Sci. Appl. 2021, 10, 18.

- Li, T.; Yu, L.; Jin, D.; Chen, B.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. A colorimetric and fluorescent probe for fluoride anions based on a phenanthroimidazole–cyanine platform. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 1612–1616.

- Weldeab, A.O.; Li, L.; Cekli, S.; Abboud, K.A.; Schanze, K.S.; Castellano, R.K. Pyridine-terminated low gap π-conjugated oligomers: Design, synthesis, and photophysical response to protonation and metalation. Org. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 3170–3177.

- Saremi, B.; Bandi, V.; Kazemi, S.; Hong, Y.; D’Souza, F.; Yuan, B. Exploring NIR Aza-BODIPY-Based Polarity Sensitive Probes with ON-and-OFF Fluorescence Switching in Pluronic Nanoparticles. Polymers 2020, 12, 540.

- Hayashi, T.; Kawamoto, K.; Inada, N.; Uchiyama, S. Cationic Fluorescent Nanogel Thermometers based on Thermoresponsive Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) and Environment-Sensitive Benzofurazan. Polymers 2019, 11, 1305.

- Zhao, W.-X.; Zhou, C.; Peng, H.-S. Ratiometric Luminescent Nanoprobes Based on Ruthenium and Terbium-Containing Metallopolymers for Intracellular Oxygen Sensing. Polymers 2019, 11, 1290.

- Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Wei, Y.; Luo, A. Magnetic Fluorescence Molecularly Imprinted Polymer Based on FeOx/ZnS Nanocomposites for Highly Selective Sensing of Bisphenol A. Polymers 2019, 11, 1210.

- Yamagishi, H.; Matsui, T.; Kitayama, Y.; Aikyo, Y.; Tong, L.; Kuwabara, J.; Kanbara, T.; Morimoto, M.; Irie, M.; Yamamoto, Y. Fluorescence Switchable Conjugated Polymer Microdisk Arrays by Cosolvent Vapor Annealing. Polymers 2021, 13, 269.

- Shchapova, E.; Nazarova, A.; Gurkov, A.; Borvinskaya, E.; Rzhechitskiy, Y.; Dmitriev, I.; Meglinski, I.; Timofeyev, M. Application of PEG-Covered Non-Biodegradable Polyelectrolyte Microcapsules in the Crustacean Circulatory System on the Example of the Amphipod Eulimnogammarus verrucosus. Polymers 2019, 11, 1246.

- Li, Q.; Zhang, W.-C.; Wang, C.-F.; Chen, S. In situ access to fluorescent dual-component polymers towards optoelectronic devices via inhomogeneous biphase frontal polymerization. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 102294–102299.

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.-M.; Zhu, W.-Y.; Zhang, C.-H.; Tang, H.; Jiang, J.-H. Conjugated polymer nanoparticles-based fluorescent biosensor for ultrasensitive detection of hydroquinone. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2018, 1012, 60–65.

- Lichon, L.; Kotras, C.; Myrzakhmetov, B.; Arnoux, P.; Daurat, M.; Nguyen, C.; Durand, D.; Bouchmella, K.; Ali, L.M.; Durand, J.-O.; et al. Polythiophenes with Cationic Phosphonium Groups as Vectors for Imaging, siRNA Delivery, and Photodynamic Therapy. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1432.

- Hu, L.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Tian, B.; Guo, T.; Liu, R.; Wang, C.; Ying, L. In Vivo Bioimaging and Photodynamic Therapy Based on Two-Photon Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers Containing Dibenzothiophene-S,S-dioxide Derivatives. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 57281–57289.

- Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yan, S. Highly efficient white-emitting thermally activated delayed fluorescence polymers: Synthesis, non-doped white OLEDs and electroluminescent mechanism. Nano Energy 2019, 65, 104057.

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, P.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Xie, H.; Zhang, C.; Cui, J.; Chen, J. Dual photochromics-contained photoswitchable multistate fluorescent polymers for advanced optical data storage, encryption, and photowritable pattern. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 131557.

