| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Astrid Lahousse | + 5092 word(s) | 5092 | 2022-01-05 03:03:56 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 5092 | 2022-01-07 01:58:02 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | -1201 word(s) | 3891 | 2022-01-07 02:13:50 | | |

Video Upload Options

Cancer Survivor (CS), the most widely used definition is: “being a CS, starts on the day of diagnosis and continues until the end of life. Three cancer survivorship phases can be distinguished: “acute survivorship” (i.e., early-stage or time during curative treatment), “permanent survivorship” (i.e., living with cancer or also called the palliative stage), and “extended survivorship” (i.e., cured but not free of suffering). Chronic pain is one of these and occurs in 40% of CSs. Chronic pain is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as pain that persists or recurs for longer than three month. Unrelieved pain can have considerable adverse consequences on a CSs’ quality of life.

1. Introduction

2. Pain

3. Lifestyle Behaviour

3.1. Stress

| Lifestyle Factor | First Author, Year Published, Study Type | Included Population | Number of Included Studies (n1) and Participants (n2) | Detail of Lifestyle Factor/Intervention Assessed | Main Results in Context of the Specified State-of-the-Art | Level of Evidence [46] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol consumption | Leysen et al., 2017, Systematic review with meta-analysis [5] | Breast Cancer Survivors | n1 = 2 (1 CS and 1 C) and n2 = 2519 |

Alcohol use | Alcohol (OR 0.94, 95% CI [0.47, 1.89], p = 0.86, I2 = 67%) was not a predictor for pain, Inconsistent and low evidence |

3b |

| Diet | Kim et al., 2018, Systematic review of systematic reviews [47] | Breast Cancer Survivors with AIA | n1 = 3 (systematic review of RCT), and n2_Omega-3 = 817, and n2_VD = 453 | Omega-3 Fatty Acids, and Vitamin D | Significant effects were found for omega-3 fatty acids (MD −2.10, 95% CI [−3.23, −0.97]), and vitamin D (MD 0.63, 95% CI [0.13, 1.13]) on pain, Low evidence |

1a |

| Yilmaz et al., 2021, Systematic review [48] | Cancer Survivors | n1 = 2 (uncontrolled clinical trial) and n2 = 77 | Nutritional supplements: vitamin C, chondroitin, and glucosamine | Lack of evidence | 2a | |

| Obesity | Leysen et al., 2017, Systematic review with meta-analysis [5] | Breast Cancer Survivors | n1 = 7 (4 CS and 3 C) and n2 = 5573 |

BMI | BMI > 30 (OR 1.34, 95% CI [1.08, 1.67], p = 0.008, I2 = 33%,) was a predictor for pain, Consistent and low evidence |

3b |

| Timmins et al., 2021, Systematic review [49] | Cancer Survivors | n1 = 16 (3 CS, 11 C, and 2 retrospective chart review) and n2 = 14,033 | Obesity | According to the SORT: the association between obesity and CIPN was good-to-moderate patient-centred evidence | 3b | |

| Physical Activity | Boing et al., 2020, Systematic review with meta-analysis [50] | Breast Cancer Survivors with AIA | n1 = 3 (2 RCT, 1 pilot study), and n2 = 118 | Exercise | Significant effect was found on pain (SMD −0.55, 95 % CI [−1.11, −0.00], p = 0.05 I2 = 80%), Low Evidence |

1b |

| Kim et al., 2018, Systematic review of systematic reviews [47] | Breast Cancer Survivors with AIA | n1 = 2 (systematic review of RCT), and n2 = 262 | Aerobic Exercise | No significant effect was found on pain (MD −0.80, 95% CI [−1.33, 0.016]), Low evidence | 1a | |

| Lavín-Pérez et al., 2021, Systematic review with meta-analysis [51] | Cancer Survivors | n1 = 7 (RCT), and n2 = 355 | Exercise (HIT) | Significant effect was found on pain (SMD −0.18, 95% CI [−0.34, −0.02], p = 0.02, I2 = 4%), Moderate evidence | 1a | |

| Lu et al., 2020, Systematic review with meta-analysis [52] | Breast Cancer Survivors with AIA | n1 = 6 (RCT), and n2 = 416 | Exercise | Significant effect was found on pain (SMD −0.46, 95% CI [−0.79, −0.13], p = 0.006, I2 = 63%), Moderate evidence |

