Whilst conventional echocardiography is considered the first line imaging modality for the clinical diagnosis of HCM, it is operator dependent and often limited by its acoustic windows and lack of tissue characterization

[9]. Conversely, CMR allows a more comprehensive and detailed evaluation of hypertrophy, with accurate measurements of wall thickness, chamber size, and distribution of hypertrophy (

Table 1). It is also capable of evaluating coronary flow reserve, contractility, and tissue perfusion, permitting the reproducible assessment of cardiac abnormalities

[10]. One of the significant advantages of CMR includes detailed anatomical assessment in different planes, providing a three-dimensional representation of anatomy

[11]. Thus, contouring the epicardial and endocardial borders allows the calculation of quantitative parameters, including consistent measurements of atrial and ventricular function and volumes. A typical CMR examination involves electrocardiographic (ECG) synchronized cine acquisitions, at a strength of 1.5 or 3T

[12]. There are three main techniques used in clinical CMR, which include spin echo imaging, gradient echo imaging, and flow velocity encoding

[11]. Steady-state free precession (SSFP), related to gradient echo imaging, involves generating high temporal and spatial resolution cine images, which are important for functional assessment

[13].

Table 1. There are several advantages of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) that include functional evaluation, morphological visualization, and risk stratification. There is also the added benefit of differentiating HCM from other similar processes that result in cardiac hypertrophy, such as amyloidosis, athlete’s heart, and hypertensive heart disease.

| Advantages of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| Identification of HCM phenotypes |

| Accurate quantification of maximal wall thickness |

| Assessment of co-existing valvulopathies |

| Volume analysis and quantification |

| Perfusion and strain analysis |

| Assessment of LVOT and cause |

| Offers differential diagnosis |

| Risk stratification through identification of fibrosis |

2.3. Late Gadolinium Enhancement

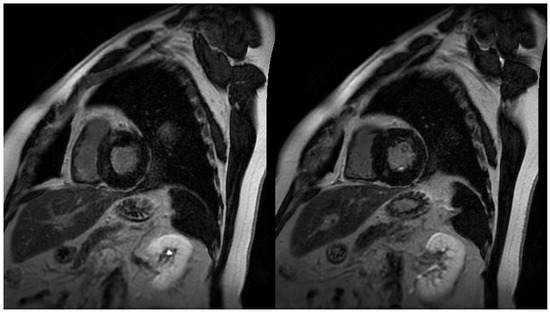

The identification and quantification of LGE is a valuable feature of CMR, changing the paradigm in how ischemic and non-ischemic myocardial diseases are assessed (

Figure 1). It represents myocardial fibrosis and is a predictor of both a higher mortality rate and the progression towards heart failure amongst HCM patients

[14]. The mean reported prevalence of LGE is 65%, but may be present in up to 86% of HCM patients

[7][15]. Typical patterns include localization to the mid-wall, located in segments with the greatest LVH, and at RV insertion points. Thus, peculiar patterns of LGE, during the assessment of LVH, can be attributed to other diagnoses that may include, but are not limited to, Anderson–Fabry disease or cardiac amyloidosis (CA). The distinction between the location of LGE includes the type of fibrosis, whereby intramural mid-wall LGE is considered a marker for replacement fibrosis, whilst LGE at RV insertion points suggests interstitial fibrosis

[16]. Replacement fibrosis increases diastolic dysfunction and ventricular stiffness

[17], and plays a role in the progression of heart failure.

Figure 1. Short axis images demonstrating patchy late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients. Common patterns identified in HCM patients include localization in segments with greatest left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), and right ventricular (RV) insertion points.

2.4. T1 and T2 Mapping

Early myocardial structural changes in cardiomyopathies are often elusive and indistinguishable. LGE was initially viewed as the gold standard for assessment of fibrosis in HCM. However, with the development of more sensitive techniques, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has described a paradigm shift towards the role of parametric mapping in assessing myocardial integrity

[18][19]. Therefore, T1, T2, and T2* mapping has become a routine part of the CMR exam, with changes in values showing early remodeling changes. T1 mapping provides the assessment of the total extent of expanded extracellular space

[20][21], and is thus emerging as a tool for the quantification of subtle fibrosis

[22][23]. Longitudinal relaxation time, which depends on T1, varies between tissues and pathological conditions. Whilst LGE signifies focal fibrosis and myocardial scar, native and post-contrast T1 mapping detects diffuse interstitial fibrosis

[24]. Moreover, subtle LGE enhancement may not be easily appreciable, and there may be errors in myocardial nulling during LGE assessment. Therefore, native and post-contrast T1 mapping has become a significant tool for prognostication in challenging cases. Extracellular volume (ECV), derived from T1 mapping, measures the proportion of extracellular space between myocytes.

T2 mapping, however, demonstrates myocardial or interstitial water content with variations in signal intensity being useful in differentiating between different cardiac diseases

[25]. In HCM, higher T2 values are reported, with the differences being accounted for on a structural level, which are purported to reflect myocyte degeneration, disarray, and replacement fibrosis

[26]. In addition, it frequently corresponds with LGE, which may explain the process of initial dysfunction in HCM and the subsequent progression to fibrosis

[27][28].