- Wang, M.; Jiang, K.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Ji, H.; Zheng, T.; Feng, H. A facile fabrication of conjugated fluorescent nanoparticles and micro-scale patterned encryption via high resolution inkjet printing. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 14337–14345.

- Abdollahi, A.; Alidaei-Sharif, H.; Roghani-Mamaqani, H.; Herizchi, A. Photoswitchable fluorescent polymer nanoparticles as high-security anticounterfeiting materials for authentication and optical patterning. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 5476–5493.

- Ru, Y.; Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Liu, Z.; Feng, H.; Wang, B.; Guo, M.; Wang, X.; Luo, C.; Yang, W.; et al. A new family of thermoplastic photoluminescence polymers. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 6250–6256.

- Zhai, Y.-L.; Wang, Q.-B.; Yu, H.; Ji, X.-Y.; Zhang, X. Enhanced Two-Photon Fluorescence and Fluorescence Imaging of Novel Probe for Calcium Ion by Self-Assembly with Conjugated Polymer. Polymers 2019, 11, 1643.

- Ostos, F.J.; Iasilli, G.; Carlotti, M.; Pucci, A. High-Performance Luminescent Solar Concentrators Based on Poly(Cyclohexylmethacrylate) (PCHMA) Films. Polymers 2020, 12, 2898.

- Wang, B.; Yoshida, K.; Sato, K.; Anzai, J.-I. Phenylboronic Acid-Functionalized Layer-by-Layer Assemblies for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2017, 9, 202.

- Chen, J.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Hong, W.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X. The Glass-Transition Temperature of Supported PMMA Thin Films with Hydrogen Bond/Plasmonic Interface. Polymers 2019, 11, 601.

- Yin, M.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Deng, Q.; Wang, S. Highly Sensitive Detection of Benzoyl Peroxide Based on Organoboron Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers. Polymers 2019, 11, 1655.

- Gou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, Y.; Lin, W. Synthesis of Silane-Based Poly(thioether) via Successive Click Reaction and Their Applications in Ion Detection and Cell Imaging. Polymers 2019, 11, 1235.

- Luthjens, L.H.; Yao, T.; Warman, J.M. A Polymer-Gel Eye-Phantom for 3D Fluorescent Imaging of Millimetre Radiation Beams. Polymers 2018, 10, 1195.

- Bidan, G.; Billon, M.; Livache, T.; Mathis, G.; Roget, A.; Torres-Rodriguez, L. Conducting polymers as a link between biomolecules and microelectronics. Synth. Met. 1999, 102, 1363–1365.

- Lange, U.; Roznyatovskaya, N.V.; Mirsky, V.M. Conducting polymers in chemical sensors and arrays. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2008, 614, 1–26.

- Livache, T.; Bazin, H.; Mathis, G. Conducting polymers on microelectronic devices as tools for biological analyses. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1998, 278, 171–176.

- Disney, M.D.; Zheng, J.; Swager, A.T.M.; Seeberger, P.H. Detection of Bacteria with Carbohydrate-Functionalized Fluorescent Polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13343–13346.

- Yan, J.-J.; Wang, Z.K.; Lin, X.-S.; Hong, C.-Y.; Liang, H.-J.; Pan, C.-Y.; You, Y.-Z. Polymerizing Nonfluorescent Monomers without Incorporating any Fluorescent Agent Produces Strong Fluorescent Polymers. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 5617–5624.

- Hong, Y.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 5361–5388.

- Würthner, F. Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE): A Historical Perspective. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 14192–14196.

- Hu, R.; Qin, A.; Tang, B.Z. AIE polymers: Synthesis and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 100, 101176.

- Hu, R.; Kang, Y.; Tang, B.Z. Recent advances in AIE polymers. Polym. J. 2016, 48, 359–370.

