| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdelhakim Salem | + 3647 word(s) | 3647 | 2021-12-24 05:21:57 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 3647 | 2022-02-24 04:54:42 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | -9 word(s) | 3638 | 2022-02-24 05:00:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) comprises the majority of tumors in head and neck tissues. The prognosis of HNSCC has not significantly improved for decades, signifying the need for new diagnostic and therapeutic targets. Recent evidence suggests that oral microbiota is associated with carcinogenesis.

1. Introduction

2. Oral Microbiota in Head and Neck Cancers

| Study | Method | Sampling Type | Number of Samples | Microbiota Type | Microbiota Characterization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [15] | DNA-DNA hybridization | Whole unstimulated saliva through expectoration | 274 (229 OSCC-free controls; 45 OSCC) | 40 common oral bacteria were tested | Digoxigenin-labeled DNA using random primer technique was used |

| [16] | IHC | Tissue biopsy, PEFF | 15 (5 normal tissue; 10 GSCC) | P. gingivalis; S. gordonii | Rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:1000) |

| [17] | 16S rRNA PCR | Stimulated saliva | 5 (2 matched non-OSCC controls; 3 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | PCR primers were based on the V4–V5 hypervariable region |

| [18] | 16S rRNA PCR | DNA extraction from tissue biopsy samples | 20 (10 tumor-free tissues from OSCC patients; 10 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | PCR primers for V4–V5 hypervariable region; the eubacterial primers: prbac1 and prbac2 |

| [19] | 16S rRNA PCR | Swab samples from normal controls and lesions | 83 (49 normal controls; 34 OSCC/OPMDs) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | 16S rDNA V4 hypervariable region were sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform |

| [20] | 16S rRNA PCR | Oral rinse samples | 363 (242 normal controls; 121 OSCC/OPSCC cases) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The Illumina MiSeq primers targeting the V4 variable region |

| [21] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated saliva | 376 (127 normal controls; 124 OPMDs; 125 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (F515/ R806) targeting the V4 region of bacterial 16S rDNA |

| [22] | 16S rRNA PCR | Swab samples from normal controls and lesions | 27 (9 normal controls; 9 OPMDs; 9 cancer) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The primer pair D88/E94 produced near full length of 16S amplicons (targets V6–V9) |

| [23] | 16S rRNA PCR | Paired normal and tumoral resection specimens | 242 (121 tumor-free controls; 121 tumors) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | PCR of the V1–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene using the M13 primers |

| [24] | 16S rRNA PCR | Swab samples from normal controls and lesions | 80 (40 anatomically matched normal controls; 40 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (515F/926R) targeting the V4–V5 regions using Illumina MiSeq tool |

| [25] | 16S rRNA PCR | Mouth wash samples | 383 (254 matched normal controls; 129 HNSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (347F/803R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [26] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated saliva; peripheral blood (genotyping) | 289 (151 matched controls; 138 OSCC) | 20 species were included for case–control comparison | The PCR primer pair (341F/926R) targeting the V3–V5 regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [27] | 16S rRNA PCR | Oral rinse samples | 83 (20 normal controls; 11 high-risk; 52 tumors) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (515F/806R) targeting the V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA |

| [28] | 16S rRNA PCR | Tissue biopsy samples | 52 (27 oral fibroepithelial polyp as controls; 25 OSCC) |

Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (27FYMF/519R) targeting the V1-V3 regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [29] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated whole saliva | 30 (7 healthy controls; 9 dental compromised; 14 HNSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (341F/806R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [30] | 16S rRNA PCR | Oral rinse samples | 248 (51 healthy individuals; 197 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (16SF/16SR) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [31] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated saliva samples | 39 (OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primers (F515/R806) targeting the V4 region of the 16S rRNA |

| [32] | RNA amplification | Oral swab samples | 15 (4 OSCC; 11 OSCC-free sites/healthy individuals) | Active communities in tumor/tumor-free areas | Illumina adapter-specific primers were used to amplify the cDNA generated from mRNA |

| [33] | 16S rRNA PCR | Oral rinse samples | 38 (12 thyroid nodules as controls; 18 OSCC; 8 OPMDs) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (347F/803R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [34] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated saliva samples | 16 (4 healthy controls; 6 OSCC; 6 OPMDs) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primers (F515/R806) targeting the V4 gene region of the 16S rRNA |

