2. Current Insights

Previous studies on Bmp3 largely focused on its effect on trabecular bone, particularly that of the vertebrae. In this study, we examined, for the first time, the effect of the Bmp3 gene on the cortical bone of long bones—the femur and the tibia. Data on the effect of Bmp3 on distal long bones of the lower limb, in particular the tibia, has so far been lacking. In addition, we compared the effect of Bmp3 removal on male and female mice as well as the effect on mice at different stages of postnatal development, providing a more comprehensive overview of the effect of Bmp3 on bone tissue.

The deletion of the

Bmp3 gene was confirmed in P0 mice via the expression of the β-galactosidase enzyme in

Bmp3−/− mice, in which the

LacZ gene sequence was inserted in-frame in the first exon of the

Bmp3 gene [

14,

34]. Previous research demonstrated that

Bmp3 mRNA is expressed in bone, teeth, lungs, kidneys, intestines, and hair follicles [

17,

35]. Using the

LacZ gene reporter we confirmed these results on a protein level, as the activity of the β-galactosidase enzyme was detected in bone, hair follicles, and lungs. Bmp3 was visualized by X-gal staining in the flat bones of the skull, the ribs, and the vertebrae. Interestingly, the reporter signal was most pronounced in the viscerocranium, the base of the skull and the teeth buds. It should be noted that the enzyme activity observed in the intestine could potentially originate from externally ingested bacteria (milk) and not from intestinal cells since the mice samples were collected

postpartum.

Figure 1. Expression of β- (LacZ) in P0 mice. H&E staining shows no abnormalities in Bmp3–/– mice (C) compared to WT (A) mice. X-gal staining shows no LacZ reporter protein in WT (B), while in Bmp3–/– mice (D) localization of LacZ reporter protein can be observed in bone (yellow arrows), hair follicles (red arrows), and lungs (green arrow). X-gal staining was particularly pronounced in the viscerocranium and the base of the skull.

Bmp3−/− mice had no observable defects and developed at the same rate as WT animals. Bone mineralization was examined 14 days after birth, with differential skeleton staining of the mineralized and cartilaginous portion of the skeleton. The long bones of

Bmp3−/− mice were more opaque, indicating a higher cartilage replacement rate and more calcium deposition compared to WT mice. This observation, even at a young age, is in accordance with the role of Bmp3 as a negative bone regulator [

12]. The lack of a major effect of

Bmp3 gene removal on mouse size indicates the existence of redundancy for BMP inhibition during bone growth and development [

36,

37]. Nevertheless, Bmp3 plays a major role in BMP inhibition, mostly due to its abundance [

38].

Figure 2. Differential skeletal staining of long bones in P14 mice. Mineral deposition (white arrows) in the distal femur (A) and proximal tibia (B) appears more pronounced in Bmp3–/– mice compared to WT mice. The effect is the most pronounced in the proximal fibula (yellow arrow) where observable vesicles were present in all WT mice, but not in any of the analyzed Bmp3–/– mice.

Although muscle tissue was not the focus of this research, the fact that no significant difference in body mass was observed between

Bmp3−/− and WT mice warrants further investigation of the possible effect of Bmp3 on skeletal muscles [

39]. Even though excess bone tissue could require more muscle mass for movement, we did not observe any significant changes in body mass in

Bmp3−/− mice, and thus, indirectly no significant increase in muscle mass. This finding could possibly be explained by the predominantly sedentary life of laboratory mice which might cause any existing effects on muscle mass to be less pronounced.

Experimental research has shown that Bmp3 is expressed in the hypertrophic cell layer of the femur growth plate, which supports findings that Bmp3 is involved in trabecular bone growth [

24]. Furthermore, significant effects of genetic manipulation on animal phenotype at a young age were observed in numerous mouse models [

40]. The findings in our study suggest that the differences in bone mineralization in

Bmp3−/− mice observed at P14 may persist until maturity. At P14 we analyzed only male mice due to the fact that sexual dimorphism in bone length in mice is not observed prior to three weeks of age [

40].

Figure 3. Femur cortical and trabecular bone render of 8-week- and 16-week-old female and male Bmp3–/–and WT mice.

Nevertheless, it might be reasonable to assume that functional knockout animals could display differences in bone metabolism between sexes at a mature age due to different responses to sex hormones [

41]. For example, deletion of estrogen receptors reveals a regulatory role for estrogen receptors-beta in bone remodeling in females, but not in males. In addition, Bmp3 could affect male and female mice differently due to sexual dimorphism in mice. In this study, we examined the potential sex differences in Bmp3 bone metabolism regulation by comparing the effects of Bmp3 deletion in both male and female mice. When the effect of mice size on bone volume was eliminated by normalizing it according to tissue volume, a significant increase in bone volume fraction (BV/TV) in

Bmp3−/− mice was observable in both sexes and in both analyzed age groups. This supports the notion that the fundamental inhibitory effect of Bmp3 is similar in both sexes, even though effect size analysis suggests that it might be slightly more pronounced in female mice.

