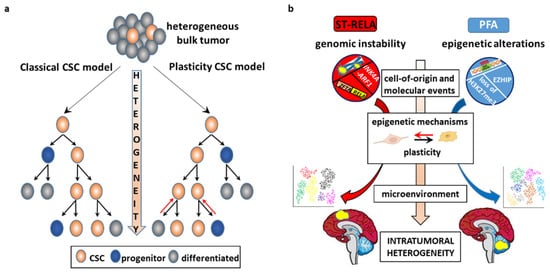

Intra-tumoral heterogeneity (ITH) is a complex multifaceted phenomenon that posits major challenges for the clinical management of cancer patients. Genetic, epigenetic, and microenvironmental factors are concurrent drivers of diversity among the distinct populations of cancer cells. ITH may also be installed by cancer stem cells (CSCs), that foster unidirectional hierarchy of cellular phenotypes or, alternatively, shift dynamically between distinct cellular states. Ependymoma (EPN), a molecularly heterogeneous group of tumors, shows a specific spatiotemporal distribution that suggests a link between ependymomagenesis and alterations of the biological processes involved in embryonic brain development. In children, EPN most often arises intra-cranially and is associated with an adverse outcome. Emerging evidence shows that EPN displays large intra-patient heterogeneity.

- intra-tumoral heterogeneity

- ependymoma

- genetics

- epigenetics

- tumor microenvironment

- cancer stem cells

1. Introduction

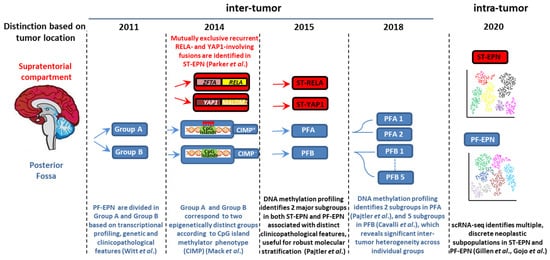

2. Clinicopathological Characteristics of Pediatric Intracranial EPN

Approximately 70% of childhood EPNs occur in the PF, whereas 20% occur in the supratentorium. PFAs arise in younger children (<5 years) and are characterized by dysregulation of numerous cancer-related networks, such as angiogenesis, receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling, and cell cycle (Table 1) [18][25]. PFBs frequently occur in older children (5–18 years) and display many gains and losses of entire chromosomes [16][23], but dysregulation of a very restricted number of pathways controlling microtubule assembly and oxidative metabolism [18][25] (Table 1). More than two thirds of ST-EPNs harbor alternative ZFTA–RELA fusions [17][24] (Table 1), that lead to constitutively active NF-κB signaling, an established driver of solid tumors [21][38]. In addition, ST-RELA EPNs display other subgroup-specific genomic alterations, including frequent loss of chromosome 9 and homozygous INK4a-ARF (CDKN2a) deletions [16][23]. YAP1 fusions, the most common being YAP1-mastermind like domain containing 1 (MAMLD1), define the other clinically relevant subgroup of ST-EPN, rare tumors with relatively stable genomes, besides recurrent rearrangements involving YAP1 gene locus on chromosome 11 [16][22][23,39]. Compared to ST-RELA, YAP1-MAMLD1 tumors differ in demographic distribution (occurring mainly in children with a median age of 1.4 years vs. 8 years of RELA EPNs, and mostly restricted to female patients), anatomical location (intra-/periventricular in YAP1 vs. cerebral in RELA) and prognosis (favorable vs. unfavorable) [23][40].

| Molecular Group | ST-RELA | ST-YAP1 | PFA | PFB | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ST, cerebral | ST, intra-periventricular | PF | PF | [18][23] |

| Age | children/adolescents median age 8 years |

young children median age 1.4 years |

young children median age 3 years |

all age groups median age 30 years |

[16] |

| Gender | [16] | ||||

| Male | 65% | 25% | 65% | 41% | |

| Female | 35% | 75% | 35% | 59% | |

| Molecular events | |||||

| Genetic | chromothripsis ZFTA-RELA fusions CDKN2a deletion loss of chromosome 9 |

YAP1-fusions | balanced genome 1q gain 6q loss infrequent H3K27M substitution infrequent EZHIP mutations |

chromosomal instability | [16] [16][17] [16][24] [25] [26] |

| Epigenetic | CIMP positive DNA hypomethylation H3K27me3 loss EZHIP overexpression |