1a | |

| Timmins et al., 2021, Systematic review [49] | Cancer Survivors | n1 = 5 (2 C and 3 CS), and n2 = 3950 | Low physical activity | According to the SORT: the association between physical inactivity and CIPN was of moderate evidence | 3b | |

| Sleep | Leysen et al., 2019, Systematic review with meta-analysis [53] | Breast Cancer Survivors | n1 = 4 (2 CS and 2 C) and n2 = 1907 | Sleep Disturbances | Pain was a predictor for sleep disturbances (OR 1.68, 95% CI [1.19, 2.37], p = 0.05, I2 = 55%, after subgroup analysis OR 2.31, 95% CI [1.36, 3.92], p = 0.002, I2 = 27%) |

3b |

| Smoking | Leysen et al., 2017, Systematic review with meta-analysis [5] | Breast Cancer Survivors | n1 = 2 (1 CS and 1 C) and n2 = 2519 |

Smoking status | Smoking (OR 0.75, 95% CI [0.62, 0.92], p = 0.005, I2 = 0%) was not a predictor for pain, Consistent and low evidence | 3b |

| Stress | Syrowatka et al., 2017, Systematic review [37] |

Breast Cancer Survivors | n1 = 12 (6 CS and 6 C) and n2 = 7842 | Distress | Pain was significantly associated with distress: 9/12 studies (75%) | 3b |

| Intervention | Chang et al., 2020, Systematic review with meta-analysis [45] | Breast Cancer Survivors | n1 = 5 (RCT) and n2 = 827 |

Mindfulness-Based interventions | No significant effect was found on pain (SMD −0.39, 95% CI, [−0.81, 0.03], p = 0.07, I2 = 85%), Moderate evidence | 1a |

| Cillessen et al., 2019, Systematic review with meta-analysis [54] | Cancer Patients and Survivors | n1 = 4 (RCT) and n2 = 587 |

Mindfulness-Based interventions | Significant effect was found on pain (ES 0.2, 95% CI [0.04, 0.36], p = 0.16, I2 = 0%), Moderate evidence | 1a | |

| Martinez-Miranda [21] | Breast Cancer Survivors | n1 = 2 (RCT) and n2 = 134 |

Patient Education | No significant effect was found on pain (SMD −0.05, 95% CI [−0.26, 0.17], p = 0.67, I2 = 0%, Low evidence |

1a | |

| Silva et al., 2019, Systematic review [55] | Cancer Survivors | n1 = 4 (4 quasi-experimental studies), and n2 = 522 | Promoting healthy behaviour by mHealth apps | Effect found on pain was inconsistent and of low quality of evidence | 2b |

3.2. Sleep

3.3. Diet

3.3.1 Dietary intake

3.3.2. Obesity

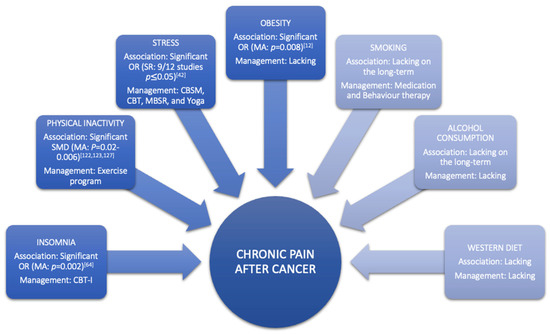

Obesity is a condition characterised by an increase in body fat [75][76]. At the neurobiological level, obesity is considered to cause pain through various mechanisms, including inflammation and hormone imbalance [77]. At the mechanical level, obesity can also cause pain by structural overloading [76][78], which can lead to altered body posture and joint misuse [79]. The latest review in taxane- and platinum-treated CSs demonstrated a good-to-moderate relationship between obesity and higher severity or incidence of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN), with moderate evidence showing diabetes did not increase incidence or severity of CIPN [80]. Furthermore, a systematic review with meta-analyses of Leysen et al., (2017) demonstrated that breast CSs with a BMI > 30 have a higher risk (odds ratio = 1.34, 95% CI 1.08–1.67) of developing pain (Table 1, Figure 2) [12]. However, more research is needed to determine the long-term impact of obesity among the expanding population of CSs [81]. Studies looking at the link between changes in body mass index, fat mass, inflammatory markers, and chronic pain might help us better comprehend the relationship between these variables in the CS population. Additionally, well-designed, high-quality randomised controlled trials on the effect of combined weight loss/pain therapies are required to inform patients and clinicians on how to personalise the approach to reduce chronic pain prevalence, intensity, or severity in CSs through obesity management (Figure 2).

