Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hiroyuki Shimada | + 1742 word(s) | 1742 | 2022-01-10 10:23:24 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1742 | 2022-01-27 03:47:43 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1742 | 2022-01-29 01:23:27 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Shimada, H. Histopathology of the Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18862 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Shimada H. Histopathology of the Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18862. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Shimada, Hiroyuki. "Histopathology of the Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18862 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Shimada, H. (2022, January 26). Histopathology of the Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18862

Shimada, Hiroyuki. "Histopathology of the Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

The word “neuroblastoma” is often used as an omnibus term for all peripheral neuroblastic tumors (pNTs), including neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma and ganglioneuroma. As well defined by Willis, neuroblastoma is an embryonal tumor of neural crest origin. We believe that all ganglioneuromas were once neuroblastomas in their early stage of tumor development. Tumors in this group are known to present with a wide range of clinical behaviors, such as spontaneous regression, tumor maturation and aggressive progression refractory to intensive treatment. Because of the difficulty in predicting clinical outcomes of the patients, neuroblastoma was described as an enigmatic disease for many years.

neuroblastoma

International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification

Precision medicine

1. Introduction

The word “neuroblastoma” is often used as an omnibus term for all peripheral neuroblastic tumors (pNTs), including neuroblastoma, ganglioneuroblastoma and ganglioneuroma. As well defined by Willis [1], neuroblastoma is an embryonal tumor of neural crest origin. We believe that all ganglioneuromas were once neuroblastomas in their early stage of tumor development. Tumors in this group are known to present with a wide range of clinical behaviors, such as spontaneous regression, tumor maturation and aggressive progression refractory to intensive treatment. Because of the difficulty in predicting clinical outcomes of the patients, neuroblastoma was described as an enigmatic disease for many years.

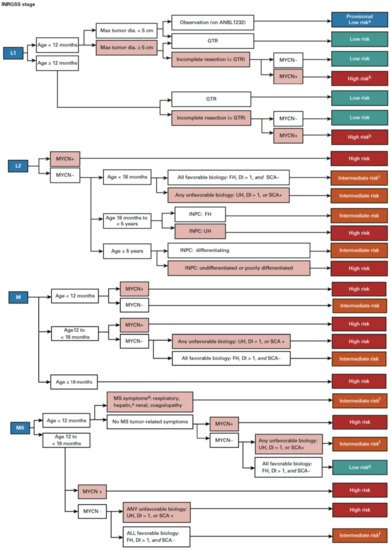

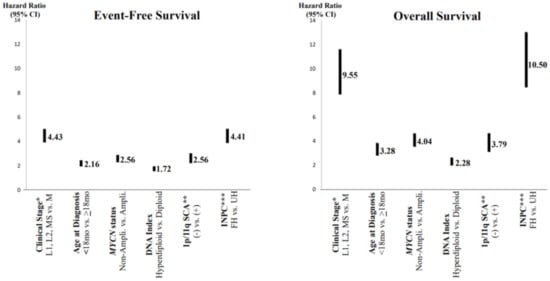

2. Prognostic Factors and Risk Classification

In order to predict a wide range of clinical behaviors of the patients with pNTs, there have been several risk grouping systems historically proposed by different cooperative groups, such as the International Society for Paediatric Oncology European Neuroblastoma (SIOPEN), the Gesellschaft für Paediatrische Onkologie und Haematologie (GPOH) and the Children’s Oncology Group (COG). Currently, two systems, the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) and the COG risk classification system, are widely accepted; both are based on a combination of so-called prognostic factors, such as clinical stage, patient age at diagnosis, histopathology, and genetic and genomic/molecular properties. The INRG has been designed to facilitate the comparison of risk-based clinical trials conducted in different regions and countries and distinguishes very low (>85% survival), low (75–85% survival), intermediate (50–75% survival) and high-risk (<50% survival) patients [2], while the COG risk classification system has been used for the purpose of patient stratification and protocol assignment in international clinical trials [3][4]. Prognostic factors utilized in the latest and revised COG system include clinical staging, according to the INRG Staging System (INRGSS; Stages L1, L2, M and MS); age at diagnosis (new cut-off points at 365 days, 548 days and 5 years); histopathology, according to the INPC (favorable histology (FH) vs. unfavorable histology (UH)); MYCN oncogene status (non-amplified vs. amplified); DNA index (hyperdiploid vs. diploid); and segmental chromosomal aberrations (1p−, 11q−, 17q+; No vs. Yes) [5]. The hazard ratio by each prognostic factor is shown in the Figure 1 and the recent and revised COG neuroblastoma risk classification system is summarized in Figure 2 [5]. Treatment of patients in the low-risk group is often followed by observation (with no chemotherapy or radiation) after surgery or even biopsy alone. Intermediate-risk patients are treated with surgery or biopsy, followed by non-aggressive chemotherapy. High-risk patients are treated with intensive chemotherapy, surgery, radiation therapy, bone marrow/hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and biological-based therapies. The reported 5-year survival rates for non-high-risk and high-risk patients are around 90% and 50%, respectively [5].