CIMP negative H3K27me3 retention |

[27] [28] [28][29] [26] |

||

| Pathogenic impact | NF-κB pathway cell cycle cell migration MAPK pathway |

Hippo pathway | angiogenesis RTK pathways cell cycle cell migration derepression of PRC2 target genes |

ciliogenesis oxidative metabolism |

[17][22] [16][18] [27] |

| Outcome | poor | favorable | poor | favorable | [16] |

There is increasing evidence of ST-EPNs with alternative gene fusions and ambiguous DNA methylation-based classification [30][31][32][41,42,43]. Pediatric supratentorial RELA fusion-negative EPNs show other fusion events, the majority involving ZFTA as a partner gene, such as ZFTA-mastermind like transcriptional coactivator 2 (MAML2) or ZFTA-nuclear receptor coactivator 1 (NCOA1). These tumors exhibit histopathological heterogeneity, no nuclear NF-κB expression, and epigenetic proximity to the RELA methylation class in some cases [33][34][44,45].

3. CSCs as a Source of ITH

3.1. The CSC Model

3.2. CSC-Driven Preclinical Models of EPN

3.2. CSC-Driven Preclinical Models of EPN

Cell lines have been established from EPN surgical samples by selection of the CSC component in NS-promoting conditions [46][47][48][49][72,73,74,75]. NS models mimic a 3D structure, which resembles the tumor microenvironment (TME) more faithfully than 2D cultures, preserving cell variability [50][76]. Compared to cell lines grown as monolayers, EPN 3D cultures transplanted in the mouse brain show better fidelity to the original tumor in terms of genetic, transcriptomic, and histopathological characteristics [48][49][74,75]. Drug treatment of patient-derived EPN cell lines results in preferential depletion of a stem-like cell population with a tumor-initiating property, as shown by a decrease in NSC markers, increase in differentiation-associated markers, and reduction in tumorigenicity in ex vivo transplantation assays [46][48][72,74]. Specific targeting of BLBP by PPAR antagonists lessens cell migration and invasion and promotes chemoresistance in vitro [51][77]. In comparison with EPN stem-like cells, differentiated cells are less sensitive to temozolomide because of differentiation-induced upregulation of MGMT [52][78], although others have also reported temozolomide resistance in undifferentiated EPN SCs [48][74].4. Determinants of ITH

