| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Karl Munger | + 2045 word(s) | 2045 | 2022-02-17 07:42:25 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | + 46 word(s) | 2091 | 2022-03-02 06:57:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

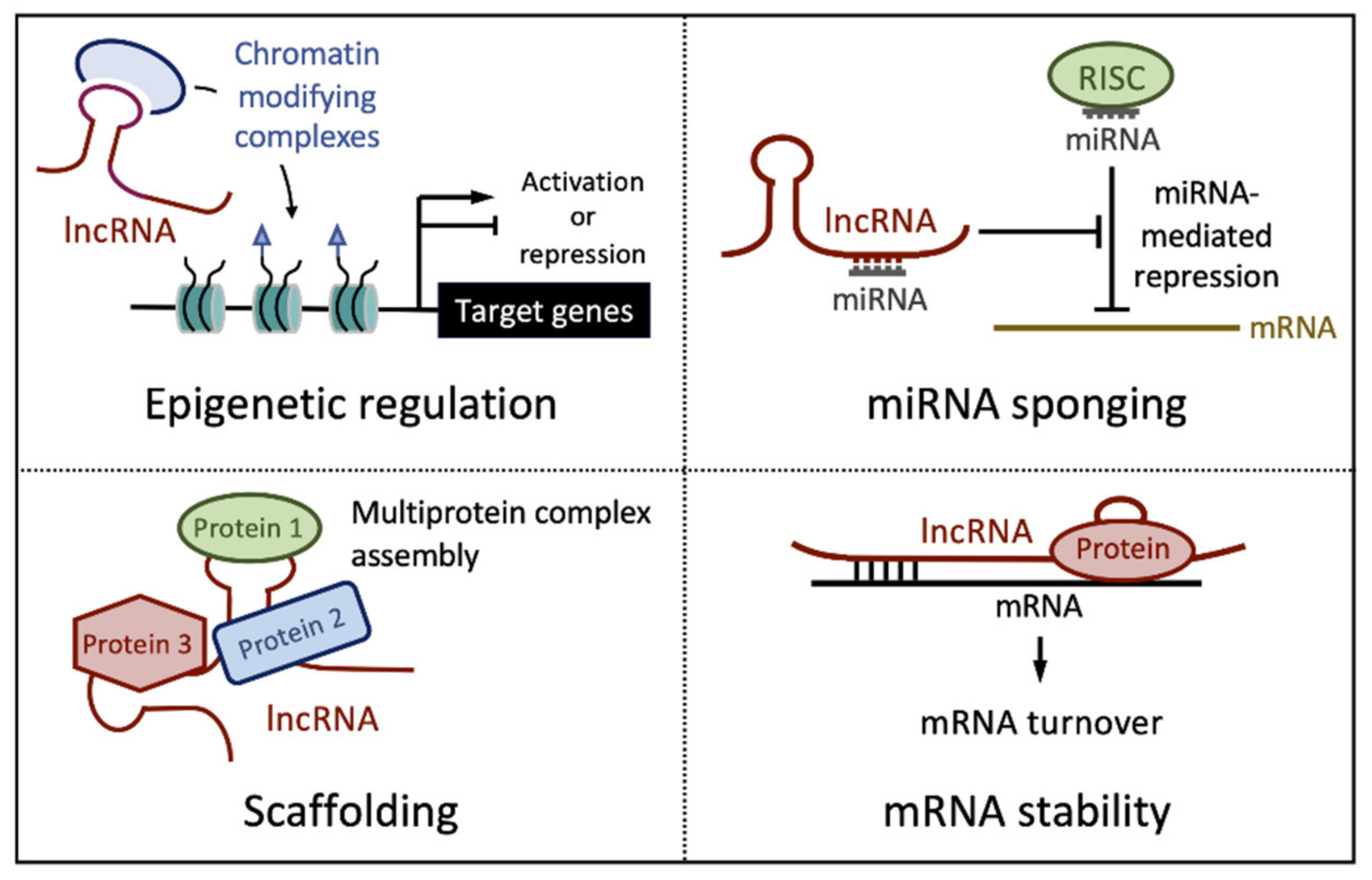

Papillomaviruses are a large family of non-enveloped viruses with ~8000 base pair, circular, double stranded DNA genomes. They have been detected in almost all vertebrates, are highly host-specific and preferentially infect squamous epithelial tissues. Infections with high-risk human papillomaviruses cause ~5% of all human cancers. E6 and E7 are the only viral genes that are consistently expressed in cancers, and they are necessary for tumor initiation, progression, and maintenance. E6 and E7 encode small proteins that lack intrinsic enzymatic activities and they function by binding to cellular regulatory molecules, thereby subverting normal cellular homeostasis. Much effort has focused on identifying protein targets of the E6 and E7 proteins, but it has been estimated that ~98% of the human transcriptome does not encode proteins. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as transcripts of >200 nucleotides with no or limited coding potential of <100 amino acids. There is a growing interest in studying noncoding RNAs as biochemical targets and biological mediators of human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 oncogenic activities.

