| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marco Colizzi | + 1438 word(s) | 1438 | 2022-02-10 07:44:36 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 1438 | 2022-02-14 03:26:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

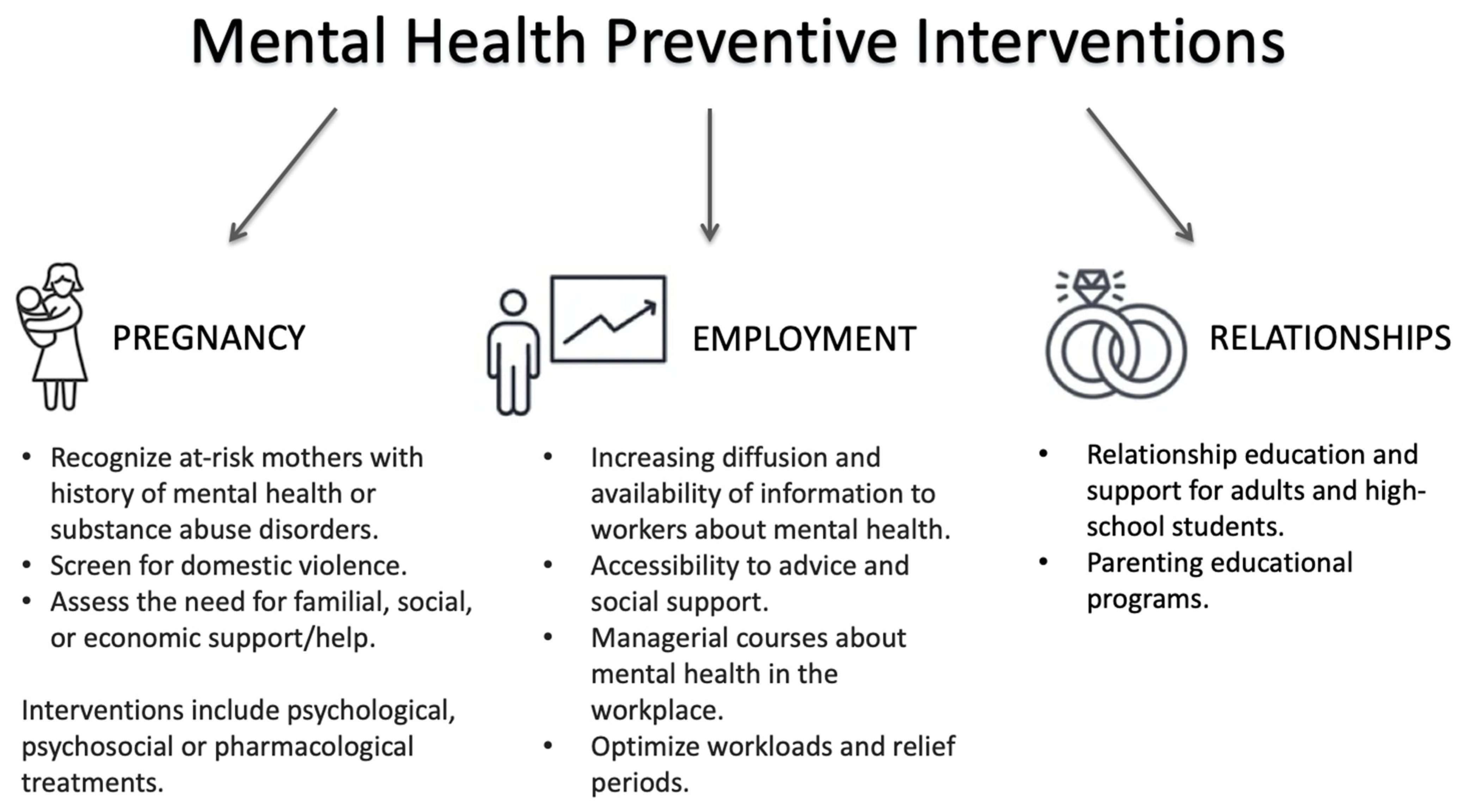

Among risk factors for mental health problems, there are individual, familiar, social, and healthcare factors. Individual factors include childhood adversities, which show gender differences in distribution rates. However, existing childhood abuse prevention programs are not gender-specific. Familiar factors for mental health problems include maternity issues and intimate partner violence, and for both, some gender-specific preventive interventions are available. Social risk factors for mental health problems are related to education, employment, discrimination, and relationships. They all display gender differences, but these differences are rarely taken into account in mental health prevention programs. Lastly, despite gender differences in mental health service use being widely known, mental health services appear to be slow in developing strategies that guarantee equal access to care for all individuals.

1. Introduction

2. Gender-Oriented Mental Health Prevention

3. Conclusions

References

- Trivedi, J.K.; Tripathi, A.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Moussaoui, D. Preventive Psychiatry: Concept Appraisal and Future Directions. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2014, 60, 321–329.

- Parry, T.S. The Effectiveness of Early Intervention: A Critical Review. J. Paediatr. Child Health 1992, 28, 343–346.

