| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cortney Steele | + 2290 word(s) | 2290 | 2022-03-08 05:04:34 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2290 | 2022-03-17 05:04:11 | | |

Video Upload Options

Obesity indirectly causes strain on the kidneys by increasing blood pressure, intensifying renal tubular sodium reabsorption, and weakening pressure natriuresis. These events lead to volume expansion by stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Physical compression of the kidneys from surplus visceral adipose tissue also impacts kidney health and function. Obesity also can lead to renal vasodilation and glomerular hyperfiltration that initially serve as compensatory mechanisms to maintain a sodium balance in the face of increased tubular reabsorption. These potential mechanisms may make obesity a risk for the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD).

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiological Data on BMI and Kidney Disease

2.1. General Population

2.2. Chronic Kidney Disease

2.3. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

3. Potential Role of Adipose Tissue

3.1. Types and Distribution of Adipose Tissue

3.2. Harmful Effects of Adipose Tissue

References

- Fruh, S.M. Obesity: Risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long-term weight management. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, S3–S14.

- Hruby, A.; Hu, F.B. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 673–689.

- Stevens, G.A.; Singh, G.M.; Lu, Y.; Danaei, G.; Lin, J.K.; Finucane, M.M.; Bahalim, A.N.; McIntire, R.K.; Gutierrez, H.R.; Cowan, M.; et al. National, regional, and global trends in adult overweight and obesity prevalences. Popul. Health Metr. 2012, 10, 22.

- Baskin, M.L.; Ard, J.; Franklin, F.; Allison, D.B. Prevalence of obesity in the United States. Obes. Rev. 2005, 6, 5–7.

- Flegal, K.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Ogden, C.L.; Curtin, L.R. Prevalence and Trends in Obesity Among US Adults, 1999–2008. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2010, 303, 235–241.

- Valderas, J.M.; Starfield, B.; Sibbald, B.; Salisbury, C.; Roland, M. Defining comorbidity: Implications for understanding health and health services. Ann. Fam. Med. 2009, 7, 357–363.

- Chalmers, L.; Kaskel, F.J.; Bamgbola, O. The Role of Obesity and Its Bioclinical Correlates in the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2006, 13, 352–364.

- Hall, J.E.; Brands, M.W.; Dixon, W.N.; Smith, M.J., Jr. Obesity-induced hypertension. Renal function and systemic hemodynamics. Hypertension 1993, 22, 292–299.

- Hall, J.E.; Crook, E.D.; Jones, D.W.; Wofford, M.R.; Dubbert, P.M. Mechanisms of obesity-associated cardiovascular and renal disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2002, 324, 127–137.

- Vaes, B.; Beke, E.; Truyers, C.; Elli, S.; Buntinx, F.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Goderis, G.; Van Pottelbergh, G. The correlation between blood pressure and kidney function decline in older people: A registry-based cohort study. British Med. J. Open. 2015, 5, e007571.

- Hall, M.E.; do Carmo, J.M.; da Silva, A.A.; Juncos, L.A.; Wang, Z.; Hall, J.E. Obesity, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2014, 7, 75–88.

- Alvarez, G.E.; Beske, S.D.; Ballard, T.P.; Davy, K.P. Sympathetic Neural Activation in Visceral Obesity. Circ. 2002, 106, 2533–2536.

- Esler, M.; Rumantir, M.; Wiesner, G.; Kaye, D.; Hastings, J.; Lambert, G. Sympathetic nervous system and insulin resistance: From obesity to diabetes. Am. J. Hypertens. 2001, 14, 304S–309S.

- Abate, N.I.; Mansour, Y.H.; Tuncel, M.; Arbique, D.; Chavoshan, B.; Kizilbash, A.; Howell-Stampley, T.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Victor, R.G. Overweight and sympathetic overactivity in black Americans. Hypertens. 2001, 38, 379–383.

- Bloomfield, G.L.; Sugerman, H.J.; Blocher, C.R.; Gehr, T.W.; Sica, D.A. Chronically increased intra-abdominal pressure produces systemic hypertension in dogs. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2000, 24, 819–824.