Figure 1. Neuroblastoma, prognostic factors and hazard ratios. * Clinical stage according to the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Staging System; ** SCA = segmental chromosomal aberrations; *** INPC = International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification (FH = favorable histology, UH = unfavorable histology). Note: Clinical stage (localized (L1 and L1) and MS (metastatic, special) disease vs. M (metastatic) disease) and INPC (FH group vs. UH group) distinguish tow prognostic groups with very high hazard ratio.

3. Histopathology of the Peripheral Neuroblastic Tumors

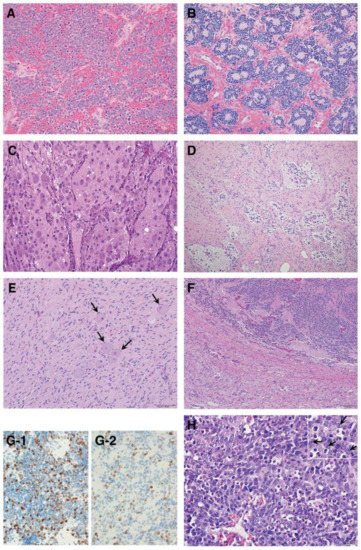

As summarized in Figure 3, according to the INPC, pNTs include four categories and the presence or absence of Schwannian stromal development is noted in parenthesis after the specific tumor category. They are Neuroblastoma (Schwannian stroma-poor); Ganglioneuroblastoma, Intermixed (Schwannian stroma-rich); Ganglioneuroma (Schwannian stroma-dominant); and Ganglioneuroblastoma, Nodular (composite, Schwannian stroma-rich/stroma-dominant and stroma-poor) [6]. The Neuroblastoma category contains three subtypes—undifferentiated, poorly differentiated and differentiating—based on the grade of neuroblastic differentiation. The Ganglioneuroma category contains two subtypes—maturing and mature. The INPC also includes three classes of mitosis–karyorrhexis index (MKI)—low (<100/5000 cells), intermediate (100–200/5000 cells) and high (>200/5000 cells)—as another morphologic indicator for tumors in the Neuroblastoma category. As summarized in Table 1, the INPC distinguishes two prognostic groups, the FH group and UH group, based on the age-dependent evaluation of histologic findings [7][8].

Figure 3. Histologic features of peripheral neuroblastic tumors: (A) neuroblastoma (Schwannian stroma-poor), undifferentiated subtype (original, ×200); (B) neuroblastoma (Schwannian stroma-poor), poorly differentiated subtype (original, ×200); (C) neuroblastoma (Schwannian stroma-poor), differentiating subtype (original, ×200); (D) ganglioneuroblastoma, intermixed (Schwannian stroma-rich) (original, ×100); (E) ganglioneuroma (Schwannian stroma-dominant)—note that completely mature ganglion cells are covered with satellite cells (arrows) (original, ×200); (F) ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular (composite, Schwannian stroma-rich/stroma-dominant and stroma-poor)—note two distinct histologies, i.e., neuroblastoma in the upper half and ganglioneuroma in the lower half in this case (original ×100); (G) Ki-67 immunostaining on two neuroblastomas of poorly differentiated subtype with a low mitosis–karyorrhexis index (original ×400). Note: (G-1) shows biopsy from rapidly enlarging liver of 3-month-old baby (Stage MS case, favorable histology) before starting spontaneous regression; (G-2) shows biopsy from abdominal mass of 5-year-old child (Stage M case, unfavorable histology). The favorable histology tumor contains numerous and more Ki-67 positive nuclei than the unfavorable histology tumor. (H) MYCN oncogene-amplified neuroblastoma demonstrating a characteristic histology of poorly differentiated subtype with a high mitosis–karyorrhexis index (original, ×400). Note: Tumor cells show nucleolar hypertrophy (Inset: prominent nucleoli indicated by arrows).