4.1. Genetic ITH

4.2. Epigenetic ITH

Variable phenotypes of cancer cells can also be mediated by epigenetic, transcriptional, and microenvironmental changes without concomitant genetic mutations. Non-genetic ITH is far more dynamic than genetic heterogeneity and is therefore increasingly recognized as a driving force of tumor evolution [70][71][112,113]. The term “epigenetic” describes the covalent modifications of DNA and histones that affect gene expression without intrinsic changes in the DNA sequence through modulation of the chromatin structure [70][112]. Epigenetic changes are inherited by offspring cells just like genetic alterations and provide an additional pool of selectable traits. An interplay between genetic and epigenetic alterations occurs in virtually all tumor types, where epigenetic lesions may precede or arise simultaneously with genetic mutations, or conversely be a consequential event [72][73][10,114]. PBTs display an overall low mutational burden, but there are a number of epigenetic dysregulations [74][75][76][115,116,117] that can drive tumorigenesis even in the absence of highly recurrent driver mutations, CIMP-positive PFA being a prominent example. Most of the few recurrent mutations of PBTs target epigenetic regulatory genes, such as H3.3A, ATRX, and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) [77][118]. Epigenome regulation of intercellular heterogeneous gene expression is a dynamic condition between transcriptionally active and repressive chromatin states by virtue of cell-to-cell variation in DNA methylation at enhancers and promoters, covalent histone modifications [78][33], nucleosome positioning [79][121], and chromatin accessibility [80][122]. Prominent alterations of DNA methylation in cancers, including high-risk PFAs, are focal gains at normally unmethylated CpG islands and promoter regions, that heritably silence hundreds of genes that counteract tumor development, outnumbering gene mutations [81][82][123,124]. Posttranslational covalent histone modifications include methylation or acetylation at histone tails, such as H3K27me3 and H3K27ac, markers of repressed and active transcription, respectively [73][114]. H3K27 trimethylation is mediated by the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) via the methyltransferase activity of the PRC2 catalytic subunit EZH2 [83][125]. Epigenetic ITH has primarily been assessed focusing on DNA methylation, because of its stability and mitotic heritability, and is found in regulatory regions that control the transcription of associated genes, contributing to gene expression heterogeneity relevant to cell identity and disease processes [81][84][85][86][123,126,127,128]. High epigenetic heterogeneity at enhancers has been reported in ESCs [87][129] and during progression from normal tissues to primary tumors and to metastases with a cancer-specific pattern [88][130], which indicates that enhancer DNA methylation may be primed to respond to microenvironmental cues and to increase cancer cell plasticity. In temporally distinct tumor specimens, DNA methylation levels are reported to be increased, equal, or decreased in primary vs. relapsed tumors [89][131], maybe because of variable epigenetic clonal dynamics in different cancers. Compared to primary EPNs, relapsed EPNs display neither significant differences in DNA methylation profiles nor in H3K27me3 levels, whereas major changes occur at CpG islands that show higher methylations in relapsed ST-RELA and PFA EPNs [90][132]. Spatiotemporal epigenetic heterogeneity in distinct areas of the same tumor has been described in a wide range of cancers and allows for building the evolutionary history of the tumor alongside genetic heterogeneity. Comparison between phylogenetic and epigenetic trees has usually shown similar and integrated patterns, which suggests a codependency of genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in tumor progression [89][91][131,133]. In primary low-grade gliomas and matched recurrent HGG, cell cycle genes are epigenetically upregulated through promoter hypomethylation during tumor progression, in parallel with genetic mutations that affect cell cycle checkpoints [92][134]. Multiplatform molecular profiling of spatially distinct meningioma shows regional alterations in chromosome structure that underpin clonal transcriptomic, epigenomic, and histopathologic signatures [93][135]. DNA methylation and RNA sequencing of six topographically distinct samples from one ST-RELA tumor reveal significant transcriptional and epigenetic heterogeneity [94][136]. Remarkably, the expression of the subgroup-specific markers L1CAM, CCND1, ZFTA, and RELA is similar across the sections, whereas DNA methylation-based and gene expression variability define three geographically distinct clusters enriched in stem-like, neuronal differentiation, and mature microglia signatures that recapitulate brain development.4.3. TME, CSCs, and EPN

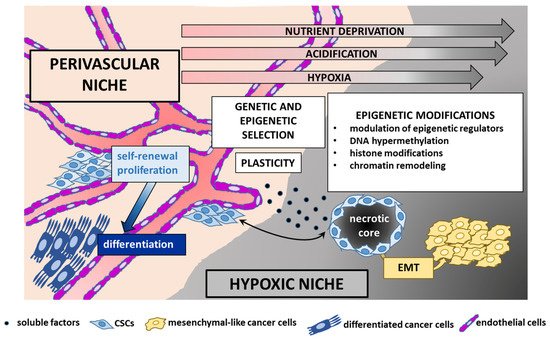

The epigenome stands at the intersection of the genome and TME. Unlike genetic alterations, epigenetic modifications are reversible and less consistently transmitted through mitosis, and therefore play a major role in opportunistic adaptation to spatiotemporal fluctuations of the TME [3][95][3,152]. Whereas in healthy tissues the environment acts as the main barrier to counteract cancer initiation, in tumor tissues neoplastic cells subvert this organized architecture into a deranged tumor-sustaining milieu. These changes include matrix remodeling, development of tumor vasculature networks, recruitment of stromal and immune cells, and interactions between tumor and normal cells as well as between functionally different tumor subpopulations [10][17]. The complex tumor architecture creates topographical constraints, changeable blood flow [96][153], and heterogeneous microenvironmental conditions with a combinatorial dynamic of contextual cues that trigger a variety of signaling pathways and regulatory networks [6][13]. This paradigmatically occurs at the tumor core and tumor/host interface. Although region-specific driver mutations have been documented [97][154], contextual factors are equally important in shaping the zonal pattern, with high proliferation, signaling activities and invasion-promoting properties almost exclusively restricted to the leading edge of the tumor as opposed to a quiescent, apoptotic, and therapy-resistant phenotype predominating in the center. These distinct intrinsic signatures and phenotypes are driven by hypoxic [98][155] and/or acidic microenvironmental gradients [99][100][156,157] and paracrine cross-talk [101][158] between the distinct tumor populations. Microenvironmental variability promotes commonly observed phenotypic cellular properties, such as stemness and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). There is an intricate interaction between CSCs and their microenvironment. CSCs are actively engaged in shaping their own supportive niche, but are in turn regulated by exogenous signals that affect their epigenome and cellular state [41][82][9,124] shaping tumor heterogeneity and evolution. Examples of the interconnections between EPN and TME are given below (Figure 34).

