| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Igor Erjavec | + 2598 word(s) | 2598 | 2022-01-12 09:44:06 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 74 word(s) | 2672 | 2022-01-23 07:57:25 | | |

Video Upload Options

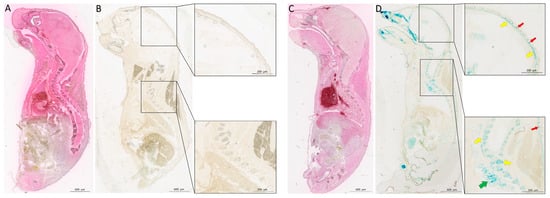

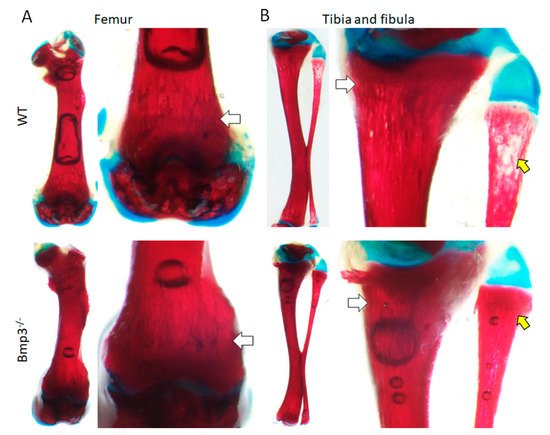

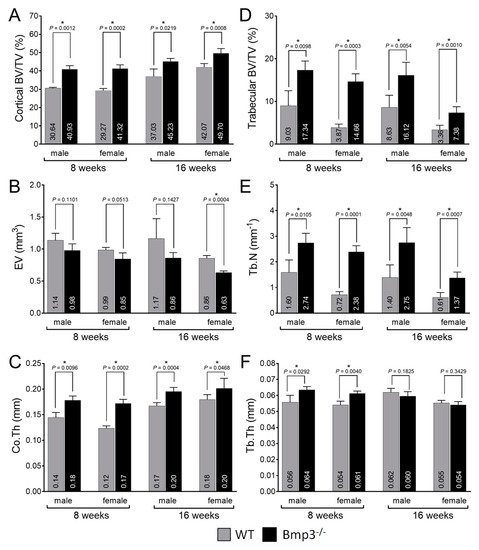

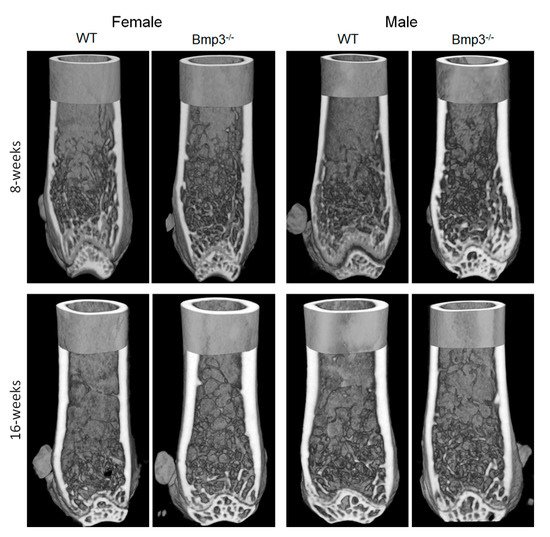

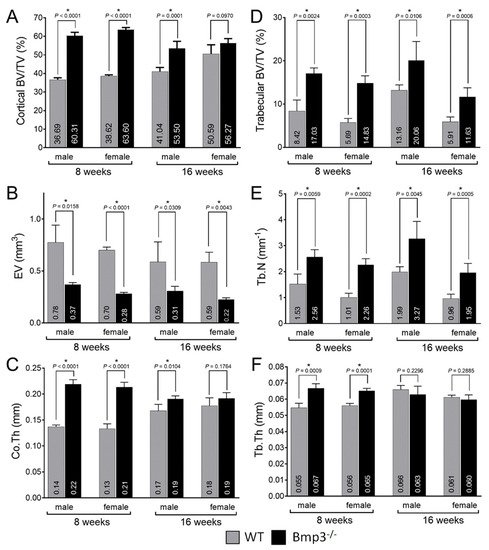

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) have a major role in tissue development. BMP3 is synthesized in osteocytes and mature osteoblasts and has an antagonistic effect on other BMPs in bone tissue. The main aim of this study was to fully characterize cortical bone and trabecular bone of long bones in both male and female Bmp3−/− mice. To investigate the effect of Bmp3 from birth to maturity, we compared Bmp3−/− mice with wild-type littermates at the following stages of postnatal development: 1 day (P0), 2 weeks (P14), 8 weeks and 16 weeks of age. Bmp3 deletion was confirmed using X-gal staining in P0 animals. Cartilage and bone tissue were examined in P14 animals using Alcian Blue/Alizarin Red staining. Detailed long bone analysis was performed in 8-week-old and 16-week-old animals using micro-CT. The Bmp3 reporter signal was localized in bone tissue, hair follicles, and lungs. Bone mineralization at 2 weeks of age was increased in long bones of Bmp3−/− mice. Bmp3 deletion was shown to affect the skeleton until adulthood, where increased cortical and trabecular bone parameters were found in young and adult mice of both sexes, while delayed mineralization of the epiphyseal growth plate was found in adult Bmp3−/− mice.

1. Introduction

2. Current Insights

3. Conclusions

References

- Vukicevic, S.; Sampath, K.T. (Eds.) Bone Morphogenetic Proteins: From Laboratory to Clinical Practice; Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland, 2002; ISBN 3-7643-6509-9.

- Chen, D.; Zhao, M.; Mundy, G.R. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 2004, 22, 233–241.

- Katagiri, T.; Watabe, T. Bone Morphogenetic Proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a021899.

- Wozney, J.M. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Prog. Growth Factor Res. 1989, 1, 267–280.

