| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roberto Iorio | + 3455 word(s) | 3455 | 2021-12-29 09:32:02 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 3455 | 2022-01-19 03:33:28 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 3455 | 2022-01-19 03:35:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

Mitophagy, the selective removal of dysfunctional mitochondria by autophagy, is critical for regulating mitochondrial quality control in many physiological processes, including cell development and differentiation. On the other hand, both impaired and excessive mitophagy are involved in the pathogenesis of different ageing-associated diseases such as neurodegeneration, cancer, myocardial injury, liver disease, sarcopenia and diabetes. The best-characterized mitophagy pathway is the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)/Parkin-dependent pathway. However, other Parkin-independent pathways are also reported to mediate the tethering of mitochondria to the autophagy apparatuses, directly activating mitophagy (mitophagy receptors and other E3 ligases). In addition, the existence of molecular mechanisms other than PINK1-mediated phosphorylation for Parkin activation was proposed. The adenosine50-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is emerging as a key player in mitochondrial metabolism and mitophagy.

1. Introduction

2. Regulation of Mitophagy

2.1. Chemical and Natural Mitophagy Triggers

In cultured cell lines, it is experimentally advantageous to use chemical reagents to trigger PINK1–Parkin-mediated mitophagy. In this regard, different compounds were described, including many protonophores, inhibitors of the respiratory chain, and novel chemical compounds and naturally occurring substances.

2.2. PINK1–Parkin Axis

The best-known mitochondrial stress signaling pathway is the PINK1–Parkin-driven mitophagy, which mediates the specific ubiquitination and subsequent removal of dysfunctional/damaged mitochondria by recruiting autophagic machinery [12][13].

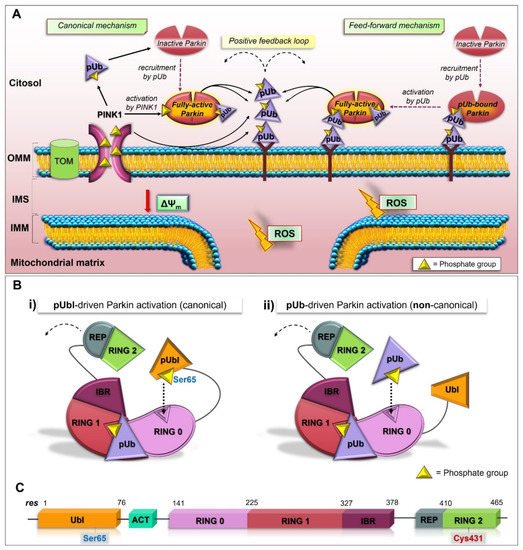

2.3. Structure and Activation of Parkin

PINK1 acts as a mitochondrial damage sensor, and when its import is arrested (under bioenergetics stress, loss in ∆Ψm), it accumulates on the OMM of dysfunctional mitochondria and phosphorylates Ub molecules (pUb). The interaction between pUb and RING1 (at a site consisting of His302 and Arg305) of Parkin leads to the disengagement of the Ubl domain from the core structure, resulting in the conformational rearrangements, which in part liberate Parkin from the inhibitory interactions and promote its accumulation at the surface of mitochondria [14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22]. Therefore, the pUb acts as a receptor for Parkin recruitment [23], and the phosphoserine binding on RING1 govern Parkin localization.

2.4. The Feed-Forward Mechanism of Parkin Activation

The addition of new Ub onto the OMM generates a virtuous circle since the presence of more substrates for PINK1 further increases the content of poly-phosphorylated Ub, leading to the extra activation and recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria. This results in a self-amplifying, feed-forward loop that, at the end, directs mitochondria along the mitophagy pathway.

2.5. Molecular Links between PINK1/Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Dynamics

The Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of Mfn1/2 leads to its proteasomal degradation by a p97-dependent extraction mechanism [24][25][26][27]. Thus, Mfn2 degradation leads to the interdiction of fusion and the induction of fission events as well as to the separation of mitochondria–ER contact sites [27]. The Mfn2 localization in the mitochondria–ER contacts and the detection of PINK1 in MAM (mitochondria-associated membrane) also suggest a PINK1/pUb-mediated Parkin recruitment at the mitochondria–ER sites [28]. Different from the autophagy pathway, mitophagy may exhibit an antagonistic and reciprocal relationship with mitochondria–ER contacts as their reduction is functional to the Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of substrates, its recruitment to the OMM and mitochondrial turnover [28].

2.6. Deubiquitinating Enzymes and PTEN-L as Regulators of Mitophagy

The ubiquitination process is reversible and balanced by the activities of deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), which modulate protein turnover by removing Ub from ubiquitinated substrates. Many DUBs, such as USP15 (Ub-specific cysteine protease 15), USP30, USP33 and USP35 regulate mitochondrial homeostasis and antagonize PINK1-Parkin-driven mitophagy [29][30][31][32][33]. In this regard, a mechanism of action of USP30-mediated K6-linkage-specific deubiquitination was suggested [34][35].

2.7. pUbl-Independent Mechanism of Parkin Activation, the Unexpected Plasticity of RING0 Binding Site

2.8 PINK1 Processing and Stabilization

3. Functions of Mitophagy Receptors

Under physiological and pathological conditions, mitophagy can occur independently of the presence of Parkin. These pathways rely on the intervention of receptors (BNIP3, NIX, FUNDC1, BCL2L13, FKBP8) constitutively localized in the OMM (via the C-terminal transmembrane (TM) domain) and containing a conserved LIR (LC3-interacting region) motif (at N-terminal region), which allows their association with phagophore on its LC3-decorated membrane.