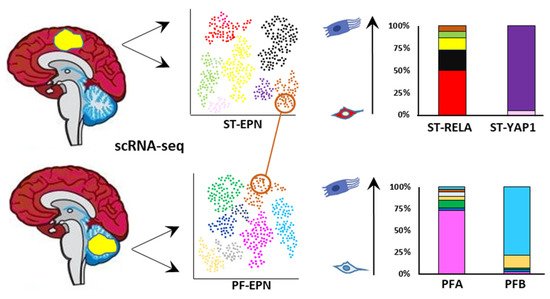

5. ITH of EPN: A Single-Cell Perspective

5.1. EPN Is Composed of Multiple Discrete Neoplastic Subpopulations

The four major childhood EPN subgroups dissected by scRNA-seq appear to be a composite mixture of multiple phenotypically discrete neoplastic subpopulations with divergent transcriptomic profiles. Although transcriptional signatures and their number differ across EPN subgroups, the common patterns of ITH that have been observed are mostly associated with cell cycle and neurodevelopmental programs. Contrasting the current classification paradigms, these studies have demonstrated that the relative proportions of the individual cell types dictate the molecular subgroup assignment, aggressiveness, and potential biomarkers of individual tumors, as reported in other brain tumors [102][191]. A high degree of ITH and enrichment for undifferentiated cell populations are associated with lower age and an unfavorable clinical outcome, as observed in ST-RELA and PFA, which might explain the profound difference in prognosis between these subtypes and their respective anatomical counterparts ST-YAP1 and PFB (Figure 45). Another commonality between ST-RELA and PFA is that cycling cells are specifically enriched in undifferentiated subpopulations, implying that progenitor subpopulations are more proliferative than more differentiated ones. Although, overall, cells separate according to the bulk tumor subgrouping, partially shared transcriptional programs are observed across all EPN molecular variants [103][104][164,165]. For instance, programs related to cell cycle, stress response, and ependymal differentiation are similar in ST-EPN and PF-EPN.

5.2. The Cell of Origin and Developmental Trajectories of EPN from an scRNA-seq Perspective

5.2. The Cell of Origin and Developmental Trajectories of EPN from an scRNA-seq Perspective

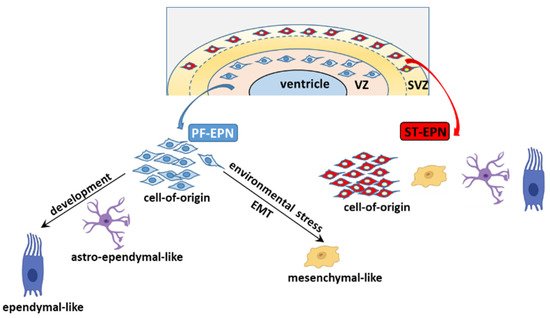

Leveraging scRNA-seq and TI analyses, it emerges that the distinct PF-EPN subpopulations are arranged in a neural tri-lineage cancer hierarchy driven by immature progenitor cells at the apex, that undergo impaired differentiation along neuronal, astrocytic, and ependymal-like trajectories [104][165]. Of the three branches, the predominant one sees the NSC-like population differentiate into less aggressive progenies, the astro-ependymal cells, and successively to ependymal-like cells, presumably in response to developmental or differentiation stimuli (Figure 56). This axis potentially overlaps with the differentiating trajectory described in Gillen et al.’s study, whereby the stem cell population of UEC-1 develops into TECs (which express markers of further differentiation, such as oRGC genes, as well as gliogenic progenitor and astrocytic progenitor genes), and then CECs characterized by an ependymal-like signature. In response to unfavorable microenvironmental cues, such as oxygen and/or nutrient deprivation in hypoxic areas, undifferentiated UEC-1 develop along a stress-associated trajectory and undergo EMT to give rise to mesenchymal MECs.

