Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lucio Cappelli | + 1630 word(s) | 1630 | 2022-01-19 04:24:46 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | -73 word(s) | 1557 | 2022-03-04 02:33:06 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Cappelli, L. Consumers’ Preference for Local Food. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20174 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Cappelli L. Consumers’ Preference for Local Food. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20174. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Cappelli, Lucio. "Consumers’ Preference for Local Food" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20174 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Cappelli, L. (2022, March 03). Consumers’ Preference for Local Food. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20174

Cappelli, Lucio. "Consumers’ Preference for Local Food." Encyclopedia. Web. 03 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

The discussion on local food has been gaining attention in recent years, but there is still a lack of clear understanding of the term ‘local food’ in the literature. The relationship between local food and sustainability issues is still unclear and has various connotations. The discordance leads to further discussions on whether buying local food should be considered a sustainable behavior and whether consumer preference for local food can be perceived as a sustainable practice.

local food

local food definition

sustainable lifestyle

1. Introduction

Improving the quality of life of the population and introducing sustainable practices into people’s daily life has appeared on the agenda of global society [1]. Access to healthy food and the introduction of sustainable nutrition practices are two important challenges today. The growing interest in sustainable practices and high-quality and healthy products is reflected in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): goal 2, ‘end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture’ [2]. Support of short food supply chains (SFSC) may be one of the solutions to achieve this goal. SFSCs are considered as drivers of sustainable development, as they increase sustainability in all its dimensions; they reduce economic uncertainties, ensure fairness and trust between consumers and producers, and minimize pollution [3]. SFSCs are often associated with the concept of ‘local food’ and ‘local food systems’ but the connection between these concepts remains unclear [3][4][5]. Furthermore, the factors influencing consumer preference towards local food have obtained limited attention among scholars [6].

The application of sustainable practices is important and beneficial for SFSC stakeholders: producers, buying organizations, local governments, and consumers. Indeed, local food has been promoted by governmental and civil society organizations for decades [7]. Raising awareness of local food consumption as a sustainable practice among stakeholders could contribute to the further promotion of local food production and distribution.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought new challenges for food security and social and economic systems, but at the same time, it has provided opportunities for local food production. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has conducted a survey among different cities in order to monitor local food system status during the COVID-19 pandemic. About 40 percent of the cities that responded to the survey indicated that restrictive measures on human mobility introduced during the pandemic have led to a shortage of labor in local agriculture and food-related activities. The respondents further stated that the shortage of labor negatively affected local food production [8]. The FAO identified five main areas to support local food production and create resilient local food systems. One of these areas is promotion of local food production and providing SFSCs with a greater degree of self-sufficiency. The new barriers to, and opportunities for, local food production during the COVID-19 pandemic have been studied in the scientific literature. The COVID-19 pandemic has forced both customers and restaurants to shift their food habits to more locally grown products; therefore, purchasing local food products has become one of the most notable sustainable practices [9]. The COVID-19 pandemic will have long-lasting effects on food supply chains, including the growth of online grocery shopping and the extent to which consumers will prioritize ‘local’ food supply chains [10]. While in some countries the COVID-19 pandemic significantly restricted local food systems and created more food insecurity, in other countries local food systems continued to operate and were even strengthened by higher social capital and adaptive capacities [11].