3.1. Other Promoters of Mitophagy: Cardiolipin and Novel E3 Ligases

3.2. Mitophagosome Synthesis: Redundancy and Positive Feedback Signals, and the Role of mTORC1

3.3. AMPK/ULK1 Axis in Mitophagy Cascade

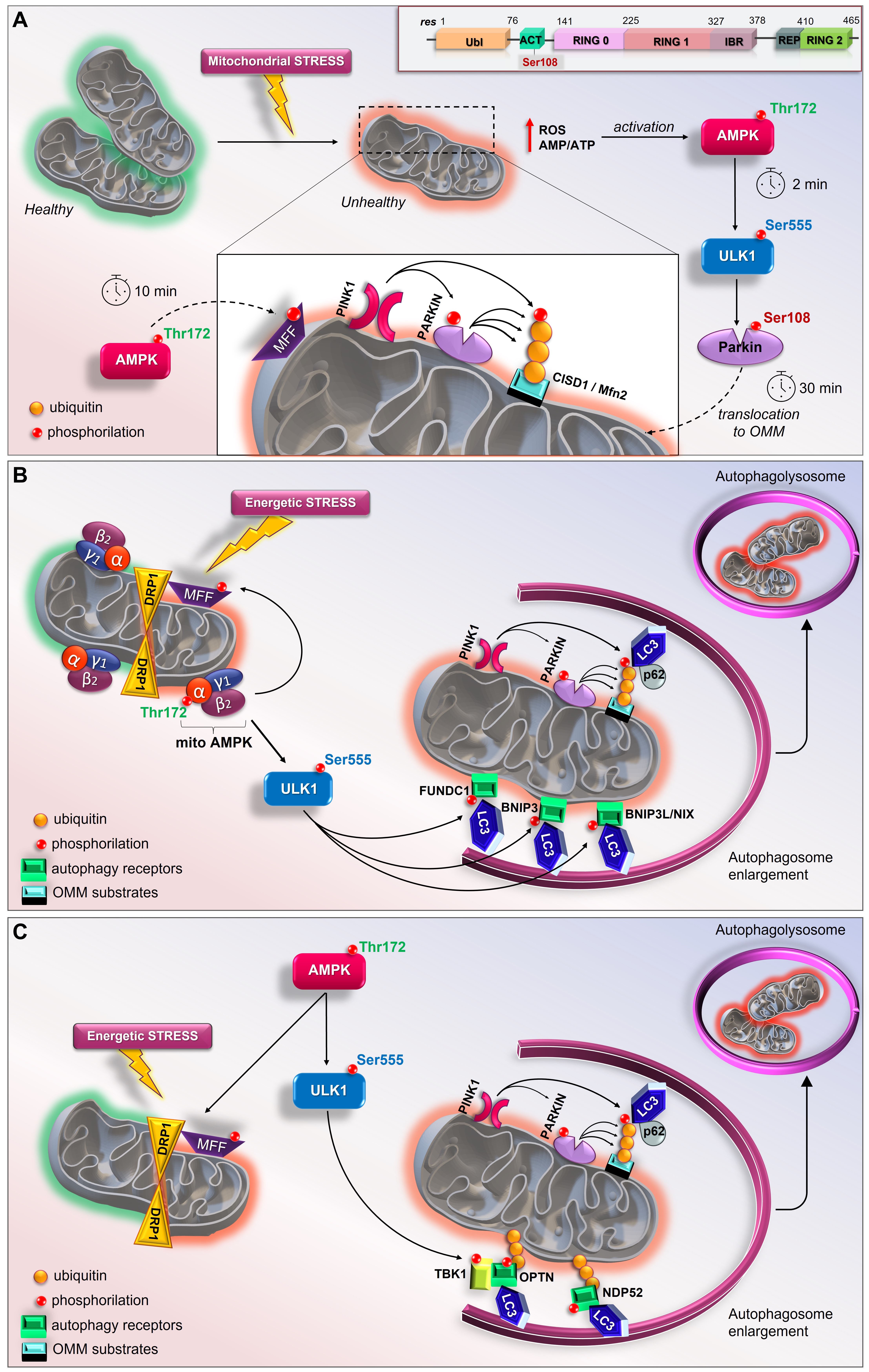

In response to mitochondrial damage, as well as under energetic stress, the AMPK complex (consisting of a catalytic α, a scaffolding β, and a regulatory γ subunit) acts as a sensor. It engages downstream effectors implicated in metabolic processes, autophagy, and in different aspects of mitochondrial homeostasis, including biogenesis, dynamics, and, ultimately, the clearance of damaged mitochondria, to restore homeostasis. Canonically, a radical increase in the cellular AMP/ATP ratio triggers the full activation of AMPK due to AMP/ADP binding to the γ subunit and the subsequent phosphorylation of the Thr172 by the upstream kinase liver kinase B1 (LKB1) [72]. The direct link of AMPK-mediated, energy-sensing function to the autophagy process is represented by the Ser/Thr kinase ULK1 [73]. In addition to ULK1, AMPK also interacts with ATG9 and components of the Class III PI3K complex 1 of the autophagy pathway [72]. ULK1 represents the most upstream activator of the autophagic pathway and is extensively phosphorylated by AMPK [68][74][75][76]. ULK1 is a core constituent of the autophagy pre-initiation complex with ATG101, ATG13, and FIP200. All of these components are substrates of ULK1 kinase activity as well as ULK1 itself. Additional targets of ULK1 were reported, including AMBRA1, VPS34, syntenin-1, TAB2, Raptor, FUNDC1, BNIP3, ATG14, ATG16L, Sec16a, and Sec23a [77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88]. In addition to the autophagy activation, it is becoming more evident that the AMPK/ULK1 axis plays a crucial role in promoting mitophagy [89][90]. Indeed, ULK1- or AMPK-deficient cell lines exhibit an increased accumulation of morphologically altered mitochondria, suggesting that the AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of ULK1 is crucial for the selective clearance of mitochondria [74][91][92]. In this regard, AMPK-mediated ULK1 phosphorylation at Ser555 regulates ULK1 translocation to mitochondria and mitophagy [90][93]. As the proton ionophore CCCP is a strong inducer of PINK1–Parkin-mediated mitophagy and AMPK by ATP depletion, new studies are developing in order to establish which relationship links PINK/Parkin pathway with the AMPK/ULK1 axis. In this regard, exactly how Parkin first senses problems with mitochondria and how specific phosphorylation events orient towards mitophagy remain to be defined [94]. Another important question is how AMPK regulates mitophagy in skeletal muscle. In this regard, new PINK1–Parkin-independent mechanisms and the activation of specific, subcellular AMPK pools were reported [95][96][97].