| [35] | 16S rRNA PCR | Cytobrush (control); Tissue biopsy (OPSCC) | 52 (26 OPSCC; 26 controls) | P. melanogenica, F. naviforme, S. anginosus | Species-specific construct was designed that contained analyzed bacteria sequences |

| [36] | 16S rRNA PCR | Stimulated saliva samples | 140 (80 non-cancer controls; 60 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | PCR primers were developed for V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene |

| [37] | 16S rRNA PCR | Oral swabs from tumor and normal tissues | 100 (50 from non-tumor sites; 50 tumors) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (338F/806R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [38] | 16S rRNA PCR | Oral rinse samples; Tissue biopsy | 272 (136 non-tumor controls; 136 tumor samples) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (341F/806R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [39] | 16S rRNA PCR | Saliva samples | 994 (495 healthy controls; 499 patients with NPC) | Total bacterial diversity and ASVs prevalence | The PCR primer pair (341F/805R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [40] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated whole mouth fluid | 74 (23 healthy controls; 31 OSCC; 20 OPMDs) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (319F/806R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [41] | 16S rRNA PCR | Saliva samples; Tissue biopsy | 59 (18 non-tumor tissues;18 tumor tissue; 23 OSCC saliva) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | Adaptor-ligated 16S primers targeting the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene fragment |

| [42] | 16S rRNA PCR | Tissue biopsy samples | 48 (24 paracancerous control tissues; 24 tumor tissues) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (341F/806R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [43] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated saliva samples | 120 (64 healthy controls; 56 from cancer patients) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (341F/806R) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [44] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated saliva samples | 24 (8 healthy controls; 16 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (515F/806R) targeting the V4 region of the 16S rRNA was used |

| [45] | 16S rRNA PCR, IHC | Tissue biopsy samples | 212 (HNSCC) | F. nucleatum; gram-negative bacteria | A unique PCR primer for F. nucleatum; LPS monoclonal Mouse antibody (clone C8) |

| [46] | 16S rRNA PCR | Unstimulated saliva samples | 49 (24 healthy controls; 25 OSCC) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (16SF/16SR) targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA |

| [47] | 16S rRNA PCR | Tissue biopsy samples | 100 (50 paracancerous control tissues; 50 tumor tissues) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | A PCR primer pair targeting the V3–V4 variable regions of the 16S rRNA was used |

| [48] | 16S rRNA PCR | Oral swabs from tumor and normal tissues | 232 (116 contralateral normal tissues, 116 tumor tissues) | Total bacterial diversity and relative abundance | The PCR primer pair (515F/806R) targeting the V4 region of the 16S rRNA was used |

2.1. Oral Microbiota and OPMDs

2.2. Oral Microbiota and OSCC

2.3. Oral Microbiota in Other Types of HNSCC

2.4. Oral Dysbiosis and Tumor Progression in HNSCC

2.6. The Prognostic Value of Oral Microbiota in HNSCC

3. Summary

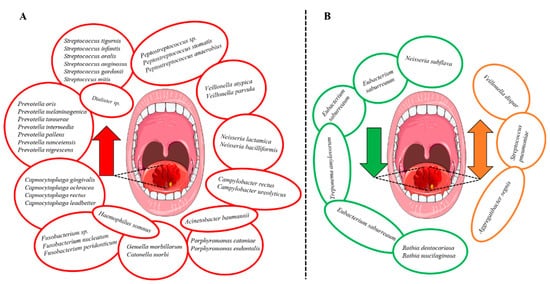

Bacterial genera that were increased in abundance in HNSCC patients included Fusobacterium [30][33][36][37][48], Peptostreptococcus [21][36][37][48], Alloprevotella [33][36][37], Capnocytophaga [36][37][48] and Prevotella [33][41][48]. Additionally, the species Prevotella melaninogenica [15][26], F. nucleatum [26][37][45][48] and Prevotella intermedia [26][37] were increased in HNSCC (Figure 3A). In contrast, certain bacterial genera including Streptococcus [30][33][37][41][48], Haemophilus [30][36], Rothia [36][37][41][44] and Veillonella [37][41][44] were decreased (Figure 3B). However, the findings were not always consistent since Veillonella dispar [26][46], Aggregatibacter segnis [37][46] and S. pneumoniae [41][48] were shown to be both increased and decreased in patients with HNSCC (Figure 3B). Survival outcomes were negatively associated with the decreased abundance of Haemophilus and Rothia. In contrast, genera Fusobacterium and species F. nucleatum were associated with improved survival and lower recurrence rates.