2. Study Characteristics

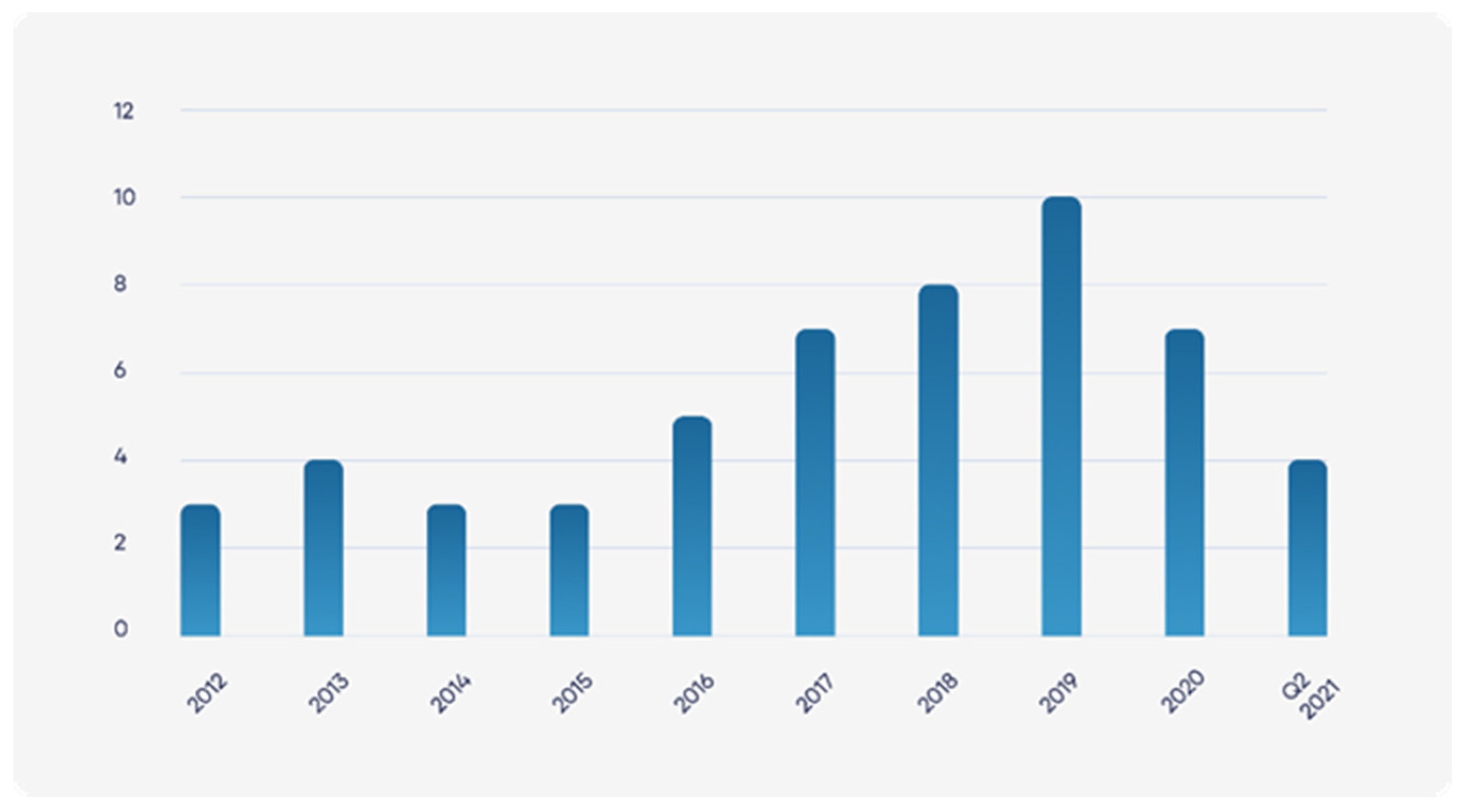

The literature retrieved shows a steady growing trend of the research in the field of consumers’ preference for local food starting from 2016 (Figure 1). Although researchers observe a slight decrease in the studies in the year 2020, the decrease can be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic. Given that almost all the studies were conducted using surveys the lockdowns made it impossible to conduct the research properly. The literature sample comprises 2 quarters of the year 2021 and as researchers can see the number of literature publications in 6 month of 2021, researchers may expect that the total number of the studies in 2021 will approach the pre-COVID period.

Figure 1. Literature publications per year.