1. Human Papillomaviruses as Oncogenic Drivers

2. Long Noncoding RNAs

3. Deregulation of lncRNAs in Cervical Carcinomas

|

lncRNA |

Oncogenic Phenotype |

Proposed Mechanism |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

ANRIL |

Proliferation, migration, invasion |

PI3K/AKT; Cyclin D1, CDK4, CDK6, N-cadherin, Vimentin expression |

|

|

ARAP1-AS1 |

Proliferation, invasion |

MYC translation by PSF/PTB |

[28] |

|

BLACAT1 |

Proliferation, migration, invasion |

WNT signaling/β-catenin |

[29] |

|

CCAT2 |

Proliferation, apoptosis |

None reported |

[30] |

|

CCEPR (CCHE1) |

Proliferation |

PCNA mRNA stabilization |

[31] |

|

Proliferation |

independent of PCNA mRNA |

[32] |

|

|

CRNDE |

Proliferation, migration, invasion |

miR-183 sponging/cyclin B1 |

[33] |

|

Proliferation |

PUMA expression |

[34] |

|

|

DANCR |

Proliferation, migration, invasion |

miR-665 sponging/TGFβ-R1-ERK-SMAD |

[35] |

|

Proliferation, migration, invasion, epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) |

miR-335-5p sponging/ROCK1 |

[36] |

|

|

EBIC (TMPOP2) |

Motility, invasion |

E-cadherin silencing by EZH2 |

[37] |

|

Proliferation |

miR-375, miR-139 sponging HPV E6/E7 expression |

[38] |

|

|

FAM83H-AS1 |

Proliferation, migration and apoptosis |

G1/S-phase transition |

[39] |

|

GATA6-AS |

Migration, invasion |

MTK-1 |

[40] |

|

H19 |

Proliferation, anchorage independent growth |

None reported |

[41] |

|

HOTAIR |

Apoptosis, invasion, migration |

NOTCH signaling |

[42] |

|

Apoptosis, proliferation, invasion |

miR-23b sponging/MAPK1 axis |

[43] |

|

|

Autophagy, EMT |

WNT signaling |

[44] |

|

|

Proliferation |

miR-143-3p sponging/BCL2 |

[45] |

|

|

HOXD-AS1 |

Proliferation |

Ras/ERK |

[46] |

|

Linc00483 |

Proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, migration |

miR-508-3p sponging/RGS17 |

[47] |

|

LINP1 |

DNA damage repair (Non-homologous end joining) |

KU80, DNA-PKcs binding |

[48] |

|

Lnc-IL7R |

Apoptosis |

BCL2/caspase 3 |

[49] |

|

LUCAT1 |

Proliferation, migration, invasion |

miR-181a sponging |

[50] |

|

MALAT1 |

Cell invasion and metastasis |

inhibition of EMT genes |

[51] |

|

Proliferation, migration, invasion |

miR-625-5p/AKT2 |

[52] |

|

|

Proliferation |

Mir-625-5p/NF-kB signaling |

[53] |

|

|

Cisplatin resistance |

PI3K/AKT |

[54] |

|

|

MIR205HG |

Proliferation, apoptosis, migration |

SRSF1/KRT17 axis |

[55] |

|

NEAT1 |

Proliferation, invasion |

PI3K/AKT |

|

|

Colony formation, migration, invasion |

miR-133a sponging/SOX4 |

[58] |

|

|

NORAD |

Proliferation, invasion |

miR-590-3p sponging/SIP1 |

[59] |

|

PANDAR |

Proliferation |

None reported |

[60] |

|

PVT1 |

Proliferation, invasion |

Inhibiting TGFβ; miR-140-5p sponging/SMAD3 |

|

|

EMT, chemoresistance |

miR-195 epigenetic silencing |

[63] |

|

|

SNHG8 |

Proliferation, apoptosis |

RECK silencing by EZH2 |

[64] |

|

SNHG12 |

Proliferation, apoptosis |

ERK/Slug |

[65] |

|

SNHG16 |

Proliferation, invasion |

PARP9 expression by SPI1 binding |

[66] |

|

TUG1 |

Proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, tumor growth |

miR-138-5p sponging/SIRT1 |

[67] |

|

Proliferation, apoptosis, EMT |

BCL-2, caspase 3; fibronectin, vimentin, and cytokeratin |

[68] |

|

|

TP73-AS1 |

Proliferation, migration |

miR-329-3p sponging/SMAD2 |

[69] |

|

Proliferation, migration, invasion |