Oral microbiota were shown to be associated with cancers other than HNSCC including lung, colorectal and pancreatic cancers [9][11]. Importantly, carcinogenesis has recently been linked to periodontitis—a chronic inflammation largely mediated by oral dysbiosis [10]. In a recent meta-analysis, periodontitis and periodontal bacteria were associated with an increased incidence of cancer and poor survival rates. Interestingly, authors found that a higher cancer risk was associated with P. gingivalis and P. intermedia but not with F. nucleatum, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola or Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans [10]. Fusobacterium, specifically F. nucleatum, has a strong association to the tumorigenesis of colorectal cancer [49][50][51]. Genus Fusobacterium [30][33][36][37][48] and F. nucleatum [26][37][45][48] are connected to HNSCC. However, it was also proposed that abundance of Fusobacterium could have a favorable effect on HNSCC progression and survival [45][38]. Another well-studied species is P. gingivalis, an anaerobic bacteria that has been connected among others to pancreatic cancer [52][53] and OSCC [54][55][56]. Noteworthy, only one study showed a statistically significant evidence of the association between P. gingivalis and HNSCC using immunostaining on tissue samples [16]. This finding raises the question whether stimulated/unstimulated saliva, swabs or tissue samples would represent the most reliable method for analyzing oral microbiota in cancer patients. Data are, however, conflicting in this regard. While unstimulated saliva was considered inferior to stimulated saliva [57][58], another study showed that there are no major differences in their reliability [59].

References

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 92.

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 309–316.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Economopoulou, P.; De Bree, R.; Kotsantis, I.; Psyrri, A. Diagnostic Tumor Markers in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) in the Clinical Setting. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 827.

- Vigneswaran, N.; Williams, M.D. Epidemiologic Trends in Head and Neck Cancer and Aids in Diagnosis. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 26, 123–141.

- Mosaddad, S.A.; Tahmasebi, E.; Yazdanian, A.; Rezvani, M.B.; Seifalian, A.; Yazdanian, M.; Tebyanian, H. Oral microbial biofilms: An update. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 2005–2019.

- Arweiler, N.B.; Netuschil, L. The Oral Microbiota. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 902, 45–60.

- Kilian, M.; Chapple, I.L.C.; Hannig, M.; Marsh, P.D.; Meuric, V.; Pedersen, A.M.L.; Tonetti, M.S.; Wade, W.G.; Zaura, E. The oral microbiome—An update for oral healthcare professionals. Br. Dent. J. 2016, 221, 657–666.

- Irfan, M.; Delgado, R.Z.R.; Frias-Lopez, J. The Oral Microbiome and Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 591088.

- Xiao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Y.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y. The effect of periodontal bacteria infection on incidence and prognosis of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e19698.

- Teles, F.; Alawi, F.; Castilho, R.; Wang, Y. Association or Causation? Exploring the Oral Microbiome and Cancer Links. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 1411–1424.

- Schwabe, R.F.; Jobin, C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 800–812.

- Li, M.; Zhou, H.; Yang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles as a platform for biomedical applications: An update. J. Control. Release 2020, 323, 253–268.

- Guo, Q.; Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Chu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, H.; Liu, P.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Sequentially Triggered Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles for Macrophage Metabolism Modulation and Tumor Metastasis Suppression. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 13826–13838.

- Mager, D.; Haffajee, A.; Devlin, P.; Norris, C.; Posner, M.R.; Goodson, J. The salivary microbiota as a diagnostic indicator of oral cancer: A descriptive, non-randomized study of cancer-free and oral squamous cell carcinoma subjects. J. Transl. Med. 2005, 3, 27.

- Katz, J.N.; Onate, M.D.; Pauley, K.M.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Cha, S. Presence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in gingival squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2011, 3, 209–215.

- Pushalkar, S.; Mane, S.P.; Ji, X.; Li, Y.; Evans, C.; Crasta, O.R.; Morse, D.; Meagher, R.; Singh, A.; Saxena, D. Microbial diversity in saliva of oral squamous cell carcinoma. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 269–277.

- Pushalkar, S.; Ji, X.; Li, Y.; Estilo, C.; Yegnanarayana, R.; Singh, B.; Li, X.; Saxena, D. Comparison of oral microbiota in tumor and non-tumor tissues of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 144.

