| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antonio Ruggiero | + 3492 word(s) | 3492 | 2021-12-08 04:42:05 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 603 word(s) | 4095 | 2022-01-30 02:03:05 | | |

Video Upload Options

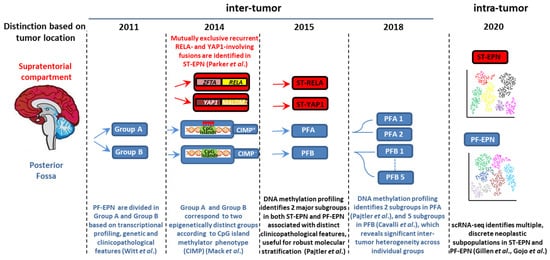

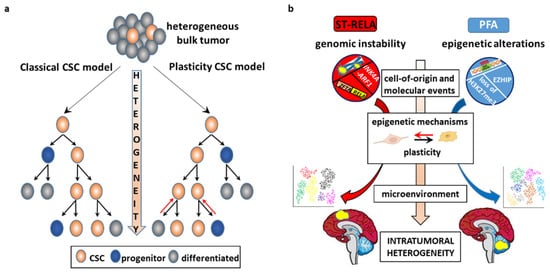

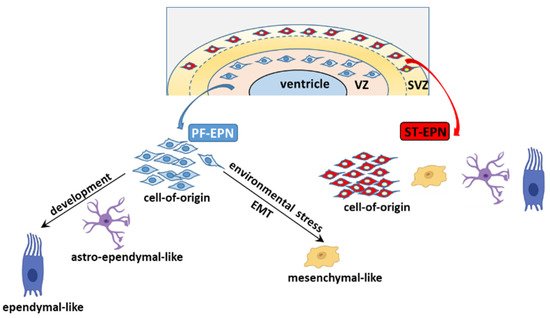

Intra-tumoral heterogeneity (ITH) is a complex multifaceted phenomenon that posits major challenges for the clinical management of cancer patients. Genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental factors are concurrent drivers of diversity among the distinct populations of cancer cells. ITH may also be installed by cancer stem cells (CSCs), that foster unidirectional hierarchy of cellular phenotypes or, alternatively, shift dynamically between distinct cellular states. Ependymoma (EPN), a molecularly heterogeneous group of tumors, shows a specific spatiotemporal distribution that suggests a link between ependymomagenesis and alterations of the biological processes involved in embryonic brain development. In children, EPN most often arises intra-cranially and is associated with an adverse outcome. Emerging evidence shows that EPN displays large intra-patient heterogeneity.

1. Introduction

2. Clinicopathological Characteristics of Pediatric Intracranial EPN

Approximately 70% of childhood EPNs occur in the PF, whereas 20% occur in the supratentorium. PFAs arise in younger children (<5 years) and are characterized by dysregulation of numerous cancer-related networks, such as angiogenesis, receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling, and cell cycle (Table 1) [18]. PFBs frequently occur in older children (5–18 years) and display many gains and losses of entire chromosomes [16], but dysregulation of a very restricted number of pathways controlling microtubule assembly and oxidative metabolism [18] (Table 1). More than two thirds of ST-EPNs harbor alternative ZFTA–RELA fusions [17] (Table 1), that lead to constitutively active NF-κB signaling, an established driver of solid tumors [21]. In addition, ST-RELA EPNs display other subgroup-specific genomic alterations, including frequent loss of chromosome 9 and homozygous INK4a-ARF (CDKN2a) deletions [16]. YAP1 fusions, the most common being YAP1-mastermind like domain containing 1 (MAMLD1), define the other clinically relevant subgroup of ST-EPN, rare tumors with relatively stable genomes, besides recurrent rearrangements involving YAP1 gene locus on chromosome 11 [16][22]. Compared to ST-RELA, YAP1-MAMLD1 tumors differ in demographic distribution (occurring mainly in children with a median age of 1.4 years vs. 8 years of RELA EPNs, and mostly restricted to female patients), anatomical location (intra-/periventricular in YAP1 vs. cerebral in RELA) and prognosis (favorable vs. unfavorable) [23].

| Molecular Group | ST-RELA | ST-YAP1 | PFA | PFB | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ST, cerebral | ST, intra-periventricular | PF | PF | [18][23] |

| Age | children/adolescents median age 8 years |

young children median age 1.4 years |

young children median age 3 years |

all age groups median age 30 years |

[16] |

| Gender | [16] | ||||

| Male | 65% | 25% | 65% | 41% | |

| Female | 35% | 75% | 35% | 59% | |

| Molecular events | |||||

| Genetic | chromothripsis ZFTA-RELA fusions CDKN2a deletion loss of chromosome 9 |

YAP1-fusions | balanced genome 1q gain 6q loss infrequent H3K27M substitution infrequent EZHIP mutations |

chromosomal instability | [16] [16][17] [16][24] [25] [26] |

| Epigenetic | CIMP positive DNA hypomethylation H3K27me3 loss EZHIP overexpression |