3.4. The Early Role of the AMPK/ULK1 Axis in Triggering the Rapid Activation of Parkin

As described above, although it is well known that Parkin can sense mitochondrial stress and promote mitophagy, the initial input in dictating the earliest Parkin recruitment remains to be clarified. In this sense, a model revealing the implication of the AMPK-ULK1 axis in starting the first translocation of Parkin onto the OMM was recently proposed in vivo and in vitro (Figure 2A) [94]. In particular, Parkin was reported as a novel ULK1 substrate. Under mitochondrial stress (exposure to CCCP or valinomycin), the immediate activation of cytosolic AMPK (within 2 min) leads to the phosphorylation of its downstream substrates, including ULK Ser555, Raptor Ser 792, MFF Ser146, and ACC Ser79. At the same time, ULK1 activation results in the specific phosphorylation of Parkin Ser108 (P-Parkin-108), an event that seems to be localized in the cytoplasmic region [94]. This phosphorylation falls in a new highly conserved region named the ACT element (activating element). This short region is localized in the flexible linker between the UBL and RING0 domains and is suggested to be critical for Parkin activation (Figure 2A, Top) [98]. Interestingly, phosphoproteomic analyses previously revealed the phosphorylation of Parkin Ser108 in brown fat, although the kinase responsible for this event was not identified identified [99]. In parallel to P-Parkin108, phosphorylations of Beclin Ser30 and ATG16L1 Ser278, two ULK1 substrates [80][86], were also observed. Within 10 min of CCCP exposure, the recruitment of AMPK and ULK1 to mitochondria leads to MFF phosphorylation and mitochondrial fission. Only at later time points (after 30 min) does the phosphorylation of Parkin Ser65 occur. This event coincides with the ubiquitination of the substrates of Parkin, CISD1 and Mfn2, and TBK activation at Ser172 [94]. This study demonstrates that the rapid and greatest PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of Parkin Ser65 requires the ULK1-dependent phosphorylation of Parkin at Ser108. In addition, these findings highlight the crucial and early role played by the AMPK/ULK1 axis in mitophagy and place Parkin regulation downstream of AMPK/ULK1, revealing a new route to modulating Parkin.

3.5. Other Scenarios of AMPK- and ULK1-Mediated Mitophagy

3.6. The Mitochondrial Pool of AMPK (mitoAMPK) Governs the Spatial Specificity of Energetic Stress-Induced Mitophagy

Figure 2. New current models of AMPK/ULK1-mediated mitophagy. (A) Top, schematic representation of primary structure of Parkin showing ACT element with Ser108 residue. In mouse livers and primary hepatocytes AMP/ULK1 axis triggers the rapid activation of Parkin (by Hung et al.) [94]. Upon mitochondrial depolarization, AMP/ATP imbalance and increases in mtROS immediately activate AMPK/ULK1 signaling. Therefore, in the cytoplasm ULK1 phosphorylates Parkin at Ser108 within 2 min of depolarization treatment. Later, AMPK phosphorylates MFF to induce mitochondrial fission and PINK1 phosphorylates Parkin at Ser65; (B) In skeletal muscle, mitoAMPK regulates the spatial specificity of mitophagy in a context of mitochondrial remodeling (by Drake et al.) [97]. Following energetic stress, mitoAMPK is activated in vivo and promotes ULK1-mediated formation of autophagosome which fuse with lysosomes to allow the complete mitochondrial degradation; (C) In C2C12 myotubes, AMPK coordinates mitophagy through mitochondrial fission via MFF and TBK1-mediated autophagosomal engulfment via ULK1 activation (by Seabright et al.) [95].

References

- Palikaras, K.; Lionaki, E.; Tavernarakis, N. Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and pathology. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 1013–1022.

- Smith, M.D.; Harley, M.E.; Kemp, A.J.; Wills, J.; Lee, M.; Arends, M.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Behrends, C.; Wilkinson, S. CCPG1 Is a Non-canonical Autophagy Cargo Receptor Essential for ER-Phagy and Pancreatic ER Proteostasis. Dev. Cell 2018, 44, 217–232.e11.

- Ravenhill, B.J.; Boyle, K.B.; von Muhlinen, N.; Ellison, C.J.; Masson, G.R.; Otten, E.G.; Foeglein, A.; Williams, R.; Randow, F. The Cargo Receptor NDP52 Initiates Selective Autophagy by Recruiting the ULK Complex to Cytosol-Invading Bacteria. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 320–329.e6.

- Turco, E.; Witt, M.; Abert, C.; Bock-Bierbaum, T.; Su, M.-Y.; Trapannone, R.; Sztacho, M.; Danieli, A.; Shi, X.; Zaffagnini, G.; et al. FIP200 Claw Domain Binding to p62 Promotes Autophagosome Formation at Ubiquitin Condensates. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 330–346.e11.