- Wozney, J.M.; Rosen, V. Bone morphogenetic protein and bone morphogenetic protein gene family in bone formation and repair. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1998, 346, 26–37.

- Vukicevic, S.; Luyten, F.P.; Reddi, A.H. Stimulation of the expression of osteogenic and chondrogenic phenotypes in vitro by osteogenin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 8793–8797.

- Luyten, F.P.; Cunningham, N.S.; Vukicevic, S.; Paralkar, V.; Ripamonti, U.; Reddi, A.H. Advances in osteogenin and related bone morphogenetic proteins in bone induction and repair. Acta Orthop. Belg. 1992, 58 (Suppl. 1), 263–267.

- Luyten, F.P.; Yu, Y.M.; Yanagishita, M.; Vukicevic, S.; Hammonds, R.G.; Reddi, A.H. Natural bovine osteogenin and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2B are equipotent in the maintenance of proteoglycans in bovine articular cartilage explant cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 3691–3695.

- Vukicevic, S.; Paralkar, V.M.; Cunningham, N.S.; Gutkind, J.S.; Reddi, A.H. Autoradiographic localization of osteogenin binding sites in cartilage and bone during rat embryonic development. Dev. Biol. 1990, 140, 209–214.

- Bahamonde, M.E.; Lyons, K.M. BMP3: To be or not to be a BMP. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2001, 83 (Suppl. 1), S56–S62.

- Bialek, P.; Parkington, J.; Li, X.; Gavin, D.; Wallace, C.; Zhang, J.; Root, A.; Yan, G.; Warner, L.; Seeherman, H.J.; et al. A myostatin and activin decoy receptor enhances bone formation in mice. Bone 2014, 60, 162–171.

- Daluiski, A.; Engstrand, T.; Bahamonde, M.E.; Gamer, L.W.; Agius, E.; Stevenson, S.L.; Cox, K.; Rosen, V.; Lyons, K.M. Bone morphogenetic protein-3 is a negative regulator of bone density. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 84–88.

- Zoricic, S.; Maric, I.; Bobinac, D.; Vukicevic, S. Expression of bone morphogenetic proteins and cartilage-derived morphogenetic proteins during osteophyte formation in humans. J. Anat. 2003, 202, 269–277.

- Kokabu, S.; Gamer, L.; Cox, K.; Lowery, J.; Tsuji, K.; Raz, R.; Economides, A.; Katagiri, T.; Rosen, V. BMP3 suppresses osteoblast differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells via interaction with Acvr2b. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 87–94.

- Yamashita, K.; Mikawa, S.; Sato, K. BMP3 expression in the adult rat CNS. Brain Res. 2016, 1643, 35–50.

