| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dan Cristian Vodnar | + 5152 word(s) | 5152 | 2022-01-25 04:58:15 |

Video Upload Options

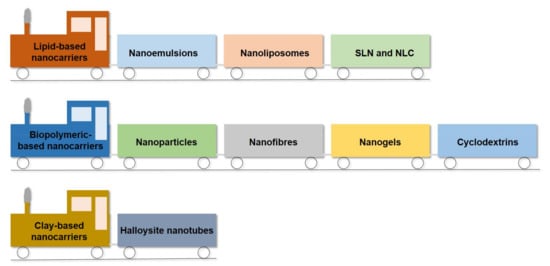

Lockdown has been installed due to the fast spread of COVID-19, and several challenges have occurred. Active packaging was considered a sustainable option for mitigating risks to food systems during COVID-19. Biopolymeric-based active packaging incorporating the release of active compounds with antimicrobial and antioxidant activity represents an innovative solution for increasing shelf life and maintaining food quality during transportation from producers to consumers. However, food packaging requires certain physical, chemical, and mechanical performances, which biopolymers such as proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids have not satisfied. In addition, active compounds have low stability and can easily burst when added directly into biopolymeric materials. Due to these drawbacks, encapsulation into lipid-based, polymeric-based, and nanoclay-based nanocarriers has currently captured increased interest. Nanocarriers can protect and control the release of active compounds and can enhance the performance of biopolymeric matrices.

1. Introduction

2. Nanocarriers for Sustainable Active Packaging

2.1. Lipid-Based Nanocarriers

2.1.1. Nanoemulsions

| Nanocarrier | Core Material | Wall Material | Active Packaging Matrix | Effects on Packaging Matrix | Effects on Food | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nano- emulsion |

Copaiba oil | - | Pectin film | Increased roughness with oil concentration, gradual reduction in elastic modulus and tensile strength, increased elongation at break, and antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and E. coli | - | [25] |

| Cinnamon EO | - | Pullulan film | Improved physicochemical properties and antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli | - | [26] | |

| Pickering nanoemulsion | Cinnamon-perilla EO | Collagen | Anthocyanidin/chitosan nano-composite film | Improved physical properties of films (e.g., mechanical, water vapor permeability and thermal stability), hydrophobicity, and antioxidant activity | Extended storage time by 6–8 d of fish fillets | [27] |

| Marjoran EO | Whey protein isolate, inulin | Pectin film | Exhibited good mechanical and water barrier properties Pickering emulsion had a slow release of EO and a lower antioxidant activity than nanoemulsion |

- | [28] | |

| Nano- liposomes |

Saffron extract components | Rapeseed lecithin | Pullulan film | Enhanced oxygen barrier | Additional benefits due to unique flavor and color of saffron | [29] |

| Betanin | - | Gelatin/chitosan nanofibers/ZnO NPs nanocomposite film |

Satisfactory mechanical properties and high surface hydrophobicity | High antimicrobial and antioxidant activity; controlled the growth of inoculated bacteria, lipid oxidation, and changes in the pH and color quality of beef meat | [30] | |

| Garlic EO | Phospholipid and cholesterol | Chitosan film | Improved mechanical properties and water resistance | Extended the shelf life of chicken fillet | [31] | |

| SLN | ꭤ-Tocopherol | Soya lecithin, Compritol®® 888 CG ATO | PVA film | Decreased crystallinity and increased antioxidant capacity | - | [22][32] |

| NLC | - | - | Calcium/alginate film | Decreased tensile strength, elastic modulus, swelling ratio; increased thermal stability, water vapor permeability, and contact angle by increasing NLC concentration; improved UV-absorbing properties | - | [33] |

2.1.2. Nanoliposomes

2.1.3. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nano-structured Lipid Carriers

2.2. Biopolymeric-Based Nanocarriers

2.2.1. Nanoparticles

| Nanocarrier | Core Material | Wall Material | Active Packaging Matrix | Effects on Packaging Matrix | Effects on Food | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nano- particles |

