| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sergio Bydlowski | + 1139 word(s) | 1139 | 2022-01-30 03:19:41 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | + 135 word(s) | 1274 | 2022-03-15 02:14:14 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | + 1654 word(s) | 2793 | 2022-03-15 02:23:01 | | |

Video Upload Options

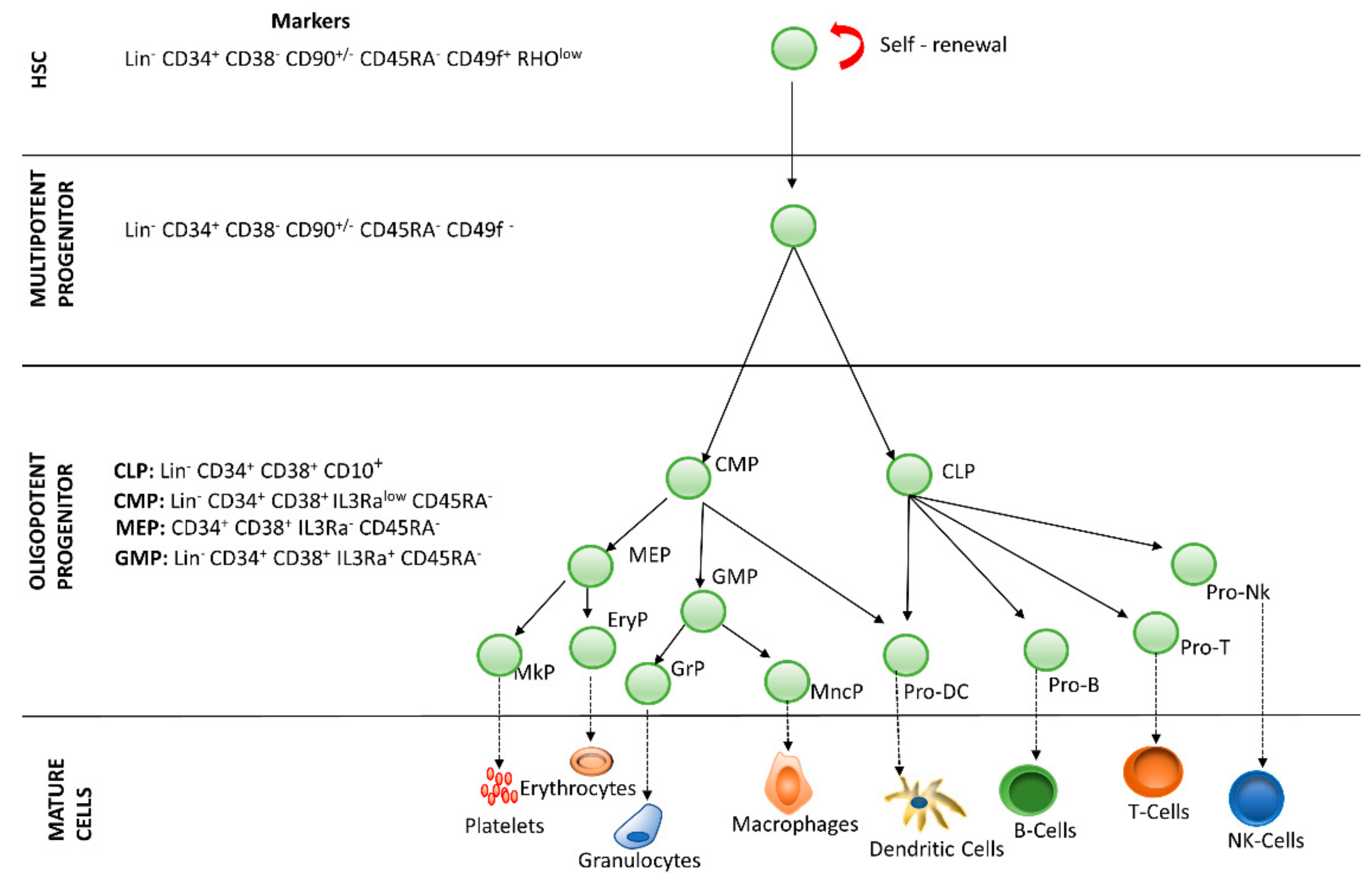

Blood is a connective tissue made up of approximately 34% cells and 66% plasma, transporting nutrients, gases and molecules in general to the whole body. Hematopoiesis is the main function of bone marrow. Human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells reside in the bone marrow microenvironment, making it a hotspot for the development of hematopoietic diseases. Numerous alterations that correspond to disease progression have been identified in the bone marrow stem cell niche. Complex interactions between the bone marrow microenvironment and hematopoietic stem cells determine the balance between the proliferation, differentiation and homeostasis of the stem cell compartment. Changes in this tightly regulated network can provoke malignant transformation. However, our understanding of human hematopoiesis and the associated niche biology remains limited due to accessibility to human material and the limits of in vitro culture models. Traditional culture systems for human hematopoietic studies lack microenvironment niches, spatial marrow gradients, and dense cellularity, rendering them incapable of effectively translating marrow physiology ex vivo.

1. Introduction

2. Hematopoietic Stem Cells

3. 3D Hematopoietic Stem Cell Culture

References

- Ng, A.P.; Alexander, W.S. Haematopoietic stem cells: Past, present and future. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17002.

- Chotinantakul, K.; Leeanansaksiri, W. Hematopoietic stem cell development, niches, and signaling pathways. Bone Marrow Res. 2012, 2012, 270425.

- Wasnik, S.; Tiwari, A.; Kirkland, M.A.; Pande, G. Osteohematopoietic stem cell niches in bone marrow. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2012, 298, 95–133.

- Bianco, P.; Robey, P.G. Stem cells in tissue engineering. Nature 2001, 414, 118–121.

- Calvi, L.M.; Link, D.C. Cellular complexity of the bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell niche. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2014, 94, 112–124.

- Nilsson, S.K.; Johnston, H.M.; Coverdale, J.A. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: Inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood 2001, 97, 2293–2299.

