| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Angela Lupattelli | + 3106 word(s) | 3106 | 2022-02-14 04:10:38 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | + 30 word(s) | 3136 | 2022-02-28 03:06:24 | | | | |

| 3 | Bruce Ren | Meta information modification | 3136 | 2022-02-28 07:52:32 | | | | |

| 4 | Bruce Ren | -1 word(s) | 3135 | 2022-02-28 07:58:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

Peripartum or perinatal depression, which is depression arising in the period between the start of a pregnancy and the end of the first postpartum year. Multiple CPGs recommend antidepressant initiation or continuation based on maternal disease severity, non-response to first-line non-pharmacological interventions, and after risk-benefit assessment. Advice on treatment of comorbid anxiety is largely missing or unspecific. Antidepressant dispensing data suggest general prescribers’ compliance with the preferred substances of the CPG, although country-specific differences were noted. To conclude, there is an urgent need for harmonized, up-to-date CPGs for pharmacological management of peripartum depression and comorbid anxiety in Europe. The recommendations need to be informed by the latest available evidence so that healthcare providers and women can make informed, evidence-based decisions about treatment choices.

1. Introduction

2. Treatment of Peripartum Depression with Antidepressants

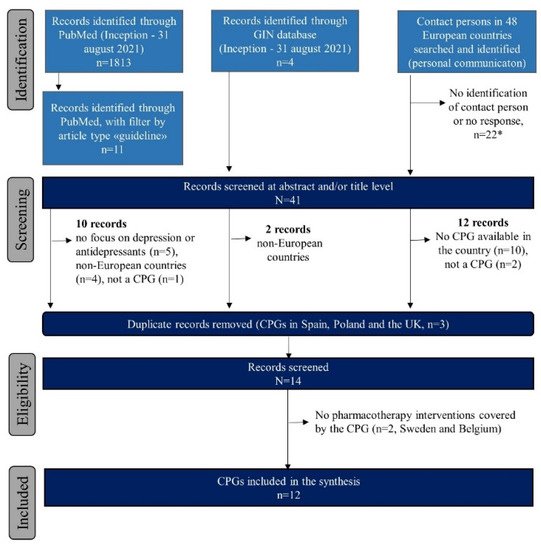

2.1. Identified Clinical Practice Guidelines

3.2. Pharmacological Interventions for Treatment of Antenatal Depression

| Country, Publication Year, Type | New Depression, Initiate AD | Preexisting Depression, Continue AD | AD Dose Adjustment and Monitoring | Switching AD | Preferred or Not Preferred AD |

AD Use before vs during Pregnancy (%) | Most Common ADs Used during Pregnancy | Treatment of Co-Morbid Anxiety | Other Psychotropics during Pregnancy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark [17] PMH-S | Yes, if severe and no response to psychotherapy | Yes | NS | Yes, if effective for woman’s depression | Sertraline, citalopram / Paroxetine, fluoxetine |

2.0 vs. 1.9–4.1 [18][19] |

Citalopram, sertraline, fluoxetine [19] | NS | BZD: 0.6 [20] AP: 0.4 [21] Quetiapine: 0.2 [21] |

| Finland [22] N-PPD | NS | Yes, in moderate-to-severe cases Psychotherapy first line |

Monitoring of response is important | NS | SSRIs / Paroxetine, fluoxetine, tricyclics |

1.6–4.0 [23] vs. 3.6* [24] |

NA | NS | BZD: 1.2* [25] AP: 0.8 [21] Quetiapine: 0.9 [21] |

| Germany [26] N-PPD | Yes, after individual risk benefit evaluation, individual disease history, preference and availability of alternative treatments | Yes, in moderate-to-severe cases. Abrupt discontinuation is discouraged. Psychotherapy first line |

Monotherapy if possible, lowest effective dose Continuous measurement of plasma levels |

NS | Sertraline, citalopram / Paroxetine, fluoxetine |

4.0 [27] vs. 0.4 (unpublished data) |

Amitriptyline, (es)citalopram, sertraline (unpublished data) | NS | BZD: 3.3 [25] AP: 0.3 [21] Quetiapine: 0.2 [21] |

| Italy [28] PMH-S |

Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment | Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment | NS | NS | NS | 3.3–4.4 [29] vs. 1.2–1.6 [29] |

Paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram [29] | Yes, BZD can be used | BZD: 1.4 [30] AP: 0.8 [31] Quetiapine: NA SAH: 0.4* [24] |

| Malta [32] PMH-S |

Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment; drug choice based on lowest risk, monotherapy if possible and at the lowest effective dose | Yes, after individual risk-benefit assessment; drug choice based on lowest risk, monotherapy if possible and at the lowest effective dose; previous response is considered | NS | If possible, switch paroxetine to other SSRI | Sertraline ¥; Fluoxetine / Paroxetine |

NA | Sertraline, fluoxetine (unpublished data) | BZD only short term for extreme anxiety or agitation; BZD should be avoided in late pregnancy | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| The Netherlands [33] PMH-S |

Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment | Yes, if woman is stable with medication | Yes, lowest effective dose; paroxetine preferably not >20 mg/day | If possible, switch paroxetine to other SSRI but pre-pregnancy | Sertraline ¥ / Paroxetine ¥ |

3.9 vs. 2.1 [34] |

Sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram [34] |

NS | BZD: 1.1 [25][35] AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Norway [36] PMH-S | Yes, if severe and with non-pharmacological therapy |

Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment. Psychotherapy first line. Abrupt discontinuation is discouraged. |

Yes, serum concentration | No | Choice based on prior drug response and its safety profile | 2.0 vs. 1.5 [37] |

(Es)citalopram, sertraline, venlafaxine [19] | NS | BZD: 0.9 [38] AP: 1.2 [21] Quetiapine: 0.3 [21] SAH: 1.0 [24] * |

| Poland [39] PMH-S |

Individual risk–benefit assessment to be made. **AD in 1 trimester should be avoided, and AD should be discontinued before delivery |

If severe depression or ongoing mild-to-moderate symptoms, AD should be considered. Gradual discontinuation if mild symptoms with psychotherapy. ** As for new depression. |

Monotherapy, lowest effective dose | Yes, switching an AD which is effective and offers fewer adverse effects | NS / Paroxetine |

- vs. 0.3 [24] * | NA | Yes, but do not offer BZD except for the short-term treatment of severe anxiety and agitation | BZD: 0.2–14.0 [24][25] * AP: NA Quetiapine: NA SAH: 0.4 [24] * |

| Serbia [40] N-PPD |

Yes, if severe after individual risk–benefit assessment |

Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment | Yes, serum concentration | NS | Fluoxetine, citalopram, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline / TCA |

- vs. 0.3 [24] * | (Es)citalopram, sertraline, mirtazapine, duloxetine (unpublished data) |

Yes, BZD |

BZD: 0.2–14.0 [24][25] * AP: NA Quetiapine: NA SAH: 0.4 [24] * |

| Spain [41] PMH-S |

Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment | Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment and based on individual drug response |

Monotherapy if possible, lowest effective dose; continuous measurement of plasma levels due to fluctuations in pregnancy is recommended | Yes, if lower risk to child and effective in mothers | SSRIs / Paroxetine, tricyclics, fluoxetine |

- vs. 0.5–0.8 [42][43] |

Paroxetine, citalopram, fluoxetine44 | Yes, but for acute symptoms for maximum 4 weeks | BZD: 1.9 [42] AP: 0.1 [43] Quetiapine: NA |

| United Kingdom [44][45] PMH-S |

Yes, particularly for moderate-to-severe depression, after discussing with the woman the risk–benefit assessment of AD; drug choice based on lowest risk, monotherapy if possible and at the lowest effective dose |

Yes, particularly for moderate-to-severe depression, after discussing with the woman the risk–benefit assessment of AD; monotherapy if possible and at the lowest effective dose | Yes, dosages may need to be adjusted in pregnancy | Option to be discussed with the woman but aim is to expose fetus to as few drugs as possible | Unspecified, choice based on prior drug response and its safety profile | 8.8–9.6 vs. 3.7 [29] |

Fluoxetine, citalopram [29] | Yes, with ADs. Do not offer BZD except for the short-term treatment of severe anxiety and agitation. | BZD: 1.2 * [25] AP: 0.3–4.6 [21][46] Quetiapine: 0.4 [21] |