- Schmidt, B.L.; Kuczynski, J.; Bhattacharya, A.; Huey, B.; Corby, P.M. Changes in Abundance of Oral Microbiota Associated with Oral Cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106297.

- Börnigen, D.; Ren, B.; Pickard, R.; Li, J.; Ozer, E.; Hartmann, E.M.; Xiao, W.; Tickle, T.; Rider, J.; Gevers, D.; et al. Alterations in oral bacterial communities are associated with risk factors for oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17686.

- Lee, W.-H.; Chen, H.-M.; Yang, S.-F.; Wen-Liang, C.; Peng, C.-Y.; Tzu-Ling, Y.; Tsai, L.-L.; Wu, B.-C.; Hsin, C.-H.; Huang, C.-N.; et al. Bacterial alterations in salivary microbiota and their association in oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16540.

- Mok, S.F.; Karuthan, C.; Cheah, Y.K.; Ngeow, W.C.; Rosnah, Z.; Yap, S.F.; Ong, H.K.A. The oral microbiome community variations associated with normal, potentially malignant disorders and malignant lesions of the oral cavity. Malays. J. Pathol. 2017, 39, 1–15.

- Wang, H.; Funchain, P.; Bebek, G.; Altemus, J.; Zhang, H.; Niazi, F.; Peterson, C.; Lee, W.T.; Burkey, B.B.; Eng, C. Microbiomic differences in tumor and paired-normal tissue in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 14.

- Zhao, H.; Chu, M.; Huang, Z.; Yang, X.; Ran, S.; Hu, B.; Zhang, C.; Liang, J. Variations in oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11773.

- Hayes, R.B.; Ahn, J.; Fan, X.; Peters, B.A.; Ma, Y.; Yang, L.; Agalliu, I.; Burk, R.D.; Ganly, I.; Purdue, M.P.; et al. Association of Oral Microbiome with Risk for Incident Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 358–365.

- Hsiao, J.-R.; Chang, C.-C.; Lee, W.-T.; Huang, C.-C.; Ou, C.-Y.; Tsai, S.-T.; Chen, K.-C.; Huang, J.-S.; Wong, T.-Y.; Lai, Y.-H.; et al. The interplay between oral microbiome, lifestyle factors and genetic polymorphisms in the risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogens 2018, 39, 778–787.

- Lim, Y.; Fukuma, N.; Totsika, M.; Kenny, L.; Morrison, M.; Punyadeera, C. The Performance of an Oral Microbiome Biomarker Panel in Predicting Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancers. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2018, 8, 267.

- Perera, M.; Al-Hebshi, N.; Perera, I.; Ipe, D.; Ulett, G.; Speicher, D.; Chen, T.; Johnson, N. Inflammatory Bacteriome and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 725–732.

- Vesty, A.; Gear, K.; Biswas, K.; Radcliff, F.; Taylor, M.W.; Douglas, R.G. Microbial and inflammatory-based salivary biomarkers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2018, 4, 255–262.

- Yang, C.-Y.; Yeh, Y.-M.; Yu, H.-Y.; Chin, C.-Y.; Hsu, C.-W.; Liu, H.; Huang, P.-J.; Hu, S.-N.; Liao, C.-T.; Chang, K.-P.; et al. Oral Microbiota Community Dynamics Associated With Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Staging. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 862.

- Yang, S.-F.; Huang, H.-D.; Fan, W.-L.; Jong, Y.-J.; Chen, M.-K.; Huang, C.-N.; Kuo, Y.-L.; Hung, S.-I.; Su, S.-C. Compositional and functional variations of oral microbiota associated with the mutational changes in oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2018, 77, 1–8.

- Yost, S.; Stashenko, P.; Choi, Y.; Kukuruzinska, M.; Genco, C.A.; Salama, A.; Weinberg, E.; Kramer, C.D.; Frias-Lopez, J. Increased virulence of the oral microbiome in oral squamous cell carcinoma revealed by metatranscriptome analyses. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 10, 32.

- Ganly, I.; Yang, L.; Giese, R.A.; Hao, Y.; Nossa, C.W.; Morris, L.G.T.; Rosenthal, M.; Migliacci, J.; Kelly, D.; Tseng, W.; et al. Periodontal pathogens are a risk factor of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma, independent of tobacco and alcohol and human papillomavirus. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 775–784.