ZnO loaded Gallic acid | - | Chitosan film | Remarkably improved mechanical and physical properties | - | [23] |

| ZnO-loaded clove EO | Chitosan | Chitosan/ pullulan nano-composite film |

Enhanced tensile strength, film hydrophobicity, water vapor and oxygen barrier, and UV light blocking ability | Extend shelf life of chicken meat by up 5 d at 8 ± 2 °C | [43] | |

| ZnO | - | Chitosan/ bamboo leaves film |

High UV barrier and strong antioxidant and antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus | - | [44] | |

| TiO2 | - | Chitosan/ red apple pomace film |

Considerable mechanical properties | Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity, indicator for the freshness of salmon fillets | [45] | |

| TiO2 | - | Cellulose nanofiber/whey protein film | - | Increased shelf life of lamb meat from around 6 to 15 d | [46] | |

| Nanofibers | Mentha spicata L. EO and MgO NPs | Sodium caseinate/ gelatin |

- | - | Improved sensory attributes and increased shelf life of fresh trout fillets up to 13 d | [47] |

| Cinnam- aldehyde |

Pullulan/ ethyl cellulose |

- | Improved hydrophobicity and flexibility; inhibited E coli and S. aureus growth | - | [48] | |

| 1,8-cineole from spice EO | Zein | - | The higher the storage time, the higher the inhibitory effects against L. monocytogenes and S. aureus | Inhibited the growth of mesophilic bacteria counts in cheese slices | [49] | |

| Nanogels | Rosemary EO | Chitosan/ benzoic acid |

Starch/ carboxy- methyl cellulose film |

Improved tensile strength and transparency, increased water vapor permeability, and inhibited S. aureus | - | [50] |

| Clove EO | Chitosan/ myristic acid |

- | - | Increased antioxidant and antimicrobial activity against S. enteritica in beef meat | [51] | |

| Rosemary EO | Chitosan/ benzoic acid |

- | - | Inhibited microbial growth of S. typhimurium, preserved color values during storage, and increased the shelf life of beef meat | [52] | |

| Cyclodextrins | Cinnam- aldehyde |

- | High amylose corn starch/konjac glucomannan composite film | Decreased crystallinity; improved compatibility between the two polysaccharides and enhanced film physico-mechanical properties and thermal ability; inhibited S. aureus and E. coli growth | - | [53] |

| Satureja montana L. EO | - | Soy soluble polysaccharide hydrogel | More compact structure; improved hardness, adhesiveness, and springiness of hydrogel | Reduces the visible count of S. aureus in meat; retained freshness and extended the shelf life of chilled pork | [54] | |

| Carvacrol | - | Pectin coating | Nanocarriers improved aqueous solubility and thermal stability of carvacrol and showed strong antifungal activity against B. cinerea and A. alternata. In pectin films, nanocarriers decreased viscosity and increased thermal stability; inhibited above pathogens in vitro | - | [55] | |

| Halloysite nanotubes | Tea polyphenol |

- | Chitosan film | Improved water vapor permeability; had antioxidant and certain antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus growth; 3D printing properties | - | [56] |

| Salicylic acid | - | Alginate and pectin film | Cumulative release and antimicrobial activity were higher for alginate films | - | [57] | |

| Silver ions | APTMS | Carrageenan film | Silver ions-loaded APTMS modified halloysite nanotubes exhibited increased water contact angle, water vapor permeability, UV-light barrier, and antibacterial activity | - | [58] |

2.2.2. Nanofibers

2.2.3. Nanogels

2.2.4. Cyclodextrin-Based Inclusion Complex

2.3. Halloysite Nanotubes

References

- Vodnar, D.C.; Mitrea, L.; Teleky, B.E.; Szabo, K.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Nemeş, S.A.; Martău, G.A. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Caused by (SARS-CoV-2) Infections: A Real Challenge for Human Gut Microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 786.

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. WHO Director-General Speeches No. 4 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 24 November 2021).

- Kumar, P.; Singh, R.K. Strategic framework for developing resilience in Agri-Food Supply Chains during COVID 19 pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2021, 1–24.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Mitigating Risks to Food Systems during COVID-19: Reducing Food Loss and Waste. 2020. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca9056en/ca9056en.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2021).

- Galanakis, C.M.; Rizou, M.; Aldawoud, T.M.S.; Ucak, I.; Rowan, N.J. Innovations and technology disruptions in the food sector within the COVID-19 pandemic and post-lockdown era. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 193–200.

- De Sousa, F.D.B. Pros and Cons of Plastic during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Recycling 2020, 5, 27.

- Li, Q.; Ren, T.; Perkins, P.; Hu, X.; Wang, X. Applications of halloysite nanotubes in food packaging for improving film performance and food preservation. Food Control 2021, 124, 107876.

- Regulation (EC) No 1932/2004 on Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food and Repealing Directives 80/590/EEC and 89/109/EEC. 2004. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex%3A32004R1935 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Commision Regulation (EC) No 450/2009 on Active and Intelligent Materials and Articles Intended to Come into Contact with Food. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32009R0450 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Szabo, K.; Teleky, B.E.; Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.F.; Martău, G.A.; Simon, E.; Varvara, R.A.; Vodnar, D.C. Active Packaging—poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Films Enriched with Tomato By-Products Extract. Coatings 2020, 10, 141.