Figure 4. Tibia cortical and trabecular bone render of 8-week- and 16-week-old female and male Bmp3–/–and WT mice.

Since our findings demonstrated a significant effect of Bmp3 on cortical bone volume, it is important to note that the formation of cortical bone comprises of two distinct processes: diaphyseal cortical bone is formed by sub-periosteal apposition, while metaphyseal cortical bone is formed by trabecular coalescence [

42] and is more pronounced in male mice [

43]. Bone corticalization requires local SOCS3 activity and is promoted by androgen action via interleukin-6. In our research, the effect of

Bmp3 deletion on cortical bone parameters followed the same trends in both male and female mice. In general, physiological decrease in femoral cortical thickness occurs in both male and female mice as a result of decreased periosteal formation, increased endosteal resorption, medullary expansion, increased osteocyte DNA damage, cellular senescence, and increased levels of RANKL [

44]. Higher responsiveness of the endocortical bone surface to mechanical loading could also serve as a mechanism for increased bone resorption due to lower animal activity in older age [

45]. In our study, the cortical bone analysis revealed that both male and female

Bmp3−/− mice had, on average, a lower endosteal volume which corresponds to a smaller medullar canal, although the difference was significant only in female mice (16-week-old mice for the femur and both age groups for the tibia). Other studies found that the porosity of the femoral cortical bone in mice increased with age and had a significantly higher incidence in females, which, along with increased endosteal resorption, led to a reduction in cortical thickness in older animals [

46]. In addition,

Bmp3−/− mice in our study had a higher femoral diaphyseal cortical thickness with significant differences for most groups, with the exception of the tibia in 16-week-old mice. The fact that

Bmp3−/− mice had a higher cortical thickness, but a lower endosteal volume suggests that endosteal resorption in

Bmp3−/− mice was decreased compared to WT animals.

In addition to the effect on cortical bone, our study also confirmed the effect of the removal of the

Bmp3 gene on the trabecular bone of long bones in both male and female mice. Trabecular bone analysis of the femur revealed that

Bmp3−/− mice had an approximately two times higher bone volume fraction than WT mice, which is in line with results from previous studies [

11,

12]. A similar trend was observed for the trabecular bone of the tibia, further establishing the effect of the

Bmp3 gene on long bones. From the trabecular parameters that reflect BV/TV, only the trabecular number was shown to have a consistent significant increase in

Bmp3−/− mice. Trabecular thickness increased significantly only in 8-week-old

Bmp3−/− mice, while it decreased in 16-week-old

Bmp3−/− mice, albeit not significantly. Furthermore, the correlation coefficient between bone volume fraction and trabecular number is much higher than the correlation coefficient between bone volume fraction and trabecular thickness. This indicates that the increase in trabecular bone volume in

Bmp3−/− mice is primarily due to an increase in the number of trabeculae, while the changes in trabecular thickness contribute much less to the increase in trabecular bone volume in

Bmp3−/− mice.