CIMP negative H3K27me3 retention |

[27] [28] [28][29] [26] |

||

| Pathogenic impact | NF-κB pathway cell cycle cell migration MAPK pathway |

Hippo pathway | angiogenesis RTK pathways cell cycle cell migration derepression of PRC2 target genes |

ciliogenesis oxidative metabolism |

[17][22] [16][18] [27] |

| Outcome | poor | favorable | poor | favorable | [16] |

There is increasing evidence of ST-EPNs with alternative gene fusions and ambiguous DNA methylation-based classification [30][31][32]. Pediatric supratentorial RELA fusion-negative EPNs show other fusion events, the majority involving ZFTA as a partner gene, such as ZFTA-mastermind like transcriptional coactivator 2 (MAML2) or ZFTA-nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (NCOA1). These tumors exhibit histopathological heterogeneity, no nuclear NF-κB expression, and epigenetic proximity to the RELA methylation class in some cases [33][34].

3. CSCs as a Source of ITH

3.1. The CSC Model

3.2. CSC-Driven Preclinical Models of EPN

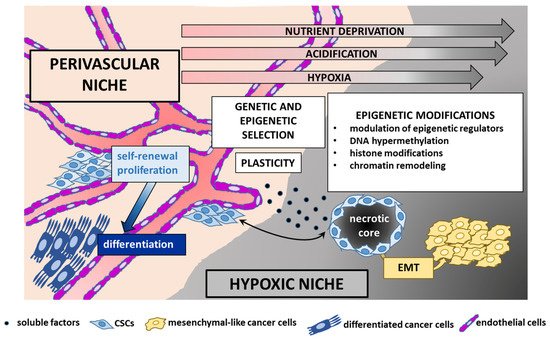

4. Determinants of ITH

4.1. Genetic ITH

4.2. Epigenetic ITH

4.3. TME, CSCs, and EPN

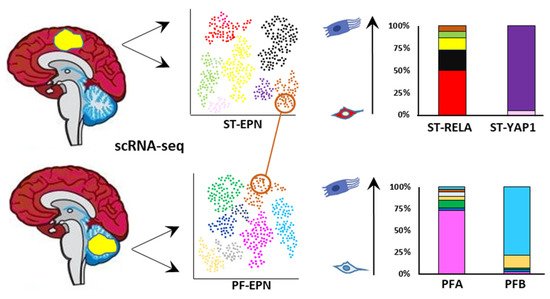

5. ITH of EPN: A Single-Cell Perspective

5.1. EPN Is Composed of Multiple Discrete Neoplastic Subpopulations

5.2. The Cell of Origin and Developmental Trajectories of EPN from an scRNA-seq Perspective

6. Therapeutic Applications

A potentially druggable pathway in PFA EPN is EZHIP, although direct targeting of EZHIP might prove difficult to achieve, because no enzymatic activity has hitherto been identified [105]. Numerous EZH2 inhibitors are currently undergoing phase 1 and phase 2 clinical testing in different tumors [106], and might have important implications for novel treatment protocols. Specifically, an advanced trial is evaluating the effectiveness of the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat in pediatric patients with recurrent EPN (NCT03213665).

References

- McGranahan, N.; Swanton, C. Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell 2017, 168, 613–628.

- McGranahan, N.; Swanton, C. Biological and Therapeutic Impact of Intratumor Heterogeneity in Cancer Evolution. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 15–26.

- Junttila, M.R.; de Sauvage, F.J. Influence of Tumour Micro-Environment Heterogeneity on Therapeutic Response. Nature 2013, 501, 346–354.

- Welch, D.R. Tumor Heterogeneity—A “Contemporary Concept” Founded on Historical Insights and Predictions. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4–6.

- Heppner, G.H. Tumor Heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 1984, 44, 2259–2265.

- Hinohara, K.; Polyak, K. Intratumoral Heterogeneity: More Than Just Mutations. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 569–579.

- Inda, M.-M.; Bonavia, R.; Mukasa, A.; Narita, Y.; Sah, D.W.Y.; Vandenberg, S.; Brennan, C.; Johns, T.G.; Bachoo, R.; Hadwiger, P.; et al. Tumor Heterogeneity Is an Active Process Maintained by a Mutant EGFR-Induced Cytokine Circuit in Glioblastoma. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1731–1745.

- Polyak, K.; Marusyk, A. Cancer: Clonal Cooperation. Nature 2014, 508, 52–53.

- Ricklefs, F.; Mineo, M.; Rooj, A.K.; Nakano, I.; Charest, A.; Weissleder, R.; Breakefield, X.O.; Chiocca, E.A.; Godlewski, J.; Bronisz, A. Extracellular Vesicles from High-Grade Glioma Exchange Diverse Pro-Oncogenic Signals That Maintain Intratumoral Heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2876–2881.

- Broekman, M.L.; Maas, S.L.N.; Abels, E.R.; Mempel, T.R.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Breakefield, X.O. Multidimensional Communication in the Microenvirons of Glioblastoma. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 482–495.

- Janiszewska, M.; Tabassum, D.P.; Castaño, Z.; Cristea, S.; Yamamoto, K.N.; Kingston, N.L.; Murphy, K.C.; Shu, S.; Harper, N.W.; Del Alcazar, C.G.; et al. Subclonal Cooperation Drives Metastasis by Modulating Local and Systemic Immune Microenvironments. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 879–888.