- Mitrea, L.; Călinoiu, L.-F.F.; Martău, G.-A.; Szabo, K.; Teleky, B.-E.E.; Mureșan, V.; Rusu, A.-V.V.; Socol, C.-T.T.; Vodnar, D.-C.C.; Mărtau, G.A. Poly(vinyl alcohol)-Based Biofilms Plasticized with Polyols and Colored with Pigments Extracted from Tomato By-Products. Polymers 2020, 12, 532.

- Kuai, L.; Liu, F.; Chiou, B.-S.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; McHugh, T.H.; Zhong, F. Controlled release of antioxidants from active food packaging: A Review. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106992.

- Rehman, A.; Jafari, S.M.; Aadil, R.M.; Assadpour, E.; Randhawa, M.A.; Mahmood, S. Development of active food packaging via incorporation of biopolymeric nanocarriers containing essential oils. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 101, 106–121.

- VBertolino, V.; Cavallaro, G.; Milioto, S.; Lazzara, G. Polysaccharides/Halloysite nanotubes for smart bionanocomposite materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 245, 116502.

- Nikolic, M.V.; Vasiljevic, Z.Z.; Auger, S.; Vidic, J. Metal oxide nanoparticles for safe active and intelligent food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 655–668.

- Wu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Cai, F.; Lu, P. ZnO nanoparticles stabilized oregano essential oil Pickering emulsion for functional cellulose nanofibrils packaging films with antimicrobial and antioxidant activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 190, 433–440.

- Jafari, S.M. Nanoencapsulation Technologies for the Food and Nutraceutical Industries; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 1–34.

- Chaudhari, A.K.; Singh, V.K.; Das, S.; Dubey, N.K. Nanoencapsulation of essential oils and their bioactive constituents: A novel strategy to control mycotoxin contamination in food system. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 149, 112019.

- ARezaei, A.; Fathi, M.; Jafari, S.M. Nanoencapsulation of hydrophobic and low-soluble food bioactive compounds within different nanocarriers. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 88, 146–162.

- Firouz, M.S.; Mohi-Alden, K.; Omid, M. A critical review on intelligent and active packaging in the food industry: Research and development. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110113.

- Zhang, L.; Yu, D.; Regenstein, J.M.; Xia, W.; Dong, J. A comprehensive review on natural bioactive films with controlled release characteristics and their applications in foods and pharmaceuticals. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 690–707.

- De Carvalho, S.M.; Noronha, C.M.; da Rosa, C.G.; Sganzerla, W.G.; Bellettini, I.C.; Nunes, M.R.; Bertoldi, F.C.; Manique Barreto, P.L. PVA antioxidant nanocomposite films functionalized with alpha-tocopherol loaded solid lipid nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 581, 123793.

- Yadav, S.; Mehrotra, G.; Dutta, P. Chitosan based ZnO nanoparticles loaded gallic-acid films for active food packaging. Food Chem. 2020, 334, 127605.

- Almasi, H.; Azizi, S.; Amjadi, S. Development and characterization of pectin films activated by nanoemulsion and Pickering emulsion stabilized marjoram (Origanum majorana L.) essential oil. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 99, 105338.

- Norcino, L.; Mendes, J.; Natarelli, C.; Manrich, A.; Oliveira, J.; Mattoso, L. Pectin films loaded with copaiba oil nanoemulsions for potential use as bio-based active packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 106, 105862.

- Chu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Feng, X.; Gao, C.; Wu, D.; Meng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. Fabrication, structure and properties of pullulan-based active films incorporated with ultrasound-assisted cinnamon essential oil nanoemulsions. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 25, 100547.

- Zhao, R.; Guan, W.; Zhou, X.; Lao, M.; Cai, L. The physiochemical and preservation properties of anthocyanidin/chitosan nanocomposite-based edible films containing cinnamon-perilla essential oil pickering nanoemulsions. LWT 2022, 153, 112506.

- Mohamed, H.M.; Mansour, H.A. Incorporating essential oils of marjoram and rosemary in the formulation of beef patties manufactured with mechanically deboned poultry meat to improve the lipid stability and sensory attributes. LWT 2012, 45, 79–87.

- Najafi, Z.; Kahn, C.J.; Bildik, F.; Arab-Tehrany, E.; Şahin-Yeşilçubuk, N. Pullulan films loading saffron extract encapsulated in nanoliposomes; preparation and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 62–71.