- Kiel, M.J.; Morrison, S.J. Maintaining hematopoietic stem cells in the vascular niche. Immunity 2006, 25, 862–864.

- Orkin, S.H.; Zon, L.I. Hematopoiesis: An evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell 2008, 132, 631–644.

- Calvi, L.M.; Adams, G.B.; Weibrecht, K.W.; Weber, J.M.; Olson, D.P.; Knight, M.C.; Martin, R.P.; Schipani, E.; Divieti, P.; Bringhurst, F.R.; et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature 2003, 425, 841–846.

- Oh, I.H.; Kwon, K.R. Concise review: Multiple niches for hematopoietic stem cell regulations. Stem Cells 2010, 28, 1243–1249.

- Crane, G.M.; Jeffery, E.; Morrison, S.J. Adult haematopoietic stem cell niches. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 573–590.

- Nies, C.; Gottwald, E. Advances in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine Artificial Hematopoietic Stem Cell Niches-Dimensionality Matters. Adv. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 2, 42.

- Gomariz, A.; Isringhausen, S.; Helbling, P.M.; Nombela-Arrieta, C. Imaging and spatial analysis of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019.

- Blank, U.; Karlsson, G.; Karlsson, S. Signaling pathways governing stem-cell fate. Blood 2008, 111, 492–503.

- Majka, M.; Janowska-Wieczorek, A.; Ratajczak, J.; Ehrenman, K.; Pietrzkowski, Z.; Kowalska, M.A.; Gewirtz, A.M.; Emerson, S.G.; Ratajczak, M.Z. Numerous growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines are secreted by human CD34(+) cells, myeloblasts, erythroblasts, and megakaryoblasts and regulate normal hematopoiesis in an autocrine/paracrine manner. Blood 2001, 97, 3075–3085.

- Jafari, M.; Ghadami, E.; Dadkhah, T.; Akhavan-Niaki, H. PI3k/AKT signaling pathway: Erythropoiesis and beyond. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 2373–2385.

- Cerdan, C.; Bhatia, M. Novel roles for Notch, Wnt and Hedgehog in hematopoesis derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2010, 54, 955–963.

- Aster, J.C.; Pear, W.S.; Blacklow, S.C. Notch signaling in leukemia. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2008, 3, 587–613.

- Tekmal, R.R.; Keshava, N. Role of MMTV integration locus cellular genes in breast cancer. Front. Biosci. 1997, 2, 519–526.

- Duncan, A.W.; Rattis, F.M.; DiMascio, L.N.; Congdon, K.L.; Pazianos, G.; Zhao, C.; Pazianos, G.; Zhao, C.; Yoon, K.; Cook, J.M.; et al. Integration of Notch and Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cell maintenance. Nat Immunol. 2005, 6, 314–322.