- Marusyk, A.; Janiszewska, M.; Polyak, K. Intratumor Heterogeneity: The Rosetta Stone of Therapy Resistance. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 471–484.

- Naffar-Abu Amara, S.; Kuiken, H.J.; Selfors, L.M.; Butler, T.; Leung, M.L.; Leung, C.T.; Kuhn, E.P.; Kolarova, T.; Hage, C.; Ganesh, K.; et al. Transient Commensal Clonal Interactions Can Drive Tumor Metastasis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5799.

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Gittleman, H.; Truitt, G.; Boscia, A.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, iv1–iv86.

- Pajtler, K.W.; Mack, S.C.; Ramaswamy, V.; Smith, C.A.; Witt, H.; Smith, A.; Hansford, J.R.; von Hoff, K.; Wright, K.D.; Hwang, E.; et al. The Current Consensus on the Clinical Management of Intracranial Ependymoma and Its Distinct Molecular Variants. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 5–12.

- Pajtler, K.W.; Witt, H.; Sill, M.; Jones, D.T.W.; Hovestadt, V.; Kratochwil, F.; Wani, K.; Tatevossian, R.; Punchihewa, C.; Johann, P.; et al. Molecular Classification of Ependymal Tumors across All CNS Compartments, Histopathological Grades, and Age Groups. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 728–743.

- Parker, M.; Mohankumar, K.M.; Punchihewa, C.; Weinlich, R.; Dalton, J.D.; Li, Y.; Lee, R.; Tatevossian, R.G.; Phoenix, T.N.; Thiruvenkatam, R.; et al. C11orf95-RELA Fusions Drive Oncogenic NF-ΚB Signalling in Ependymoma. Nature 2014, 506, 451–455.

- Witt, H.; Mack, S.C.; Ryzhova, M.; Bender, S.; Sill, M.; Isserlin, R.; Benner, A.; Hielscher, T.; Milde, T.; Remke, M.; et al. Delineation of Two Clinically and Molecularly Distinct Subgroups of Posterior Fossa Ependymoma. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 143–157.

- Suvà, M.L.; Tirosh, I. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing in Cancer: Lessons Learned and Emerging Challenges. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 7–12.

- Stuart, T.; Satija, R. Integrative Single-Cell Analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 257–272.

- Taniguchi, K.; Karin, M. NF-ΚB, Inflammation, Immunity and Cancer: Coming of Age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 309–324.

- Pajtler, K.W.; Wei, Y.; Okonechnikov, K.; Silva, P.B.G.; Vouri, M.; Zhang, L.; Brabetz, S.; Sieber, L.; Gulley, M.; Mauermann, M.; et al. YAP1 Subgroup Supratentorial Ependymoma Requires TEAD and Nuclear Factor I-Mediated Transcriptional Programmes for Tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3914.

- Andreiuolo, F.; Varlet, P.; Tauziède-Espariat, A.; Jünger, S.T.; Dörner, E.; Dreschmann, V.; Kuchelmeister, K.; Waha, A.; Haberler, C.; Slavc, I.; et al. Childhood Supratentorial Ependymomas with YAP1-MAMLD1 Fusion: An Entity with Characteristic Clinical, Radiological, Cytogenetic and Histopathological Features. Brain Pathol. Zurich Switz. 2019, 29, 205–216.

- Baroni, L.V.; Sundaresan, L.; Heled, A.; Coltin, H.; Pajtler, K.W.; Lin, T.; Merchant, T.E.; McLendon, R.; Faria, C.; Buntine, M.; et al. Ultra High-Risk PFA Ependymoma Is Characterized by Loss of Chromosome 6q. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, 1360–1370.

- Gessi, M.; Capper, D.; Sahm, F.; Huang, K.; von Deimling, A.; Tippelt, S.; Fleischhack, G.; Scherbaum, D.; Alfer, J.; Juhnke, B.-O.; et al. Evidence of H3 K27M Mutations in Posterior Fossa Ependymomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 132, 635–637.

- Pajtler, K.W.; Wen, J.; Sill, M.; Lin, T.; Orisme, W.; Tang, B.; Hübner, J.-M.; Ramaswamy, V.; Jia, S.; Dalton, J.D.; et al. Molecular Heterogeneity and CXorf67 Alterations in Posterior Fossa Group A (PFA) Ependymomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 211–226.

- Mack, S.C.; Witt, H.; Piro, R.M.; Gu, L.; Zuyderduyn, S.; Stütz, A.M.; Wang, X.; Gallo, M.; Garzia, L.; Zayne, K.; et al. Epigenomic Alterations Define Lethal CIMP-Positive Ependymomas of Infancy. Nature 2014, 506, 445–450.

- Bayliss, J.; Mukherjee, P.; Lu, C.; Jain, S.U.; Chung, C.; Martinez, D.; Sabari, B.; Margol, A.S.; Panwalkar, P.; Parolia, A.; et al. Lowered H3K27me3 and DNA Hypomethylation Define Poorly Prognostic Pediatric Posterior Fossa Ependymomas. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 366ra161.