3.4. Smoking

Pain might be one of the barriers to smoking cessation in CSs [82]. An observational study by Aigner et al., (2016) demonstrated that when patients experience higher pain levels, they usually smoke a larger number of cigarettes during these days and initiate fewer attempts to quit smoking [82]. This can be explained by the fact that nicotine produces an acute analgesic effect, making it much harder for them to stop due to the rewarding sensation they experience [83]. Despite its short-term analgesic effect, tobacco smoking sustains pain in the long-term [84]. This underlines the importance of incorporating anti-smoking medications in CSs with pain to avoid relapse during nicotine withdrawal [83]. Moreover, pain management should be added to the counselling aspect to enhance the patient’s knowledge, which in turn, might improve their adherence to the whole smoking cessation program [82]. Furthermore, the 5As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) approach, which assesses the willingness of the patient to quit smoking, is no longer recommended since studies have demonstrated that smokers who did not feel ready to quit smoking at the same rate as those who wanted to [85]. The model with the most promising results might be “opt-out”, during which health care providers offer counselling and pharmacotherapy to all smokers, which is more ethical [86]. However, research on how to integrate this approach in current cancer care for CSs is needed.

3.5. Alcohol Consumption

The impact of alcohol use on pain is poorly investigated in CSs, but according to one systematic review of two cohort studies, the risk of developing pain can be reduced by alcohol use (Table 1) [12]. This finding might be misleading due to the fact that alcohol has an acute analgesic effect [87]. In non-cancer populations, studies demonstrated that this analgesic effect diminishes over time, and there is an association between chronic pain and alcohol consumption [88]. This pain might be evoked by developing alcoholic neuropathy, musculoskeletal disorders, or alcohol withdrawal [88]. Conversely, chronic pain increases the risk of alcohol abuse [89]. Nevertheless, psychosocial factors are also highly present in patients with alcohol abuse and can be attributed to abnormalities in the reward system of the brain [90]. Additionally, a recently published study demonstrated that chronic pain patients with high levels of pain catastrophising are more likely to be heavy drinkers [91]. General advice on alcohol consumption after cancer is currently not possible due to the high variability of results in different CSs. Therefore, health care providers should tailor their advice according to cancer types and patients [92]. Within that view, an overview of recommendations regarding individualised alcohol consumption for each CS type could support clinicians in doing so, yet such evidence-based recommendations are currently lacking (Figure 2).

3.6. Physical Activity

References

- Levit, L.A.; Balogh, E.; Nass, S.J.; Ganz, P. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Bluethmann, S.M.; Mariotto, A.B.; Rowland, J.H. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2016, 25, 1029–1036.

- Zale, E.L.; Maisto, S.A.; Ditre, J.W. Interrelations between pain and alcohol: An integrative review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 37, 57–71.

- Boissoneault, J.; Lewis, B.; Nixon, S.J. Characterizing chronic pain and alcohol use trajectory among treatment-seeking alcoholics. Alcohol 2019, 75, 47–54.

- Maleki, N.; Oscar-Berman, M. Chronic Pain in Relation to Depressive Disorders and Alcohol Abuse. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 826.

- Nieto, S.J.; Green, R.; Grodin, E.N.; Cahill, C.M.; Ray, L.A. Pain catastrophizing predicts alcohol craving in heavy drinkers independent of pain intensity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 218, 108368.

- Rock, C.L.; Doyle, C.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Meyerhardt, J.; Courneya, K.S.; Schwartz, A.L.; Bandera, E.V.; Hamilton, K.K.; Grant, B.; McCullough, M.; et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012, 62, 243–274.

- Meneses-Echávez, J.F.; González-Jiménez, E.; Ramírez-Vélez, R. Effects of supervised exercise on cancer-related fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 77.

- Kessels, E.; Husson, O.; van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M. The effect of exercise on cancer-related fatigue in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 479–494.

- Fuller, J.T.; Hartland, M.C.; Maloney, L.T.; Davison, K. Therapeutic effects of aerobic and resistance exercises for cancer survivors: A systematic review of meta-analyses of clinical trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1311.

- Kim, T.H.; Kang, J.W.; Lee, T.H. Therapeutic options for aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review of systematic reviews, evidence mapping, and network meta-analysis. Maturitas 2018, 118, 29–37.

- Lu, G.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, L. The effect of exercise on aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1587–1596.

