Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Daniel Mota-Rojas | + 5207 word(s) | 5207 | 2021-11-23 10:32:15 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 5207 | 2022-01-05 04:22:23 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mota-Rojas, D. Anthropomorphism on Dog Emotions and Behavior. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17752 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Mota-Rojas D. Anthropomorphism on Dog Emotions and Behavior. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17752. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Mota-Rojas, Daniel. "Anthropomorphism on Dog Emotions and Behavior" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17752 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Mota-Rojas, D. (2022, January 04). Anthropomorphism on Dog Emotions and Behavior. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17752

Mota-Rojas, Daniel. "Anthropomorphism on Dog Emotions and Behavior." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Anthropomorphism is defined as the tendency to attribute human forms, behaviors, and emotions to non-human animals or objects. Anthropomorphism is particularly relevant for companion animals. Some anthropomorphic practices can be beneficial to them, whilst others can be very detrimental. Some anthropomorphic behaviors compromise the welfare and physiology of animals by interfering with thermoregulation, while others can produce dehydration due to the loss of body water, a condition that brings undesirable consequences such as high compensatory blood pressure and heat shock, even death, depending on the intensity and frequency of an animal’s exposure to these stressors.

attachment

behavior

emotions

human–animal interaction

pet clothes

health

welfare

1. Introduction

The term anthropomorphism arises from the Greek anthropos (human) and morphe (form, appearance). It is defined as the act of attributing human characteristics, intentions, motivations, and emotions to non-human animals or objects [1]. An example of this is the teleological ideas that are often linked to anthropomorphic explanations where people confer human-like traits to entities such as divinities the Christian God in 1753. In fact, it may target inanimate natural and artificial objects, natural phenomena, plants, and most commonly, animals [2]. When humans anthropomorphize animals, they attribute to them their own traits, emotions, or intentions. Charles Darwin described this in detail in 1872 [3], pointing out the natural tendency of some people to describe non-human animals as “humanlike” beings. For instance, people may show a greater interest in domestic animals than in insect’ welfare because the latter do not express behaviors similar to humans [4]. On the other hand, this can also be observed in machines such as humanoid robots that represent a technical aspect of anthropomorphism, created with a human-like appearance that could influence the thinking that robots can feel and think like a person [5]. In animals, the tendency to transfer this bonding and attachment may favor or compromise the latter’s welfare.

In extreme cases, non-human animals may be considered “small” or “modified” humans [2], and human needs may be projected onto them. However, this practice may lead to misinterpretation of the actual intentions, motivations, and emotions behind an animal’s behavior, such as believing that a cat is hungry because it meows in front of the refrigerator, that a dog barks to express its desire to play [6], or that Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) who bare their teeth are smiling when, in reality, it is a threat signal. In some cases, misinterpretation of animal behavior may trigger intense human–animal conflicts [2].

Often, anthropomorphic behavior is not supported by scientific knowledge, but rather by the human intrinsic need to relate with someone that is easily understandable and that easily understands us. This may lead to interpretative biases of the animal’s actual state, which are often aimed to satisfy the human need for a certain type of relationship, rather than trying to acknowledge, recognize and appease the animal’s actual emotions, motivations, and intentions [7]. This form of anthropomorphism towards companion animals was accentuated in the 20th century when attributions of this kind emerged naturally and unconsciously as people began to form close bonds with animals that show greater morphological similarity to humans, including companion animals as well as those that have an external physical resemblance to humans, such as apes and monkeys [7].

Urquiza-Haas and Kotrschal [6] attribute anthropomorphizing actions to the biophilic nature of human beings; that is, an implicit connection with animals and, more broadly, with nature in general. They add that animals with phylogenetic, appearance, and behavioral similarities to humans are the ones that tend to be anthropomorphized. This would explain why people anthropomorphize domestic animals, especially the ones with which they maintain close relationships (e.g., pet dogs), that have a childlike appearance, or that present external anatomical structures that facilitate affiliation with humans and produce a desire to protect them. However, this affiliation with domestic animals, dogs above all, also has a biological component that resides in the feelings of fondness that humans often feel towards dogs because of their large round eyes, capacity to gesticulate, and the way they use their limbs to scratch the ground or cover their face [8], all of which generate human empathy. Kaminski et al. [9] support this argument by demonstrating how, through ancestral human–canine interactions, domestic dogs have developed human-like facial expressions. For example, the faculty of retracting the levator anguli oculi medialis (movement AU101) allows dogs to move their eyebrows in a way that simulates the human expression of sadness, so they can adopt an appearance equivalent to that of a child by making their eyes seem larger. This triggers caring behaviors in adults.