- Ciller, I.M.; Palanisamy, S.K.; Ciller, U.A.; McFarlane, J.R. Postnatal expression of bone morphogenetic proteins and their receptors in the mouse testis. Physiol. Res. 2016, 65, 673–682.

- Vukicevic, S.; Helder, M.N.; Luyten, F.P. Developing human lung and kidney are major sites for synthesis of bone morphogenetic protein-3 (osteogenin). J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1994, 42, 869–875.

- Zhou, X.; Tao, Y.; Liang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Q. BMP3 Alone and Together with TGF-β Promote the Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells into a Nucleus Pulposus-Like Phenotype. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 20344–20359.

- Cernea, M.; Tang, W.; Guan, H.; Yang, K. Wisp1 mediates Bmp3-stimulated mesenchymal stem cell proliferation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2016, 56, 39–46.

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, W.; Cao, Y.; Shi, Y.; Lei, C.; Du, B.; Li, X.; Zhang, Q. The Functions of BMP3 in Rabbit Articular Cartilage Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 25934–25946.

- Gamer, L.W.; Ho, V.; Cox, K.; Rosen, V. Expression and function of BMP3 during chick limb development. Dev. Dyn. 2008, 237, 1691–1698.

- Gamer, L.W.; Cox, K.; Carlo, J.M.; Rosen, V. Overexpression of BMP3 in the developing skeleton alters endochondral bone formation resulting in spontaneous rib fractures. Dev. Dyn. 2009, 238, 2374–2381.

- Liu, J.; Hu, Y.; Ma, Z. The experimental study on expression of BMP3 gene during fracture healing. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi 1996, 34, 585–588.

- Zheng, L.; Yamashiro, T.; Fukunaga, T.; Balam, T.A.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Bone morphogenetic protein 3 expression pattern in rat condylar cartilage, femoral cartilage and mandibular fracture callus. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2005, 113, 318–325.

- Kloen, P.; Lauzier, D.; Hamdy, R.C. Co-expression of BMPs and BMP-inhibitors in human fractures and non-unions. Bone 2012, 51, 59–68.

- Matzelle, M.M.; Shaw, A.T.; Baum, R.; Maeda, Y.; Li, J.; Karmakar, S.; Manning, C.A.; Walsh, N.C.; Rosen, V.; Gravallese, E.M. Inflammation in arthritis induces expression of BMP3, an inhibitor of bone formation. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 45, 379–383.

- Fan, L.; Fan, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; Deng, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, R.C. miR-450b Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation In Vitro and Enhances Bone Formation In Vivo by Targeting BMP3. Stem Cells Dev. 2018, 27, 600–611.

- Aspenberg, P.; Basic, N.; Tägil, M.; Vukicevic, S. Reduced expression of BMP-3 due to mechanical loading: A link between mechanical stimuli and tissue differentiation. Acta Orthop. Scand. 2000, 71, 558–562.

- Dai, Z.; Popkie, A.P.; Zhu, W.-G.; Timmers, C.D.; Raval, A.; Tannehill-Gregg, S.; Morrison, C.D.; Auer, H.; Kratzke, R.A.; Niehans, G.; et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 3B silencing in non-small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2004, 23, 3521–3529.

- Loh, K.; Chia, J.A.; Greco, S.; Cozzi, S.-J.; Buttenshaw, R.L.; Bond, C.E.; Simms, L.A.; Pike, T.; Young, J.P.; Jass, J.R.; et al. Bone morphogenic protein 3 inactivation is an early and frequent event in colorectal cancer development. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2008, 47, 449–460.

- Chen, X.-R.; Wang, J.-W.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Ye, Z.-Y. Role of BMP3 in progression of gastric carcinoma in Chinese people. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1409–1413.

- Kim, Y.O.; Hong, I.K.; Eun, Y.G.; Nah, S.-S.; Lee, S.; Heo, S.-H.; Kim, H.-K.; Song, H.-Y.; Kim, H.-J. Polymorphisms in bone morphogenetic protein 3 and the risk of papillary thyroid cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2013, 5, 336–340.

- Kisiel, J.B.; Li, J.; Zou, H.; Oseini, A.M.; Strauss, B.B.; Gulaid, K.H.; Moser, C.D.; Aderca, I.; Ahlquist, D.A.; Roberts, L.R.; et al. Methylated Bone Morphogenetic Protein 3 (BMP3) Gene: Evaluation of Tumor Suppressor Function and Biomarker Potential in Biliary Cancer. J. Mol. Biomark. Diagn. 2013, 4, 1000145.