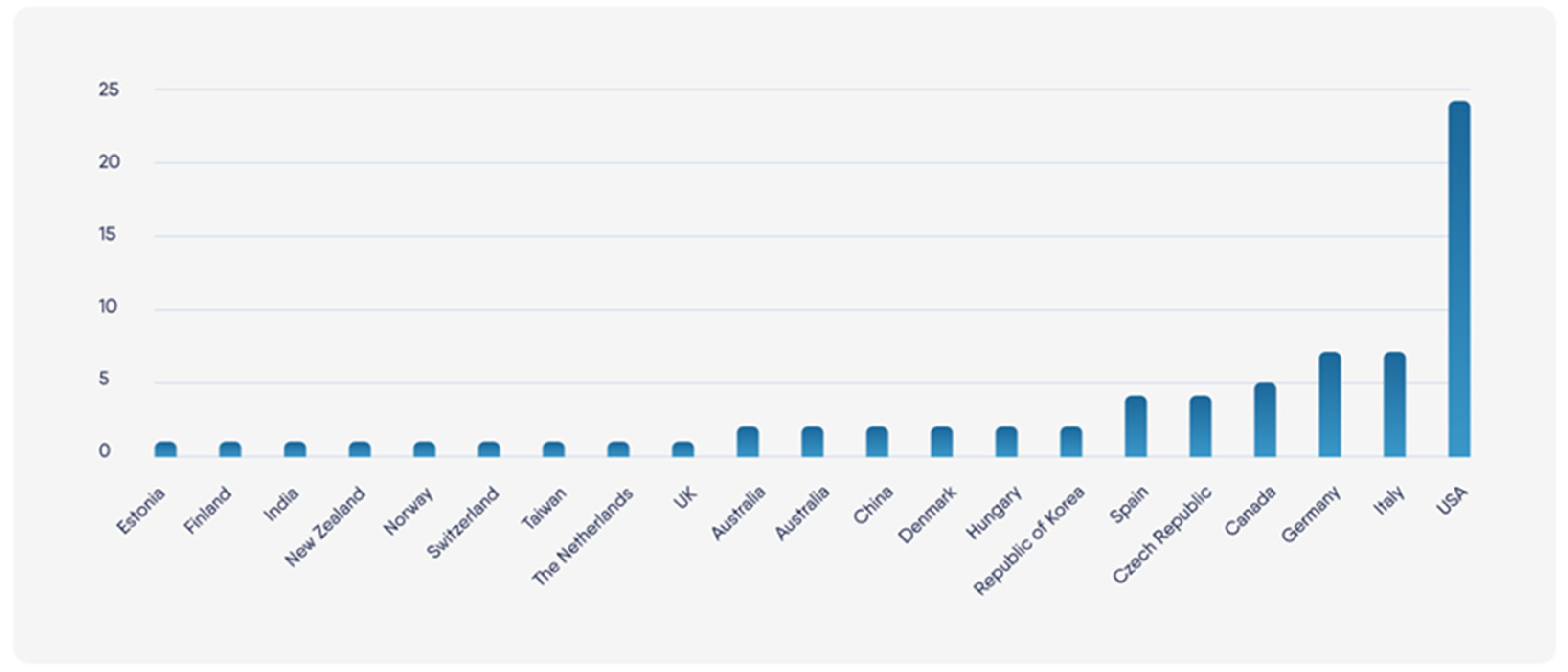

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the literature works by the countries which the researchers whose papers researchers examined. The leader of research on consumer preference for local food is the USA, with 24 papers on the topic. Italy and Germany have seven papers each, which make them European leaders in research in the field of consumer preference for local food. Researchers also observed the presence of research from Canada (5 papers), and Czech Republic and Spain (4 papers).

Figure 2. Distribution of the literature by country.

The researchers found it interesting to track the distribution of food types by country. In order to do so, researchers collected the food types discussed in the literature and matched them with the countries where the research was conducted. As can be observed from Table 1, there is no dependence of the food type on geography, except for Guadeloupe (yams) and India (mung bean), who considered these products as indigenous. The USA and Germany had the widest range of studied products. This evidence is apt, as the USA and Germany are the leaders in research on this topic.