- Gordon, M.D.; Nusse, R. Wnt signaling: Multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 22429–22433.

- Dyer, M.A.; Farrington, S.M.; Mohn, D.; Munday, J.R.; Baron, M.H. Indian hedgehog activates hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis and can respecify prospective neurectodermal cell fate in the mouse embryo. Development 2001, 128, 1717–1730.

- Shi, X.; Wei, S.; Simms, K.J.; Cumpston, D.N.; Ewing, T.J.; Zhang, P. Sonic Hedgehog Signaling Regulates Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cell Activation during the Granulopoietic Response to Systemic Bacterial Infection. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 349.

- Mendez-Ferrer, S.; Michurina, T.V.; Ferraro, F.; Mazloom, A.R.; Macarthur, B.D.; Lira, S.A.; Scadden, D.T.; Ma’ayan, A.; Enikolopov, G.N.; Frenette, P.S. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature 2010, 466, 829–834.

- McNiece, I.K.; Briddell, R.A. Stem cell factor. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995, 58, 14–22.

- Edling, C.E.; Hallberg, B. c-Kit--a hematopoietic cell essential receptor tyrosine kinase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 1995–1998.

- Nakamura-Ishizu, A.; Takizawa, H.; Suda, T. The analysis, roles and regulation of quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Development 2014, 141, 4656–4666.

- Ravi, M.; Paramesh, V.; Kaviya, S.R.; Anuradha, E.; Solomon, F.D. 3D cell culture systems: Advantages and applications. J. Cell Physiol. 2015, 230, 16–26.

- Murray-Dunning, C.; McArthur, S.L.; Sun, T.; McKean, R.; Ryan, A.J.; Haycock, J.W. Three-dimensional alignment of schwann cells using hydrolysable microfiber scaffolds: Strategies for peripheral nerve repair. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 695, 155–166.

- Tee, D.E.H. Culture of Animal Cells: A Manual of Basic Technique. J. R. Soc. Med. 1984, 77, 902–903.

- Melissinaki, V.; Gill, A.A.; Ortega, I.; Vamvakaki, M.; Ranella, A.; Haycock, J.W.; Fotakis, C.; Farsari, M.; Claeyssens, F. Direct laser writing of 3D scaffolds for neural tissue engineering applications. Biofabrication 2011, 3, 045005.

- Whitesides, G.M. The origins and the future of microfluidics. Nature 2006, 442, 368–373.

- Mehling, M.; Tay, S. Microfluidic cell culture. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 25, 95–102.

- El-Ali, J.; Sorger, P.K.; Jensen, K.F. Cells on chips. Nature 2006, 442, 403–411.

- Dittrich, P.S.; Manz, A. Lab-on-a-chip: Microfluidics in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 210–218.

- Pampaloni, F.; Reynaud, E.G.; Stelzer, E.H. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 839–845.

- Haycock, J.W. 3D cell culture: A review of current approaches and techniques. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 695, 1–15.

- Toda, S.; Watanabe, K.; Yokoi, F.; Matsumura, S.; Suzuki, K.; Ootani, A.; Aoki, S.; Koike, N.; Sugihara, H. A new organotypic culture of thyroid tissue maintains three-dimensional follicles with C cells for a long term. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 294, 906–911.

- Lancaster, M.A.; Huch, M. Disease modelling in human organoids. Dis. Model Mech. 2019, 12.

- Lancaster, M.A.; Knoblich, J.A. Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies. Science 2014, 345, 1247125.

- Seet, C.S.; He, C.; Bethune, M.T.; Li, S.; Chick, B.; Gschweng, E.H.; Zhu, Y.; Kim, K.; Kohn, D.B.; Baltimore, D.; et al. Generation of mature T cells from human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in artificial thymic organoids. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 521–530.

- Yuhas, J.M.; Li, A.P.; Martinez, A.O.; Ladman, A.J. A simplified method for production and growth of multicellular tumor spheroids. Cancer Res. 1977, 37, 3639–3643.

- Fennema, E.; Rivron, N.; Rouwkema, J.; van Blitterswijk, C.; de Boer, J. Spheroid culture as a tool for creating 3D complex tissues. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 108–115.

- Tanner, K.; Gottesman, M.M. Beyond 3D culture models of cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 283ps9.