miR-607 sponging/CCND2 |

[70] |

|

|

UCA1 |

Radioresistance |

HK2/glycolytic pathway |

[71] |

|

XIST |

Proliferation |

miR-140-5p sponging/ORC1 |

[72] |

|

Proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, EMT |

miR-200a sponging/FUS |

[73] |

|

|

ZEB-AS1 |

Proliferation, migration, invasion, EMT |

ZEB1 expression |

[74] |

|

lncRNA |

Oncogenic Phenotype |

Proposed Mechanism |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

GAS5 |

Proliferation, invasion, migration |

E-cadherin, Vimentin |

[75] |

|

Proliferation, migration, invasion, colony formation |

miR-21 expression/STAT3 |

[76] |

|

|

Radiosensitivity |

miR-106b sponging/IER3 |

[77] |

|

|

HOTAIR |

Decreased polycomb repression |

Binding to HPV E7 |

[78] |

|

Lnc-CCDST |

Migration, invasion, angiogenesis |

DHX9, MDM2 scaffolding |

[79] |

|

MEG3 |

Proliferation, apoptosis |

Binding, degradation of P-STAT3 |

[80] |

|

Proliferation, colony formation, apoptosis |

miR-21-5p expression/TP53 |

[81] |

|

|

STXBP5-AS1 |

Viability, invasion |

miR-96-5p expression/PTEN |

[82] |

|

TINCR |

Differentiation, colony formation, migration |

S100A8 and other ZNF750 targets |

[83] |

|

WT1-AS |

Proliferation |

TP53 |

[84] |

|

Proliferation, invasion, migration |

miR-203a-5p binding/FOXN2 |

[85] |

|

|

XLOC_010588 |

Proliferation |

MYC mRNA binding/degradation |

[86] |

4. Deregulation of lncRNAs by HPV E6 and/or E7 Proteins

References

- Van Doorslaer, K.; Li, Z.; Xirasagar, S.; Maes, P.; Kaminsky, D.; Liou, D.; Sun, Q.; Kaur, R.; Huyen, Y.; McBride, A.A. The Papillomavirus Episteme: A major update to the papillomavirus sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D499–D506.

- Meyers, J.M.; Munger, K. The viral etiology of skin cancer. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, E29–E32.

- Howley, P.M.; Pfister, H.J. Beta genus papillomaviruses and skin cancer. Virology 2015, 479–480, 290–296.

- Schiffman, M.; Castle, P.E.; Jeronimo, J.; Rodriguez, A.C.; Wacholder, S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 2007, 370, 890–907.

- Moody, C.A.; Laimins, L.A. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: Pathways to transformation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 550–560.

- Wu, S.C.; Canarte, V.; Beeravolu, H.; Grace, M.; Sharma, S.; Munger, K. Chapter 4—Finding How Human Papillomaviruses Alter the Biochemistry and Identity of Infected Epithelial Cells. In Human Papillomavirus; Jenkins, D., Bosch, F.X., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 53–65.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Mesri, E.A.; Feitelson, M.A.; Munger, K. Human viral oncogenesis: A cancer hallmarks analysis. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 266–282.

- Roman, A.; Munger, K. The papillomavirus E7 proteins. Virology 2013, 445, 138–168.

- Vande Pol, S.B.; Klingelhutz, A.J. Papillomavirus E6 oncoproteins. Virology 2013, 445, 115–137.

- Ransohoff, J.D.; Wei, Y.; Khavari, P.A. The functions and unique features of long intergenic non-coding RNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 143–157.

- Brannan, C.I.; Dees, E.C.; Ingram, R.S.; Tilghman, S.M. The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990, 10, 28–36.

- Brown, C.J.; Ballabio, A.; Rupert, J.L.; Lafreniere, R.G.; Grompe, M.; Tonlorenzi, R.; Willard, H.F. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 1991, 349, 38–44.