- Boing, L.; Vieira, M.C.S.; Moratelli, J.; Bergmann, A.; Guimarães, A.C.A. Effects of exercise on physical outcomes of breast cancer survivors receiving hormone therapy—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2020, 141, 71–81.

- Ballard-Barbash, R.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Siddiqi, S.M.; McTiernan, A.; Alfano, C.M. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: A systematic review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 815–840.

- Hasenoehrl, T.; Palma, S.; Ramazanova, D.; Kölbl, H.; Dorner, T.E.; Keilani, M.; Crevenna, R. Resistance exercise and breast cancer-related lymphedema-a systematic review update and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2020, 28, 3593–3603.

- Geneen, L.J.; Moore, R.A.; Clarke, C.; Martin, D.; Colvin, L.A.; Smith, B.H. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 1, Cd011279.

- Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Mayo, X.; Liguori, G.; Humphreys, L.; Copeland, R.J.; Jiménez, A. Effects of high-intensity training on the quality of life of cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15089.

- Ijsbrandy, C.; Ottevanger, P.B.; Gerritsen, W.R.; van Harten, W.H.; Hermens, R. Determinants of adherence to physical cancer rehabilitation guidelines among cancer patients and cancer centers: A cross-sectional observational study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 15, 163–177.

- Kampshoff, C.S.; Jansen, F.; van Mechelen, W.; May, A.M.; Brug, J.; Chinapaw, M.J.; Buffart, L.M. Determinants of exercise adherence and maintenance among cancer survivors: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 80.

- Ormel, H.L.; van der Schoot, G.G.F.; Sluiter, W.J.; Jalving, M.; Gietema, J.A.; Walenkamp, A.M.E. Predictors of adherence to exercise interventions during and after cancer treatment: A systematic review. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 713–724.

- Spencer, J.C.; Wheeler, S.B. A systematic review of Motivational Interviewing interventions in cancer patients and survivors. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1099–1105.

- Turner, R.R.; Steed, L.; Quirk, H.; Greasley, R.U.; Saxton, J.M.; Taylor, S.J.; Rosario, D.J.; Thaha, M.A.; Bourke, L. Interventions for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 9.

- Veenhof, C.; Köke, A.J.; Dekker, J.; Oostendorp, R.A.; Bijlsma, J.W.; van Tulder, M.W.; van den Ende, C.H. Effectiveness of behavioral graded activity in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee: A randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 55, 925–934.

- Cillessen, L.; Johannsen, M.; Speckens, A.E.M.; Zachariae, R. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychological and physical health outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 2257–2269.

- Duan, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, M. Effects of Mind-Body Exercise in Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 7607161.

- Mendoza, M.E.; Capafons, A.; Gralow, J.R.; Syrjala, K.L.; Suárez-Rodríguez, J.M.; Fann, J.R.; Jensen, M.P. Randomized controlled trial of the Valencia model of waking hypnosis plus CBT for pain, fatigue, and sleep management in patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2017, 26, 1832–1838.

- Marzorati, C.; Riva, S.; Pravettoni, G. Who Is a Cancer Survivor? A Systematic Review of Published Definitions. J. Cancer Educ. 2017, 32, 228–237.

- Mullan, F. Seasons of survival: Reflections of a physician with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1985, 313, 270–273.

- Paxton, R.J.; Jones, L.A.; Chang, S.; Hernandez, M.; Hajek, R.A.; Flatt, S.W.; Natarajan, L.; Pierce, J.P. Was race a factor in the outcomes of the Women’s Health Eating and Living Study? Cancer 2011, 117, 3805–3813.

- Blanchard, C.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Stein, K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: Results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2198–2204.

- Stinson, K.; Tang, N.K.; Harvey, A.G. Barriers to treatment seeking in primary insomnia in the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional perspective. Sleep 2006, 29, 1643–1646.

- Matthews, E.E.; Arnedt, J.T.; McCarthy, M.S.; Cuddihy, L.J.; Aloia, M.S. Adherence to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013, 17, 453–464.

- Bower, P.; Gilbody, S. Stepped care in psychological therapies: Access, effectiveness and efficiency. Narrative literature review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 186, 11–17.

- Zhou, E.S.; Michaud, A.L.; Recklitis, C.J. Developing efficient and effective behavioral treatment for insomnia in cancer survivors: Results of a stepped care trial. Cancer 2020, 126, 165–173.