- Hashimoto, K.; Shimizu, D.; Hirabayashi, S.; Ueda, S.; Miyabe, S.; Oh-Iwa, I.; Nagao, T.; Shimozato, K.; Nomoto, S. Changes in oral microbial profiles associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma vs leukoplakia. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, e12445.

- Robayo, D.A.G.; Erira, H.A.T.; Jaimes, F.O.G.; Torres, A.M.; Galindo, A.I.C. Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Human Papilloma Virus Coinfection with Streptococcus anginosus. Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 626–633.

- Takahashi, Y.; Park, J.; Hosomi, K.; Yamada, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Iketani, S.; Kunisawa, J.; Mizuguchi, K.; Maeda, N.; et al. Analysis of oral microbiota in Japanese oral cancer patients using 16S rRNA sequencing. J. Oral Biosci. 2019, 61, 120–128.

- Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, H.J.; Zhang, C.P. The Oral Microbiota May Have Influence on Oral Cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 9, 476.

- Chen, Z.; Wong, P.Y.; Ng, C.W.K.; Lan, L.; Fung, S.; Li, J.W.; Cai, L.; Lei, P.; Mou, Q.; Wong, S.H.; et al. The Intersection between Oral Microbiota, Host Gene Methylation and Patient Outcomes in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3425.

- Debelius, J.W.; Huang, T.; Cai, Y.; Ploner, A.; Barrett, D.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, X.; Li, Y.; Liao, J.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Subspecies Niche Specialization in the Oral Microbiome Is Associated with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Risk. mSystems 2020, 5, e00065-20.

- Gopinath, D.; Menon, R.K.; Wie, C.C.; Banerjee, M.; Panda, S.; Mandal, D.; Behera, P.K.; Roychoudhury, S.; Kheur, S.; Botelho, M.G.; et al. Salivary bacterial shifts in oral leukoplakia resemble the dysbiotic oral cancer bacteriome. J. Oral Microbiol. 2021, 13, 1857998.

- Torralba, M.G.; Aleti, G.; Li, W.; Moncera, K.J.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yu, Y.; Masternak, M.M.; Golusinski, W.; Golusinski, P.; Lamperska, K.; et al. Oral Microbial Species and Virulence Factors Associated with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Microb. Ecol. 2020, 82, 1030–1046.

- Zhou, J.; Wang, L.; Yuan, R.; Yu, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, F.; Sun, G.; Dong, Q. Signatures of Mucosal Microbiome in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Identified Using a Random Forest Model. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 5353–5363.

- Zuo, H.-J.; Fu, M.R.; Zhao, H.-L.; Du, X.-W.; Hu, Z.-Y.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Ji, X.-Q.; Feng, X.-Q.; Zhumajiang, W.; Zhou, T.-H.; et al. Study on the Salivary Microbial Alteration of Men with Head and Neck Cancer and Its Relationship With Symptoms in Southwest China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 514943.

- Granato, D.C.; Neves, L.X.; Trino, L.D.; Carnielli, C.M.; Lopes, A.F.; Yokoo, S.; Pauletti, B.A.; Domingues, R.R.; Sá, J.O.; Persinoti, G.; et al. Meta-omics analysis indicates the saliva microbiome and its proteins associated with the prognosis of oral cancer patients. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2021, 1869, 140659.

- Neuzillet, C.; Marchais, M.; Vacher, S.; Hilmi, M.; Schnitzler, A.; Meseure, D.; Leclere, R.; Lecerf, C.; Dubot, C.; Jeannot, E.; et al. Prognostic value of intratumoral Fusobacterium nucleatum and association with immune-related gene expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7870.

- Rai, A.K.; Panda, M.; Das, A.K.; Rahman, T.; Das, R.; Das, K.; Sarma, A.; Kataki, A.C.; Chattopadhyay, I. Dysbiosis of salivary microbiome and cytokines influence oral squamous cell carcinoma through inflammation. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 137–152.

- Sarkar, P.; Malik, S.; Laha, S.; Das, S.; Bunk, S.; Ray, J.G.; Chatterjee, R.; Saha, A. Dysbiosis of Oral Microbiota During Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Development. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 614448.