- Valenzuela, D.M.; Murphy, A.J.; Frendewey, D.; Gale, N.W.; Economides, A.N.; Auerbach, W.; Poueymirou, W.T.; Adams, N.C.; Rojas, J.; Yasenchak, J.; et al. High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 652–659.

- Takahashi, H.; Ikeda, T. Transcripts for two members of the transforming growth factor-beta superfamily BMP-3 and BMP-7 are expressed in developing rat embryos. Dev. Dyn. 1996, 207, 439–449.

- Groppe, J.; Greenwald, J.; Wiater, E.; Rodriguez-Leon, J.; Economides, A.N.; Kwiatkowski, W.; Baban, K.; Affolter, M.; Vale, W.W.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; et al. Structural basis of BMP signaling inhibition by Noggin, a novel twelve-membered cystine knot protein. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2003, 85 (Suppl. 3), 52–58.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Otsuka, F.; Hino, J.; Miyoshi, T.; Takano, M.; Miyazato, M.; Makino, H.; Kangawa, K. Bone morphogenetic protein-3b (BMP-3b) inhibits osteoblast differentiation via Smad2/3 pathway by counteracting Smad1/5/8 signaling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 350, 78–86.

- Wozney, J.M.; Rosen, V.; Celeste, A.J.; Mitsock, L.M.; Whitters, M.J.; Kriz, R.W.; Hewick, R.M.; Wang, E.A. Novel regulators of bone formation: Molecular clones and activities. Science 1988, 242, 1528–1534.

- Goodman, C.A.; Hornberger, T.A.; Robling, A.G. Bone and skeletal muscle: Key players in mechanotransduction and potential overlapping mechanisms. Bone 2015, 80, 24–36.

- Sanger, T.J.; Norgard, E.A.; Pletscher, L.S.; Bevilacqua, M.; Brooks, V.R.; Sandell, L.J.; Cheverud, J.M. Developmental and genetic origins of murine long bone length variation. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol. 2011, 316, 146–161.

- Sims, N.; Dupont, S.; Krust, A.; Clement-Lacroix, P.; Minet, D.; Resche-Rigon, M.; Gaillard-Kelly, M.; Baron, R. Deletion of estrogen receptors reveals a regulatory role for estrogen receptors-β in bone remodeling in females but not in males. Bone 2002, 30, 18–25.

- Cadet, E.R.; Gafni, R.I.; McCarthy, E.F.; McCray, D.R.; Bacher, J.D.; Barnes, K.M.; Baron, J. Mechanisms responsible for longitudinal growth of the cortex: Coalescence of trabecular bone into cortical bone. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2003, 85, 1739–1748.

- Cho, D.-C.; Brennan, H.J.; Johnson, R.W.; Poulton, I.J.; Gooi, J.H.; Tonkin, B.A.; McGregor, N.E.; Walker, E.C.; Handelsman, D.J.; Martin, T.J.; et al. Bone corticalization requires local SOCS3 activity and is promoted by androgen action via interleukin-6. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 806.

- Piemontese, M.; Almeida, M.; Robling, A.G.; Kim, H.-N.; Xiong, J.; Thostenson, J.D.; Weinstein, R.S.; Manolagas, S.C.; O’Brien, C.A.; Jilka, R.L. Old age causes de novo intracortical bone remodeling and porosity in mice. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e93771.

- Birkhold, A.I.; Razi, H.; Duda, G.N.; Weinkamer, R.; Checa, S.; Willie, B.M. The Periosteal Bone Surface is Less Mechano-Responsive than the Endocortical. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23480.

- Jilka, R.L. The relevance of mouse models for investigating age-related bone loss in humans. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 1209–1217.

- Hoshi, K.; Ogata, N.; Shimoaka, T.; Terauchi, Y.; Kadowaki, T.; Kenmotsu, S.-I.; Chung, U.-I.; Ozawa, H.; Nakamura, K.; Kawaguchi, H. Deficiency of insulin receptor substrate-1 impairs skeletal growth through early closure of epiphyseal cartilage. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 214–223.

- Staines, K.A.; Madi, K.; Javaheri, B.; Lee, P.D.; Pitsillides, A.A. A Computed Microtomography Method for Understanding Epiphyseal Growth Plate Fusion. Front. Mater. 2018, 4, 48.