Other reasons why humans perform anthropomorphic behaviors with animals include the fact that the way an animal feels and perceives its environment activate the same brain structures in the limbic system and cortical areas [6][10], making it easy to attribute emotions to animals due to similarities to human facial expressions.

2. Clothing and Its Effect on Thermoregulation

The skin performs multiple metabolic functions related to thermoregulation, sensorial perception, and protection. This organ is made up of the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The dermis contains the so-called annexes; that is, hair follicles and sebaceous and sweat glands, while the appendices hold the nails. Dog’s skin pH is the highest of all animal species, ranging from 6.2 to 8.6, with an average of 7.52 [11]. Because of the complexity of the functions that the skin performs, dressing dogs can have adverse effects that compromise their welfare by, for example, forming a barrier that may impede or block adequate thermoregulation and alter the balance between heat gain and loss that regulates body temperature. Textiles also raise moisture levels in the skin and may increase adhesion between the cloth and the animal’s skin, producing discomfort or even cutaneous lesions. In cats, chafing between cloth and skin can be a cause of sensory discomfort [12].

Dressing pets is now an everyday practice, as human families take their companion animals along with them in clothes or costumes that often allude to fictional characters. The risk of compromising their welfare and the health of the pet’s skin is greater when owners feed their dogs prior to, or during a walk, because the metabolic digestion process generates caloric energy that irradiates throughout the body and increases even more due to the exercise performed. Maintaining correct cellular function requires a basal metabolic rate [13], however, dogs are taken for walks even in sunny and hot weather conditions which determine the absorption of a greater caloric load, that ultimately needs to be eliminated. Since dogs lack sweat glands, heat loss mainly occurs through panting, which helps lower body temperature through the evaporation of water from the primary airways. To a lesser extent, heat loss also occurs with the passage of liquids from the rich vascular network of the dermis through the skin [11].

When animals wear clothes, heat accumulates because physiological mechanisms such as cutaneous vasodilatation and panting are insufficient to dissipate it and maintain a stable body temperature. If heat builds up quickly it can cause heatstroke, or even death, in less than an hour [14]. This reaction can be exacerbated when factors such as the hot weather, in addition to clothing, increase a dog’s body temperature and activates the autonomous nervous system (ANS) and its thermoregulatory mechanisms to effectuate peripheral vasodilatation for heat dissipation through furless structures such as limbs and paw pads [15][16][17]. When this mechanism acts inefficiently the dog’s body temperature will increase [18].

In these cases, clothing operates as an additional physical barrier against heat dissipation. When heat does not dissipate, the increase in body temperature accelerates the metabolic rate, which may, in turn, lead to hyperthermia [19]. In Figure 1, thermograms of a dog and cat, with and without clothing, are compared to show the increase in temperature in different thermal regions (ear canal, nose, and lacrimal caruncle) due to the altered thermoregulation. When core temperatures reach 39 °C in dogs and 39.5 °C in cats, thermolysis mechanisms are activated (panting, increased peripheral blood flow) to prevent possible complications such as cerebral edema [18]. Contrary to common belief, the nostrils, rather than the tongue, play a primary role in heat dissipation. This is because the form of the dog’s cornets provides a broad, highly vascularized surface that allows them to lose heat quickly and efficaciously. Canines also have a lateral nasal gland that aids cooling by evaporation, but when used for prolonged periods this mechanism alters the animal’s body water percentage. Therefore, the mechanisms responsible for maintaining thermal neutrality may ultimately affect the animal’s blood pressure, as seen in temperatures above 38 °C, where dogs registered a maximum mean systolic value of 136 mmHg [18].

Figure 1. Comparison of the thermal response of clothing in dogs and cats. (A) Two year-old female dog without a sweater. The region of the auditory canal (El1) has a temperature range between 33.5 °C (red triangle) and 30.5 °C (blue triangle), while in the nasal region (El2) there is a maximum temperature of 32.5 °C (red triangle) and a minimum of 23.7 °C (blue triangle) before wearing a sweater. (B) Thermal pattern of the same canine 8 h after dressing. The increase in maximum temperature by 2.3 °C (red triangle) can be seen in both the auditory canal and the nasal region, although there were no changes in the lacrimal caruncle. (C) Cat without a sweater. The facial region of an 8-year-old Mexican domestic breed cat is displayed, where the lacrimal caruncle (El1), ear canal (El2), and nasal region showed maximum temperatures of 36.2 °C (red triangle), 28.8 °C, and 33.9 °C, respectively, before clothing. (D) Thermal pattern of the same feline 8 h after dressing. The tear caruncle (El1) showed an increase of 1.3 °C (red triangle), while in the ear canal (El2) and the nasal region the temperature increased by 2.7 °C and 1.7 °C (El3), respectively. Both events represent the effect that the use of sweaters has on the thermoregulation of animals by increasing their body temperature. During hot or controlled climates, such as inside a house, hyperthermia can be exacerbated and cause an increase in core temperature by 2 °C.