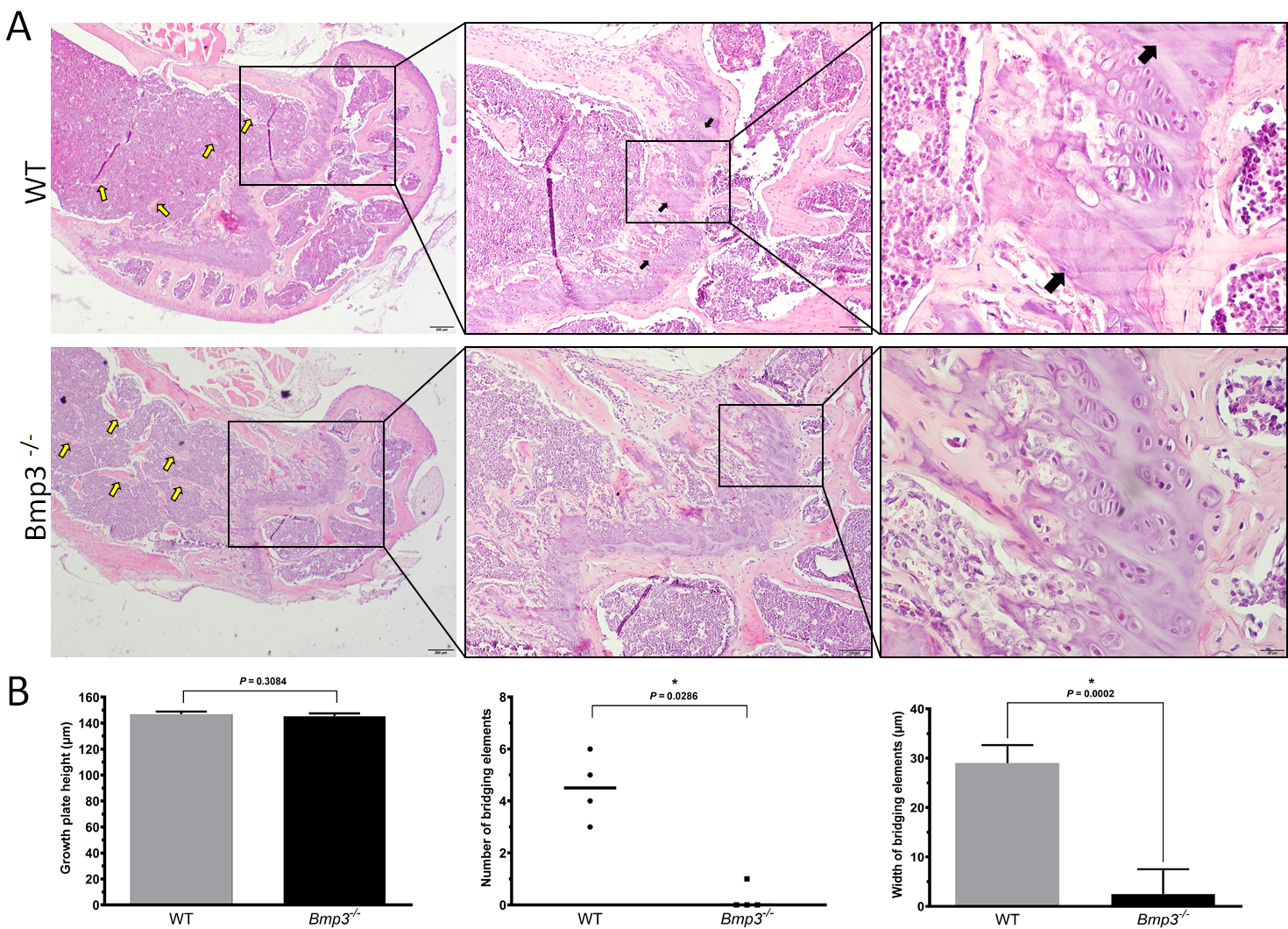

Histological analysis of the distal femur of 16-week-old mice revealed that more trabeculae were present in

Bmp3−/− mice, which was in line with the quantitative findings from the micro-CT analysis. Furthermore, no mineralized cartilage was observed in the epiphyseal growth plate of

Bmp3−/− mice. This finding is relevant because, unlike in humans, the epiphyseal growth plate in mice does not close during puberty [

46], but rather undergoes extensive cartilage mineralization causing plate bridging and subsequent thinning of the growth plate [

47,

48]. We found signs of epiphyseal growth plate bridging only in WT mice, which indicates that the process is either completely absent in

Bmp3−/− mice, or at least significantly delayed not to be observable at 16 weeks of age. It is interesting to note that previous research found

Bmp3 mRNA expression in hypertrophic chondrocytes, but not in other parts of the growth plate [

24]. Altogether, this supports the notion that Bmp3 expression is attenuated prior to chondrocyte differentiation from bone marrow osteoprogenitor cells [

28]. Since there is no difference in the length of long bones between

Bmp3−/− and WT mice, it can be concluded that Bmp3 deficiency does not significantly affect long bone cortical growth, thus, it likely affects neither chondrocyte differentiation nor proliferation. Instead, Bmp3 deficiency appears to primarily affect chondrocyte hypertrophy and extracellular matrix deposition in the epiphyseal region, resulting in increased formation of trabecular bone, with higher expression of Runx2 in that region. This is caused by an excess availability of osteoinductive molecules, such as BMP2 in

Bmp3−/− mice.

Figure 5. Distal femur growth plate in 16-week old mice.

The aforementioned results demonstrated that Bmp3 in mice has a significant role in the regulation of long bone formation, affecting both cortical and trabecular bone respectively. Similar effects of Bmp3 on long bones were observed in both male and female mice, excluding a significant role of sex hormones in the mechanism of its action. These results further corroborate a significant regulatory role of Bmp3 deficiency in bone metabolism leading to an increased trabecular and cortical bone volume of long bones in mice.

3. Conclusions

Bmp3 gene deletion in mice caused an increase in the cortical and trabecular bone volume of the distal femur and proximal tibia, further confirming the inhibitory role of Bmp3 in bone tissue. An increase in bone calcification was observed in P14 Bmp3−/− mice, while an increase in bone volume was observed in 8-weeks- and 16-weeks-old Bmp3−/− mice in both sexes. The increase in cortical bone volume and cortical thickness in Bmp3−/− mice was mostly a consequence of decreased endosteal resorption, while periosteal apposition seemingly remained unaffected. Trabecular bone was increased due to the impaired inhibitory effect of Bmp3 on cartilage to bone transition in the epiphyseal growth plate. Comprehensive analysis of cortical and trabecular bone suggests that Bmp3 antagonizes the effects of osteogenic BMPs in bone, preventing uncontrolled bone formation and offering a mechanical link to growth factor expression in the adaptation of bone to load.