Table 1. Food type distribution by country.

| Australia | Canada | Denmark | Estonia | Finland | Germany | Guadeloupe | Hungary | India | Italy | New Zealand | Spain | USA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apples | / | / | / | / | |||||||||

| beef | / | ||||||||||||

| beef salami | / | ||||||||||||

| beer | / | ||||||||||||

| blackberry jam | / | ||||||||||||

| bread | / | ||||||||||||

| broccoli | / | ||||||||||||

| butter | / | ||||||||||||

| chicken breasts | / | / | |||||||||||

| clams | / | ||||||||||||

| craft beer | / | ||||||||||||

| eggs | / | / | / | ||||||||||

| flour | / | ||||||||||||

| fresh lamb meat | / | ||||||||||||

| fruit yogurt | / | ||||||||||||

| garlic | / | ||||||||||||

| hard apple cider | / | ||||||||||||

| honey | / | / | |||||||||||

| ketchup | / | ||||||||||||

| lemons | / | ||||||||||||

| lettuce | / | ||||||||||||

| milk | / | / | / | / | |||||||||

| mung bean | / | ||||||||||||

| mussels | / | ||||||||||||

| oysters | / | ||||||||||||

| pork | / | ||||||||||||

| pork chops | / | ||||||||||||

| pork cutlet | / | ||||||||||||

| rice | / | ||||||||||||

| saffron | / | ||||||||||||

| scallops | / | ||||||||||||

| seaweed salad | / | ||||||||||||

| steak | / | ||||||||||||

| strawberries | / | ||||||||||||

| tomatoes | / | / | / | ||||||||||

| wine | / | ||||||||||||

| yams | / |

Table 2 represents the distribution of the keywords used in the studied papers by frequency, in a numerical expression and in percentage. A significant finding of this analysis was that the only keywords that included the word ‘sustainable’ or its derivatives were ‘sustainable food’, which was mentioned twice [12][13] in the studied literature, which amounts to ‘sustainable food’ only being included in 3.92% of all the keywords used; and with ‘sustainability’ being mentioned three times, 5.88% [14][15]. This outcome underlines that sustainable issues were not widely studied in the literature sample.

Table 2. Distribution of the keywords by frequency.

| Word Combination | Frequency | % | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| local food | 29 | 56.86 | 1 |

| willingness to pay | 14 | 27.45 | 2 |

| consumer preferences | 13 | 25.49 | 3 |

| organic | 13 | 25.49 | 3 |

| choice experiment | 11 | 21.57 | 5 |

| analysis | 7 | 13.73 | 6 |

| attributes | 6 | 11.76 | 7 |

| consumer behavior | 5 | 9.80 | 8 |

| consumer preference | 4 | 7.84 | 9 |

| local foods | 4 | 7.84 | 9 |

| oysters | 4 | 7.84 | 9 |

| regional food | 4 | 7.84 | 9 |

| latent class | 3 | 5.88 | 13 |

| marketing | 3 | 5.88 | 13 |

| perception | 3 | 5.88 | 13 |

| product | 3 | 5.88 | 13 |

| sustainability | 3 | 5.88 | 13 |

| branding program | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| choice experiments | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| choice-based conjoint analysis | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| cider | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| class segmentation | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| component analysis | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| conjoint analysis | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| consumer behavior | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| consumer demand | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| country of origin | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| credence attributes | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| discrete choice experiment | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| economics | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| experiments | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| farm | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| farmers | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| field experiment | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| food miles | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| food origin | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| food system | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| health | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| horticulture | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| latent class segmentation | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| logistic regression | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| market | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| organic production | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| price | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| principal component analysis | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| production | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| quality perception | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| seafood | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| supply chain | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| sustainable food | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

| tomatoes | 2 | 3.92 | 18 |

Figure 3 represents a word cloud of the keywords of the studied papers. As in Table 3, researchers see the common presence of the keyword combinations ‘local food’, ‘consumer preferences’, and ‘willingness to pay’, since these keywords were used to retrieve the sample. Other noticeable keywords are related to the research and analysis methods applied in the studies: ‘choice experiment’, ‘principal component analysis’, and ‘logistic regression’.