- Dwyer, T.M.; Banks, S.A.; Alonso-Galicia, M.; Cockrell, K.; Carroll, J.F.; Bigler, S.A.; Hall, J.E. Distribution of renal medullary hyaluronan in lean and obese rabbits. Kidney Int. 2000, 58, 721–729.

- Hall, J.E.; Henegar, J.R.; Dwyer, T.M.; Liu, J.; da Silva, A.A.; Kuo, J.J.; Tallam, L. Is obesity a major cause of chronic kidney disease? Adv. Ren. Replace. Ther. 2004, 11, 41–54.

- Fox, C.S.; Larson, M.G.; Leip, E.P.; Culleton, B.; Wilson, P.W.; Levy, D. Predictors of new-onset kidney disease in a community-based population. J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 2004, 291, 844–850.

- Iseki, K.; Ikemiya, Y.; Kinjo, K.; Inoue, T.; Iseki, C.; Takishita, S. Body mass index and the risk of development of end-stage renal disease in a screened cohort. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 1870–1876.

- Hsu, C.Y.; McCulloch, C.E.; Iribarren, C.; Darbinian, J.; Go, A.S. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 21–28.

- Tanner, R.M.; Brown, T.M.; Muntner, P. Epidemiology of Obesity, the Metabolic Syndrome, and Chronic Kidney Disease. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2012, 14, 152–159.

- Kramer, H.J.; Saranathan, A.; Luke, A.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Guichan, C.; Hou, S.; Cooper, R. Increasing body mass index and obesity in the incident ESRD population. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 1453–1459.

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chan, S.; Cameron, A.; Healy, H.G.; Venuthurupalli, S.K.; Tan, K.-S.; Hoy, W.E. BMI and its association with death and the initiation of renal replacement therapy (RRT) in a cohort of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 329.