- Pickles, S.; Vigié, P.; Youle, R.J. Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R170–R185.

- Le Guerroué, F.; Eck, F.; Jung, J.; Starzetz, T.; Mittelbronn, M.; Kaulich, M.; Behrends, C. Autophagosomal Content Profiling Reveals an LC3C-Dependent Piecemeal Mitophagy Pathway. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 786–796.e6.

- McWilliams, T.G.; Prescott, A.R.; Allen, G.F.G.; Tamjar, J.; Munson, M.J.; Thomson, C.; Muqit, M.M.K.; Ganley, I.G. mito-QC illuminates mitophagy and mitochondrial architecture in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 214, 333–345.

- Sun, N.; Malide, D.; Liu, J.; Rovira, I.I.; Combs, C.A.; Finkel, T. A fluorescence-based imaging method to measure in vitro and in vivo mitophagy using mt-Keima. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 1576–1587.

- Lee, J.J.; Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Zarate, A.M.; Benincá, C.; Mayor, U.; Clague, M.J.; Whitworth, A.J. Basal mitophagy is widespread in Drosophila but minimally affected by loss of Pink1 or parkin. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 1613–1622.

- McWilliams, T.G.; Prescott, A.R.; Montava-Garriga, L.; Ball, G.; Singh, F.; Barini, E.; Muqit, M.M.K.; Brooks, S.P.; Ganley, I.G. Basal Mitophagy Occurs Independently of PINK1 in Mouse Tissues of High Metabolic Demand. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 439–449.e5.

- Sun, N.; Yun, J.; Liu, J.; Malide, D.; Liu, C.; Rovira, I.I.; Holmström, K.M.; Fergusson, M.M.; Yoo, Y.H.; Combs, C.A.; et al. Measuring In Vivo Mitophagy. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 685–696.

- Narendra, D.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Youle, R.J. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 183, 795–803.

- Youle, R.J.; Narendra, D.P. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 9–14.

- Kumar, A.; Aguirre, J.D.; Condos, T.E.; Martinez-Torres, R.J.; Chaugule, V.K.; Toth, R.; Sundaramoorthy, R.; Mercier, P.; Knebel, A.; Spratt, D.E.; et al. Disruption of the autoinhibited state primes the E3 ligase parkin for activation and catalysis. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2506–2521.

- Kane, L.A.; Lazarou, M.; Fogel, A.I.; Li, Y.; Yamano, K.; Sarraf, S.A.; Banerjee, S.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 205, 143–153.

- Kazlauskaite, A.; Kondapalli, C.; Gourlay, R.; Campbell, D.G.; Ritorto, M.S.; Hofmann, K.; Alessi, D.R.; Knebel, A.; Trost, M.; Muqit, M.M.K. Parkin is activated by PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of ubiquitin at Ser65. Biochem. J. 2014, 460, 127–141.

- Koyano, F.; Okatsu, K.; Kosako, H.; Tamura, Y.; Go, E.; Kimura, M.; Kimura, Y.; Tsuchiya, H.; Yoshihara, H.; Hirokawa, T.; et al. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature 2014, 510, 162–166.

- Ordureau, A.; Sarraf, S.A.; Duda, D.M.; Heo, J.-M.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Sviderskiy, V.O.; Olszewski, J.L.; Koerber, J.T.; Xie, T.; Beausoleil, S.A.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics Reveal a Feedforward Mechanism for Mitochondrial PARKIN Translocation and Ubiquitin Chain Synthesis. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 360–375.

- Kazlauskaite, A.; Martínez-Torres, R.J.; Wilkie, S.; Kumar, A.; Peltier, J.; Gonzalez, A.; Johnson, C.; Zhang, J.; Hope, A.G.; Peggie, M.; et al. Binding to serine 65-phosphorylated ubiquitin primes Parkin for optimal PINK 1-dependent phosphorylation and activation. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 939–954.

- Sauvé, V.; Lilov, A.; Seirafi, M.; Vranas, M.; Rasool, S.; Kozlov, G.; Sprules, T.; Wang, J.; Trempe, J.; Gehring, K. A Ubl/ubiquitin switch in the activation of Parkin. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 2492–2505.

- Wauer, T.; Simicek, M.; Schubert, A.; Komander, D. Mechanism of phospho-ubiquitin-induced PARKIN activation. Nature 2015, 524, 370–374.

- Yamano, K.; Queliconi, B.B.; Koyano, F.; Saeki, Y.; Hirokawa, T.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuda, N. Site-specific Interaction Mapping of Phosphorylated Ubiquitin to Uncover Parkin Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 25199–25211.

- Okatsu, K.; Koyano, F.; Kimura, M.; Kosako, H.; Saeki, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuda, N. Phosphorylated ubiquitin chain is the genuine Parkin receptor. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 209, 111–128.

- Poole, A.C.; Thomas, R.E.; Yu, S.; Vincow, E.S.; Pallanck, L. The Mitochondrial Fusion-Promoting Factor Mitofusin Is a Substrate of the PINK1/Parkin Pathway. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10054.

- Gegg, M.E.; Cooper, J.M.; Chau, K.-Y.; Rojo, M.; Schapira, A.H.V.; Taanman, J.-W. Mitofusin 1 and mitofusin 2 are ubiquitinated in a PINK1/parkin-dependent manner upon induction of mitophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 4861–4870.

- Tanaka, A.; Cleland, M.M.; Xu, S.; Narendra, D.P.; Suen, D.-F.; Karbowski, M.; Youle, R.J. Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 1367–1380.