Table 1. International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification.

| Age at Diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroblastoma (Schwannian stroma-poor) | <548 days | 548 days–5 years | ≥5 years | ||

| Undifferentiated subtype | |||||

| With | Any MKI | ||||

| Poorly differentiated subtype | |||||

| With | Low MKI | ||||

| Intermediate MKI | |||||

| High MKI | |||||

| Differentiated subtype | |||||

| With | Low MKI | ||||

| Intermediate MKI | |||||

| High MKI | |||||

| Ganglioneuroblastoma, Intermixed |  |

||||

| (Schwannian stroma-rich) | |||||

| Ganglioneuroma | |||||

| (Schwannian stroma-dominant) | |||||

| Maturing subtype | |||||

| Mature subtype | |||||

| Ganglioneuroblastoma, Nodular |  |

||||

| (Composite, Schwannian stroma-rich/ | |||||

| stroma-dominant and stroma-poor) | |||||

Blue: Favorable Histology; Red: Unfavorable Histology; MKI = Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index.

3.1. Favorable Histology (FH) Tumors

Clinically favorable pNTs seem to show spontaneous regression or age-appropriate tumor differentiation/maturation. The best-known example of spontaneous regression is observed in stage 4S or MS disease whose tumor is classified into the FH group (typically Neuroblastoma, poorly differentiated subtype, with a low MKI diagnosed less than 365 days (stage 4S) or 548 days (stage MS)) [9][10]. In the stage 4S or MS disease, neuroblastoma cells characteristically become apoptotic and disappear without differentiation/maturation. While other FH tumors show differentiation/maturation within the age–appropriate framework, tumor differentiation/maturation is prompted by the “cross-talk” supported by critical signaling pathways, such as trkA/NGF signaling and Nrg1/ErbB signaling, between neuronal tumor cells and Schwannian stromal cells [11][12][13]. FH tumors with potential of differentiation/maturation in the Neuroblastoma category are poorly differentiated subtype (diagnosed up to 548 days of age at diagnosis) and differentiated subtype (diagnosed up to 5 years of age at diagnosis). All tumors in the Ganglioneuroblastoma, Intermixed and Ganglioneuroma categories (usually diagnosed in older children even over 5 years of age at diagnosis) are classified into the FH tumors. The prognostic effects by MKI are also age-dependent [14]; a low MKI less than 5 years of age and an intermediate MKI less than 365 days of age indicate favorable clinical outcome.

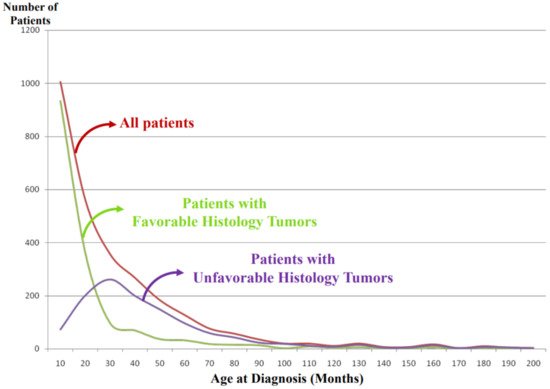

It is noted that vast majority of the FH tumors are clinically detected and diagnosed right after birth and during the first year of life (Figure 4). Some tumors are found perinatally by ultra-sound test. This could most likely be attributable to the growth rate/speed of the tumors in the FH group. In other words, FH tumors seem to grow rapidly in utero and/or during infancy and then stop growing or slow down the growth toward either spontaneous regression or tumor differentiation/maturation. For example, tumor causing giant hepatomegaly in stage 4S or MS disease is often composed of numerous Ki-67 positive neuroblasts (please see Figure 3G) before entering the phase of spontaneous regression. The numbers of Ki-67-positive cells of FH tumors in 4S/MS disease are more abundant than those of UH tumors in stage 4/M disease, suggesting the growth rate of the former tumors is more rapid than that of the latter tumors. It is also interesting to note that mass-screening systems for neuroblastoma, which started in Japan and preclinically detected neuroblastoma patients by checking urinary VMA/HVA levels at the age of 6 months [15], ended up collecting more than double newly diagnosed cases without significantly changing population-based mortality rates [16]. Those preclinically detected neuroblastomas were almost exclusively favorable, biologically and histopathologically [17][18]. In other words, during the perinatal/infantile period, there seems to be a huge number of spontaneously regressing FH neuroblastomas that would never reach the level of clinical detection.