Hyperthermia due to exercise, high environmental temperatures, or clothing, can cause inflammatory and hemostatic processes (such as coagulation cascade and endotoxemia) that can eventually lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Both usually progress to multiple organ (kidney, brain, skeletal muscle, and liver) dysfunction syndrome (MOD) [14][20], resulting in heatstroke. Brachycephalic breeds such as pugs, boxers, and bulldogs, among others, are especially predisposed to respiratory distress derived from heatstroke because they have stenotic nares, elongated soft palates, and hypoplastic tracheas that perform evaporation inefficiently [14]. It is, then, of primary importance to consider that clothes in dogs can interfere with their thermoregulatory system [15].

This process of thermoregulation is illustrated in Figure 2, where the superficial blood vessels (capillaries) contribute to heat loss and heat retention through vasodilatation and vasoconstriction, respectively [21].

Figure 2. Mechanism of peripheral thermoregulation. The POA responds to a thermal stimulus (cold and hot) activating the thermoregulatory centers located in the hypothalamus. This center promotes mechanisms to dissipate heat or maintain heat through changes in the microcirculation of the skin. When the POA activates cooling mechanisms due to a hot environment, vasodilatation of the superficial capillaries and blood vessels on the limbs produces a heat loss and a decline of the body core temperature. Contrary, when POA activates warming mechanisms in cold settings, the heat conservation, to increase central temperature, is performed by vasoconstriction of these superficial capillaries to shift blood flow to critical organs. POA: preoptic area.

This caloric exchange is triggered by the central nervous system (CNS) and, more specifically, the hypothalamus, in response to the thermal signaling of peripheral receptors (called Ruffini corpuscles) that perceive hot or cold stimulus (see Figure 3). Under certain conditions, and only upon medical recommendation, clothes may protect against hypothermia in cold or freezing environments when shivering thermogenesis is not enough to maintain homeostasis. In all other circumstances, the practice of dressing these animals is counter-indicated.

Figure 3. Control mechanisms to regulate body temperature via feedback. Thermoreceptors (Ruffino corpuscles) located in the periphery of the skin sense thermal inputs that are processed by different pathways, depending on the sensory information. The path from the left represents a situation where thermoreceptors read warm or hot stimuli. This input is conducted to the DRG of the spinal cord and projected to superior brain centers. The neuronal axons located in the LPBd are activated by warming stimulus, and project to the POA and other structures within the POA, such as MnPO and MPO. Before returning to the spinal cord, the input goes through the DMH, the rRPA, and reaches the ventral horn, where sympathetic fibers act on blood vessels and glands to dissipate heat by vasodilatation and sweating. The cooling pathway from the right follows almost the exact pattern, except that when a cooling signal is perceived from the thermoreceptors, the information reaches the POA through LPBel (instead of the LPBd). Additionally, the efferent responses employ sympathetic fibers for the vasoconstriction of the skin vessels to conserve heat, and somatic motor fibers start the thermogenesis in the muscles by shivering. When the core temperature returns to thermal neutrality, these mechanisms are regulated with feedback to hinder their influence on the vasculature and other structures. DMH: dorsomedial hypothalamus; DRG: dorsal root ganglion; IML: intermediolateral cell column; LPBd: lateral parabrachial nucleus (dorsal subregion); LPBel: lateral parabrachial nucleus (external lateral region); MPO: medial preoptic area: MnPO: median preoptic nucleus; POA; preoptic area; rRPA: rostral raphe pallidus nucleus.