- McLelland, G.-L.; Goiran, T.; Yi, W.; Dorval, G.; Chen, C.X.; Lauinger, N.D.; Krahn, A.I.; Valimehr, S.; Rakovic, A.; Rouiller, I.; et al. Mfn2 ubiquitination by PINK1/parkin gates the p97-dependent release of ER from mitochondria to drive mitophagy. eLife 2018, 7, e32866.

- Gelmetti, V.; De Rosa, P.; Torosantucci, L.; Marini, E.S.; Romagnoli, A.; Di Rienzo, M.; Arena, G.; Vignone, D.; Fimia, G.M.; Valente, E.M. PINK1 and BECN1 relocalize at mitochondria-associated membranes during mitophagy and promote ER-mitochondria tethering and autophagosome formation. Autophagy 2017, 13, 654–669.

- Cunningham, C.N.; Baughman, J.M.; Phu, L.; Tea, J.S.; Yu, C.; Coons, M.; Kirkpatrick, D.S.; Bingol, B.; Corn, J.E. USP30 and parkin homeostatically regulate atypical ubiquitin chains on mitochondria. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 160–169.

- Bingol, B.; Tea, J.S.; Phu, L.; Reichelt, M.; Bakalarski, C.E.; Song, Q.; Foreman, O.; Kirkpatrick, D.S.; Sheng, M. The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy. Nature 2014, 510, 370–375.

- Cornelissen, T.; Haddad, D.; Wauters, F.; Van Humbeeck, C.; Mandemakers, W.; Koentjoro, B.; Sue, C.; Gevaert, K.; De Strooper, B.; Verstreken, P.; et al. The deubiquitinase USP15 antagonizes Parkin-mediated mitochondrial ubiquitination and mitophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 5227–5242.

- Liang, J.; Martinez, A.; Lane, J.D.; Mayor, U.; Clague, M.J.; Urbé, S. USP 30 deubiquitylates mitochondrial Parkin substrates and restricts apoptotic cell death. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 618–627.

- Niu, K.; Fang, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Tan, Q.; Wei, D.; Li, Y.; Balajee, A.S.; Zhao, Y. USP33 deubiquitinates PRKN/parkin and antagonizes its role in mitophagy. Autophagy 2020, 16, 724–734.

- Gersch, M.; Gladkova, C.; Schubert, A.F.; Michel, M.A.; Maslen, S.; Komander, D. Mechanism and regulation of the Lys6-selective deubiquitinase USP30. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 920–930.

- Sato, Y.; Okatsu, K.; Saeki, Y.; Yamano, K.; Matsuda, N.; Kaiho, A.; Yamagata, A.; Goto-Ito, S.; Ishikawa, M.; Hashimoto, Y.; et al. Structural basis for specific cleavage of Lys6-linked polyubiquitin chains by USP30. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017, 24, 911–919.

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Shen, H.-M. PTEN-L puts a brake on mitophagy. Autophagy 2018, 14, 2023–2025.

- Wang, L.; Cho, Y.-L.; Tang, Y.; Wang, J.; Park, J.-E.; Wu, Y.; Wang, C.; Tong, Y.; Chawla, R.; Zhang, J.; et al. PTEN-L is a novel protein phosphatase for ubiquitin dephosphorylation to inhibit PINK1–Parkin-mediated mitophagy. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 787–802.

- Shiba-Fukushima, K.; Imai, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Ishihama, Y.; Kanao, T.; Sato, S.; Hattori, N. PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of the Parkin ubiquitin-like domain primes mitochondrial translocation of Parkin and regulates mitophagy. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 1002.

- Zhuang, N.; Li, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, T. PINK1-dependent phosphorylation of PINK1 and Parkin is essential for mitochondrial quality control. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2501.

- Tang, M.Y.; Vranas, M.; Krahn, A.I.; Pundlik, S.; Trempe, J.-F.; Fon, E.A. Structure-guided mutagenesis reveals a hierarchical mechanism of Parkin activation. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14697.

- Sauvé, V.; Sung, G.; MacDougall, E.; Kozlov, G.; Saran, A.; Fakih, R.; Fon, E.; Gehring, K. Structural basis for feedforward control in the PINK1/Parkin pathway. bioRxiv 2021.

- Okatsu, K.; Kimura, M.; Oka, T.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuda, N. Unconventional PINK1 localization mechanism to the outer membrane of depolarized mitochondria drives Parkin recruitment. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 964–978.

- Kato, H.; Lu, Q.; Rapaport, D.; Kozjak-Pavlovic, V. Tom70 Is Essential for PINK1 Import into Mitochondria. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58435.

- Sekine, S.; Wang, C.; Sideris, D.P.; Bunker, E.; Zhang, Z.; Youle, R.J. Reciprocal Roles of Tom7 and OMA1 during Mitochondrial Import and Activation of PINK1. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 1028–1043.e5.

- Deas, E.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Gandhi, S.; Desmond, H.; Kjaer, S.; Loh, S.H.Y.; Renton, A.E.M.; Harvey, R.J.; Whitworth, A.J.; Martins, L.M.; et al. PINK1 cleavage at position A103 by the mitochondrial protease PARL. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 867–879.

- Greene, A.W.; Grenier, K.; Aguileta, M.A.; Muise, S.; Farazifard, R.; Haque, M.E.; McBride, H.M.; Park, D.S.; Fon, E.A. Mitochondrial processing peptidase regulates PINK1 processing, import and Parkin recruitment. EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 378–385.

- Jin, S.M.; Lazarou, M.; Wang, C.; Kane, L.A.; Narendra, D.P.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 933–942.

- Meissner, C.; Lorenz, H.; Weihofen, A.; Selkoe, D.J.; Lemberg, M.K. The mitochondrial intramembrane protease PARL cleaves human Pink1 to regulate Pink1 trafficking. J. Neurochem. 2011, 117, 856–867.