Figure 4. International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification: patient distribution by age at diagnosis. Note: Most of the patients having favorable histology tumors are clinically detected and diagnosed in younger-age groups than the patients having unfavorable histology tumors.

3.2. Unfavorable Histology (UH) Tumors

The vast majority of high-risk cases is composed of tumors in the UH group. They do not seem to show a potential of age-appropriate differentiation/maturation. Among the Neuroblastoma category, UH tumors include the undifferentiated subtype (at any age), poorly differentiated subtype (over 548 days of age at diagnosis) and differentiating subtype (over 5 years of age at diagnosis). Adverse prognostic effects of the MKI are also age-dependent—high MKI at any age, intermediate MKI over 548 days and even low MKI over 5 years of age allocate the given tumors to the UH group, respectively [14]. It is reported that MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma characteristically presents with high MKI of either undifferentiated or poorly differentiated subtype in the Neuroblastoma category (please see Figure 3H) [14][19]. Tumors in the Ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular category are composed of distinct components representing different clones. One shows histologic appearance of either Ganglioneuroma or Ganglioneuroblastoma, intermixed and the other is Neuroblastoma characteristically forming a hemorrhagic nodule with or without necrosis. The prognostic distinction of Ganglioneuroblastoma, Nodular is based on the same age-linked evaluation of grade of neuroblastic differentiation (subtype) and MKI of Neuroblastoma nodule of each case. It is reported that 83% of the patients with Ganglioneuroblastoma, Nodular were over 548 days of age at diagnosis and 83% of their tumors were classified into the UH Group [20].

As shown in Figure 4, the tumors in the UH group are clinically detected and diagnosed in children who are older than those with the FH tumors. We speculate that UH tumors seem to grow rather slowly in the utero and during the first year of life compared with the FH tumors and that the UH tumors keep increasing their size with or without metastatic spread, finally becoming clinically detectable with a peak incidence around 2–3 years of age.

References

- Willis, R. Neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroma. In Pathology of Tumours; Appleton-Century-Crofts: New York, NY, USA, 1967.

- Cohn, S.L.; Pearson, A.D.; London, W.B.; Monclair, T.; Ambros, P.F.; Brodeur, G.M.; Faldum, A.; Hero, B.; Iehara, T.; Machin, D.; et al. The International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) classification system: An INRG Task Force report. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 289–297.

- Weinstein, J.L.; Katzenstein, H.M.; Cohn, S.L. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of neuroblastoma. Oncologist 2003, 8, 278–292.

- Park, J.R.; Bagatell, R.; London, W.B.; Maris, J.M.; Cohn, S.L.; Mattay, K.K.; Hogarty, M. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: Neuroblastoma. Pediatric Blood Cancer 2013, 60, 985–993.

- Irwin, M.S.; Naranjo, A.; Zhang, F.F.; Cohn, S.L.; London, W.B.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Ramirez, N.C.; Pfau, R.; Reshmi, S.; Wagner, E.; et al. Revised Neuroblastoma Risk Classification System: A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 3229–3241.

- Shimada, H.; Ambros, I.M.; Dehner, L.P.; Hata, J.; Joshi, V.V.; Roald, B. Terminology and morphologic criteria of neuroblastic tumors: Recommendations by the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Committee. Cancer 1999, 86, 349–363.

- Shimada, H.; Ambros, I.M.; Dehner, L.P.; Hata, J.; Joshi, V.V.; Roald, B.; Stram, D.O.; Gerbing, R.B.; Lukens, J.N.; Matthay, K.K.; et al. The International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification (the Shimada system). Cancer 1999, 86, 364–372.