- Amjadi, S.; Nazari, M.; Alizadeh, S.A.; Hamishehkar, H. Multifunctional betanin nanoliposomes-incorporated gelatin/chitosan nanofiber/ZnO nanoparticles nanocomposite film for fresh beef preservation. Meat Sci. 2020, 167, 108161.

- Kamkar, A.; Molaee-aghaee, E.; Khanjari, A.; Akhondzadeh-basti, A.; Noudoost, B.; Shariatifar, N.; Alizadeh Sani, M.; Soleimani, M. Nanocomposite active packaging based on chitosan biopolymer loaded with nano-liposomal essential oil: Its characterizations and effects on microbial, and chemical properties of refrigerated chicken breast fillet. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 342, 109071.

- De Carvalho, S.M.; Noronha, C.M.; Floriani, C.L.; Lino, R.C.; Rocha, G.; Bellettini, I.C.; Ogliari, P.J.; Barreto, P.L.M. Optimization of α-tocopherol loaded solid lipid nanoparticles by central composite design. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 49, 278–285.

- Khorrami, N.K.; Radi, M.; Amiri, S.; McClements, D.J. Fabrication and characterization of alginate-based films functionalized with nanostructured lipid carriers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 373–384.

- Martău, G.A.; Teleky, B.-E.; Ranga, F.; Pop, I.D.; Vodnar, D.C. Apple pomace as a sustainable substrate in sourdough fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 1–16.

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Cimpeanu, C.; Turcuş, V.; Predoi, G.; Iordache, F. Nanoencapsulation techniques for compounds and products with antioxidant and antimicrobial activity—A critical view. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 157, 1326–1345.

- Wang, P.; Wu, Y. A review on colloidal delivery vehicles using carvacrol as a model bioactive compound. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106922.

- Gupta, S.; Variyar, P.S. Nanoencapsulation of Essential Oils for Sustained Release: Application as Therapeutics and Antimicrobials; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- Katopodi, A.; Detsi, A. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers of natural products as promising systems for their bioactivity enhancement: The case of essential oils and flavonoids. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 630, 127529.

- Araujo, V.H.S.; Delello Di Filippo, L.; Duarte, J.L.; Spósito, L.; de Camargo, B.A.F.; da Silva, P.B.; Chorilli, M. Exploiting solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers for drug delivery against cutaneous fungal infections. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 47, 79–90.

- Xue, J.; Wang, T.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, M.; Luo, Y. A novel and organic solvent-free preparation of solid lipid nanoparticles using natural biopolymers as emulsifier and stabilizer. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 531, 59–66.

- Assadpour, E.; Jafari, S.M. Nanoencapsulation. In Nanomaterials for Food Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 35–61.

- Ghosh, T.; Mahansaria, R.; Katiyar, V. Nanoencapsulation: Prospects in Edible Food Packaging. In Nanotechnology in Edible Food Packaging; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 259–272.

- Gasti, T.; Dixit, S.; Hiremani, V.D.; Chougale, R.B.; Masti, S.P.; Vootla, S.K.; Mudigoudra, B.S. Chitosan/pullulan based films incorporated with clove essential oil loaded chitosan-ZnO hybrid nanoparticles for active food packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 277, 118866.

- Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, G.; Hu, L.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y. Chitosan-based films with antioxidant of bamboo leaves and ZnO nanoparticles for application in active food packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 363–369.

- Lan, W.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J. Development of red apple pomace extract/chitosan-based films reinforced by TiO2 nanoparticles as a multifunctional packaging material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 168, 105–115.

- Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Mohammadian, E.; McClements, D.J. Eco-friendly active packaging consisting of nanostructured biopolymer matrix reinforced with TiO2 and essential oil: Application for preservation of refrigerated meat. Food Chem. 2020, 322, 126782.

- Eghbalian, M.; Shavisi, N.; Shahbazi, Y.; Dabirian, F. Active packaging based on sodium caseinate-gelatin nanofiber mats encapsulated with Mentha spicata L. essential oil and MgO nanoparticles: Preparation, properties, and food application. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100737.

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Q.; Kong, B.; Wang, H. Fabrication and characterization of cinnamaldehyde loaded polysaccharide composite nanofiber film as potential antimicrobial packaging material. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 26, 100600.

- Göksen, G.; Fabra, M.J.; Ekiz, H.I.; López-Rubio, A. Phytochemical-loaded electrospun nanofibers as novel active edible films: Characterization and antibacterial efficiency in cheese slices. Food Control. 2020, 112, 107133.

- Mohsenabadi, N.; Rajaei, A.; Tabatabaei, M.; Mohsenifar, A. Physical and antimicrobial properties of starch-carboxy methyl cellulose film containing rosemary essential oils encapsulated in chitosan nanogel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 148–155.