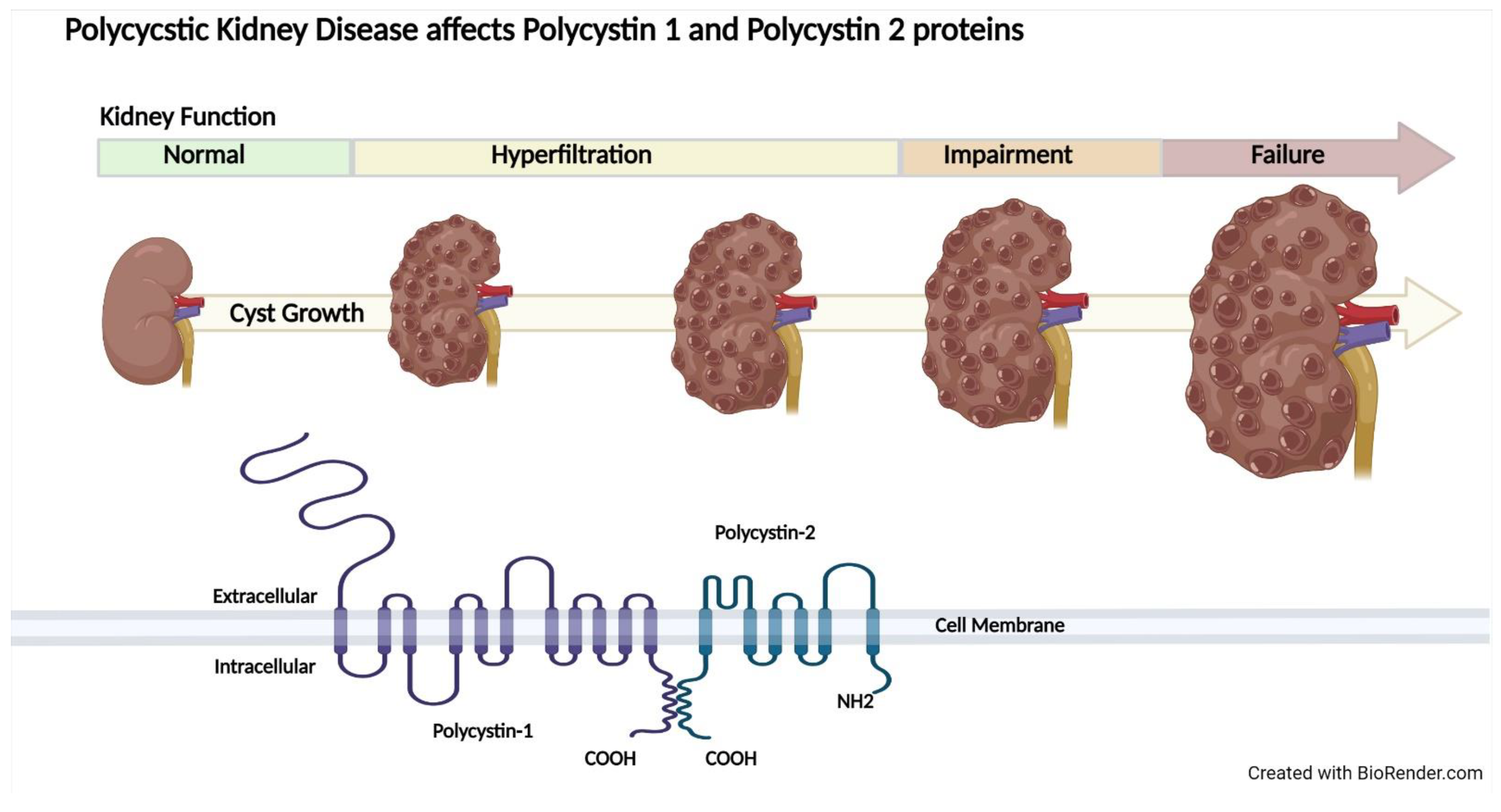

- Bergmann, C.; Guay-Woodford, L.M.; Harris, P.C.; Horie, S.; Peters, D.J.M.; Torres, V.E. Polycystic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2018, 4, 50.

- Cornec-Le Gall, E.; Alam, A.; Perrone, R.D. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet 2019, 393, 919–935.

- Schrier, R.W.; Abebe, K.Z.; Perrone, R.D.; Torres, V.E.; Braun, W.E.; Steinman, T.I.; Winklhofer, F.T.; Brosnahan, G.; Czarnecki, P.G.; Hogan, M.C.; et al. Blood Pressure in Early Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2255–2266.

- Nowak, K.L.; Steele, C.; Gitomer, B.; Wang, W.; Ouyang, J.; Chonchol, M.B. Overweight and Obesity and Progression of ADPKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 908–915.

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Caballero, B.; Cheskin, L.J. Association between obesity and kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2008, 73, 19–33.

- Pinto-Sietsma, S.-J.; Navis, G.; Janssen, W.M.T.; de Zeeuw, D.; Gans, R.O.B.; de Jong, P.E. A central body fat distribution is related to renal function impairment, even in lean subjects. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 41, 733–741.

- Chang, A.; Van Horn, L.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Liu, K.; Muntner, P.; Newsome, B.; Shoham, D.A.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Reis, J.; et al. Lifestyle-related factors, obesity, and incident microalbuminuria: The CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2013, 62, 267–275.

- Thoenes, M.; Reil, J.C.; Khan, B.V.; Bramlage, P.; Volpe, M.; Kirch, W.; Böhm, M. Abdominal obesity is associated with microalbuminuria and an elevated cardiovascular risk profile in patients with hypertension. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 577–585.

- Foster, M.C.; Hwang, S.J.; Massaro, J.M.; Hoffmann, U.; DeBoer, I.H.; Robins, S.J.; Vasan, R.S.; Fox, C.S. Association of subcutaneous and visceral adiposity with albuminuria: The Framingham Heart Study. Obesity 2011, 19, 1284–1289.

- Gelber, R.P.; Kurth, T.; Kausz, A.T.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; Levey, A.S.; Gaziano, J.M. Association between body mass index and CKD in apparently healthy men. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 46, 871–880.

- Kramer, H.; Luke, A.; Bidani, A.; Cao, G.; Cooper, R.; McGee, D. Obesity and prevalent and incident CKD: The Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 46, 587–594.

- de Boer, I.H.; Katz, R.; Fried, L.F.; Ix, J.H.; Luchsinger, J.; Sarnak, M.J.; Shlipak, M.G.; Siscovick, D.S.; Kestenbaum, B. Obesity and change in estimated GFR among older adults. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 54, 1043–1051.

- Lu, J.L.; Molnar, M.Z.; Naseer, A.; Mikkelsen, M.K.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kovesdy, C.P. Association of age and BMI with kidney function and mortality: A cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 704–714.