- Hu, R.; Yang, X.; Qin, A.; Tang, B.Z. AIE polymers in sensing, imaging and theranostic applications. Mater. Chem. Front. 2021, 5, 4073–4088.

- Zhan, R.; Pan, Y.; Manghnani, P.; Liu, B. AIE Polymers: Synthesis, Properties, and Biological Applications. Macromol. Biosci. 2017, 17, 1600433.

- Thomas, S.W.; Joly, G.D.; Swager, T.M. Chemical Sensors Based on Amplifying Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1339–1386.

- Alvarez, A.; Costa-Fernández, J.M.; Pereiro, R.; Sanz-Medel, A.; Salinas-Castillo, A. Fluorescent conjugated polymers for chemical and biochemical sensing. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2011, 30, 1513–1525.

- Braunecker, W.A.; Matyjaszewski, K. Controlled/living radical polymerization: Features, developments, and perspectives. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 93–146.

- Grubbs, R.B.; Grubbs, R.H. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Living Polymerization—Emphasizing the Molecule in Macromolecules. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 6979–6997.

- Sánchez-Ruiz, A.; Sousa-Hervés, A.; Tolosa, B.J.; Navarro, A.; García-Martínez, J.C. Aggregation-Induced Emission Properties in Fully π-Conjugated Polymers, Dendrimers, and Oligomers. Polymers 2021, 13, 213.

- Zhao, J.; Pan, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, X. Novel AIEgen-Functionalized Diselenide-Crosslinked Polymer Gels as Fluorescent Probes and Drug Release Carriers. Polymers 2020, 12, 551.

- Wu, F.; Misra, M.; Mohanty, A.K. Challenges and new opportunities on barrier performance of biodegradable polymers for sustainable packaging. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 117, 101395.

- Rai, P.; Mehrotra, S.; Priya, S.; Gnansounou, E.; Sharma, S.K. Recent advances in the sustainable design and applications of biodegradable polymers. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 325, 124739.

- Namsheer, K.; Rout, C.S. Conducting polymers: A comprehensive review on recent advances in synthesis, properties and applications. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 5659–5697.

- de Leon, A.C.C.; da Silva Ítalo, G.; Pangilinan, K.D.; Chen, Q.; Caldona, E.B.; Advincula, R.C. High performance polymers for oil and gas applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 162, 104878.

- Nandi, M.; Maiti, B.; Srikanth, K.; De, P. Supramolecular Interaction-Assisted Fluorescence and Tunable Stimuli-Responsiveness of l-Phenylalanine-Based Polymers. Langmuir 2017, 33, 10588–10597.

- Kwak, G.; Lee, W.-E.; Jeong, H.; Sakaguchi, T.; Fujiki, M. Swelling-Induced Emission Enhancement in Substituted Acetylene Polymer Film with Large Fractional Free Volume: Fluorescence Response to Organic Solvent Stimuli. Macromolecules 2008, 42, 20–24.

- Saha, B.; Bauri, K.; Bag, A.; Ghorai, P.K.; De, P. Conventional fluorophore-free dual pH- and thermo-responsive luminescent alternating copolymer. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 6895–6900.

- Dou, C.; Han, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Multi-Stimuli-Responsive Fluorescence Switching of a Donor−Acceptor π-Conjugated Compound. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 666–670.

- Lavrenova, A.; Balkenende, D.W.R.; Sagara, Y.; Schrettl, S.; Simon, Y.C.; Weder, C. Mechano- and Thermoresponsive Photoluminescent Supramolecular Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 4302–4305.

- Sagara, Y.; Yamane, S.; Mitani, M.; Weder, C.; Kato, T. Mechanoresponsive Luminescent Molecular Assemblies: An Emerging Class of Materials. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1073–1095.

- Pucci, A.; Bizzarri, R.; Ruggeri, G. Polymer composites with smart optical properties. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 3689–3700.

- Sagara, Y.; Kato, T. Mechanically induced luminescence changes in molecular assemblies. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 605–610.