2.3. Pharmacological Interventions for Treatment of Postpartum Depression

| Country, Publication Year, Type | Depression, Initiate or Continue AD | AD Intake by Time of BF | Switching AD | Preferred or Not Preferred AD | AD Use Postpartum (%) | Most Common ADs Postpartum | Treatment Co-Morbid Anxiety | Other Psychotropic Postpartum (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark [17] PMH-S | NS | No, but weight gain in infant should be monitored. Formula can be considered. | No, if the AD is effective and was taken in pregnancy | Sertraline, paroxetine / Fluoxetine, (es)citalopram, fluvoxamine, venlafaxine |

4.1 [29] | NA | NS | BZD: 1.3 [20] AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Finland [22] N-PPD |

As for non-pregnant adults, psychotherapy is recommended for mild symptoms | No, use of SSRI does not prevent BF | NS | SSRIs / Fluoxetine |

NA | NA | NS | BZD: 0.7–3.2 [47] AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Germany [26] N-PPD |

Yes, after risk–benefit analysis for mother and child and individual disease history, preference, and availability of alternative treatments | Yes, after risk–benefit analysis for mother and child | NS | SSRIs, tricyclics / NS |

NA | NA | NS | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Italy [28] PMH-S |

Yes, after risk–benefit analysis for mother and child | No, use of SSRI does not prevent BF | NS | NS / Fluoxetine |

2.5–3.4 [29] | NA | Yes, short-term acting BZD | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Latvia [48] PMH-S |

Yes, after risk–benefit analysis for mother and child in case of BF. For initiation of AD, start with lowest effective dose. | Assess whether dosage and regimen are compatible with BF | NS | SSRIs, sertraline / Fluoxetine |

NA | NA | Yes, mirtazapine or atypical AP; quetiapine for augmentation therapy. Olanzapine only at low doses. BZD should be avoided. | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Malta [32] PMH-S |

Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment; drug choice based on lowest risk, monotherapy if possible and at the lowest effective dose | Yes, after individual risk–benefit assessment; drug choice based on lowest risk, monotherapy if possible, and at the lowest effective dose, previous response is considered | NS | Iimipramine, nortriptyline, sertraline / Citalopram, fluoxetine |

NA | SSRIs e.g., sertraline, paroxetine (unpublished data) | Short-term BZD (caution in BF). Close monitoring of babies exposed to BZD via breastmilk. Diazepam should not be used while BF. | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| The Netherlands 33 PMH-S |

Yes, continue SSRI after delivery | Yes, BF is recommended | No, no evidence for switching | Paroxetine, sertraline / Fluoxetine, citalopram |

3.1 [34] | Paroxetine, citalopram, sertraline [34] |

NS | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Norway [36] PMH-S | Yes, if severe after individual risk–benefit assessment | NS | No | Sertraline, paroxetine / Doxepin, fluoxetine, citalopram |

1.0 [37] | NA | NS | BZD: 0.8 [37] AP: 0.2 [37] Quetiapine: NA |

| Poland [39] PMH-S |

Yes, initiate if severe and continue to prevent relapse. If history of severe depression or ongoing mild-to-moderate symptoms, AD should be considered. |

Yes, AD in one daily dose before the child’s longest sleep, and BF is recommended just before AD intake |

No, same treatment pattern should be used after delivery |

Sertraline, citalopram / Fluoxetine |

NA | NA | NA | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Serbia [40] N-PPD |

Yes, if severe after individual risk–benefit assessment |

NS | No | Fluoxetine | NA | Paroxetine (data unpublished) |

NS | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| Spain [41] PMH-S |

Yes, if severe after individual risk–benefit assessment | NS | NS | Nortriptyline, sertraline, paroxetine / Citalopram, fluoxetine |

NA | NA | NS | BZD: NA AP: NA Quetiapine: NA |

| United Kingdom [44][45] PMH-S |

Yes, particularly for moderate-to-severe depression after discussing with the woman of the risk–benefit assessment of AD; drug choice based on lowest risk, monotherapy if possible and at the lowest effective dose. | Consider risks and benefits of BF, which should generally be encouraged, but monitor baby for any adverse effects. | Option to be discussed with the woman, but aim is to expose the breastfed infant to as few drugs as possible. | Unspecified, choice based on prior drug response and its safety profile in breastfeeding. | 5.5–12.9 [29][46] | SSRI [49] | Yes, but do not offer BZD except for the short-term treatment of severe anxiety. BZD best avoided in BF if possible; use drug with shortest half-life. | BZD: NA AP: 0.4 [46] Quetiapine: NA |

2.4. Pharmacological Interventions for Antenatal or Postpartum Comorbid Anxiety and Use of Other Psychotropics

References

- Woody, C.A.; Ferrari, A.J.; Siskind, D.J.; Whiteford, H.A.; Harris, M.G. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 219, 86–92.