- Panwalkar, P.; Clark, J.; Ramaswamy, V.; Hawes, D.; Yang, F.; Dunham, C.; Yip, S.; Hukin, J.; Sun, Y.; Schipper, M.J.; et al. Immunohistochemical Analysis of H3K27me3 Demonstrates Global Reduction in Group-A Childhood Posterior Fossa Ependymoma and Is a Powerful Predictor of Outcome. Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 134, 705–714.

- Fukuoka, K.; Kanemura, Y.; Shofuda, T.; Fukushima, S.; Yamashita, S.; Narushima, D.; Kato, M.; Honda-Kitahara, M.; Ichikawa, H.; Kohno, T.; et al. Significance of Molecular Classification of Ependymomas: C11orf95-RELA Fusion-Negative Supratentorial Ependymomas Are a Heterogeneous Group of Tumors. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018, 6, 134.

- Tamai, S.; Nakano, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Sabit, H.; Nobusawa, S.; Arai, Y.; Hama, N.; Totoki, Y.; Shibata, T.; Ichimura, K.; et al. Ependymoma with C11orf95-MAML2 Fusion: Presenting with Granular Cell and Ganglion Cell Features. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2021, 38, 64–70.

- Zheng, T.; Ghasemi, D.R.; Okonechnikov, K.; Korshunov, A.; Sill, M.; Maass, K.K.; Benites Goncalves da Silva, P.; Ryzhova, M.; Gojo, J.; Stichel, D.; et al. Cross-Species Genomics Reveals Oncogenic Dependencies in ZFTA/C11orf95 Fusion-Positive Supratentorial Ependymomas. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2230–2247.

- Tauziède-Espariat, A.; Siegfried, A.; Nicaise, Y.; Kergrohen, T.; Sievers, P.; Vasiljevic, A.; Roux, A.; Dezamis, E.; Benevello, C.; Machet, M.-C.; et al. Supratentorial Non-RELA, ZFTA-Fused Ependymomas: A Comprehensive Phenotype Genotype Correlation Highlighting the Number of Zinc Fingers in ZFTA-NCOA1/2 Fusions. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 9, 135.

- Zschernack, V.; Jünger, S.T.; Mynarek, M.; Rutkowski, S.; Garre, M.L.; Ebinger, M.; Neu, M.; Faber, J.; Erdlenbruch, B.; Claviez, A.; et al. Supratentorial Ependymoma in Childhood: More than Just RELA or YAP. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 455–466.

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem Cells, Cancer, and Cancer Stem Cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105–111.

- Prasetyanti, P.R.; Medema, J.P. Intra-Tumor Heterogeneity from a Cancer Stem Cell Perspective. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 41.

- Uchida, N.; Buck, D.W.; He, D.; Reitsma, M.J.; Masek, M.; Phan, T.V.; Tsukamoto, A.S.; Gage, F.H.; Weissman, I.L. Direct Isolation of Human Central Nervous System Stem Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 14720–14725.

- Singh, S.K.; Hawkins, C.; Clarke, I.D.; Squire, J.A.; Bayani, J.; Hide, T.; Henkelman, R.M.; Cusimano, M.D.; Dirks, P.B. Identification of Human Brain Tumour Initiating Cells. Nature 2004, 432, 396–401.

- Batlle, E.; Clevers, H. Cancer Stem Cells Revisited. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1124–1134.

- Gupta, P.B.; Fillmore, C.M.; Jiang, G.; Shapira, S.D.; Tao, K.; Kuperwasser, C.; Lander, E.S. Stochastic State Transitions Give Rise to Phenotypic Equilibrium in Populations of Cancer Cells. Cell 2011, 146, 633–644.

- Dirkse, A.; Golebiewska, A.; Buder, T.; Nazarov, P.V.; Muller, A.; Poovathingal, S.; Brons, N.H.C.; Leite, S.; Sauvageot, N.; Sarkisjan, D.; et al. Stem Cell-Associated Heterogeneity in Glioblastoma Results from Intrinsic Tumor Plasticity Shaped by the Microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1787.

- Wang, X.; Prager, B.C.; Wu, Q.; Kim, L.J.Y.; Gimple, R.C.; Shi, Y.; Yang, K.; Morton, A.R.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Reciprocal Signaling between Glioblastoma Stem Cells and Differentiated Tumor Cells Promotes Malignant Progression. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 514–528.e5.

- Lytle, N.K.; Barber, A.G.; Reya, T. Stem Cell Fate in Cancer Growth, Progression and Therapy Resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 669–680.

- Kondo, T. Glioblastoma-Initiating Cell Heterogeneity Generated by the Cell-of-Origin, Genetic/Epigenetic Mutation and Microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021.

- Muñoz, P.; Iliou, M.S.; Esteller, M. Epigenetic Alterations Involved in Cancer Stem Cell Reprogramming. Mol. Oncol. 2012, 6, 620–636.

- Servidei, T.; Meco, D.; Trivieri, N.; Patriarca, V.; Vellone, V.G.; Zannoni, G.F.; Lamorte, G.; Pallini, R.; Riccardi, R. Effects of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Blockade on Ependymoma Stem Cells in Vitro and in Orthotopic Mouse Models. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, E791–E803.