3. Restricted Mobility and Consequences for the Locomotor Apparatus

Another anthropomorphic practice when treating a dog like a child consists of impeding their physical activity and movement; for example, holding pets on one’s lap, carrying them in one’s arms or school bags, or transporting them in strollers designed for babies, for long periods. These practices can affect the behavior and welfare of companion dogs, by reducing their freedom of movement and consequently their ability to control environmental stimuli. This may lead to the development of emotional disorders, such as phobias and anxiety. Furthermore, unnatural postures may also have negative physical consequences. When their limbs are flexed dogs may feel a momentary discomfort and over time, they may develop a condition called biomechanical and metabolic syndrome [22]. When animals move naturally, they do so at different speeds and with distinct forms of locomotion—walking, trotting, running—to exercise their musculoskeletal system, which has three main functions: (1) to generate movement and maintain a correct posture through repeated contractions; (2) to store amino acids so that they are available for general metabolism; and (3) to provide carbon to the liver for gluconeogenesis and the production of glucose that is required for its energy needs. In addition, movement requires certain biochemical processes at the muscular level (Figure 4). These processes are affected when anomalies in muscular structure or function exist [23].

Figure 4. Biochemical process for muscle contraction and movement. In the myelinated axon of motor neurons, the action potential arrives at the neuromuscular conjunction of the sarcolemma. This produces the entrance of Ca2+ by opening the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and the increment of intracellular Ca2+ causes ACh to be released from the synaptic vesicle to the synaptic cleft. In the sarcolemma of the muscle, ACh binds to AChR, the action potential travels along the T-tubules. Later, the sarcoplasmic reticulum releases Ca2+ that will bind to troponin and produce the cross-bridge between actin and myosin. This interaction leads to muscle shortening and contraction. ACh: acetylcholine; Ca2+: calcium.

4. Exercise in Inadequate Places and Injuries

Another widely diffused practice is making dogs wear shoes made from various materials to protect their paw pads and prevent erosion of the soles of their feet. However, it is important to understand that dogs’ paw pads are histologically predisposed to endure contact with abrasive surfaces, thanks to their thick corneous stratum. In addition, the superficial fascia of the paw pads contains numerous adipocytes, while the granular layer of the epidermis of the paw pads has a thickness of eight cells, compared to just two in skin covered with fur. In some cases, the stratum lucidus is present in this zone, as it is in the nose. This structure is made up of several layers of non-nucleated keratinized cells and cytoplasmatic organelles. The cytoplasm contains keratin, phospholipids, and eleidin (a protein similar to keratin) but lacks hair follicles and sebaceous glands. There are numerous atrichial glands in the inferior dermis and subcutaneous tissue [11]. These structures buffer wear and tear and prevent injuries to the paw pads. The epidermal surface of the paw pads differs among companion animals, as it is smooth in cats, but papillary and irregular in dogs [24]. Because these are exposed parts of the animal’s body, an external protector such as shoes can cause tissular injuries due to continuous chafing. Hence, making dogs wear shoes should be considered not only unnecessary but also potentially damaging. Indeed, it is important, especially with dogs, to avoid exercise on highly abrasive ground and at high temperatures, such as long walks on the hot concrete or asphalt of city streets, as erosion, heat, or trauma can injure their paw pads, not to mention the risk of heatstroke [25].

In light of this, the suggestion is that owners take their dogs for walks in areas that are less hostile after evaluating the ambient temperature and type of surface. If this is difficult due to the owner’s working hours, then the so-called “5-s test” should be used. This consists in placing the back of one’s hand on the concrete or asphalt for five seconds. If the person cannot withstand the temperature for those 5 s, then her/his dog will not be able to either. Under these conditions, it is better to abstain from walking. If in these conditions the owner decides to put shoes on the dog’s paws, the heat from the pavement will surely pass through and affect the pet’s paw pads [25].

An associated anthropomorphic practice is subjecting dogs to long baths in tubs, but this softens and thins the skin of the paw pads, increasing sensitivity to all types of injury [25]. Instead of putting shoes on their dogs, owners should simply make sure that all activities are performed in accordance with the biology of this species and monitor environmental conditions to avoid harming their pet’s health and physical integrity.

5. Alimentary Modifications and Effects on the Organism

Dogs and cats are carnivores by nature. This means they have a predilection for products of animal origin over vegetable foods [26]. A dog’s taste for certain foods develops between 4–7 weeks of life when its mother teaches initial alimentary habits. Dogs prefer animal proteins, so the viscera, liver, and raw intestines are much more attractive to them than cooked meat. They also prefer fats of animal origin over vegetable sources. Their favorite meats seem to be, in descending order, beef, lamb, horse, and poultry. They also have a taste for moist foods (40–60% of HR) over dry foods [26]. In their natural state canines do not ingest sugar, so they can only acquire a taste for sweet flavors during lactation. Despite these traits, in recent years many owners of domestic animals have chosen to change their pets’ diet to one similar to human alimentation by projecting their philosophical ideas or preferences onto their dogs and cats. Observations show that they feed dogs junk food, candies, chocolate, ice cream, cake, and sodas, among other items, none of which are healthy for humans, much less for companion animals. Dietary modifications can have severe consequences for animal health if they include foods that fail to satisfy the pet’s basics nutritional needs; for example, by eliminating amino acids or essential fatty acids and/or providing inadequate ingestion of total calories.