- Vivante, A.; Golan, E.; Tzur, D.; Leiba, A.; Tirosh, A.; Skorecki, K.; Calderon-Margalit, R. Body mass index in 1.2 million adolescents and risk for end-stage renal disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 2012, 172, 1644–1650.

- Bray, G.A. Overweight is risking fate. Definition, classification, prevalence, and risks. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1987, 499, 14–28.

- Chang, T.-J.; Zheng, C.-M.; Wu, M.-Y.; Chen, T.-T.; Wu, Y.-C.; Wu, Y.-L.; Lin, H.-T.; Zheng, J.-Q.; Chu, N.-F.; Lin, Y.-M.; et al. Relationship between body mass index and renal function deterioration among the Taiwanese chronic kidney disease population. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6908.

- Herrington, W.G.; Smith, M.; Bankhead, C.; Matsushita, K.; Stevens, S.; Holt, T.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Coresh, J.; Woodward, M. Body-mass index and risk of advanced chronic kidney disease: Prospective analyses from a primary care cohort of 1.4 million adults in England. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173515.

- Iseki, K. Body mass index and the risk of chronic renal failure: The Asian experience. Contrib. Nephrol. 2006, 151, 42–56.

- Shankar, A.; Leng, C.; Chia, K.S.; Koh, D.; Tai, E.S.; Saw, S.M.; Lim, S.C.; Wong, T.Y. Association between body mass index and chronic kidney disease in men and women: Population-based study of Malay adults in Singapore. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 1910–1918.

- Horber, F.F.; Gruber, B.; Thomi, F.; Jensen, E.X.; Jaeger, P. Effect of sex and age on bone mass, body composition and fuel metabolism in humans. Nutrition 1997, 13, 524–534.

- Kuk, J.L.; Lee, S.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Ross, R. Waist circumference and abdominal adipose tissue distribution: Influence of age and sex. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 1330–1334.

- Othman, M.; Kawar, B.; El Nahas, A.M. Influence of obesity on progression of non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: A retrospective cohort study. Nephron. Clin. Pract. 2009, 113, c16–c23.

- MacLaughlin, H.L.; Pike, M.; Selby, N.M.; Siew, E.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Guide, A.; Stewart, T.G.; Himmelfarb, J.; Go, A.S.; Parikh, C.R.; et al. Body mass index and chronic kidney disease outcomes after acute kidney injury: A prospective matched cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 200.

- Khedr, A.; Khedr, E.; House, A.A. Body mass index and the risk of progression of chronic kidney disease. J. Ren. Nutr. 2011, 21, 455–461.

- Mohsen, A.; Brown, R.; Hoefield, R.; Kalra, P.A.; O’Donoghue, D.; Middleton, R.; New, D. Body mass index has no effect on rate of progression of chronic kidney disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Nephrol. 2012, 25, 384–393.

- Brown, R.N.K.L.; Mohsen, A.; Green, D.; Hoefield, R.A.; Summers, L.K.M.; Middleton, R.J.; O’Donoghue, D.J.; Kalra, P.A.; New, D.I. Body mass index has no effect on rate of progression of chronic kidney disease in non-diabetic subjects. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27, 2776–2780.

- Lowrie, E.G.; Lew, N.L. Death risk in hemodialysis patients: The predictive value of commonly measured variables and an evaluation of death rate differences between facilities. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1990, 15, 458–482.

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Block, G.; Humphreys, M.H.; Kopple, J.D. Reverse epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in maintenance dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 793–808.

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Block, G.; Horwich, T.; Fonarow, G.C. Reverse epidemiology of conventional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 1439–1444.

- Leavey, S.F.; McCullough, K.; Hecking, E.; Goodkin, D.; Port, F.K.; Young, E.W. Body mass index and mortality in ‘healthier’ as compared with ‘sicker’ haemodialysis patients: Results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2001, 16, 2386–2394.

- Molnar, M.Z.; Streja, E.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Bunnapradist, S.; Sampaio, M.S.; Jing, J.; Krishnan, M.; Nissenson, A.R.; Danovitch, G.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Associations of body mass index and weight loss with mortality in transplant-waitlisted maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Transplant. 2011, 11, 725–736.