Figure 3. Keyword word cloud.

Table 3. Research method.

| Paper | Methodology |

|---|---|

| Holmes and Yan 2012 [16] | hypothetical choice experiment |

| Lesschaeve et al. 2012 [17] | online survey |

| Carroll et al. 2012 [18] | choice experiment |

| Grebitus et al. 2013 [19] | experimental auction, non-hypothetical Vickrey auction |

| Kalabova et al. 2013 [20] | online/offline questionnaire survey |

| Rikkonen et al. 2013 [21] | online questionnaires or/and phone interviews |

| Tempesta and Vecchiato 2013 [22] | choice experiment |

| Denver and Jensen 2014 [23] | choice experiment |

| Gracia 2014 [24] | real choice experiment |

| Moor et al. 2014 [25] | Survey |

| Barlagne et al. 2015 [26] | an economic experiment |

| Hasselbach and Roosen 2015 [27] | Interviews |

| Meas et al. 2015 [28] | choice experiment |

| Aprile et al. 2016 [29] | Survey |

| Hempel and Hamm 2016a [30] | survey, choice experiment |

| Hempel and Hamm 2016b [31] | offline survey, choice experiment |

| Lim and Hu 2016 [32] | choice experiment |

| Schifani et al. 2016 [33] | face-to-face questionnaire |

| Berg and Preston, 2017 [34] | online and offline survey |

| Ferrazzi et al. 2017 [35] | Survey |

| Kecinski et al. 2017 [36] | dichotomous choice field experiment |

| Mugera et al. 2017 [37] | random utility discrete choice model framework |

| Palmer et al. 2017 [38] | focus groups, survey |

| Sanova et al., 2017 [39] | Survey |

| Singh et al. 2017 [40] | semi-structured and structured interviews |

| Arsil et al. 2018 [41] | Survey |

| Brayden et al. 2018 [42] | online survey, choice experiment |

| Byrd et al. 2018 [43] | online survey, choice experiments |

| Hashem et al. 2018 [44] | semi-structured interviews, survey |

| Picha and Skorepa 2018 [14] | Survey |

| Picha et al. 2018 [45] | offline survey |

| Printezis and Grebitus 2018 [46] | hypothetical online choice experiment |

| Wenzig and Gruchmann 2018 [47] | Survey |

| Annunziata et al. 2019 [12] | self-administered questionnaire |

| Denver et al. 2019 [48] | quantitative survey, choice experiment |

| Fan et al. 2019 [49] | economic experiment |

| Farris et al. 2019 [50] | discrete choice experiment |

| Meyerding and Trajer 2019 [51] | survey, choice experiment |

| Meyerding et al. 2019 [52] | survey, choice experiment |

| Profeta and Hamm 2019 [53] | Interviews |

| Richard and Pivarnik 2019 [54] | Survey |

| Skallerud and Wien 2019 [55] | Survey |

| Werner et al. 2019 [56] | focus groups |

| Chen et al. 2020 [13] | online survey |

| Kiss et al. 2020 [57] | online survey |

| Li et al. 2020a [58] | framed field experiment |

| Li et al. 2020b [59] | incentive-compatible framed field experiment |

| Oravecz et al. 2020 [60] | personal interview by a paper-based questionnaire with open and decisive questions |

| Sanjuan-Lopez and Resano-Ezcaray 2020 [15] | hypothetical and real choice experiments |

| Yang and Leung 2020 [61] | hedonic price model |

| Attalah et al. 2021 [62] | choice experiment |

| He et al. 2021 [63] | Experiment |

| Jensen et al. 2021 [64] | online survey |

| Moreno and Malone 2021 [65] | a discrete choice experiment, the open-ended survey |

Table 3 shows the methodologies applied in the studied literature. Since, all the articles studied consumer preferences for local food, in most of the cases, quantitative methods of analysis were applied: offline and online consumer surveys with open-end and closed-end questions and choice experiments. Some research works applied qualitative methods, such as focus groups and interviews, in order to gather evidence.