- Sekine, S.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 import regulation; a fine system to convey mitochondrial stress to the cytosol. BMC Biol. 2018, 16, 2.

- Yamano, K.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 is degraded through the N-end rule pathway. Autophagy 2013, 9, 1758–1769.

- Liu, Y.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Yin, J.; Erdjument-Bromage, H.; Martin, B.; James, M.; Jiang, X.; Przedborski, S. The Ubiquitination of PINK1 Is Restricted to Its Mature 52-kDa Form. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 30–39.

- Matsuda, N.; Sato, S.; Shiba, K.; Okatsu, K.; Saisho, K.; Gautier, C.A.; Sou, Y.; Saiki, S.; Kawajiri, S.; Sato, F.; et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 211–221.

- Narendra, D.P.; Jin, S.M.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Gautier, C.A.; Shen, J.; Cookson, M.R.; Youle, R.J. PINK1 Is Selectively Stabilized on Impaired Mitochondria to Activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000298.

- Okatsu, K.; Oka, T.; Iguchi, M.; Imamura, K.; Kosako, H.; Tani, N.; Kimura, M.; Go, E.; Koyano, F.; Funayama, M.; et al. PINK1 autophosphorylation upon membrane potential dissipation is essential for Parkin recruitment to damaged mitochondria. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1016.

- Okatsu, K.; Uno, M.; Koyano, F.; Go, E.; Kimura, M.; Oka, T.; Tanaka, K.; Matsuda, N. A Dimeric PINK1-containing Complex on Depolarized Mitochondria Stimulates Parkin Recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 36372–36384.

- Rasool, S.; Soya, N.; Truong, L.; Croteau, N.; Lukacs, G.L.; Trempe, J. PINK 1 autophosphorylation is required for ubiquitin recognition. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e44981.

- Morais, V.A.; Haddad, D.; Craessaerts, K.; De Bock, P.-J.; Swerts, J.; Vilain, S.; Aerts, L.; Overbergh, L.; Grünewald, A.; Seibler, P.; et al. PINK1 Loss-of-Function Mutations Affect Mitochondrial Complex I Activity via NdufA10 Ubiquinone Uncoupling. Science 2014, 344, 203–207.

- Tsai, P.-I.; Lin, C.-H.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Papakyrikos, A.M.; Kim, M.J.; Napolioni, V.; Schoor, C.; Couthouis, J.; Wu, R.-M.; Wszolek, Z.K.; et al. PINK1 Phosphorylates MIC60/Mitofilin to Control Structural Plasticity of Mitochondrial Crista Junctions. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 744–756.e6.

- Chu, C.T.; Ji, J.; Dagda, R.K.; Jiang, J.F.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Kapralov, A.A.; Tyurin, V.A.; Yanamala, N.; Shrivastava, I.H.; Mohammadyani, D.; et al. Cardiolipin externalization to the outer mitochondrial membrane acts as an elimination signal for mitophagy in neuronal cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 1197–1205.

- Li, X.-X.; Tsoi, B.; Li, Y.-F.; Kurihara, H.; He, R.-R. Cardiolipin and Its Different Properties in Mitophagy and Apoptosis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2015, 63, 301–311.

- Fu, M.; St-Pierre, P.; Shankar, J.; Wang, P.T.C.; Joshi, B.; Nabi, I.R. Regulation of mitophagy by the Gp78 E3 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 1153–1162.

- Ambivero, C.T.; Cilenti, L.; Main, S.; Zervos, A.S. Mulan E3 ubiquitin ligase interacts with multiple E2 conjugating enzymes and participates in mitophagy by recruiting GABARAP. Cell. Signal. 2014, 26, 2921–2929.

- Yun, J.; Puri, R.; Yang, H.; Lizzio, M.A.; Wu, C.; Sheng, Z.-H.; Guo, M. MUL1 acts in parallel to the PINK1/parkin pathway in regulating mitofusin and compensates for loss of PINK1/parkin. eLife 2014, 3, e01958.

- Szargel, R.; Shani, V.; Abd Elghani, F.; Mekies, L.N.; Liani, E.; Rott, R.; Engelender, S. The PINK1, synphilin-1 and SIAH-1 complex constitutes a novel mitophagy pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 3476–3490.

- Villa, E.; Proïcs, E.; Rubio-Patiño, C.; Obba, S.; Zunino, B.; Bossowski, J.P.; Rozier, R.M.; Chiche, J.; Mondragón, L.; Riley, J.S.; et al. Parkin-Independent Mitophagy Controls Chemotherapeutic Response in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2846–2859.

- Zachari, M.; Gudmundsson, S.R.; Li, Z.; Manifava, M.; Cugliandolo, F.; Shah, R.; Smith, M.; Stronge, J.; Karanasios, E.; Piunti, C.; et al. Selective Autophagy of Mitochondria on a Ubiquitin-Endoplasmic-Reticulum Platform. Dev. Cell 2019, 50, 627–643.e5.

- Heo, J.-M.; Ordureau, A.; Paulo, J.A.; Rinehart, J.; Harper, J.W. The PINK1-PARKIN Mitochondrial Ubiquitylation Pathway Drives a Program of OPTN/NDP52 Recruitment and TBK1 Activation to Promote Mitophagy. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 7–20.

- Kim, J.; Kundu, M.; Viollet, B.; Guan, K.-L. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 132–141.

- Puente, C.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Jiang, X. Nutrient-regulated Phosphorylation of ATG13 Inhibits Starvation-induced Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 6026–6035.