- Horwich, T.B.; Fonarow, G.C.; Hamilton, M.A.; MacLellan, W.R.; Woo, M.A.; Tillisch, J.H. The relationship between obesity and mortality in patients with heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 38, 789–795.

- Fung, F.; Sherrard, D.J.; Gillen, D.L.; Wong, C.; Kestenbaum, B.; Seliger, S.; Ball, A.; Stehman-Breen, C. Increased risk for cardiovascular mortality among malnourished end-stage renal disease patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002, 40, 307–314.

- Lee, M.J.; Park, J.T.; Park, K.S.; Kwon, Y.E.; Han, S.H.; Kang, S.-W.; Choi, K.H.; Oh, K.-H.; Park, S.K.; Chae, D.W.; et al. Normal body mass index with central obesity has increased risk of coronary artery calcification in Korean patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 1368–1376.

- Grantham, J.J.; Torres, V.E.; Chapman, A.B.; Guay-Woodford, L.M.; Bae, K.T.; King, B.F.; Wetzel, L.H.; Baumgarten, D.A.; Kenney, P.J.; Harris, P.C.; et al. Volume Progression in Polycystic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 2122–2130.

- Irazabal, M.V.; Rangel, L.J.; Bergstralh, E.J.; Osborn, S.L.; Harmon, A.J.; Sundsbak, J.L.; Bae, K.T.; Chapman, A.B.; Grantham, J.J.; Mrug, M.; et al. Imaging Classification of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: A Simple Model for Selecting Patients for Clinical Trials. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 160–172.

- Torres, V.E.; Chapman, A.B.; Perrone, R.D.; Bae, K.T.; Abebe, K.Z.; Bost, J.E.; Miskulin, D.C.; Steinman, T.I.; Braun, W.E.; Winklhofer, F.T.; et al. Analysis of baseline parameters in the HALT polycystic kidney disease trials. Kidney Int. 2012, 81, 577–585.

- Nowak, K.L.; You, Z.; Gitomer, B.; Brosnahan, G.; Torres, V.E.; Chapman, A.B.; Perrone, R.D.; Steinman, T.I.; Abebe, K.Z.; Rahbari-Oskoui, F.F.; et al. Overweight and Obesity Are Predictors of Progression in Early Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 571–578.

- Freise, J.; Tavakol, M.; Gao, Y.; Klein, O.; Lee, B.K.; Freise, C.; Park, M. The Effect of Enlarged Kidneys on Calculated Body Mass Index Categorization in Transplant Recipients With ADPKD. Kidney Int. Rep. 2019, 4, 606–609.

- Barberio, A.M.; Alareeki, A.; Viner, B.; Pader, J.; Vena, J.E.; Arora, P.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Brenner, D.R. Central body fatness is a stronger predictor of cancer risk than overall body size. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 383.

- Pi-Sunyer, F.X. The epidemiology of central fat distribution in relation to disease. Nutr. Rev. 2004, 62, S120–S126.