References

- United Nations. Independent Group of Scientists Appointed by the Secretary-General, Global Sustainable Development Report 2019: The Future is Now—Science for Achieving Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA). SDG Good Practices. A Compilation of Success Stories and Lessons Learned in SDG Implementation, 1st ed.; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Galli, F.; Brunori, G. (Eds.) Short Food Supply Chains as Drivers of Sustainable Development. Evidence Document; Document developed in the framework of the FP7 project FOODLINKS (GA No. 265287); Laboratorio di Studi Rurali Sismondi: Pisa, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978-88-90896-01-9.

- Rucabado-Palomar, T.; Cuéllar-Padilla, M. Short food supply chains for local food: A difficult path. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 182–191.

- González-Azcárate, M.; Cruz Maceín, J.L.; Bardají, I. Why buying directly from producers is a valuable choice? Expanding the scope of short food supply chains in Spain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 911–920.

- Kumar, S.; Talwar, S.; Murphy, M.; Kaur, P.; Dhir, A. A behavioural reasoning perspective on the consumption of local food. A study on REKO, a social media-based local food distribution system. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104264.

- Enthoven, L.; Van den Broeck, G. Local food systems: Reviewing two decades of research. Agric. Syst. 2021, 193, 103226.

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). COVID-19 and the Role of Local Food Production in Building More Resilient Local Food Systems; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2020.

- Alsetoohy, O.; Ayoun, B.; Abou-Kamar, M. COVID-19 Pandemic Is a Wake-Up Call for Sustainable Local Food Supply Chains: Evidence from Green Restaurants in the USA. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9234.

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 171–176.

- Paganini, N.; Adinata, K.; Buthelezi, N.; Harris, D.; Lemke, S.; Luis, A.; Koppelin, J.; Karriem, A.; Ncube, F.; Nervi Aguirre, E.; et al. Growing and Eating Food during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Farmers’ Perspectives on Local Food System Resilience to Shocks in Southern Africa and Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8556.

- Annunziata, A.; Agovino, M.; Mariani, A. Sustainability of Italian families’ food practices: Mediterranean diet adherence combined with organic and local food consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 86–96.

- Chen, X.; Gao, Z.; McFadden, B. Reveal Preference Reversal in Consumer Preference for Sustainable Food Products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 79, 103754.

- Picha, K.; Skorepa, L. Preference to Food with a Regional Brand. Qual.-Access Success 2018, 19, 134–139.

- Sanjuan-Lopez, A.; Resano-Ezcaray, H. Labels for a Local Food Speciality Product: The Case of Saffron. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 778–797.

- Holmes, T.J.; Yan, R.; Skaggs, R. Predicting Consumers’ Preferences for and Likely Buying of Local and Organic Produce: Results of a Choice Experiment. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2012, 18, 369–384.

- Lesschaeve, I.; Campbell, B.L.; Bowen, A.J.; Onufrey, S.R.; Moskowitz, H.R. Assessing consumers’ mindsets for purchasing organic and local produce: Importance of perceived product and emotional benefits. Acta Hortic. 2012, 933, 653–660.

- Carroll, K.A.; Bernard, J.C.; Pesek, J.D., Jr. Consumer preferences for tomatoes: The influence of local, organic, and state program promotions by purchasing venue. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2013, 38, 379–396.

- Grebitus, C.; Lusk, J.; Nayga, R. Effect of distance of transportation on willingness to pay for food. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 88, 67–75.

- Kalabova, J.; Mokry, S.; Turčinkova, J. Regional differences of consumer preferences when shopping for regional products. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2013, 61, 2255–2259.