6. Therapeutic Applications

A potentially druggable pathway in PFA EPN is EZHIP, although direct targeting of EZHIP might prove difficult to achieve, because no enzymatic activity has hitherto been identified [105][207]. Numerous EZH2 inhibitors are currently undergoing phase 1 and phase 2 clinical testing in different tumors [106][210], and might have important implications for novel treatment protocols. Specifically, an advanced trial is evaluating the effectiveness of the EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat in pediatric patients with recurrent EPN (NCT03213665).

Compounds aimed at blocking the oncogenic NF-κB pathway [107][211] are potential therapeutic agents against ST-EPNs harboring ZFTA–RELA fusion that contains the NF-κB subunit encoding gene RELA. The NF-κB subunit is activated via proteosomal degradation of its inhibitor IκB, thus suggesting proteasome inhibitors as candidate drugs in ST-RELA [108][212]. scRNA-seq is expected to make significant breakthroughs in EPN and inform future therapeutic approaches. Since an increased proportion of differentiated cells is associated with a favorable clinical behavior in ST-RELA and PFA, differentiation-promoting agents might prove effective in these high-risk groups. Corroboratively, retinoids have demonstrated selective efficacy against EPN lines compared to other brain tumor-derived models in an in vitro drug screen [109][214]. In the context of PF-EPN, a druggable driver in the PF-NSC-like program is the Wnt pathway gene LGR5, a key mediator of cell proliferation and stemness features, as shown by small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated LGR5 knockdown that results in reduction of self-renewal [104][165]. In PF-Neuronal-Precursor-like cells, targetable pathways might be the epigenetic regulators HDAC2, DNMT3A, and BRD3. Indeed, the pan-HDAC inhibitor CN133 [110][215] and the HDAC2 inhibitor panobinostat [104][165], as well as the pan-BRD inhibitors JQ1 [111][199] and OTX012 [112][216], have been reported to decrease cell viability and tumor growth in patient-derived PFA cell lines. As for ST-EPN, actionable vulnerabilities in ST-Radial-Glia-like cells are FGFR3 and IGF2, whereas in the ST-Neuronal-Precursor-like subpopulation they are CCND2 and HDAC2. FGFR3 mRNA levels are enriched in ST-RELA EPNs, and specifically in cycling and progenitor-like cell populations, mirroring FGFR3 expression in RGCs of the embryonic and adult brain [113][218]. Indeed, blockade of FGFR by dominant-negative and pharmacological inhibitors impairs cell survival and stemness features in ST-RELA cells [104][113][165,218] Simultaneous inhibition of CDK4/6-CCND2 (with palbociclib) and IGF2/IGF1R (with ceritinib) pathways results in combinatorial drug efficacy, highlighting that targeting distinct subpopulations may be a successful therapeutic option [104][165]. CDK4/6 has also been proposed as an actionable driver in PFA, because the tumor suppressor gene CDKN2A, which codes for the CDK4/6 inhibitor p16, is epigenetically silenced by H3K27 trimethylation in PFA [114][105][146,207]. A phase 1 trial is addressing the safety and tolerability of the CDK4/6 inhibitor ribociclib in children and young adults with recurrent brain tumors, including EPN (NCT03434262). A link between the overexpression of strong growth-promoting IGF2 and members of the PLAG1/PLAG1L TF family is emerging in EPN. The PLAGL1 gene is developmentally regulated and is expressed in NSCs and developing neuroepithelial cells, with low expression in the adult brain [115][116][46,219]. Although the function of PLAGL1 in tumorigenesis is controversial, acting as either a tumor suppressor or an oncogene in a context-dependent manner, PLAG1L has been shown to foster progression of GBM [105][207]. In ST-RELA tumors, ZETA-RELA protein binds to PLAGL family TF motifs, indicating a possible corecruitment to drive ependymoma-related transcriptional programs [117][106]. PLAG1 is silenced during development by PRC2-mediated H3K27 trimethylation; however, in tumors with impaired PRC2 function, such as PFA and H3K27M mutant pHGG, PLAG1 is derepressed, leading to overexpression of its downstream targets, including IGF2 [105][207]. Therefore, it is conceivable to hypothesize that the PLAG1/PLAG1L-IGF2 axis might be therapeutically targeted in EPN.