- Derrien, T.; Johnson, R.; Bussotti, G.; Tanzer, A.; Djebali, S.; Tilgner, H.; Guernec, G.; Martin, D.; Merkel, A.; Knowles, D.G.; et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: Analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 1775–1789.

- Iyer, M.K.; Niknafs, Y.S.; Malik, R.; Singhal, U.; Sahu, A.; Hosono, Y.; Barrette, T.R.; Prensner, J.R.; Evans, J.R.; Zhao, S.; et al. The landscape of long noncoding RNAs in the human transcriptome. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 199–208.

- Necsulea, A.; Soumillon, M.; Warnefors, M.; Liechti, A.; Daish, T.; Zeller, U.; Baker, J.C.; Grützner, F.; Kaessmann, H. The evolution of lncRNA repertoires and expression patterns in tetrapods. Nature 2014, 505, 635–640.

- Ulitsky, I.; Shkumatava, A.; Jan, C.H.; Sive, H.; Bartel, D.P. Conserved function of lincRNAs in vertebrate embryonic development despite rapid sequence evolution. Cell 2011, 147, 1537–1550.

- Schoeftner, S.; Sengupta, A.K.; Kubicek, S.; Mechtler, K.; Spahn, L.; Koseki, H.; Jenuwein, T.; Wutz, A. Recruitment of PRC1 function at the initiation of X inactivation independent of PRC2 and silencing. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3110–3122.

- Rinn, J.L.; Kertesz, M.; Wang, J.K.; Squazzo, S.L.; Xu, X.; Brugmann, S.A.; Goodnough, L.H.; Helms, J.A.; Farnham, P.J.; Segal, E.; et al. Functional demarcation of active and silent chromatin domains in human HOX loci by noncoding RNAs. Cell 2007, 129, 1311–1323.

- Gomez, J.A.; Wapinski, O.L.; Yang, Y.W.; Bureau, J.-F.; Gopinath, S.; Monack, D.M.; Chang, H.Y.; Brahic, M.; Kirkegaard, K. The NeST long ncRNA controls microbial susceptibility and epigenetic activation of the interferon-γ locus. Cell 2013, 152, 743–754.

- Wang, K.C.; Yang, Y.W.; Liu, B.; Sanyal, A.; Corces-Zimmerman, R.; Chen, Y.; Lajoie, B.R.; Protacio, A.; Flynn, R.A.; Gupta, R.A.; et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature 2011, 472, 120–124.

- Morchikh, M.; Cribier, A.; Raffel, R.; Amraoui, S.; Cau, J.; Severac, D.; Dubois, E.; Schwartz, O.; Bennasser, Y.; Benkirane, M. HEXIM1 and NEAT1 Long Non-coding RNA Form a Multi-subunit Complex that Regulates DNA-Mediated Innate Immune Response. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 387–399.

- Paraskevopoulou, M.D.; Hatzigeorgiou, A.G. Analyzing MiRNA-LncRNA Interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1402, 271–286.

- Kretz, M.; Siprashvili, Z.; Chu, C.; Webster, D.E.; Zehnder, A.; Qu, K.; Lee, C.S.; Flockhart, R.J.; Groff, A.F.; Chow, J.; et al. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature 2013, 493, 231–235.

- Schmitt, A.M.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 452–463.

- Zhang, D.; Sun, G.; Zhang, H.; Tian, J.; Li, Y. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL indicates a poor prognosis of cervical cancer and promotes carcinogenesis via PI3K/Akt pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 85, 511–516.

- Zhang, W.-Y.; Liu, Y.-J.; He, Y.; Chen, P. Down-regulation of long non-coding RNA ANRIL inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer cells. Cancer Biomark. 2018, 23, 243–253.

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, D. Long non-coding RNA ARAP1-AS1 promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis through facilitating proto-oncogene c-Myc translation via dissociating PSF/PTB dimer in cervical cancer. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 1855–1866.

- Wang, C.H.; Li, Y.H.; Tian, H.L.; Bao, X.X.; Wang, Z.M. Long non-coding RNA BLACAT1 promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion in cervical cancer through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 3002–3009.

- Wu, L.; Jin, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, L. Roles of Long Non-Coding RNA CCAT2 in Cervical Cancer Cell Growth and Apoptosis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 875–879.