- Estupiñán, D.; Gegenhuber, T.; Blinco, J.; Barner-Kowollik, C.; Barner, L. Self-Reporting Fluorescent Step-Growth RAFT Polymers Based on Nitrile Imine-Mediated Tetrazole-ene Cycloaddition Chemistry. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 229–234.

- Deng, H.; Su, Y.; Hu, M.; Jin, X.; He, L.; Pang, Y.; Dong, R.; Zhu, X. Multicolor Fluorescent Polymers Inspired from Green Fluorescent Protein. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 5969–5979.

- Matyjaszewski, K. Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization (ATRP): Current Status and Future Perspectives. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4015–4039.

- Worrell, B.T.; Malik, J.A.; Fokin, V.V. Direct Evidence of a Dinuclear Copper Intermediate in Cu(I)-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloadditions. Science 2013, 340, 457–460.

- Chalfie, M.; Tu, Y.; Euskirchen, G.; Ward, W.W.; Prasher, D.C. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science 1994, 263, 802–805.

- Elsabahy, M.; Wooley, K.L. Design of polymeric nanoparticles for biomedical delivery applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2545–2561.

- Concellón, A.; Anselmo, M.S.; Hernández-Ainsa, S.; Romero, P.; Marcos, M.; Serrano, J.L. Micellar Nanocarriers from Dendritic Macromolecules Containing Fluorescent Coumarin Moieties. Polymers 2020, 12, 2872.

- Palmerston Mendes, L.; Pan, J.; Torchilin, V.P. Dendrimers as Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid and Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Molecules 2017, 22, 1401.

- Lucey, B.P.; Nelson-Rees, W.A.; Hutchins, G.M. Henrietta Lacks, HeLa Cells, and Cell Culture Contamination. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2009, 133, 1463–1467.

- Yamada, A.; Hiruta, Y.; Wang, J.; Ayano, E.; Kanazawa, H. Design of Environmentally Responsive Fluorescent Polymer Probes for Cellular Imaging. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 2356–2362.

- Hiruta, Y.; Shimamura, M.; Matsuura, M.; Maekawa, Y.; Funatsu, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Ayano, E.; Okano, T.; Kanazawa, H. Temperature-Responsive Fluorescence Polymer Probes with Accurate Thermally Controlled Cellular Uptakes. ACS Macro Lett. 2014, 3, 281–285.

- Hiruta, Y.; Funatsu, T.; Matsuura, M.; Wang, J.; Ayano, E.; Kanazawa, H. pH/temperature-responsive fluorescence polymer probe with pH-controlled cellular uptake. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 207, 724–731.

- Okabe, K.; Inada, N.; Gota, C.; Harada, Y.; Funatsu, T.; Uchiyama, S. Intracellular temperature mapping with a fluorescent polymeric thermometer and fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 705.

- Gota, C.; Okabe, K.; Funatsu, T.; Harada, Y.; Uchiyama, S. Hydrophilic Fluorescent Nanogel Thermometer for Intracellular Thermometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2766–2767.

- Uchiyama, S.; Tsuji, T.; Kawamoto, K.; Okano, K.; Fukatsu, E.; Noro, T.; Ikado, K.; Yamada, S.; Shibata, Y.; Hayashi, T.; et al. A Cell-Targeted Non-Cytotoxic Fluorescent Nanogel Thermometer Created with an Imidazolium-Containing Cationic Radical Initiator. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5413–5417.

- Uchiyama, S.; Kimura, K.; Gota, C.; Okabe, K.; Kawamoto, K.; Inada, N.; Yoshihara, T.; Tobita, S. Environment-Sensitive Fluorophores with Benzothiadiazole and Benzoselenadiazole Structures as Candidate Components of a Fluorescent Polymeric Thermometer. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2012, 18, 9552–9563.

- Patil, A.O.; Heeger, A.J.; Wudl, F. Optical properties of conducting polymers. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 183–200.

- Andrew, T.L.; Swager, T.M. Structure-Property relationships for exciton transfer in conjugated polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2011, 49, 476–498.