- Rikkonen, P.; Kotro, J.; Koistinen, L.; Penttila, K.; Kauriinoja, H. Opportunities for local food suppliers to use locality as a competitive advantage—A mixed survey methods approach. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2013, 63, 29–37.

- Tempesta, T.; Vecchiato, D. An analysis of the territorial factors affecting milk purchase in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 27, 35–43.

- Denver, S.; Jensen, J. Consumer preferences for organically and locally produced apple. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 129–134.

- Gracia, A. Consumers’ preferences for a local food product: A real choice experiment. Empir. Econ. 2014, 47, 111–128.

- Moor, U.; Moor, A.; Põldma, P.; Heinmaa, L. Consumer preferences of apples in Estonia and changes in attitudes over five years. Agric. Food Sci. 2014, 23, 135–145.

- Barlagne, C.; Bazoche, P.; Thomas, A.; Ozier-Lafontaine, H.; Causeret, F.; Blazy, J. Promoting local foods in small island states: The role of information policies. Food Policy 2015, 57, 62–72.

- Hasselbach, J.L.; Roosen, J. Motivations behind Preferences for Local or Organic Food. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2015, 27, 295–306.

- Meas, T.; Hu, W.; Batte, M.; Woods, T.; Ernst, S. Substitutes or Complements? Consumer Preference for Local and Organic Food Attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 97, 1044–1071.

- Aprile, M.C.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes toward Local Food Products. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 19–42.

- Hempel, C.; Hamm, U. Local and/or organic: A study on consumer preferences for organic food and food from different origins. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 732–741.

- Hempel, C.; Hamm, U. How important is local food to organic-minded consumers? Appetite 2016, 96, 309–318.

- Lim, K.H.; Hu, W. How Local Is Local? A Reflection on Canadian Local Food Labeling Policy from Consumer Preference. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 64, 71–88.

- Schifani, G.; Romeo, P.; Guccione, G.; Schimmenti, E.; Columba, P.; Migliore, G. Conventions of Quality in Consumer Preference toward Local Honey in Southern Italy. Qual.-Access Success 2016, 17, 92–97.

- Berg, N.; Preston, K. Willingness to pay for local food? Consumer preferences and shopping behavior at Otago Farmers Market. Transp. Res. Part A—Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 343–361.

- Ferrazzi, G.; Ventura, V.; Ratti, S.; Balzaretti, C. Consumers’ preferences for a local food product: The case of a new Carnaroli rice product in Lombardy. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2017, 6, 71–74.

- Kecinski, M.; Messer, K.D.; Knapp, L.; Shirazi, Y. Consumer Preferences for Oyster Attributes: Field Experiments on Brand, Locality, and Growing Method. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2017, 46, 315–337.

- Mugera, A.; Burton, M.; Downsborough, E. Consumer Preference and Willingness to Pay for a Local Label Attribute in Western Australian Fresh and Processed Food Products. J. Food Mark. 2017, 23, 452–472.

- Palmer, A.; Santo, R.; Berlin, L.; Bonanno, A.; Clancy, K.; Giesecke, C.; Hinrichs, C.C.; Lee, R.; McNab, P.; Rocker, S. Between global and local: Exploring regional food systems from the perspectives of four communities in the U.S. Northeast. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2017, 7, 187–205.

- Šanova, P.; Svobodova, J.; Laputkova, A. Using multiple correspondence analysis to evaluate selected aspects of behaviour of consumers purchasing local food products. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2017, 65, 2083–2093.

- Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Dahiya, P.; van Boekel, M.; Ruivenkamp, G. Local preferences of mung bean qualities for food autonomy in India. Dev. Pract. 2017, 27, 247–259.

- Arsil, P.; Li, E.; Bruwer, J.; Lyons, G. Motivation-based segmentation of local food in urban cities: A decision segmentation analysis approach. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2195–2207.

- Brayden, W.C.; Noblet, C.L.; Evans, K.S.; Rickard, L. Consumer preferences for seafood attributes of wild-harvested and farm-raised products. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2018, 22, 362–382.