- Yu, L.; Baxter, P.A.; Voicu, H.; Gurusiddappa, S.; Zhao, Y.; Adesina, A.; Man, T.-K.; Shu, Q.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Zhao, X.-M.; et al. A Clinically Relevant Orthotopic Xenograft Model of Ependymoma That Maintains the Genomic Signature of the Primary Tumor and Preserves Cancer Stem Cells in Vivo. Neuro Oncol. 2010, 12, 580–594.

- Milde, T.; Kleber, S.; Korshunov, A.; Witt, H.; Hielscher, T.; Koch, P.; Kopp, H.-G.; Jugold, M.; Deubzer, H.E.; Oehme, I.; et al. A Novel Human High-Risk Ependymoma Stem Cell Model Reveals the Differentiation-Inducing Potential of the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor Vorinostat. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 122, 637–650.

- Amani, V.; Donson, A.M.; Lummus, S.C.; Prince, E.W.; Griesinger, A.M.; Witt, D.A.; Hankinson, T.C.; Handler, M.H.; Dorris, K.; Vibhakar, R.; et al. Characterization of 2 Novel Ependymoma Cell Lines with Chromosome 1q Gain Derived From Posterior Fossa Tumors of Childhood. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 76, 595–604.

- Bian, S.; Repic, M.; Guo, Z.; Kavirayani, A.; Burkard, T.; Bagley, J.A.; Krauditsch, C.; Knoblich, J.A. Genetically Engineered Cerebral Organoids Model Brain Tumor Formation. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 631–639.

- Sabnis, D.H.; Liu, J.-F.; Simmonds, L.; Blackburn, S.; Grundy, R.G.; Kerr, I.D.; Coyle, B. BLBP Is Both a Marker for Poor Prognosis and a Potential Therapeutic Target in Paediatric Ependymoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 2100.

- Meco, D.; Servidei, T.; Lamorte, G.; Binda, E.; Arena, V.; Riccardi, R. Ependymoma Stem Cells Are Highly Sensitive to Temozolomide in Vitro and in Orthotopic Models. Neuro Oncol. 2014, 16, 1067–1077.

- Servidei, T.; Meco, D.; Muto, V.; Bruselles, A.; Ciolfi, A.; Trivieri, N.; Lucchini, M.; Morosetti, R.; Mirabella, M.; Martini, M.; et al. Novel SEC61G-EGFR Fusion Gene in Pediatric Ependymomas Discovered by Clonal Expansion of Stem Cells in Absence of Exogenous Mitogens. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 5860–5872.

- Brennan, C.W.; Verhaak, R.G.W.; McKenna, A.; Campos, B.; Noushmehr, H.; Salama, S.R.; Zheng, S.; Chakravarty, D.; Sanborn, J.Z.; Berman, S.H.; et al. The Somatic Genomic Landscape of Glioblastoma. Cell 2013, 155, 462–477.

- Szerlip, N.J.; Pedraza, A.; Chakravarty, D.; Azim, M.; McGuire, J.; Fang, Y.; Ozawa, T.; Holland, E.C.; Huse, J.T.; Jhanwar, S.; et al. Intratumoral Heterogeneity of Receptor Tyrosine Kinases EGFR and PDGFRA Amplification in Glioblastoma Defines Subpopulations with Distinct Growth Factor Response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3041–3046.

- Schulte, A.; Günther, H.S.; Martens, T.; Zapf, S.; Riethdorf, S.; Wülfing, C.; Stoupiec, M.; Westphal, M.; Lamszus, K. Glioblastoma Stem-like Cell Lines with Either Maintenance or Loss of High-Level EGFR Amplification, Generated via Modulation of Ligand Concentration. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1901–1913.

- Negrini, S.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Halazonetis, T.D. Genomic Instability--an Evolving Hallmark of Cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 220–228.

- Siri, S.O.; Martino, J.; Gottifredi, V. Structural Chromosome Instability: Types, Origins, Consequences, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2021, 13, 3056.

- Stephens, P.J.; Greenman, C.D.; Fu, B.; Yang, F.; Bignell, G.R.; Mudie, L.J.; Pleasance, E.D.; Lau, K.W.; Beare, D.; Stebbings, L.A.; et al. Massive Genomic Rearrangement Acquired in a Single Catastrophic Event during Cancer Development. Cell 2011, 144, 27–40.

- Paulsen, T.; Kumar, P.; Koseoglu, M.M.; Dutta, A. Discoveries of Extrachromosomal Circles of DNA in Normal and Tumor Cells. Trends Genet. 2018, 34, 270–278.

- Verhaak, R.G.W.; Bafna, V.; Mischel, P.S. Extrachromosomal Oncogene Amplification in Tumour Pathogenesis and Evolution. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2019, 19, 283–288.

- Wu, S.; Turner, K.M.; Nguyen, N.; Raviram, R.; Erb, M.; Santini, J.; Luebeck, J.; Rajkumar, U.; Diao, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Circular EcDNA Promotes Accessible Chromatin and High Oncogene Expression. Nature 2019, 575, 699–703.