- Yang, M.; Zhai, X.; Xia, B.; Wang, Y.; Lou, G. Long noncoding RNA CCHE1 promotes cervical cancer cell proliferation via upregulating PCNA. Tumour Biol. 2015, 36, 7615–7622.

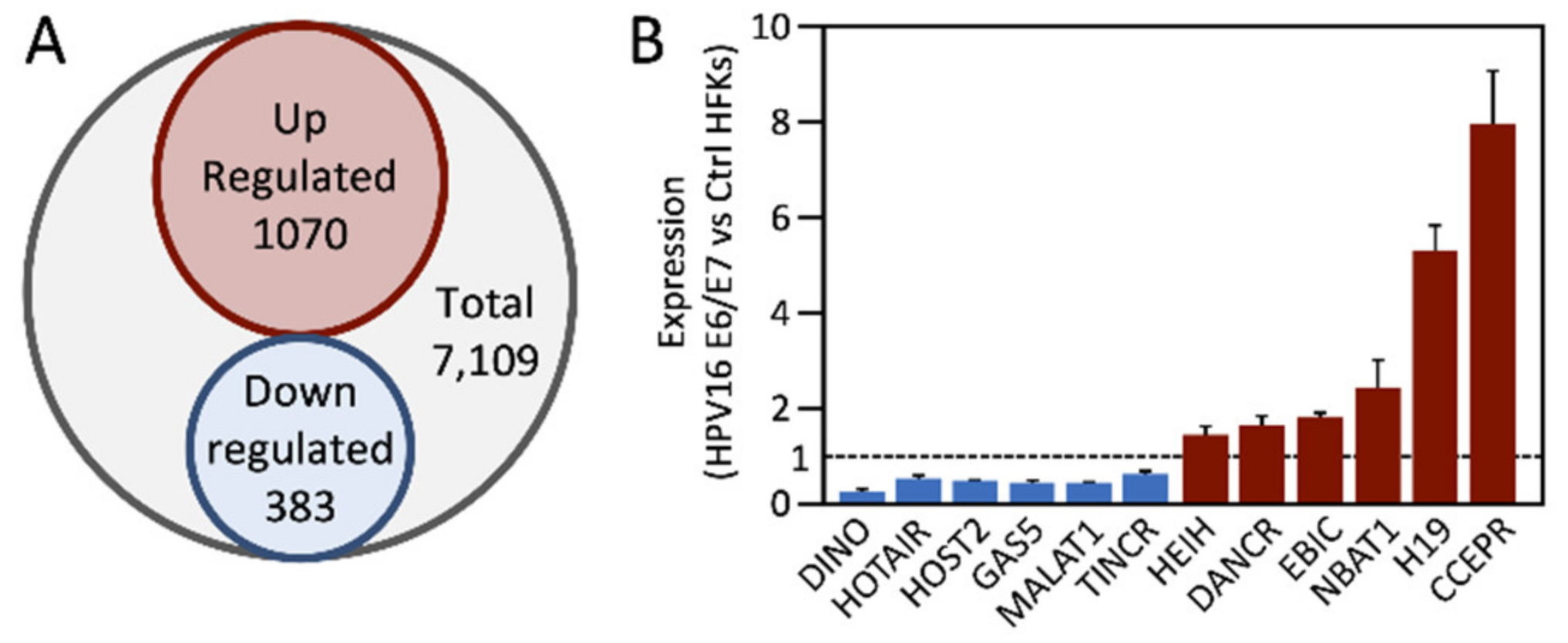

- Sharma, S.; Munger, K. Expression of the cervical carcinoma expressed PCNA regulatory (CCEPR) long noncoding RNA is driven by the human papillomavirus E6 protein and modulates cell proliferation independent of PCNA. Virology 2018, 518, 8–13.

- Bai, X.; Wang, W.; Zhao, P.; Wen, J.; Guo, X.; Shen, T.; Shen, J.; Yang, X. LncRNA CRNDE acts as an oncogene in cervical cancer through sponging miR-183 to regulate CCNB1 expression. Carcinogenesis 2020, 41, 111–121.

- Zhang, J.-J.; Fan, L.-P. Long non-coding RNA CRNDE enhances cervical cancer progression by suppressing PUMA expression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 108726.

- Cao, L.; Jin, H.; Zheng, Y.; Mao, Y.; Fu, Z.; Li, X.; Dong, L. DANCR-mediated microRNA-665 regulates proliferation and metastasis of cervical cancer through the ERK/SMAD pathway. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 913–925.