- Byrd, E.S.; Widmar, N.J.O.; Wilcox, M.D. Are Consumers Willing to Pay for Local Chicken Breasts and Pork Chops? J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 235–248.

- Hashem, S.; Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Schimmenti, E.; Padel, S. Motives for buying local, organic food through English box schemes. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1600–1614.

- Pícha, K.; Navrátil, J.; Švec, R. Preference to local food vs. preference to “National” and regional food. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 125–145.

- Printezis, I.; Grebitus, C. Marketing Channels for Local Food. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 161–171.

- Wenzig, J.; Gruchmann, T. Consumer Preferences for Local Food: Testing an Extended Norm Taxonomy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1313.

- Denver, S.; Jensen, J.; Olsen, S.; Christensen, T. Consumer Preferences for “Localness” and Organic Food Production. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 668–689.

- Fan, X.; Gómez, M.I.; Coles, P.S. Willingness to Pay, Quality Perception, and Local Foods: The Case of Broccoli. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2019, 48, 414–432.

- Farris, J.; Malone, T.; Robison, L.J.; Rothwell, N.L. Is Localness about Distance or Relationships? Evidence from Hard Cider. J. Wine Econ. 2019, 14, 252–273.

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Trajer, N. Consumer preferences for local origin: Is closer better? The case of fresh tomatoes and ketchup in Germany. Acta Hortic. 2019, 1233, 193–200.

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Trajer, N.; Lehberger, M. What is local food? The case of consumer preferences for local food labeling of tomatoes in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 30–43.

- Profeta, A.; Hamm, U. Consumers’ expectations and willingness-to-pay for local animal products produced with local feed. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 651–659.

- Richard, N.; Pivarnik, L. Rhode Island branding program for local seafood: Consumer perceptions, awareness, and willingness-to-pay. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2019, 9, 13–29.

- Skallerud, K.; Wien, A. Preference for local food as a matter of helping behaviour: Insights from Norway. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 67, 79–88.

- Werner, S.; Lemos, S.R.; McLeod, A.; Halstead, J.M.; Gabe, T.; Huang, J.C.; Liang, C.L.; Shi, W.; Harris, L.; McConnon, J. Prospects for New England Agriculture: Farm to Fork. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2019, 48, 473–504.

- Kiss, K.; Ruszkai, C.; Szucs, A.; Koncz, G. Examining the role of local products in rural development in the light of consumer preferences-Results of a consumer survey from Hungary. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5473.

- Li, T.; Ahsanuzzaman; Messer, K. Is This Food ‘Local’? Evidence from a Framed Field Experiment. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 45, 179–198.

- Li, T.; Messer, K.; Mamadzhanov, A.; McCluskey, J. Preferences for local food: Tourists versus local residents. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Rev. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 429–444.

- Oravecz, T.; Mucha, L.; Magda, R.; Totth, G.; Illés, C.B. Consumers’ preferences for locally produced honey in Hungary. Acta Univ. Agric. Et Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2020, 68, 407–418.

- Yang, Y.; Leung, P. Price premium or price discount for locally produced food products? A temporal analysis for Hawaii. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2020, 25, 591–610.

- Atallah, S.S.; Bazzani, C.; Ha, K.A.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Does the origin of inputs and processing matter? Evidence from consumers’ valuation for craft beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 89, 104146.

- He, C.; Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Sims, C.; Nayga, R. Does local label bias consumer taste buds and preference? Evidence of a strawberry sensory experiment. Agribusiness 2021, 37, 550–568.

- Jensen, K.L.; DeLong, K.L.; Gill, M.B.; Hughes, D.W. Consumer willingness to pay for locally produced hard cider in the USA. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2021, 33, 411–431.

- Moreno, F.; Malone, T. The Role of Collective Food Identity in Local Food Demand. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2021, 50, 22–42.

More

Information

Subjects:

Operations Research & Management Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

04 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No