- Das, T.K.; Prusty, S. Review on Conducting Polymers and Their Applications. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2012, 51, 1487–1500.

- Chiang, C.K.; Fincher, C.R., Jr.; Park, Y.W.; Heeger, A.J.; Shirakawa, H.; Louis, E.J.; Gau, S.C.; MacDiarmid, A.G. Electrical Conductivity in Doped Polyacetylene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1977, 39, 1098–1101.

- Hudson, B.S. Polyacetylene: Myth and Reality. Materials 2018, 11, 242.

- He, X.; Baumgartner, T. Conjugated main-group polymers for optoelectronics. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 11334–11350.

- Adams, I.A.; Rupar, P.A. A Poly(9-Borafluorene) Homopolymer: An Electron-Deficient Polyfluorene with “Turn-On” Fluorescence Sensing of NH3 Vapor. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015, 36, 1336–1340.

- Kukla, A.; Shirshov, Y.; Piletsky, S. Ammonia sensors based on sensitive polyaniline films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1996, 37, 135–140.

- Hibbard, T.; Crowley, K.; Kelly, F.; Ward, F.; Holian, J.; Watson, A.; Killard, A.J. Point of Care Monitoring of Hemodialysis Patients with a Breath Ammonia Measurement Device Based on Printed Polyaniline Nanoparticle Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 12158–12165.

- Timmer, B.; Olthuis, W.; Van Den Berg, A. Ammonia sensors and their applications—A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2005, 107, 666–677.

- Zhou, Z.-H.; Yamamoto, T. Research on carbon—carbon coupling reactions of haloaromatic compounds mediated by zerovalent nickel complexes. Preparation of cyclic oligomers of thiophene and benzene and stable anthrylnickel(II) complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 1991, 414, 119–127.

- Stille, J.K. The Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organotin Reagents with Organic Electrophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1986, 25, 508–524.

- Tang, T.; Ahumada, G.; Bielawski, C.W. Direct laser writing of poly(phenylene vinylene) on poly(barrelene). Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 5437–5443.

- Selimis, A.; Mironov, V.; Farsari, M. Direct laser writing: Principles and materials for scaffold 3D printing. Microelectron. Eng. 2015, 132, 83–89.

- Chen, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Duan, H.; Fan, L.-J. Amphiphilic Conjugated Polyelectrolyte-Based Sensing System for Visually Observable Detection of Neomycin with High Sensitivity. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 2088–2097.

- Wu, P.; Tan, C. Biological Sensing and Imaging Using Conjugated Polymers and Peptide Substrates. Protein Pept. Lett. 2021, 28, 2–10.

- Pak, Y.L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Q. Conjugated polymer based fluorescent probes for metal ions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 433, 213745.

- Zhao, X.; Dai, X.; Zhao, S.; Cui, X.; Gong, T.; Song, Z.; Meng, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, B. Aptamer-based fluorescent sensors for the detection of cancer biomarkers. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 247, 119038.

- Wang, T.; Zhang, N.; Bai, W.; Bao, Y. Fluorescent chemosensors based on conjugated polymers with N-heterocyclic moieties: Two decades of progress. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 3095–3114.

- Zhang, L.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Xinyan, H.; Ding, L. Fluorescent Binary Ensemble Based on Pyrene Derivative and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Assemblies as a Chemical Tongue for Discriminating Metal Ions and Brand Water. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1821–1830.

- Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, D.P.; Das, S.; Mukhopadhyay, T.K.; Datta, A.; Nandi, A.K. Influence of Hofmeister I− on Tuning Optoelectronic Properties of Ampholytic Polythiophene by Varying pH and Conjugating with RNA. Langmuir 2017, 33, 12739–12749.

- Chang, C.-C.; Wang, G.; Takarada, T.; Maeda, M. Iodine-Mediated Etching of Triangular Gold Nanoplates for Colorimetric Sensing of Copper Ion and Aptasensing of Chloramphenicol. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 34518–34525.