- Turner, K.M.; Deshpande, V.; Beyter, D.; Koga, T.; Rusert, J.; Lee, C.; Li, B.; Arden, K.; Ren, B.; Nathanson, D.A.; et al. Extrachromosomal Oncogene Amplification Drives Tumour Evolution and Genetic Heterogeneity. Nature 2017, 543, 122–125.

- deCarvalho, A.C.; Kim, H.; Poisson, L.M.; Winn, M.E.; Mueller, C.; Cherba, D.; Koeman, J.; Seth, S.; Protopopov, A.; Felicella, M.; et al. Discordant Inheritance of Chromosomal and Extrachromosomal DNA Elements Contributes to Dynamic Disease Evolution in Glioblastoma. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 708–717.

- Kim, H.; Nguyen, N.-P.; Turner, K.; Wu, S.; Gujar, A.D.; Luebeck, J.; Liu, J.; Deshpande, V.; Rajkumar, U.; Namburi, S.; et al. Extrachromosomal DNA Is Associated with Oncogene Amplification and Poor Outcome across Multiple Cancers. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 891–897.

- Nathanson, D.A.; Gini, B.; Mottahedeh, J.; Visnyei, K.; Koga, T.; Gomez, G.; Eskin, A.; Hwang, K.; Wang, J.; Masui, K.; et al. Targeted Therapy Resistance Mediated by Dynamic Regulation of Extrachromosomal Mutant EGFR DNA. Science 2014, 343, 72–76.

- Xu, K.; Ding, L.; Chang, T.-C.; Shao, Y.; Chiang, J.; Mulder, H.; Wang, S.; Shaw, T.I.; Wen, J.; Hover, L.; et al. Structure and Evolution of Double Minutes in Diagnosis and Relapse Brain Tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 123–137.

- Cortés-Ciriano, I.; Lee, J.J.-K.; Xi, R.; Jain, D.; Jung, Y.L.; Yang, L.; Gordenin, D.; Klimczak, L.J.; Zhang, C.-Z.; Pellman, D.S.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of Chromothripsis in 2,658 Human Cancers Using Whole-Genome Sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 331–341.

- Voronina, N.; Wong, J.K.L.; Hübschmann, D.; Hlevnjak, M.; Uhrig, S.; Heilig, C.E.; Horak, P.; Kreutzfeldt, S.; Mock, A.; Stenzinger, A.; et al. The Landscape of Chromothripsis across Adult Cancer Types. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2320.

- Brock, A.; Chang, H.; Huang, S. Non-Genetic Heterogeneity—A Mutation-Independent Driving Force for the Somatic Evolution of Tumours. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 336–342.

- Carja, O.; Plotkin, J.B. The Evolutionary Advantage of Heritable Phenotypic Heterogeneity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5090.

- Flavahan, W.A. Epigenetic Plasticity, Selection, and Tumorigenesis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020, 48, 1609–1621.

- Shen, H.; Laird, P.W. Interplay between the Cancer Genome and Epigenome. Cell 2013, 153, 38–55.

- Chalmers, Z.R.; Connelly, C.F.; Fabrizio, D.; Gay, L.; Ali, S.M.; Ennis, R.; Schrock, A.; Campbell, B.; Shlien, A.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. Analysis of 100,000 Human Cancer Genomes Reveals the Landscape of Tumor Mutational Burden. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 34.

- Capper, D.; Jones, D.T.W.; Sill, M.; Hovestadt, V.; Schrimpf, D.; Sturm, D.; Koelsche, C.; Sahm, F.; Chavez, L.; Reuss, D.E.; et al. DNA Methylation-Based Classification of Central Nervous System Tumours. Nature 2018, 555, 469–474.

- Gröbner, S.N.; Worst, B.C.; Weischenfeldt, J.; Buchhalter, I.; Kleinheinz, K.; Rudneva, V.A.; Johann, P.D.; Balasubramanian, G.P.; Segura-Wang, M.; Brabetz, S.; et al. The Landscape of Genomic Alterations across Childhood Cancers. Nature 2018, 555, 321–327.

- Huether, R.; Dong, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, G.; Parker, M.; Wei, L.; Ma, J.; Edmonson, M.N.; Hedlund, E.K.; Rusch, M.C.; et al. The Landscape of Somatic Mutations in Epigenetic Regulators across 1,000 Paediatric Cancer Genomes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3630.

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetic Determinants of Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a019505.

- Carter, B.; Zhao, K. The Epigenetic Basis of Cellular Heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 22, 235–250.

- Klemm, S.L.; Shipony, Z.; Greenleaf, W.J. Chromatin Accessibility and the Regulatory Epigenome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 207–220.

- Flavahan, W.A.; Gaskell, E.; Bernstein, B.E. Epigenetic Plasticity and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Science 2017, 357, eaal2380.

- Mack, S.C.; Hubert, C.G.; Miller, T.E.; Taylor, M.D.; Rich, J.N. An Epigenetic Gateway to Brain Tumor Cell Identity. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 10–19.

- Comet, I.; Riising, E.M.; Leblanc, B.; Helin, K. Maintaining Cell Identity: PRC2-Mediated Regulation of Transcription and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 803–810.