- Kim, S.G.; Hoffman, G.R.; Poulogiannis, G.; Buel, G.R.; Jang, Y.J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, B.-Y.; Erikson, R.L.; Cantley, L.C.; Choo, A.Y.; et al. Metabolic Stress Controls mTORC1 Lysosomal Localization and Dimerization by Regulating the TTT-RUVBL1/2 Complex. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 172–185.

- Bartolomé, A.; García-Aguilar, A.; Asahara, S.-I.; Kido, Y.; Guillén, C.; Pajvani, U.B.; Benito, M. MTORC1 Regulates both General Autophagy and Mitophagy Induction after Oxidative Phosphorylation Uncoupling. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 37, e00441-17.

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 121–135.

- Lee, J.W.; Park, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Wang, H.-G. The Association of AMPK with ULK1 Regulates Autophagy. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15394.

- Egan, D.F.; Shackelford, D.B.; Mihaylova, M.M.; Gelino, S.; Kohnz, R.A.; Mair, W.; Vasquez, D.S.; Joshi, A.; Gwinn, D.M.; Taylor, R.; et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Connects Energy Sensing to Mitophagy. Science 2011, 331, 456–461.

- Shang, L.; Chen, S.; Du, F.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X. Nutrient starvation elicits an acute autophagic response mediated by Ulk1 dephosphorylation and its subsequent dissociation from AMPK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4788–4793.

- Hoffman, N.J.; Parker, B.L.; Chaudhuri, R.; Fisher-Wellman, K.H.; Kleinert, M.; Humphrey, S.J.; Yang, P.; Holliday, M.; Trefely, S.; Fazakerley, D.J.; et al. Global Phosphoproteomic Analysis of Human Skeletal Muscle Reveals a Network of Exercise-Regulated Kinases and AMPK Substrates. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 922–935.

- Poole, L.P.; Bock-Hughes, A.; Berardi, D.E.; Macleod, K.F. ULK1 promotes mitophagy via phosphorylation and stabilization of BNIP3. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20526.

- Wu, W.; Tian, W.; Hu, Z.; Chen, G.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Xue, P.; Zhou, C.; Liu, L.; et al. ULK1 translocates to mitochondria and phosphorylates FUNDC1 to regulate mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 566–575.

- Gan, W.; Zhang, C.; Siu, K.Y.; Satoh, A.; Tanner, J.A.; Yu, S. ULK1 phosphorylates Sec23A and mediates autophagy-induced inhibition of ER-to-Golgi traffic. BMC Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 22.

- Alsaadi, R.M.; Losier, T.T.; Tian, W.; Jackson, A.; Guo, Z.; Rubinsztein, D.C.; Russell, R.C. ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of ATG16L1 promotes xenophagy, but destabilizes the ATG16L1 Crohn’s mutant. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e46885.

- Rajesh, S.; Bago, R.; Odintsova, E.; Muratov, G.; Baldwin, G.; Sridhar, P.; Rajesh, S.; Overduin, M.; Berditchevski, F. Binding to Syntenin-1 Protein Defines a New Mode of Ubiquitin-based Interactions Regulated by Phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 39606–39614.

- Takaesu, G.; Kobayashi, T.; Yoshimura, A. TGF -activated kinase 1 (TAK1)-binding proteins (TAB) 2 and 3 negatively regulate autophagy. J. Biochem. 2012, 151, 157–166.

- Dunlop, E.A.; Hunt, D.K.; Acosta-Jaquez, H.A.; Fingar, D.C.; Tee, A.R. ULK1 inhibits mTORC1 signaling, promotes multisite Raptor phosphorylation and hinders substrate binding. Autophagy 2011, 7, 737–747.

- Löffler, A.S.; Alers, S.; Dieterle, A.M.; Keppeler, H.; Franz-Wachtel, M.; Kundu, M.; Campbell, D.G.; Wesselborg, S.; Alessi, D.R.; Stork, B. Ulk1-mediated phosphorylation of AMPK constitutes a negative regulatory feedback loop. Autophagy 2011, 7, 696–706.

- Russell, R.C.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, H.; Park, H.W.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Neufeld, T.P.; Dillin, A.; Guan, K.-L. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 741–750.

- Egan, D.F.; Chun, M.G.H.; Vamos, M.; Zou, H.; Rong, J.; Miller, C.J.; Lou, H.J.; Raveendra-Panickar, D.; Yang, C.-C.; Sheffler, D.J.; et al. Small Molecule Inhibition of the Autophagy Kinase ULK1 and Identification of ULK1 Substrates. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 285–297.

- Park, J.-M.; Jung, C.H.; Seo, M.; Otto, N.M.; Grunwald, D.; Kim, K.H.; Moriarity, B.; Kim, Y.-M.; Starker, C.; Nho, R.S.; et al. The ULK1 complex mediates MTORC1 signaling to the autophagy initiation machinery via binding and phosphorylating ATG14. Autophagy 2016, 12, 547–564.

- Joo, J.H.; Wang, B.; Frankel, E.; Ge, L.; Xu, L.; Iyengar, R.; Li-Harms, X.; Wright, C.; Shaw, T.I.; Lindsten, T.; et al. The Noncanonical Role of ULK/ATG1 in ER-to-Golgi Trafficking Is Essential for Cellular Homeostasis. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 491–506.

- Liang, J.; Xu, Z.-X.; Ding, Z.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Werle, K.D.; Zhou, G.; Park, Y.-Y.; Peng, G.; Gambello, M.J.; et al. Myristoylation confers noncanonical AMPK functions in autophagy selectivity and mitochondrial surveillance. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7926.

- Tian, W.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Yan, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhuang, H.; Zhong, W.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.; Lin, C.; et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 by AMPK regulates translocation of ULK1 to mitochondria and mitophagy. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 1847–1854.