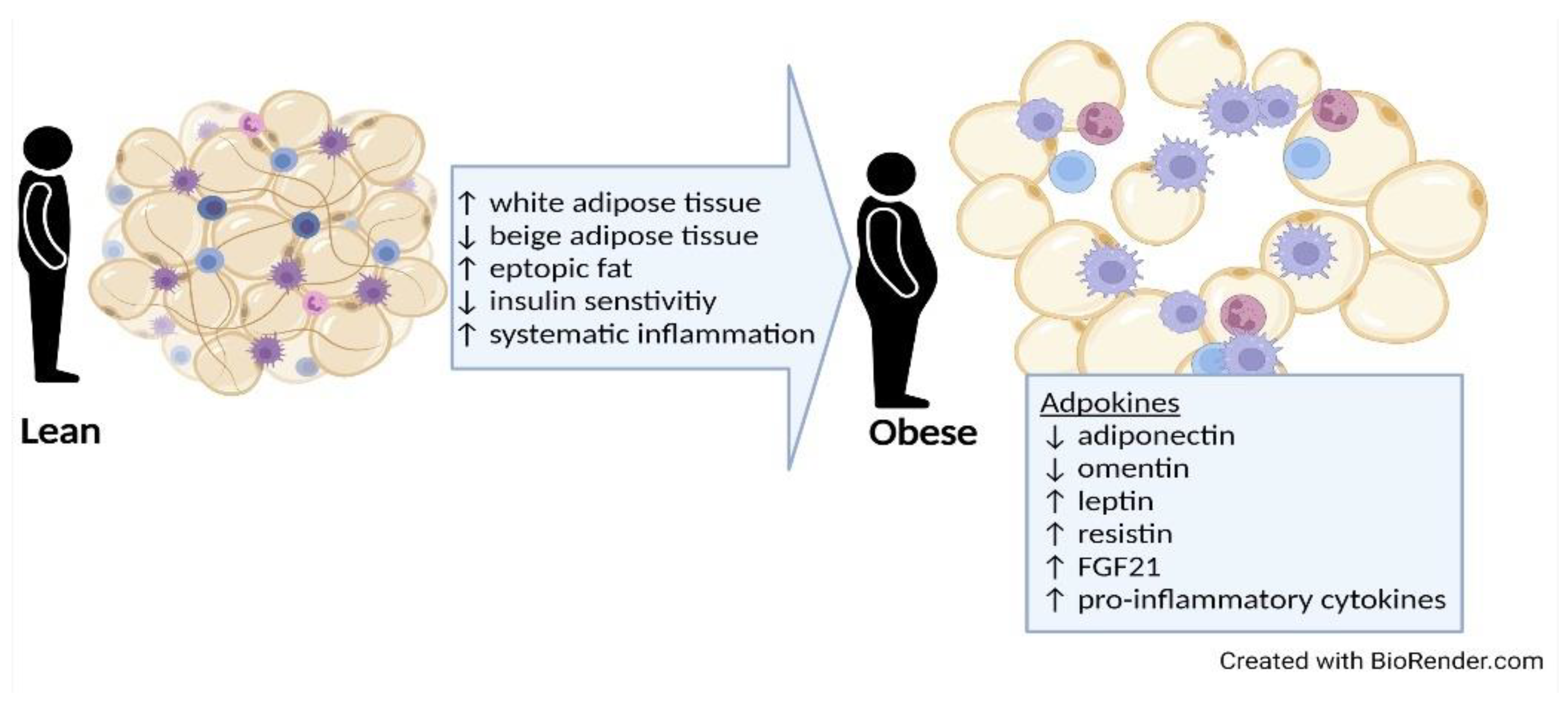

- Choe, S.S.; Huh, J.Y.; Hwang, I.J.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, J.B. Adipose Tissue Remodeling: Its Role in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 2016, 7, 30.

- Chait, A.; den Hartigh, L.J. Adipose Tissue Distribution, Inflammation and Its Metabolic Consequences, Including Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 22.

- Nowak, K.L.; Hopp, K. Metabolic Reprogramming in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: Evidence and Therapeutic Potential. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 577–584.

- Shuster, A.; Patlas, M.; Pinthus, J.H.; Mourtzakis, M. The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: A critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. Br. J. Radiol. 2012, 85, 1–10.

- Burhans, M.S.; Hagman, D.K.; Kuzma, J.N.; Schmidt, K.A.; Kratz, M. Contribution of Adipose Tissue Inflammation to the Development of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1–58.

- Young, J.A.; Hwang, S.-J.; Sarnak, M.J.; Hoffmann, U.; Massaro, J.M.; Levy, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Larson, M.G.; Vasan, R.S.; O’Donnell, C.J.; et al. Association of visceral and subcutaneous adiposity with kidney function. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2008, 3, 1786–1791.

- Reddy, P.; Lent-Schochet, D.; Ramakrishnan, N.; McLaughlin, M.; Jialal, I. Metabolic syndrome is an inflammatory disorder: A conspiracy between adipose tissue and phagocytes. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 496, 35–44.

- Kahn, C.R.; Wang, G.; Lee, K.Y. Altered adipose tissue and adipocyte function in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 3990–4000.

- Zhang, Y.; Hao, J.; Tarrago, M.G.; Warner, G.M.; Giorgadze, N.; Wei, Q.; Huang, Y.; He, K.; Chen, C.; Peclat, T.R.; et al. FBF1 deficiency promotes beiging and healthy expansion of white adipose tissue. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109481.