- Liang, H.; Zhang, C.; Guan, H.; Liu, J.; Cui, Y. LncRNA DANCR promotes cervical cancer progression by upregulating ROCK1 via sponging miR-335-5p. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 7266–7278.

- Sun, N.-X.; Ye, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, C.; Wang, S.-B.; Jin, Z.-J.; Sun, S.-H.; Wang, F.; Li, W. Long noncoding RNA-EBIC promotes tumor cell invasion by binding to EZH2 and repressing E-cadherin in cervical cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100340.

- He, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Lai, Y.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Shi, D.; Wang, N.; Luo, X.-G.; et al. Human Papillomavirus E6/E7 and Long Noncoding RNA TMPOP2 Mutually Upregulated Gene Expression in Cervical Cancer Cells. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01808-18.

- Barr, J.A.; Hayes, K.E.; Brownmiller, T.; Harold, A.D.; Jagannathan, R.; Lockman, P.R.; Khan, S.; Martinez, I. Long non-coding RNA FAM83H-AS1 is regulated by human papillomavirus 16 E6 independently of p53 in cervical cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 3662.

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Song, L.; Yao, D.; Tang, Q.; Zhou, J. Upregulation of lncRNA GATA6-AS suppresses the migration and invasion of cervical squamous cell carcinoma by downregulating MTK-1. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 2605–2611.

- Iempridee, T. Long non-coding RNA H19 enhances cell proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of cervical cancer cell lines. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 184–193.

- Lee, M.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Park, S.-A.; Chun, K.-H.; Cho, N.H.; Song, Y.S.; Kim, Y.T. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR increases tumour growth and invasion in cervical cancer by targeting the Notch pathway. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 44558–44571.

- Li, Q.; Feng, Y.; Chao, X.; Shi, S.; Liang, M.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Z. HOTAIR contributes to cell proliferation and metastasis of cervical cancer via targetting miR-23b/MAPK1 axis. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20171563.

- Guo, X.; Xiao, H.; Guo, S.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Lou, G. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR knockdown inhibits autophagy and epithelial-mesenchymal transition through the Wnt signaling pathway in radioresistant human cervical cancer HeLa cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 3478–3489.

- Liu, M.; Jia, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Fan, R. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR promotes cervical cancer progression through regulating BCL2 via targeting miR-143-3p. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2018, 19, 391–399.

- Hu, Y.C.; Wang, A.M.; Lu, J.K.; Cen, R.; Liu, L.L. Long noncoding RNA HOXD-AS1 regulates proliferation of cervical cancer cells by activating Ras/ERK signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 5049–5055.

- Hu, P.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, X.; Song, G.; Zhan, L.; Cao, Y. Long non-coding RNA Linc00483 accelerated tumorigenesis of cervical cancer by regulating miR-508-3p/RGS17 axis. Life Sci. 2019, 234, 116789.

- Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Shi, L.; Yu, X.; Gu, Y.; Sun, X. LINP1 facilitates DNA damage repair through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway and subsequently decreases the sensitivity of cervical cancer cells to ionizing radiation. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 439–447.

- Fan, Y.; Nan, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhong, H.; Zhou, W. Up-regulation of inflammation-related LncRNA-IL7R predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with cervical cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20180483.

- Zhang, L.; Liu, S.-K.; Song, L.; Yao, H.-R. SP1-induced up-regulation of lncRNA LUCAT1 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion of cervical cancer by sponging miR-181a. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 556–564.

- Sun, R.; Qin, C.; Jiang, B.; Fang, S.; Pan, X.; Peng, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Li, G. Down-regulation of MALAT1 inhibits cervical cancer cell invasion and metastasis by inhibition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol. Biosyst. 2016, 12, 952–962.

- Zhao, F.; Fang, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, S. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 promotes cell proliferation, migration and invasion in cervical cancer by targeting miR-625-5p and AKT2. Panminerva Med. 2020.

- Li, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ding, N.; Zhang, H.; Lu, M.; Cui, X.; Yu, X. MicroRNA-625-5p Sponges lncRNA MALAT1 to Inhibit Cervical Carcinoma Cell Growth by Suppressing NF-kappaB Signaling. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2020.

- Wang, N.; Hou, M.S.; Zhan, Y.; Shen, X.B.; Xue, H.Y. MALAT1 promotes cisplatin resistance in cervical cancer by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 7653–7659.