- Rajaei, A.; Hadian, M.; Mohsenifar, A.; Rahmani-Cherati, T.; Tabatabaei, M. A coating based on clove essential oils encapsulated by chitosan-myristic acid nanogel efficiently enhanced the shelf-life of beef cutlets. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2017, 14, 137–145.

- Hadian, M.; Rajaei, A.; Mohsenifar, A.; Tabatabaei, M. Encapsulation of Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils in chitosan-benzoic acid nanogel with enhanced antibacterial activity in beef cutlet against Salmonella typhimurium during refrigerated storage. LWT 2017, 84, 394–401.

- Zou, Y.; Yuan, C.; Cui, B.; Wang, J.; Yu, B.; Guo, L.; Dong, D. Mechanical and antimicrobial properties of high amylose corn starch/konjac glucomannan composite film enhanced by cinnamaldehyde/β-cyclodextrin complex. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 170, 113781.

- Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Lin, L. Antibacterial efficacy of Satureja montana L. essential oil encapsulated in methyl-β-cyclodextrin/soy soluble polysaccharide hydrogel and its assessment as meat preservative. LWT 2021, 152, 112427.

- Sun, C.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Sun, C. Preparation and characterization of pectin-based edible coating agent encapsulating carvacrol/HPβCD inclusion complex for inhibiting fungi. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 125, 107374.

- Wang, Y.; Yi, S.; Lu, R.; Sameen, D.E.; Ahmed, S.; Dai, J.; Qin, W.; Li, S.; Liu, Y. Preparation, characterization, and 3D printing verification of chitosan/halloysite nanotubes/tea polyphenol nanocomposite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 166, 32–44.

- Kurczewska, J.; Ratajczak, M.; Gajecka, M. Alginate and pectin films covering halloysite with encapsulated salicylic acid as food packaging components. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 214, 106270.

- Saedi, S.; Shokri, M.; Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Silver loaded aminosilane modified halloysite for the preparation of carrageenan-based functional films. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 211, 106170.

- Coelho, S.C.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Encapsulation in food industry with emerging electrohydrodynamic techniques: Electrospinning and electrospraying—A review. Food Chem. 2020, 339, 127850.

- Sameen, D.E.; Ahmed, S.; Lu, R.; Li, R.; Dai, J.; Qin, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Liu, Y. Electrospun nanofibers food packaging: Trends and applications in food systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 16, 1–14.

- Zhang, Z.; Hao, G.; Liu, C.; Fu, J.; Hu, D.; Rong, J.; Yang, X. Recent progress in the preparation, chemical interactions and applications of biocompatible polysaccharide-protein nanogel carriers. Food Res. Int. 2021, 147, 110564.

- Keskin, D.; Zu, G.; Forson, A.M.; Tromp, L.; Sjollema, J.; van Rijn, P. Nanogels: A novel approach in antimicrobial delivery systems and antimicrobial coatings. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 3634–3657.

- Shah, S.; Rangaraj, N.; Laxmikeshav, K.; Sampathi, S. Nanogels as drug carriers–Introduction, chemical aspects, release mechanisms and potential applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 581, 119268.

- Coman, V.; Oprea, I.; Leopold, L.F.; Vodnar, D.C.; Coman, C. Soybean Interaction with Engineered Nanomaterials: A Literature Review of Recent Data. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1248.

- Maqsoudlou, A.; Assadpour, E.; Mohebodini, H.; Jafari, S.M. Improving the efficiency of natural antioxidant compounds via different nanocarriers. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 278, 102122.

- Liu, Z.; Ye, L.; Xi, J.; Wang, J.; Feng, Z.-G. Cyclodextrin Polymers: Structure, Synthesis, and Use as Drug Carriers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 118, 101408.

- Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Ke, Q.; Kou, X. Cyclodextrins as carriers for volatile aroma compounds: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 269, 118292.

- Liu, Y.; Sameen, D.E.; Ahmed, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, R.; Dai, J.; Li, S.; Qin, W. Recent advances in cyclodextrin-based films for food packaging. Food Chem. 2022, 370, 131026.

- Plamada, D.; Vodnar, D.C. Polyphenols—Gut Microbiota Interrelationship: A Transition to a New Generation of Prebiotics. Nutrients 2022, 14, 137.

- Martău, G.A.; Mihai, M.; Vodnar, D.C. The Use of Chitosan, Alginate, and Pectin in the Biomedical and Food Sector—Biocompatibility, Bioadhesiveness, and Biodegradability. Polymers 2019, 11, 1837.