- Su, S.-C.; Chang, L.-C.; Huang, H.-D.; Peng, C.-Y.; Chuang, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T.; Lu, M.-Y.; Chiu, Y.-W.; Chen, P.-Y.; Yang, S.-F. Oral microbial dysbiosis and its performance in predicting oral cancer. Carcinogenesis 2021, 42, 127–135.

- Kostic, A.D.; Chun, E.; Robertson, L.; Glickman, J.N.; Gallini, C.A.; Michaud, M.; Clancy, T.E.; Chung, D.C.; Lochhead, P.; Hold, G.L.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum Potentiates Intestinal Tumorigenesis and Modulates the Tumor-Immune Microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 207–215.

- Flanagan, L.; Schmid, J.; Ebert, M.; Soucek, P.; Kunicka, T.; Liška, V.; Bruha, J.; Neary, P.; DeZeeuw, N.; Tommasino, M.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum associates with stages of colorectal neoplasia development, colorectal cancer and disease outcome. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 33, 1381–1390.

- Castellarin, M.; Warren, R.L.; Freeman, J.D.; Dreolini, L.; Krzywinski, M.; Strauss, J.; Barnes, R.; Watson, P.; Allen-Vercoe, E.; Moore, R.A.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum infection is prevalent in human colorectal carcinoma. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 299–306.

- Fan, X.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Wu, J.; Peters, B.A.; Jacobs, E.J.; Gapstur, S.M.; Purdue, M.P.; Abnet, C.C.; Stolzenberg-Solomon, R.; Miller, G.; et al. Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: A population-based nested case-control study. Gut 2018, 67, 120–127.

- Michaud, D.S.; Izard, J.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.S.; You, D.-H.; Grote, V.A.; Tjonneland, A.; Dahm, C.C.; Overvad, K.; Jenab, M.; Fedirko, V.; et al. Plasma antibodies to oral bacteria and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large European prospective cohort study. Gut 2013, 62, 1764–1770.

- Ha, N.H.; Woo, B.H.; Kim, D.J.; Ha, E.S.; Choi, J.I.; Kim, S.J.; Park, B.S.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.R. Prolonged and repetitive exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis increases aggressiveness of oral cancer cells by promoting acquisition of cancer stem cell properties. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 9947–9960.

- Geng, F.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Zhao, H.; Pan, Y. Persistent Exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis Promotes Proliferative and Invasion Capabilities, and Tumorigenic Properties of Human Immortalized Oral Epithelial Cells. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 57.

- Ha, N.H.; Park, D.G.; Woo, B.H.; Kim, D.J.; Choi, J.I.; Park, B.S.; Kim, Y.D.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.R. Porphyromonas gingivalis increases the invasiveness of oral cancer cells by upregulating IL-8 and MMPs. Cytokine 2016, 86, 64–72.

- Belstrøm, D.; Sembler-Møller, M.L.; Grande, M.A.; Kirkby, N.; Cotton, S.L.; Paster, B.J.; Holmstrup, P. Microbial profile comparisons of saliva, pooled and site-specific subgingival samples in periodontitis patients. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182992.

- Gomar-Vercher, S.; Simon-Soro, A.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Almerich-Silla, J.M.; Mira, A. Stimulated and unstimulated saliva samples have significantly different bacterial profiles. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198021.

- Belstrøm, D.; Holmstrup, P.; Bardow, A.; Kokaras, A.; Fiehn, N.-E.; Paster, B.J. Comparative analysis of bacterial profiles in unstimulated and stimulated saliva samples. J. Oral Microbiol. 2016, 8, 30112.

- Cheng, A.; Schmidt, B.L. Management of the N0 Neck in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 20, 477–497.

- Chen, T.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Peng, W.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Tang, X.; Peng, Y.; Fu, X. Fusobacterium nucleatum promotes M2 polarization of macrophages in the microenvironment of colorectal tumours via a TLR4-dependent mechanism. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2018, 67, 1635–1646.

- Kumar, A.T.; Knops, A.; Swendseid, B.; Martinez-Outschoom, U.; Harshyne, L.; Philp, N.; Rodeck, U.; Luginbuhl, A.; Cognetti, D.; Johnson, J.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Tumor-Associated Macrophage Content in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 656.

- Troiano, G.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Adipietro, I.; Tepedino, M.; Santoro, R.; Laino, L.; Russo, L.L.; Cirillo, N.; Muzio, L.L. Prognostic significance of CD68+ and CD163+ tumor associated macrophages in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2019, 93, 66–75.