- WHO. Prevention of Mental Disorders. Effective Interventions and Policy Options; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Leavell, H.R.; Clark, E.G. Preventive Medicine for the Doctor in His Community: An Epidemiological Approach, 3rd ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1965.

- Shah, J.; Scott, J. Concepts and Misconceptions Regarding Clinical Staging Models. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016, 41, E83–E84.

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C. Ultra-High-Risk Paradigm: Lessons Learnt and New Directions. Evid. Based. Ment. Health 2018, 21, 131–133.

- Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Khan, M.N.; Mahmood, W.; Patel, V.; Bhutta, Z.A. Interventions for Adolescent Mental Health: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2016, 49–60, 754–762.

- Colizzi, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Prevention and Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Is It Time for a Multidisciplinary and Trans-Diagnostic Model for Care? Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 1–14.

- McGorry, P.D.; Mei, C. Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Progress and Future Directions. Evid.-Based Ment. Health 2018, 21, 182–184.

- Baumann, M.; Ebert, N.; Kurth, I.; Bacchus, C.; Overgaard, J. What Will Radiation Oncology Look like in 2050? A Look at a Changing Professional Landscape in Europe and Beyond. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 14, 1577–1585.

- Pietiläinen, E.; Roos, T.; Roos, O.; Rahkonen, S.; Heikkinen, K.; Seppä, H.; Ryynänen, J.P. Interactions of Smoking, Alcohol Use, Overweight and Physical Inactivity as Predictors of Cancer. Eur. J. Public Health 2018, 28, cky214-053.

- Hosang, G.M.; Bhui, K. Gender Discrimination, Victimisation and Women’s Mental Health. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 213, 682–684.

- Domínguez-Martínez, T.; Robles, R. Preventing Transphobic Bullying and Promoting Inclusive Educational Environments: Literature Review and Implementing Recommendations. Arch. Med. Res. 2019, 50, 543–555.

- Mustard, J.F. Brain Development, Child Development–Adult Health and Well-Being and Paediatrics. Paediatr. Child Health 1999, 4, 519–520.

- Maggi, S.; Irwin, L.J.; Siddiqi, A.; Hertzman, C. The Social Determinants of Early Child Development: An Overview. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2010, 46, 627–635.

- Fonagy, P.; Gergely, G.; Jurist, E.L.; Target, M. Attachment and Reflective Function: Their Role in Self-Organization. Affect Regul. Ment. Dev. Self 2018, 9, 23–64.

- Fox, S.E.; Levitt, P.; Nelson, C.A. How the Timing and Quality of Early Experiences Influence the Development of Brain Architecture. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 28–40.

- Black, M.M.; Walker, S.P.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Andersen, C.T.; DiGirolamo, A.M.; Lu, C.; McCoy, D.C.; Fink, G.; Shawar, Y.R.; Shiffman, J.; et al. Early Childhood Development Coming of Age: Science through the Life Course. Lancet 2017, 389, 77–90.

- Slopen, N.; Williams, D.R.; Fitzmaurice, G.M.; Gilman, S.E. Sex, Stressful Life Events, and Adult Onset Depression and Alcohol Dependence: Are Men and Women Equally Vulnerable? Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 73, 615–622.

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M. Stressful Life Events and Risk of Depression 25 Years Later: Race and Gender Differences. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 1–10.

- Kessler, R.C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K.R.; Walters, E.E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 593–602.

- Kessler, R.C.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Gruber, M.J.; Sampson, N.A.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alhamzawi, A.O.; Alonso, J.; Angermeyer, M.; et al. Childhood Adversities and Adult Psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br. J. Psychiatry 2010, 197, 378–385.

- Friedrich, M.J. Depression Is the Leading Cause of Disability around the World. JAMA 2017, 317, 1517.

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P.J.; Brinton, R.D.; Carrero, J.J.; DeMeo, D.L.; De Vries, G.J.; Epperson, C.N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S.L.; et al. Sex and Gender: Modifiers of Health, Disease, and Medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582.

- Rask, K.; Åstedt-Kurki, P.; Paavilainen, E.; Laippala, P. Adolescent Subjective Well-Being and Family Dynamics. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2003, 17, 129–138.

- Campos-Serna, J.; Ronda-Pérez, E.; Artazcoz, L.; Moen, B.E.; Benavides, F.G. Gender Inequalities in Occupational Health Related to the Unequal Distribution of Working and Employment Conditions: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2013, 12, 1–18.

- Williams, K. Has the Future of Marriage Arrived? A Contemporary Examination of Gender, Marriage, and Psychological Well-Being. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2003, 44, 470–487.

- Costa, R.; Dunsford, M.; Skagerberg, E.; Holt, V.; Carmichael, P.; Colizzi, M. Psychological Support, Puberty Suppression, and Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 2206–2214.

- Colizzi, M.; Costa, R.; Pace, V.; Todarello, O. Hormonal Treatment Reduces Psychobiological Distress in Gender Identity Disorder, Independently of the Attachment Style. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 3049–3058.

- Colizzi, M.; Costa, R.; Todarello, O. Transsexual Patients’ Psychiatric Comorbidity and Positive Effect of Cross-Sex Hormonal Treatment on Mental Health: Results from a Longitudinal Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 39, 65–73.