- Underwood, L.; Waldie, K.; D’Souza, S.; Peterson, E.R.; Morton, S. A review of longitudinal studies on antenatal and postnatal depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2016, 19, 711–720.

- Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R.; Dennis, C.L. The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal co-morbid anxiety and depression: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2017, 47, 2041–2053.

- Putnam, K.T.; Wilcox, M.; Robertson-Blackmore, E.; Sharkey, K.; Bergink, V.; Munk-Olsen, T.; Deligiannidis, K.M.; Payne, J.; Altemus, M.; Newport, J.; et al. Clinical phenotypes of perinatal depression and time of symptom onset: Analysis of data from an international consortium. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 477–485.

- Stein, A.; Pearson, R.M.; Goodman, S.H.; Rapa, E.; Rahman, A.; McCallum, M.; Howard, L.M.; Pariante, C.M. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014, 384, 1800–1819.

- Slomian, J.; Honvo, G.; Emonts, P.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health 2019, 15, 1745506519844044.

- Grigoriadis, S.; VonderPorten, E.H.; Mamisashvili, L.; Tomlinson, G.; Dennis, C.L.; Koren, G.; Steiner, M.; Mousmanis, P.; Cheung, A.; Radford, K.; et al. The impact of maternal depression during pregnancy on perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e321–e341.

- Gordon, H.; Nath, S.; Trevillion, K.; Moran, P.; Pawlby, S.; Newman, L.; Howard, L.M.; Molyneaux, E. Self-Harm, Self-Harm Ideation, and Mother-Infant Interactions: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2019, 80, 18m12708.

- Cantwell, R.; Clutton-Brock, T.; Cooper, G.; Dawson, A.; Drife, J.; Garrod, D.; Harper, A.; Hulbert, D.; Lucas, S.; McClure, J.; et al. Saving Mothers’ Lives: Reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006–2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG 2011, 118 (Suppl. 1), 1–203.

- Hendrick, V. Psychiatric Disorders in Pregnancy and the Postpartum: Principles and Treatment; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006.

- Molenaar, N.M.; Bais, B.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.P.; Mulder, C.L.; Howell, E.A.; Fox, N.S.; Rommel, A.S.; Bergink, V.; Kamperman, A.M. The international prevalence of antidepressant use before, during, and after pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of timing, type of prescriptions and geographical variability. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 264, 82–89.

- Lupattelli, A.; Spigset, O.; Bjornsdottir, I.; Hameen-Anttila, K.; Mardby, A.C.; Panchaud, A.; Juraski, R.G.; Rudolf, G.; Odalovic, M.; Drozd, M.; et al. Patterns and factors associated with low adherence to psychotropic medications during pregnancy—A cross-sectional, multinational web-based study. Depress. Anxiety 2015, 32, 426–436.

- Petersen, I.; Gilbert, R.E.; Evans, S.J.; Man, S.L.; Nazareth, I. Pregnancy as a major determinant for discontinuation of antidepressants: An analysis of data from The Health Improvement Network. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 979–985.

- Molenaar, N.M.; Kamperman, A.M.; Boyce, P.; Bergink, V. Guidelines on treatment of perinatal depression with antidepressants: An international review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 320–327.

- Van Damme, R.; Van Parys, A.S.; Vogels, C.; Roelens, K.; Lemmens, G.M.D. A mental health care protocol for the screening, detection and treatment of perinatal anxiety and depressive disorders in Flanders. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 128, 109865.

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. National Guidelines for Care for Depression and Anxiety Syndrome—Support for Control and Management. Available online: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/nationella-riktlinjer/2017-12-1.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2021).