- Dong, M.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Song, L. Long non-coding RNA MIR205HG regulates KRT17 and tumor processes in cervical cancer via interaction with SRSF1. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2019, 111, 104322.

- Guo, H.M.; Yang, S.H.; Zhao, S.Z.; Li, L.; Yan, M.T.; Fan, M.C. LncRNA NEAT1 regulates cervical carcinoma proliferation and invasion by targeting AKT/PI3K. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 4090–4097.

- Wang, H.-L.; Hou, S.-Y.; Li, H.-B.; Qiu, J.-P.; Bo, L.; Mao, C.-P. Biological Function and Mechanism of Long Noncoding RNAs Nuclear-Enriched Abundant Transcript 1 in Development of Cervical Cancer. Chin. Med. J. 2018, 131, 2063–2070.

- Yuan, L.-Y.; Zhou, M.; Lv, H.; Qin, X.; Zhou, J.; Mao, X.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, H. Involvement of NEAT1/miR-133a axis in promoting cervical cancer progression via targeting SOX4. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 18985–18993.

- Huo, H.; Tian, J.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Qu, C.; Wang, N. Long non-coding RNA NORAD upregulate SIP1 expression to promote cell proliferation and invasion in cervical cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 106, 1454–1460.

- Huang, H.W.; Xie, H.; Ma, X.; Zhao, F.; Gao, Y. Upregulation of LncRNA PANDAR predicts poor prognosis and promotes cell proliferation in cervical cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 4529–4535.

- Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, L.; Cong, J.; Hou, J.; Liu, C. LncRNA PVT1 promotes the growth of HPV positive and negative cervical squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting TGF-β1. Cancer Cell Int. 2018, 18, 70.

- Chang, Q.-Q.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, Z.; Chang, S. LncRNA PVT1 promotes proliferation and invasion through enhancing Smad3 expression by sponging miR-140-5p in cervical cancer. Radiol. Oncol. 2019, 53, 443–452.

- Shen, C.-J.; Cheng, Y.-M.; Wang, C.-L. LncRNA PVT1 epigenetically silences miR-195 and modulates EMT and chemoresistance in cervical cancer cells. J. Drug Target. 2017, 25, 637–644.

- Qu, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Yuan, N.; Ma, M.; Chen, Y. LncRNA SNHG8 accelerates proliferation and inhibits apoptosis in HPV-induced cervical cancer through recruiting EZH2 to epigenetically silence RECK expression. J. Cell. Biochem. 2020.

- Lai, S.-Y.; Guan, H.-M.; Liu, J.; Huang, L.-J.; Hu, X.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wu, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, J.-Y. Long noncoding RNA SNHG12 modulated by human papillomavirus 16 E6/E7 promotes cervical cancer progression via ERK/Slug pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020.

- Tao, L.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q. Long noncoding RNA SNHG16 promotes the tumorigenicity of cervical cancer cells by recruiting transcriptional factor SPI1 to upregulate PARP9. Cell Biol. Int. 2020, 44, 773–784.

- Zhu, J.; Shi, H.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Li, F. Long non-coding RNA TUG1 promotes cervical cancer progression by regulating the miR-138-5p-SIRT1 axis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 65253–65264.

- Hu, Y.; Sun, X.; Mao, C.; Guo, G.; Ye, S.; Xu, J.; Zou, R.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Duan, P.; et al. Upregulation of long noncoding RNA TUG1 promotes cervical cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 471–482.

- Guan, M.M.; Rao, Q.X.; Huang, M.L.; Wang, L.J.; Lin, S.D.; Chen, Q.; Liu, C.H. Long Noncoding RNA TP73-AS1 Targets MicroRNA-329-3p to Regulate Expression of the SMAD2 Gene in Human Cervical Cancer Tissue and Cell Lines. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 8131–8141.

- Zhang, H.; Xue, B.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Fan, T. Long non-coding RNA TP73 antisense RNA 1 facilitates the proliferation and migration of cervical cancer cells via regulating microRNA-607/cyclin D2. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 3371–3378.

- Fan, L.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Gao, T.; Lin, Z.; Yao, T. Long non-coding RNA urothelial cancer associated 1 regulates radioresistance via the hexokinase 2/glycolytic pathway in cervical cancer. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 2247–2259.

- Chen, X.; Xiong, D.; Ye, L.; Wang, K.; Huang, L.; Mei, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Lai, X.; Zheng, L.; et al. Up-regulated lncRNA XIST contributes to progression of cervical cancer via regulating miR-140-5p and ORC1. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 45.