- Gillet, J.P.; Calcagno, A.M.; Varma, S.; Marino, M.; Green, L.J.; Vora, M.I.; Patel, C.; Orina, J.N.; Eliseeva, T.A.; Singal, V.; et al. Redefining the relevance of established cancer cell lines to the study of mechanisms of clinical anti-cancer drug resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18708–18713.

- Li, Y.; Huang, G.; Li, M.; Wang, L.; Elson, E.L.; Jian Lu, T.; Genin, G.M.; Xu, F. An approach to quantifying 3D responses of cells to extreme strain. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19550.

- Polymeric Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering Application: A Review. Int. J. Polymer Sci. 2011, 2011.

- Kleinman, H.K.; Philp, D.; Hoffman, M.P. Role of the extracellular matrix in morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003, 14, 526–532.

- Raic, A.; Naolou, T.; Mohra, A.; Chatterjee, C.; Lee-Thedieck, C. 3D models of the bone marrow in health and disease: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. MRS Commun. 2019, 9, 37–52.

- Llames, S.; Garcia, E.; Otero Hernandez, J.; Meana, A. Tissue bioengineering and artificial organs. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 741, 314–336.

- Futrega, K.; Atkinson, K.; Lott, W.B.; Doran, M.R. Spheroid Coculture of Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells and Monolayer Expanded Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in Polydimethylsiloxane Microwells Modestly Improves In Vitro Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cell Expansion. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods. 2017, 23, 200–218.

- Leisten, I.; Kramann, R.; Ventura Ferreira, M.S.; Bovi, M.; Neuss, S.; Ziegler, P.; Wagner, W.; Knüchel, R.; Schneider, R.K. 3D co-culture of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells in collagen scaffolds as a model of the hematopoietic niche. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 1736–1747.

- Rodling, L.; Schwedhelm, I.; Kraus, S.; Bieback, K.; Hansmann, J.; Lee-Thedieck, C. 3D models of the hematopoietic stem cell niche under steady-state and active conditions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4625.

- Reticker-Flynn, N.E.; Malta, D.F.; Winslow, M.M.; Lamar, J.M.; Xu, M.J.; Underhill, G.H.; Hynes, R.O.; Jacks, T.E.; Bhatia, S.N. A combinatorial extracellular matrix platform identifies cell-extracellular matrix interactions that correlate with metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1122.

- Chen, Y.; Gao, D.; Wang, Y.; Lin, S.; Jiang, Y. A novel 3D breast-cancer-on-chip platform for therapeutic evaluation of drug delivery systems. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1036, 97–106.

- Song, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, R.; Chen, G.; Liu, L. Microfabrication-Based Three-Dimensional (3-D) Extracellular Matrix Microenvironments for Cancer and Other Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 935.

- Wu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, A.; He, H.; He, C.; Shuai, X.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Ren, B.; Zheng, J.; et al. Sulfated zwitterionic poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) hydrogels promote complete skin regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2018, 71, 293–305.

- Yi, H.G.; Lee, H.; Cho, D.W. 3D Printing of Organs-On-Chips. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 10.

- Ozbolat, I.T. Bioprinting scale-up tissue and organ constructs for transplantation. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 395–400.

- Novo, P.; Volpetti, F.; Chu, V.; Conde, J.P. Control of sequential fluid delivery in a fully autonomous capillary microfluidic device. Lab. Chip. 2013, 13, 641–645.

- Ong, S.M.; Zhang, C.; Toh, Y.C.; Kim, S.H.; Foo, H.L.; Tan, C.H.; van Noort, D.; Park, S.; Yu, H. A gel-free 3D microfluidic cell culture system. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3237–3244.

- Zhang, Y.S.; Duchamp, M.; Oklu, R.; Ellisen, l.W.; Langer, R.; Khademhosseini, A. Bioprinting the Cancer Microenvironment. ACS Biomater Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1710–1721.

- Shafiee, A.; Atala, A. Printing Technologies for Medical Applications. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 254–265.

- Torisawa, Y.S.; Spina, C.S.; Mammoto, T.; Mammoto, A.; Weaver, J.C.; Tat, T.; Collins, J.J.; Ingber, D.E. Bone marrow-on-a-chip replicates hematopoietic niche physiology in vitro. Nat. Method. 2014, 11, 663–669.

- Di Maggio, N.; Piccinini, E.; Jaworski, M.; Trumpp, A.; Wendt, D.J.; Martin, I. Toward modeling the bone marrow niche using scaffold-based 3D culture systems. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 321–329.