- Middelboe, T.; Wøjdemann, K.; Bjergager, M.; Klindt Poulsen, B. Anvendelse af Psykofarmaka Ved Graviditet Og Amning—Kliniske Retningslinjer; Dansk Psykiatrisk Selskab; Dansk Selskab for Obstetrik og Gynækologi; Dansk Pædiatrisk Selskab og Dansk Selskab for Klinisk Farmakologi: Denmark, 27 October 2014; Available online: https://www.dpsnet.dk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/anvendelse_af_psykofarmaka_okt_2014.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- Jimenez-Solem, E.; Andersen, J.T.; Petersen, M.; Broedbaek, K.; Andersen, N.L.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Poulsen, H.E. Prevalence of antidepressant use during pregnancy in Denmark, a nation-wide cohort study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63034.

- Zoega, H.; Kieler, H.; Norgaard, M.; Furu, K.; Valdimarsdottir, U.; Brandt, L.; Haglund, B. Use of SSRI and SNRI Antidepressants during Pregnancy: A Population-Based Study from Denmark, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144474.

- Bais, B.; Munk-Olsen, T.; Bergink, V.; Liu, X. Prescription patterns of benzodiazepine and benzodiazepine-related drugs in the peripartum period: A population-based study. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112993.

- Reutfors, J.; Cesta, C.E.; Cohen, J.M.; Bateman, B.T.; Brauer, R.; Einarsdottir, K.; Engeland, A.; Furu, K.; Gissler, M.; Havard, A.; et al. Antipsychotic drug use in pregnancy: A multinational study from ten countries. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 220, 106–115.

- Current Clinical Care—Depression. Finnish Medical Association’s Duodecim and the Finnish Psychiatric Association. Available online: https://www.kaypahoito.fi/hoi50023#s13 (accessed on 30 June 2021).

- Gissler, M.; Artama, M.; Ritvanen, A.; Wahlbeck, K. Use of psychotropic drugs before pregnancy and the risk for induced abortion: Population-based register-data from Finland 1996–2006. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 383.

- Lupattelli, A.; Spigset, O.; Twigg, M.J.; Zagorodnikova, K.; Mardby, A.C.; Moretti, M.E.; Drozd, M.; Panchaud, A.; Hameen-Anttila, K.; Rieutord, A.; et al. Medication use in pregnancy: A cross-sectional, multinational web-based study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004365.

- Bais, B.; Molenaar, N.M.; Bijma, H.H.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Mulder, C.L.; Luik, A.I.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.P.; Kamperman, A.M. Prevalence of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs exposure before, during and after pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 269, 18–27.

- German S3 Guideline/National Health Care Guideline. Unipolar Depression; ÄZQ—Redaktion Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinien: Berlin, Germany, Peripartum Depression 2017; Chapter 3.9.1; pp. 151–159.

- Lewer, D.; O’Reilly, C.; Mojtabai, R.; Evans-Lacko, S. Antidepressant use in 27 European countries: Associations with sociodemographic, cultural and economic factors. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 221–226.

- Anniverno, R.; Bramante, A.; Petrilli, G.; Mencacci, C. Prevenzione, Diagnosi E Trattamento Della Psicopatologia Perinatale: Linee Guida Per Professionisti Della Salute; Osservatorio Nazionale sulla Salute della Donna: Milano, Italy, 2010.

- Charlton, R.A.; Jordan, S.; Pierini, A.; Garne, E.; Neville, A.J.; Hansen, A.V.; Gini, R.; Thayer, D.; Tingay, K.; Puccini, A.; et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor prescribing before, during and after pregnancy: A population-based study in six European regions. BJOG 2015, 122, 1010–1020.

- Lupattelli, A.; Picinardi, M.; Cantarutti, A.; Nordeng, H. Use and Intentional Avoidance of Prescribed Medications in Pregnancy: A Cross-Sectional, Web-Based Study among 926 Women in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3830.

- Barbui, C.; Conti, V.; Purgato, M.; Cipriani, A.; Fortino, I.; Rivolta, A.L.; Lora, A. Use of antipsychotic drugs and mood stabilizers in women of childbearing age with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: Epidemiological survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2013, 22, 355–361.

- Agius, R.; Felice, E.; Buhagia, R. Women with Mental Health Problems—During Pregnancy, Birth and the Postnatal Period. Malta. unpublished.