- Han, J.; Wang, B.; Bender, M.; Kushida, S.; Seehafer, K.; Bunz, U.H.F. Poly(aryleneethynylene) Tongue That Identifies Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Water: A Test Case for Combating Counterfeit Drugs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 790–797.

- Han, J.; Wang, B.; Bender, M.; Seehafer, K.; Bunz, U.H.F. Water-Soluble Poly(p-aryleneethynylene)s: A Sensor Array Discriminates Aromatic Carboxylic Acids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 20415–20421.

- Singh, A.; Bains, D.; Hassen, W.M.; Singh, N.; Dubowski, J.J. Formation of a Au/Au9Ga4 Alloy Nanoshell on a Bacterial Surface through Galvanic Displacement Reaction for High-Contrast Imaging. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 477–485.

- Xiao, Q.; Mai, B.; Nie, Y.; Yuan, C.; Xiang, M.; Shi, Z.; Wu, J.; Leung, W.; Xu, C.; Yao, S.Q.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Demonstration of Ultraefficient and Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Agents for Photodynamic Antibacterial Chemotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 11588–11596.

- Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, L. Different Surface Interactions between Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers and Biological Targets. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 1211–1220.

- Ourari, A.; Ouari, K.; Moumeni, W.; Sibous, L.; Bouet, G.M.; Khan, M.A. Unsymmetrical Tetradentate Schiff Base Complexes Derived from 2,3-diaminophenol and Salicylaldehyde or 5-bromosalicylaldehyde. Transit. Met. Chem. 2006, 31, 169–175.

- Wu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.Z.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, Y.; Tan, C. Fluorescence Array-Based Sensing of Metal Ions Using Conjugated Polyelectrolytes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6882–6888.

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Gan, N.; Li, Q.; Cuan, J. Detection and removal of antibiotic tetracycline in water with a highly stable luminescent MOF. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 262, 137–143.

- Liu, M.-K.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Bao, D.-D.; Zhu, G.; Yang, G.-H.; Geng, J.-F.; Li, H.-T. Effective Removal of Tetracycline Antibiotics from Water using Hybrid Carbon Membranes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep43717.

- Daghrir, R.; Drogui, P. Tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2013, 11, 209–227.

- Malik, A.H.; Iyer, P.K. Conjugated Polyelectrolyte Based Sensitive Detection and Removal of Antibiotics Tetracycline from Water. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 4433–4439.

- Hammerer, F.; Poyer, F.; Fourmois, L.; Chen, S.; Garcia, G.; Teulade-Fichou, M.-P.; Maillard, P.; Mahuteau-Betzer, F. Mitochondria-targeted cationic porphyrin-triphenylamine hybrids for enhanced two-photon photodynamic therapy. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 107–118.

- Deng, W.; Wu, Q.; Sun, P.; Yuan, P.; Lu, X.; Fan, Q.; Huang, W. Zwitterionic diketopyrrolopyrrole for fluorescence/photoacoustic imaging guided photodynamic/photothermal therapy. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 2805–2812.

- Di Maria, F.; Lodola, F.; Zucchetti, E.; Benfenati, F.; Lanzani, G. The evolution of artificial light actuators in living systems: From planar to nanostructured interfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 4757–4780.

- Simelane, N.W.N.; Kruger, C.A.; Abrahamse, H. Targeted Nanoparticle Photodynamic Diagnosis and Therapy of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9779.

- Simelane, N.W.N.; Kruger, C.A.; Abrahamse, H. Photodynamic diagnosis and photodynamic therapy of colorectal cancer in vitro and in vivo. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41560–41576.

- Lan, M.; Zhao, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, J.; Guo, L.; Niu, G.; Li, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Water-Soluble Polythiophene for Two-Photon Excitation Fluorescence Imaging and Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 14590–14595.

More

Information

Subjects:

Polymer Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

3.3K

Entry Collection:

Organic Synthesis

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No