- Reyes-Farias, M.; Fos-Domenech, J.; Serra, D.; Herrero, L.; Sánchez-Infantes, D. White adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity and aging. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 192, 114723.

- Okhunov, Z.; Mues, A.C.; Kline, M.; Haramis, G.; Xu, B.; Mirabile, G.; Vira, M.; Landman, J. Evaluation of perirenal fat as a predictor of cT 1a renal cortical neoplasm histopathology and surgical outcomes. J. Endourol. 2012, 26, 911–916.

- Foster, M.C.; Hwang, S.J.; Porter, S.A.; Massaro, J.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Fox, C.S. Fatty kidney, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease: The Framingham Heart Study. Hypertens 2011, 58, 784–790.

- Wei, G.; Sun, H.; Dong, K.; Hu, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhuang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shao, Y.; Tang, H.; et al. The thermogenic activity of adjacent adipocytes fuels the progression of ccRCC and compromises anti-tumor therapeutic efficacy. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2021–2039.e8.

- Ahima, R.S.; Lazar, M.A. Adipokines and the peripheral and neural control of energy balance. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 1023–1031.

- Considine, R.V.; Sinha, M.K.; Heiman, M.L.; Kriauciunas, A.; Stephens, T.W.; Nyce, M.R.; Ohannesian, J.P.; Marco, C.C.; McKee, L.J.; Bauer, T.L.; et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 292–295.

- de Souza Batista, C.M.; Yang, R.Z.; Lee, M.J.; Glynn, N.M.; Yu, D.Z.; Pray, J.; Ndubuizu, K.; Patil, S.; Schwartz, A.; Kligman, M.; et al. Omentin plasma levels and gene expression are decreased in obesity. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1655–1661.

- Samaras, K.; Botelho, N.K.; Chisholm, D.J.; Lord, R.V. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue gene expression of serum adipokines that predict type 2 diabetes. Obesity 2010, 18, 884–889.

- Degawa-Yamauchi, M.; Bovenkerk, J.E.; Juliar, B.E.; Watson, W.; Kerr, K.; Jones, R.; Zhu, Q.; Considine, R.V. Serum resistin (FIZZ3) protein is increased in obese humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 5452–5455.

- McTernan, P.G.; McTernan, C.L.; Chetty, R.; Jenner, K.; Fisher, F.M.; Lauer, M.N.; Crocker, J.; Barnett, A.H.; Kumar, S. Increased resistin gene and protein expression in human abdominal adipose tissue. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 2407–2410.

- Zhang, X.; Yeung, D.C.; Karpisek, M.; Stejskal, D.; Zhou, Z.G.; Liu, F.; Wong, R.L.; Chow, W.S.; Tso, A.W.; Lam, K.S.; et al. Serum FGF21 levels are increased in obesity and are independently associated with the metabolic syndrome in humans. Diabetes. 2008, 57, 1246–1253.

- Bastard, J.P.; Jardel, C.; Bruckert, E.; Blondy, P.; Capeau, J.; Laville, M.; Vidal, H.; Hainque, B. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 3338–3342.

- Pickup, J.C.; Chusney, G.D.; Thomas, S.M.; Burt, D. Plasma interleukin-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha and blood cytokine production in type 2 diabetes. Life Sci. 2000, 67, 291–300.

- Christiansen, T.; Richelsen, B.; Bruun, J.M. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is produced in isolated adipocytes, associated with adiposity and reduced after weight loss in morbid obese subjects. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 146–150.

- Yang, R.Z.; Lee, M.J.; Hu, H.; Pollin, T.I.; Ryan, A.S.; Nicklas, B.J.; Snitker, S.; Horenstein, R.B.; Hull, K.; Goldberg, N.H.; et al. Acute-phase serum amyloid A: An inflammatory adipokine and potential link between obesity and its metabolic complications. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e287.

- Sag, S.; Yildiz, A.; Gullulu, S.; Gungoren, F.; Ozdemir, B.; Cegilli, E.; Oruc, A.; Ersoy, A.; Gullulu, M. Early atherosclerosis in normotensive patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: The relation between epicardial adipose tissue thickness and carotid intima-media thickness. Springerplus. 2016, 5, 211.