- Federatie Medisch Specialisten. SSRI-Gebruik en Zwangerschap. Available online: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/ssri_en_zwangerschap/ssri-gebruik_en_zwangerschap_-_startpagina.html (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Molenaar, N.M.; Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.P.; Bonsel, G.J. Dispensing patterns of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors before, during and after pregnancy: A 16-year population-based cohort study from the Netherlands. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 71–79.

- Radojcic, M.R.; El Marroun, H.; Miljkovic, B.; Stricker, B.H.C.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Verhulst, F.C.; White, T.; Tiemeier, H. Prenatal exposure to anxiolytic and hypnotic medication in relation to behavioral problems in childhood: A population-based cohort study. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2017, 61, 58–65.

- Thorbjørn, B.S.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Nordeng, H.; Nerum, H.; Lyng, S. Mental Helse i Svangerskapet. Veileder i Fødselshjelp 2020. Available online: https://www.legeforeningen.no/foreningsledd/fagmed/norsk-gynekologisk-forening/veiledere/veileder-i-fodselshjelp/ (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Engeland, A.; Bjorge, T.; Klungsoyr, K.; Hjellvik, V.; Skurtveit, S.; Furu, K. Trends in prescription drug use during pregnancy and postpartum in Norway, 2005 to 2015. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2018, 27, 995–1004.

- Riska, B.S.; Skurtveit, S.; Furu, K.; Engeland, A.; Handal, M. Dispensing of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-related drugs to pregnant women: A population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 70, 1367–1374.

- Samochowiec, J.; Rybakowski, J.; Galecki, P.; Szulc, A.; Rymaszewska, J.; Cubala, W.J.; Dudek, D. Recommendations of the Polish Psychiatric Association for treatment of affective disorders in women of childbearing age. Part I: Treatment of depression. Psychiatr. Pol. 2019, 53, 245–262.

- Milasinovic, G.; Vukicevic, D. Nacionalni Vodic Dobre Klinicke Orakse Za Djagnostikovanje i Lecenje Depresije; Ministarstvo zdravlja Republike Srbije: Belgrade, Serbia, 2011.

- García-Herrera, P.B.J.M.; Nogueras Morillas, E.V.; Muñoz Cobos, F.; Morales Asencio, J.M. Guía de Práctica Clínica Para el Tratamiento de la Depresión en Atención Primaria; Distrito Sanitario Málaga-UGC Salud Mental Hospital Regional Universitario “Carlos Haya”: Málaga, Spain, 2011.

- Lendoiro, E.; Gonzalez-Colmenero, E.; Concheiro-Guisan, A.; de Castro, A.; Cruz, A.; Lopez-Rivadulla, M.; Concheiro, M. Maternal hair analysis for the detection of illicit drugs, medicines, and alcohol exposure during pregnancy. Ther. Drug Monit. 2013, 35, 296–304.

- De Las Cuevas, C.; de la Rosa, M.A.; Troyano, J.M.; Sanz, E.J. Are psychotropics drugs used in pregnancy? Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007, 16, 1018–1023.

- NICE—National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance. 11 February 2020. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- McAllister-Williams, R.H.; Baldwin, D.S.; Cantwell, R.; Easter, A.; Gilvarry, E.; Glover, V.; Green, L.; Gregoire, A.; Howard, L.M.; Jones, I.; et al. British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. J. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 31, 519–552.

- Margulis, A.V.; Kang, E.M.; Hammad, T.A. Patterns of prescription of antidepressants and antipsychotics across and within pregnancies in a population-based UK cohort. Matern. Child Health J. 2014, 18, 1742–1752.

- Raitasalo, K.; Holmila, M.; Autti-Ramo, I.; Martikainen, J.E.; Sorvala, V.M.; Makela, P. Benzodiazepine use among mothers of small children: A register-based cohort study. Addiction 2015, 110, 636–643.

- Slimību Profilakses un Kontroles Centrs. Klīniskie Algoritmi un Pacientu Ceļi. Available online: https://www.spkc.gov.lv/lv/kliniskie-algoritmi-un-pacientu-celi (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Petersen, I.; Peltola, T.; Kaski, S.; Walters, K.R.; Hardoon, S. Depression, depressive symptoms and treatments in women who have recently given birth: UK cohort study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022152.