- Lynch, F.A.; Katona, L.; Jefford, M.; Smith, A.B.; Shaw, J.; Dhillon, H.M.; Ellen, S.; Phipps-Nelson, J.; Lai-Kwon, J.; Milne, D.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of Fear-Less: A Stepped-Care Program to Manage Fear of Cancer Recurrence in People with Metastatic Melanoma. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2969.

- Ma, Y.; Hall, D.L.; Ngo, L.H.; Liu, Q.; Bain, P.A.; Yeh, G.Y. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 55, 101376.

- Hernandez Silva, E.; Lawler, S.; Langbecker, D. The effectiveness of mHealth for self-management in improving pain, psychological distress, fatigue, and sleep in cancer survivors: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 97–107.

- Roberts, A.L.; Fisher, A.; Smith, L.; Heinrich, M.; Potts, H.W.W. Digital health behaviour change interventions targeting physical activity and diet in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 704–719.

- Yang, W.; Williams, J.H.; Hogan, P.F.; Bruinooge, S.S.; Rodriguez, G.I.; Kosty, M.P.; Bajorin, D.F.; Hanley, A.; Muchow, A.; McMillan, N.; et al. Projected supply of and demand for oncologists and radiation oncologists through 2025: An aging, better-insured population will result in shortage. J. Oncol. Pract. 2014, 10, 39–45.

- Chow, R.; Saunders, K.; Burke, H.; Belanger, A.; Chow, E. Needs assessment of primary care physicians in the management of chronic pain in cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 3505–3514.

- Nijs, J.; Wijma, A.J.; Leysen, L.; Pas, R.; Willaert, W.; Hoelen, W.; Ickmans, K.; Wilgen, C.P.V. Explaining pain following cancer: A practical guide for clinicians. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 23, 367–377.

- Binkley, J.M.; Harris, S.R.; Levangie, P.K.; Pearl, M.; Guglielmino, J.; Kraus, V.; Rowden, D. Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment side effects and the prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation for women with breast cancer. Cancer 2012, 118, 2207–2216.

- McGuire, D.B. Occurrence of cancer pain. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogrphs 2004, 2004, 51–56.

- Lexmond, W.; Jäger, K. Psychomteric Properties of the Dutch Version of the Revised Neurophysiology of Pain Questionnaire; Vrije Universiteit Brussel: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; p. 36.

- Bennett, M.I.; Bagnall, A.M.; Closs, S.J. How effective are patient-based educational interventions in the management of cancer pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 2009, 143, 192–199.

- Nijs, J.; Roose, E.; Lahousse, A.; Mostaqim, K.; Reynebeau, I.; De Couck, M.; Beckwee, D.; Huysmans, E.; Bults, R.; van Wilgen, P.; et al. Pain and Opioid Use in Cancer Survivors: A Practical Guide to Account for Perceived Injustice. Pain Physician 2021, 24, 309–317.

- Maindet, C.; Burnod, A.; Minello, C.; George, B.; Allano, G.; Lemaire, A. Strategies of complementary and integrative therapies in cancer-related pain-attaining exhaustive cancer pain management. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 3119–3132.

- Glare, P.A.; Davies, P.S.; Finlay, E.; Gulati, A.; Lemanne, D.; Moryl, N.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Paice, J.A.; Stubblefield, M.D.; Syrjala, K.L. Pain in cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1739.

- Timmins, H.C.; Mizrahi, D.; Li, T.; Kiernan, M.C.; Goldstein, D.; Park, S.B. Metabolic and lifestyle risk factors for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in taxane and platinum-treated patients: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2021, 1–15.

- Boing, L.; Vieira, M.C.S.; Moratelli, J.; Bergmann, A.; Guimarães, A.C.A. Effects of exercise on physical outcomes of breast cancer survivors receiving hormone therapy—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2020, 141, 71–81.

- Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Mayo, X.; Liguori, G.; Humphreys, L.; Copeland, R.J.; Jiménez, A. Effects of high-intensity training on the quality of life of cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15089.

- Lu, G.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, L. The effect of exercise on aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 1587–1596.

- Leysen, L.; Lahousse, A.; Nijs, J.; Adriaenssens, N.; Mairesse, O.; Ivakhnov, S.; Bilterys, T.; Van Looveren, E.; Pas, R.; Beckwée, D. Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disturbances in breast cancersurvivors: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 4401–4433.