- Zhu, H.; Zheng, T.; Yu, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, L. LncRNA XIST accelerates cervical cancer progression via upregulating Fus through competitively binding with miR-200a. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 105, 789–797.

- Cheng, R.; Li, N.; Yang, S.; Liu, L.; Han, S. Long non-coding RNA ZEB1-AS1 promotes cell invasion and epithelial to mesenchymal transition through inducing ZEB1 expression in cervical cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 7245–7253.

- Yang, W.; Xu, X.; Hong, L.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Jiang, L. Upregulation of lncRNA GAS5 inhibits the growth and metastasis of cervical cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 23571–23580.

- Yao, T.; Lu, R.; Zhang, J.; Fang, X.; Fan, L.; Huang, C.; Lin, R.; Lin, Z. Growth arrest-specific 5 attenuates cisplatin-induced apoptosis in cervical cancer by regulating STAT3 signaling via miR-21. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 9605–9615.

- Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Li, G.; Cai, M.; Tan, C.; Han, X.; Han, L. LncRNA GAS5 confers the radio sensitivity of cervical cancer cells via regulating miR-106b/IER3 axis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 994–1001.

- Sharma, S.; Mandal, P.; Sadhukhan, T.; Roy Chowdhury, R.; Ranjan Mondal, N.; Chakravarty, B.; Chatterjee, T.; Roy, S.; Sengupta, S. Bridging Links between Long Noncoding RNA HOTAIR and HPV Oncoprotein E7 in Cervical Cancer Pathogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11724.

- Ding, X.; Jia, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, J.; Gao, S.-J.; Lu, C. A DHX9-lncRNA-MDM2 interaction regulates cell invasion and angiogenesis of cervical cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 1750–1765.

- Zhang, J.; Gao, Y. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 inhibits cervical cancer cell growth by promoting degradation of P-STAT3 protein via ubiquitination. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 175.

- Zhang, J.; Yao, T.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Z. Long noncoding RNA MEG3 is downregulated in cervical cancer and affects cell proliferation and apoptosis by regulating miR-21. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016, 17, 104–113.

- Shao, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. LncRNA STXBP5-AS1 suppressed cervical cancer progression via targeting miR-96-5p/PTEN axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 117, 109082.

- Hazawa, M.; Lin, D.C.; Handral, H.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Mayakonda, A.; Ding, L.W.; Meng, X.; Sharma, A.; et al. ZNF750 is a lineage-specific tumour suppressor in squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene 2017, 36, 2243–2254.

- Zhang, Y.; Na, R.; Wang, X. LncRNA WT1-AS up-regulates p53 to inhibit the proliferation of cervical squamous carcinoma cells. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1052.

- Dai, S.G.; Guo, L.L.; Xia, X.; Pan, Y. Long non-coding RNA WT1-AS inhibits cell aggressiveness via miR-203a-5p/FOXN2 axis and is associated with prognosis in cervical cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 486–495.

- Liao, L.-M.; Sun, X.-Y.; Liu, A.-W.; Wu, J.-B.; Cheng, X.-L.; Lin, J.-X.; Zheng, M.; Huang, L. Low expression of long noncoding XLOC_010588 indicates a poor prognosis and promotes proliferation through upregulation of c-Myc in cervical cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 616–623.

- Aalijahan, H.; Ghorbian, S. Long non-coding RNAs and cervical cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2019, 106, 7–16.

- Dong, J.; Su, M.; Chang, W.; Zhang, K.; Wu, S.; Xu, T. Long non-coding RNAs on the stage of cervical cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 1923–1931.

- Shi, D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X. Long noncoding RNAs in cervical cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018, 14, 745–753.

- Iancu, I.V.; Anton, G.; Botezatu, A.; Huica, I.; Nastase, A.; Socolov, D.G.; Stanescu, A.D.; Dima, S.O.; Bacalbasa, N.; Plesa, A. LINC01101 and LINC00277 expression levels as novel factors in HPV-induced cervical neoplasia. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 3787–3794.

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Fang, S.; Jiang, B.; Qin, C.; Xie, P.; Zhou, G.; Li, G. The role of MALAT1 correlates with HPV in cervical cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2014, 7, 2135–2141.

- Harden, M.E.; Prasad, N.; Griffiths, A.; Munger, K. Modulation of microRNA-mRNA Target Pairs by Human Papillomavirus 16 Oncoproteins. MBio 2017, 8, e02170-16.