- Shen, L.; Kondo, Y.; Rosner, G.L.; Xiao, L.; Hernandez, N.S.; Vilaythong, J.; Houlihan, P.S.; Krouse, R.S.; Prasad, A.R.; Einspahr, J.G.; et al. MGMT Promoter Methylation and Field Defect in Sporadic Colorectal Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1330–1338.

- Hnisz, D.; Abraham, B.J.; Lee, T.I.; Lau, A.; Saint-André, V.; Sigova, A.A.; Hoke, H.A.; Young, R.A. Super-Enhancers in the Control of Cell Identity and Disease. Cell 2013, 155, 934–947.

- Brocks, D.; Assenov, Y.; Minner, S.; Bogatyrova, O.; Simon, R.; Koop, C.; Oakes, C.; Zucknick, M.; Lipka, D.B.; Weischenfeldt, J.; et al. Intratumor DNA Methylation Heterogeneity Reflects Clonal Evolution in Aggressive Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 798–806.

- Song, Y.; van den Berg, P.R.; Markoulaki, S.; Soldner, F.; Dall’Agnese, A.; Henninger, J.E.; Drotar, J.; Rosenau, N.; Cohen, M.A.; Young, R.A.; et al. Dynamic Enhancer DNA Methylation as Basis for Transcriptional and Cellular Heterogeneity of ESCs. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 905–920.e6.

- Bell, R.E.; Golan, T.; Sheinboim, D.; Malcov, H.; Amar, D.; Salamon, A.; Liron, T.; Gelfman, S.; Gabet, Y.; Shamir, R.; et al. Enhancer Methylation Dynamics Contribute to Cancer Plasticity and Patient Mortality. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 601–611.

- Mazor, T.; Pankov, A.; Song, J.S.; Costello, J.F. Intratumoral Heterogeneity of the Epigenome. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 440–451.

- Yang, D.; Holsten, T.; Börnigen, D.; Frank, S.; Mawrin, C.; Glatzel, M.; Schüller, U. Ependymoma Relapse Goes along with a Relatively Stable Epigenome, but a Severely Altered Tumor Morphology. Brain Pathol. 2021, 31, 33–44.

- Guo, M.; Peng, Y.; Gao, A.; Du, C.; Herman, J.G. Epigenetic Heterogeneity in Cancer. Biomark. Res. 2019, 7, 23.

- Mazor, T.; Pankov, A.; Johnson, B.E.; Hong, C.; Hamilton, E.G.; Bell, R.J.A.; Smirnov, I.V.; Reis, G.F.; Phillips, J.J.; Barnes, M.J.; et al. DNA Methylation and Somatic Mutations Converge on the Cell Cycle and Define Similar Evolutionary Histories in Brain Tumors. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 307–317.

- Magill, S.T.; Vasudevan, H.N.; Seo, K.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Choudhury, A.; John Liu, S.; Pekmezci, M.; Findakly, S.; Hilz, S.; Lastella, S.; et al. Multiplatform Genomic Profiling and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Identify Mechanisms Underlying Intratumor Heterogeneity in Meningioma. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4803.

- Liu, S.J.; Magill, S.T.; Vasudevan, H.N.; Hilz, S.; Villanueva-Meyer, J.E.; Lastella, S.; Daggubati, V.; Spatz, J.; Choudhury, A.; Orr, B.A.; et al. Multiplatform Molecular Profiling Reveals Epigenomic Intratumor Heterogeneity in Ependymoma. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 1300–1309.e5.

- Yuan, Y. Spatial Heterogeneity in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a026583.

- Gillies, R.J.; Brown, J.S.; Anderson, A.R.A.; Gatenby, R.A. Eco-Evolutionary Causes and Consequences of Temporal Changes in Intratumoural Blood Flow. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 576–585.

- Hoefflin, R.; Lahrmann, B.; Warsow, G.; Hübschmann, D.; Spath, C.; Walter, B.; Chen, X.; Hofer, L.; Macher-Goeppinger, S.; Tolstov, Y.; et al. Spatial Niche Formation but Not Malignant Progression Is a Driving Force for Intratumoural Heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–12.

- Hubert, C.G.; Rivera, M.; Spangler, L.C.; Wu, Q.; Mack, S.C.; Prager, B.C.; Couce, M.; McLendon, R.E.; Sloan, A.E.; Rich, J.N. A Three-Dimensional Organoid Culture System Derived from Human Glioblastomas Recapitulates the Hypoxic Gradients and Cancer Stem Cell Heterogeneity of Tumors Found In Vivo. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2465–2477.

- Estrella, V.; Chen, T.; Lloyd, M.; Wojtkowiak, J.; Cornnell, H.H.; Ibrahim-Hashim, A.; Bailey, K.; Balagurunathan, Y.; Rothberg, J.M.; Sloane, B.F.; et al. Acidity Generated by the Tumor Microenvironment Drives Local Invasion. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1524–1535.

- Korenchan, D.E.; Flavell, R.R. Spatiotemporal PH Heterogeneity as a Promoter of Cancer Progression and Therapeutic Resistance. Cancers 2019, 11, 1026.

- Bastola, S.; Pavlyukov, M.S.; Yamashita, D.; Ghosh, S.; Cho, H.; Kagaya, N.; Zhang, Z.; Minata, M.; Lee, Y.; Sadahiro, H.; et al. Glioma-Initiating Cells at Tumor Edge Gain Signals from Tumor Core Cells to Promote Their Malignancy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4660.