- Cillessen, L.; Johannsen, M.; Speckens, A.E.M.; Zachariae, R. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychological and physical health outcomes in cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychooncology 2019, 28, 2257–2269.

- Hernandez Silva, E.; Lawler, S.; Langbecker, D. The effectiveness of mHealth for self-management in improving pain, psychological distress, fatigue, and sleep in cancer survivors: A systematic review. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 97–107.

- Roth, T. Insomnia: Definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2007, 3, S7–S10.

- Savard, J.; Ivers, H.; Villa, J.; Caplette-Gingras, A.; Morin, C.M. Natural course of insomnia comorbid with cancer: An 18-month longitudinal study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3580–3586.

- Johnson, J.A.; Rash, J.A.; Campbell, T.S.; Savard, J.; Gehrman, P.R.; Perlis, M.; Carlson, L.E.; Garland, S.N. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) in cancer survivors. Sleep Med. Rev. 2016, 27, 20–28.

- Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Lin, C.C.; Mariotto, A.B.; Kramer, J.L.; Rowland, J.H.; Stein, K.D.; Alteri, R.; Jemal, A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2016, 66, 271–289.

- Hall, D.L.; Mishel, M.H.; Germino, B.B. Living with cancer-related uncertainty: Associations with fatigue, insomnia, and affect in younger breast cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 2489–2495.

- Carpenter, J.S.; Elam, J.L.; Ridner, S.H.; Carney, P.H.; Cherry, G.J.; Cucullu, H.L. Sleep, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors and matched healthy women experiencing hot flashes. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2004, 31, 591–5598.

- Savard, J.; Davidson, J.R.; Ivers, H.; Quesnel, C.; Rioux, D.; Dupere, V.; Lasnier, M.; Simard, S.; Morin, C.M. The association between nocturnal hot flashes and sleep in breast cancer survivors. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2004, 27, 513–522.

- Gupta, P.; Sturdee, D.W.; Palin, S.L.; Majumder, K.; Fear, R.; Marshall, T.; Paterson, I. Menopausal symptoms in women treated for breast cancer: The prevalence and severity of symptoms and their perceived effects on quality of life. Climacteric 2006, 9, 49–58.

- Desai, K.; Mao, J.J.; Su, I.; Demichele, A.; Li, Q.; Xie, S.X.; Gehrman, P.R. Prevalence and risk factors for insomnia among breast cancer patients on aromatase inhibitors. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 43–51.

- Finan, P.H.; Goodin, B.R.; Smith, M.T. The association of sleep and pain: An update and a path forward. J. Pain 2013, 14, 1539–1552.

- Haack, M.; Simpson, N.; Sethna, N.; Kaur, S.; Mullington, J. Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: Potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 45, 205–216.

- Qaseem, A.; Kansagara, D.; Forciea, M.A.; Cooke, M.; Denberg, T.D. Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, 125–133.

- Perlis, M.L.; Jungquist, C.; Smith, M.T.; Posner, D. Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Insomnia: A Session-by-Session Guide; Springer Science and Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- Zhou, E.S.; Partridge, A.H.; Syrjala, K.L.; Michaud, A.L.; Recklitis, C.J. Evaluation and treatment of insomnia in adult cancer survivorship programs. J. Cancer Surviv. 2017, 11, 74–79.

- Mindell, J.A.; Bartle, A.; Wahab, N.A.; Ahn, Y.; Ramamurthy, M.B.; Huong, H.T.; Kohyama, J.; Ruangdaraganon, N.; Sekartini, R.; Teng, A.; et al. Sleep education in medical school curriculum: A glimpse across countries. Sleep Med. 2011, 12, 928–931.

- Thomas, A.; Grandner, M.; Nowakowski, S.; Nesom, G.; Corbitt, C.; Perlis, M.L. Where are the Behavioral Sleep Medicine Providers and Where are They Needed? A Geographic Assessment. Behav. Sleep Med. 2016, 14, 687–698.

- Stinson, K.; Tang, N.K.; Harvey, A.G. Barriers to treatment seeking in primary insomnia in the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional perspective. Sleep 2006, 29, 1643–1646.

- Matthews, E.E.; Arnedt, J.T.; McCarthy, M.S.; Cuddihy, L.J.; Aloia, M.S. Adherence to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2013, 17, 453–464.

- Mohammadi, S.; Sulaiman, S.; Koon, P.B.; Amani, R.; Hosseini, S.M. Association of nutritional status with quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 7749–7755.