2.5. Strain Measurement

HCM patients often exhibit a hyperdynamic LV, and therefore the assessment of true LV function is of paramount importance. Similar to echocardiography, strain measurements include measurements in radial, circumferential, and longitudinal directions, reflecting both global and regional myocardial function. With a higher spatial resolution offered by CMR, it is argued that it displays a more superior and sensitive estimation of LV function than echocardiography. Here, LV strain is assessed using myocardial tissue tagging, where tagged CMR can assess regional myocardial mechanics at different time-points during the cardiac cycle

[29][30]. Several studies have reported HCM patients, despite a seemingly normal LV ejection fraction, as having globally reduced strain, which is associated with both increased mortality and heart failure events

[31][32]. The dysfunction of the LV in HCM is silent, and given myocardial contraction is heterogeneous, the different markers of strain assessment are useful in delineating the type of contractile dysfunction. For instance, the hypertrophied segments often exhibit reduced early diastolic strain rates

[33]. Such aggravation in myocardial integrity correlates biochemically, with elevated NT-proBNP and troponin T, and is also reflected by an increased likelihood of ventricular arrhythmias

[34][35].

2.6. Perfusion CMR

Microvascular dysfunction (MVD) is another common feature thought to be responsible for ischemia-mediated myocyte death in HCM, which is argued to result in replacement fibrosis and adverse LV remodeling. This is corroborated in postmortem studies that reveal the presence of ischemic damage in HCM hearts, without any significant coronary artery disease, that varies from acute to chronic fibrotic changes

[36][37]; other noteworthy changes include arteriolar dysplasia, without significant plaque formation

[17]. In order to assess the presence and impact of MVD, indirect measures such as myocardial perfusion reserve (MPR), derived by the ratio of myocardial blood flow (MBF) during maximal coronary vasodilation to MBF at rest, provides the means of estimating MVD. Adenosine stress perfusion MRI is highly sensitive and is the method that may assess such myocardial perfusion defects in HCM patients with suspected MVD

[38][39][40][41]. Perfusion defects are present in up to half of HCM patients, and is a predictor of clinical decline

[17].

More importantly, several studies have also shown a correlation between MVD and LGE burden

[42]. However, these perfusion defects may manifest themselves prior to the development of LGE

[43][44][45]. This was complemented by a recent study showing genotype-positive, phenotype-negative carriers of HCM in demonstrating both global and segmental perfusion defects, prior to the development of LGE

[46][47], therefore suggesting that microvascular abnormalities may precede the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis.

2.7. Microstructural Dysfunction

Microstructural changes are argued to precede macroscopic abnormalities in HCM, and in patients with normal wall thickness, and without any discernable scar, it is important to devise a technique that may appreciate these abnormalities and thus provide the viable markers necessary for the early detection of disease, screening of family members, and for prognostication. Cardiac diffusion tensor imaging (cDTI) is a method that allows the characterization of the myocardial microstructure and may provide such a solution. There are several parameters of measurement, including mean diffusivity (MD), fractional anisotropy (FA), voxel-wise helix angle (HA), and secondary eigenvector angle (E2A). MD measures the magnitude of diffusion in a given voxel, and is said to be increased in areas of interstitial fibrosis in HCM patients

[48]. FA measures the directional variability of diffusion in a given voxel, and is a measure of myocyte disarray, with low values suggesting adverse clinical outcomes, such as ventricular arrhythmias

[48][49][50].

2.8. Flow Imaging

The assessment of blood flow is important to the clinical evaluation of cardiovascular disease. Phase-contrast imaging allows the visualization and quantification of flow, and is widely used in cardiac imaging for the functional assessment of regional blood flow in the heart, across the valves, and in great vessels

[51][52][53]. It involves taking advantage of the direct relationship between blood flow velocity and phase of the MR signal, and through correction sequences and subtraction of unwanted signals, velocity encoded images are generated

[52][54]. Important basic functions of phase-contrast MRI include the estimation of cardiac output and evaluation of diastolic dysfunction. The measurement of diastolic dysfunction may be done by measuring the flow across the mitral valve, yielding information on early (E) and late or atrial (A) ventricular filling patterns

[11][54].

3. Conclusions

HCM is an inherited cardiomyopathy with a wide range of clinical presentations and long-term sequelae. Whilst many patients have an indolent course, a considerable number of patients are at an increased risk of SCD, heart failure, or tachyarrhythmias. Thus, imaging has come to play a central role in the diagnosis and prognostication of HCM. CMR is a widely employed tool that aids in the diagnosis and clinical management of HCM patients. Its capability in providing unique information on cardiac function, morphology, and tissue characterization has surpassed its own expectations, and with continued technological advancement, it is only a matter of time before pre-existing techniques are refined and newer methods are devised to even further characterize HCM.