- Patel, A.P.; Tirosh, I.; Trombetta, J.J.; Shalek, A.K.; Gillespie, S.M.; Wakimoto, H.; Cahill, D.P.; Nahed, B.V.; Curry, W.T.; Martuza, R.L.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Highlights Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Primary Glioblastoma. Science 2014, 344, 1396–1401.

- Gillen, A.E.; Riemondy, K.A.; Amani, V.; Griesinger, A.M.; Gilani, A.; Venkataraman, S.; Madhavan, K.; Prince, E.; Sanford, B.; Hankinson, T.C.; et al. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing of Childhood Ependymoma Reveals Neoplastic Cell Subpopulations That Impact Molecular Classification and Etiology. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108023.

- Gojo, J.; Englinger, B.; Jiang, L.; Hübner, J.M.; Shaw, M.L.; Hack, O.A.; Madlener, S.; Kirchhofer, D.; Liu, I.; Pyrdol, J.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Cellular Hierarchies and Impaired Developmental Trajectories in Pediatric Ependymoma. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 44–59.e9.

- Jenseit, A.; Camgöz, A.; Pfister, S.M.; Kool, M. EZHIP: A New Piece of the Puzzle towards Understanding Pediatric Posterior Fossa Ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 1–13.

- Duan, R.; Du, W.; Guo, W. EZH2: A Novel Target for Cancer Treatment. J. Hematol. Oncol. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 104.

- Medeiros, M.; Candido, M.; Valera, E.; Brassesco, M. The Multifaceted NF-KB: Are There Still Prospects of Its Inhibition for Clinical Intervention in Pediatric Central Nervous System Tumors? Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 6161–6200.

- Armstrong, T.S.; Gilbert, M.R. Clinical Trial Challenges, Design Considerations, and Outcome Measures in Rare CNS Tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2021, 23, S30–S38.

- Donson, A.M.; Amani, V.; Warner, E.A.; Griesinger, A.M.; Witt, D.A.; Levy, J.M.M.; Hoffman, L.M.; Hankinson, T.C.; Handler, M.H.; Vibhakar, R.; et al. Identification of FDA-Approved Oncology Drugs with Selective Potency in High-Risk Childhood Ependymoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 1984–1994.

- Antonelli, R.; Jiménez, C.; Riley, M.; Servidei, T.; Riccardi, R.; Soriano, A.; Roma, J.; Martínez-Saez, E.; Martini, M.; Ruggiero, A.; et al. CN133, a Novel Brain-Penetrating Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, Hampers Tumor Growth in Patient-Derived Pediatric Posterior Fossa Ependymoma Models. Cancers 2020, 12, 1922.

- Mack, S.C.; Pajtler, K.W.; Chavez, L.; Okonechnikov, K.; Bertrand, K.C.; Wang, X.; Erkek, S.; Federation, A.; Song, A.; Lee, C.; et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Ependymoma as Informed by Oncogenic Enhancer Profiling. Nature 2018, 553, 101–105.

- Servidei, T.; Meco, D.; Martini, M.; Battaglia, A.; Granitto, A.; Buzzonetti, A.; Babini, G.; Massimi, L.; Tamburrini, G.; Scambia, G.; et al. The BET Inhibitor OTX015 Exhibits In Vitro and In Vivo Antitumor Activity in Pediatric Ependymoma Stem Cell Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1877.

- Lötsch, D.; Kirchhofer, D.; Englinger, B.; Jiang, L.; Okonechnikov, K.; Senfter, D.; Laemmerer, A.; Gabler, L.; Pirker, C.; Donson, A.M.; et al. Targeting Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors to Combat Aggressive Ependymoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 142, 339–360.

- Jain, S.U.; Do, T.J.; Lund, P.J.; Rashoff, A.Q.; Diehl, K.L.; Cieslik, M.; Bajic, A.; Juretic, N.; Deshmukh, S.; Venneti, S.; et al. PFA Ependymoma-Associated Protein EZHIP Inhibits PRC2 Activity through a H3 K27M-like Mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2146.

- Sievers, P.; Henneken, S.C.; Blume, C.; Sill, M.; Schrimpf, D.; Stichel, D.; Okonechnikov, K.; Reuss, D.E.; Benzel, J.; Maaß, K.K.; et al. Recurrent Fusions in PLAGL1 Define a Distinct Subset of Pediatric-Type Supratentorial Neuroepithelial Tumors. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 142, 827–839.

- Vega-Benedetti, A.F.; Saucedo, C.; Zavattari, P.; Vanni, R.; Zugaza, J.L.; Parada, L.A. PLAGL1: An Important Player in Diverse Pathological Processes. J. Appl. Genet. 2017, 58, 71–78.

- Arabzade, A.; Zhao, Y.; Varadharajan, S.; Chen, H.-C.; Jessa, S.; Rivas, B.; Stuckert, A.J.; Solis, M.; Kardian, A.; Tlais, D.; et al. ZFTA-RELA Dictates Oncogenic Transcriptional Programs to Drive Aggressive Supratentorial Ependymoma. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2200–2215.