- Kundu, M.; Lindsten, T.; Yang, C.-Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, J.; Selak, M.A.; Ney, P.A.; Thompson, C.B. Ulk1 plays a critical role in the autophagic clearance of mitochondria and ribosomes during reticulocyte maturation. Blood 2008, 112, 1493–1502.

- Honda, S.; Arakawa, S.; Nishida, Y.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ishii, E.; Shimizu, S. Ulk1-mediated Atg5-independent macroautophagy mediates elimination of mitochondria from embryonic reticulocytes. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4004.

- Laker, R.C.; Drake, J.C.; Wilson, R.J.; Lira, V.A.; Lewellen, B.M.; Ryall, K.A.; Fisher, C.C.; Zhang, M.; Saucerman, J.J.; Goodyear, L.J.; et al. Ampk phosphorylation of Ulk1 is required for targeting of mitochondria to lysosomes in exercise-induced mitophagy. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 548.

- Hung, C.-M.; Lombardo, P.S.; Malik, N.; Brun, S.N.; Hellberg, K.; Van Nostrand, J.L.; Garcia, D.; Baumgart, J.; Diffenderfer, K.; Asara, J.M.; et al. AMPK/ULK1-mediated phosphorylation of Parkin ACT domain mediates an early step in mitophagy. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg4544.

- Seabright, A.P.; Fine, N.H.F.; Barlow, J.P.; Lord, S.O.; Musa, I.; Gray, A.; Bryant, J.A.; Banzhaf, M.; Lavery, G.G.; Hardie, D.G.; et al. AMPK activation induces mitophagy and promotes mitochondrial fission while activating TBK1 in a PINK1-Parkin independent manner. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 6284–6301.

- Seabright, A.P.; Lai, Y.-C. Regulatory Roles of PINK1-Parkin and AMPK in Ubiquitin-Dependent Skeletal Muscle Mitophagy. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 608474.

- Drake, J.C.; Wilson, R.J.; Laker, R.C.; Guan, Y.; Spaulding, H.R.; Nichenko, A.S.; Shen, W.; Shang, H.; Dorn, M.V.; Huang, K.; et al. Mitochondria-localized AMPK responds to local energetics and contributes to exercise and energetic stress-induced mitophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2025932118.

- Gladkova, C.; Maslen, S.L.; Skehel, J.M.; Komander, D. Mechanism of parkin activation by PINK1. Nature 2018, 559, 410–414.

- Huttlin, E.L.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Elias, J.E.; Goswami, T.; Rad, R.; Beausoleil, S.A.; Villén, J.; Haas, W.; Sowa, M.E.; Gygi, S.P. A Tissue-Specific Atlas of Mouse Protein Phosphorylation and Expression. Cell 2010, 143, 1174–1189.

- Wang, B.; Nie, J.; Wu, L.; Hu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Dong, L.; Zou, M.-H.; Chen, C.; Wang, D.W. AMPKα2 Protects Against the Development of Heart Failure by Enhancing Mitophagy via PINK1 Phosphorylation. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 712–729.

- Lee, S.B.; Kim, J.J.; Han, S.-A.; Fan, Y.; Guo, L.-S.; Aziz, K.; Nowsheen, S.; Kim, S.S.; Park, S.-Y.; Luo, Q.; et al. The AMPK–Parkin axis negatively regulates necroptosis and tumorigenesis by inhibiting the necrosome. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 940–951.

- Pei, S.; Minhajuddin, M.; Adane, B.; Khan, N.; Stevens, B.M.; Mack, S.C.; Lai, S.; Rich, J.N.; Inguva, A.; Shannon, K.M.; et al. AMPK/FIS1-Mediated Mitophagy Is Required for Self-Renewal of Human AML Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 86–100.e6.

- Lu, X.; Xuan, W.; Li, J.; Yao, H.; Huang, C.; Li, J. AMPK protects against alcohol-induced liver injury through UQCRC2 to up-regulate mitophagy. Autophagy 2021, 17, 3622–3643.

- Murakawa, T.; Okamoto, K.; Omiya, S.; Taneike, M.; Yamaguchi, O.; Otsu, K. A Mammalian Mitophagy Receptor, Bcl2-L-13, Recruits the ULK1 Complex to Induce Mitophagy. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 338–345.e6.

- Murakawa, T.; Yamaguchi, O.; Hashimoto, A.; Hikoso, S.; Takeda, T.; Oka, T.; Yasui, H.; Ueda, H.; Akazawa, Y.; Nakayama, H.; et al. Bcl-2-like protein 13 is a mammalian Atg32 homologue that mediates mitophagy and mitochondrial fragmentation. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7527.

- Jang, J.E.; Eom, J.-I.; Jeung, H.-K.; Cheong, J.-W.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Min, Y.H. Targeting AMPK-ULK1-mediated autophagy for combating BET inhibitor resistance in acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Autophagy 2017, 13, 761–762.

- Drake, J.C.; Laker, R.C.; Wilson, R.J.; Zhang, M.; Yan, Z. Exercise-induced mitophagy in skeletal muscle occurs in the absence of stabilization of Pink1 on mitochondria. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 1–6.

- Toyama, E.Q.; Herzig, S.; Courchet, J.; Lewis, T.L.; Losón, O.C.; Hellberg, K.; Young, N.P.; Chen, H.; Polleux, F.; Chan, D.C.; et al. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates mitochondrial fission in response to energy stress. Science 2016, 351, 275–281.

- Zong, Y.; Zhang, C.-S.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Hawley, S.A.; Ma, T.; Feng, J.-W.; Tian, X.; Qi, Q.; et al. Hierarchical activation of compartmentalized pools of AMPK depends on severity of nutrient or energy stress. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 460–473.