- Peuchmaur, M.; d’Amore, E.S.; Joshi, V.V.; Hata, J.; Roald, B.; Dehner, L.P.; Gerbing, R.B.; Stram, D.O.; Lukens, J.N.; Matthay, K.K.; et al. Revision of the International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification: Confirmation of favorable and unfavorable prognostic subsets in ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular. Cancer 2003, 98, 2274–2281.

- Twist, C.J.; Naranjo, A.; Schmidt, M.L.; Tenney, S.C.; Cohn, S.L.; Meany, H.J.; Mattei, P.; Adkins, E.S.; Shimada, H.; London, W.B.; et al. Defining risk factors for chemotherapeutic intervention in infants with stage 4S neuroblastoma: A report from Children’s Oncology Group Study ANBL0531. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 115–124.

- Kawano, A.; Hazard, F.K.; Chiu, B.; Naranjo, A.; LaBarre, B.; London, W.B.; Hogarty, M.D.; Cohn, S.L.; Maris, J.M.; Park, J.R.; et al. Stage 4S Neuroblastoma: Molecular, Histologic, and Immunohistochemical Characteristics and Presence of 2 Distinct Patterns of MYCN Protein Overexpression—A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2021, 45, 1075–1081.

- Liu, S.; Tian, Y.; Chlenski, A.; Yang, Q.; Zage, P.; Salwen, H.R.; Crawford, S.E.; Cohn, S.L. Cross-talk between Schwann cells and neuroblasts influences the biology of neuroblastoma xenografts. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 891–900.

- Brodeur, G.M.; Minturn, J.E.; Ho, R.; Simpson, A.M.; Iyer, R.; Varela, C.R.; Light, J.E.; Kolla, V.; Evans, A.E. Trk receptor expression and inhibition in neuroblastomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3244–3250.

- Pajtler, K.W.; Mahlow, E.; Odersky, A.; Lindner, S.; Stephan, H.; Bendix, I.; Eggert, A.; Schramm, A.; Schulte, J.H. Neuroblastoma in dialog with its stroma: NTRK1 is a regulator of cellular cross-talk with Schwann cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 11180–11192.

- Teshiba, R.; Kawano, S.; Wang, L.L.; He, L.; Naranjo, A.; London, W.B.; Seeger, R.C.; Gastier-Foster, J.M.; Look, A.T.; Hogarty, M.D.; et al. Age-dependent prognostic effect by Mitosis-Karyorrhexis Index in neuroblastoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatric Dev. Pathol. 2014, 17, 441–449.

- Sawada, T.; Kidowaki, T.; Sakamoto, I.; Hashida, T.; Matsumura, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Kusunoki, T. Neuroblastoma. Mass screening for early detection and its prognosis. Cancer 1984, 53, 2731–2735.

- Woods, W.G. Screening for neuroblastoma: The final chapters. J. Pediatric Hematol. Oncol. 2003, 25, 3–4.

- Brodeur, G.M.; Look, A.T.; Shimada, H.; Hamilton, V.M.; Maris, J.M.; Hann, H.W.; Leclerc, J.M.; Bernstein, M.; Brisson, L.C.; Brossard, J.; et al. Biological aspects of neuroblastomas identified by mass screening in quebec. Med. Pediatric Oncol. 2001, 36, 157–159.

- Kawakami, T.; Monobe, Y.; Monforte, H.; Woods, W.G.; Tuchman, M.; Lemieux, B.; Brisson, L.; Bernstein, M.; Brossard, J.; Leclerc, J.M.; et al. Pathology review of screening negative neuroblastomas. Cancer 1998, 83, 575–581.

- Shimada, H.; Stram, D.O.; Chatten, J.; Joshi, V.V.; Hachitanda, Y.; Brodeur, G.M.; Lukens, J.N.; Matthay, K.K.; Seeger, R.C. Identification of subsets of neuroblastomas by combined histopathologic and N-myc analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1995, 87, 1470–1476.

- Angelini, P.; London, W.B.; Cohn, S.L.; Pearson, A.D.J.; Matthay, K.K.; Monclair, T.; Ambros, P.F.; Shimada, H.; Leuschner, I.; Peuchmaur, M.; et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with ganglioneuroblastoma, nodular subtype: A report from the INRG project. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 1185–1191.

More

Information

Subjects:

Medicine, Research & Experimental

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No