Dietary variations are nothing new. It is well known that since the domestication of companion animals biochemical and functional changes in the digestive apparatus of the evolutionary ancestors of dogs-wolves have modified their carnivorous stomach and increased their capacity to digest starch. In fact, consumption of kibble shows that dogs have digestibilities greater than 98% for simple carbohydrates such as monosaccharides (e.g., glucose, fructose), disaccharides (e.g., maltose), sucrose, and lactose, among others [27]. With respect to grains such as rice and corn, figures indicate digestibility levels close to 90% [28]. Studies of dogs have demonstrated that the presence of genes involved in synthetizing digestive enzymes and translation factors of several proteins associated with the digestion of starch differs from that of wild wolves [29]. These findings reveal an evolutionary adaptation in human–animal interaction [30]. Despite this capacity to digest carbohydrates, feeding dogs inappropriate diets with high starch content will considerably worsen health problems. Another factor to consider is that dogs are gluttonous; that is, an innate desire that can lead them to eat several times a day [26]. This can result in problems of obesity due to a high consumption of carbohydrates, especially if coupled with sedentism. This health problem is often diagnosed in clinical veterinary medicine today.

Writing on this form of malnutrition, Van Herwijnen et al. [31] stated that problems such as obesity and malnutrition which reduce the welfare of domestic animals are a consequence of incorrect alimentation. This can range from diets based on bones and raw foods (BARF) that, in the absence of appropriate sanitary handling, can introduce pathogens that affect animal health, to the extreme of giving vegan diets that produce a nutritional deficit in animals, especially dogs and cats that belong to the order carnivores. Malnutrition can also cause metabolic problems. We know, for instance, that it is essential to supplement a cat’s vegan diet with taurine because this important amino acid exists only in meat. This form of supplementation may also be advisable for dogs since studies have determined that deficiencies of nutrients such as taurine and carnitine can cause dilated cardiomyopathy. Research on breeds such as the cocker spaniel, beagle, and golden retriever have shown cardiovascular benefits when animals receive these supplements even when a deficiency of both chemicals remains to be clinically documented [32]. For these reasons, dogs and cats that are fed vegan diets require supplements to remedy these deficiencies [33][34][35][36]. Unfortunately, pet owners are often unaware of these data and unintentionally jeopardize the appropriate functioning of their pet’s organism.

6. Effects of Anthropomorphism on Dog Emotions and Behavior

To date, there is no scientific consensus about the effects of anthropomorphism on companion dogs’ psychological well-being. Previous studies suggest that anthropomorphic thinking may result in a more positive attitude towards general animal welfare issues [37]. For example, anthropomorphizing dogs and the empathy that can surge from it, influences the perception of pain and animal suffering, and owners tend to recognize this adverse effect and acknowledge the importance of its mitigation to preserve their welfare [38]. Moreover, empathy and viewing them as species that can develop human-like feelings determine how people treat and care for them [39]. Nonetheless, its practical application in everyday human–animal interactions is often regarded as a possible threat to the well-being of the animals involved.

Surprisingly, the literature on the effects of anthropomorphic practices on the emotional wellbeing of pets is still scarce and the findings are conflicting. A dated study by Voith et al. [40] failed to demonstrate that anthropomorphized pet dogs displayed more problematic behaviors than dogs that were not usually treated like a person. On the contrary, they found that dogs that experienced some anthropomorphic behaviors had fewer behavior problems. However, the majority of the anthropomorphic attitudes this study investigated referred to owners’ spoiling tendencies that do not necessarily entail an actual anthropomorphic thinking, such as sharing the bed or furniture with companion animals, celebrating the dog’s birthdays, sharing food from the table, etc. [40]. For instance, allowing the dog on the bed may not be driven by an anthropomorphic view of the animal, but rather by the owner’s own pleasure or by the assumption that the dog will be more comfortable on the bed than on the floor, which is hard to deny.

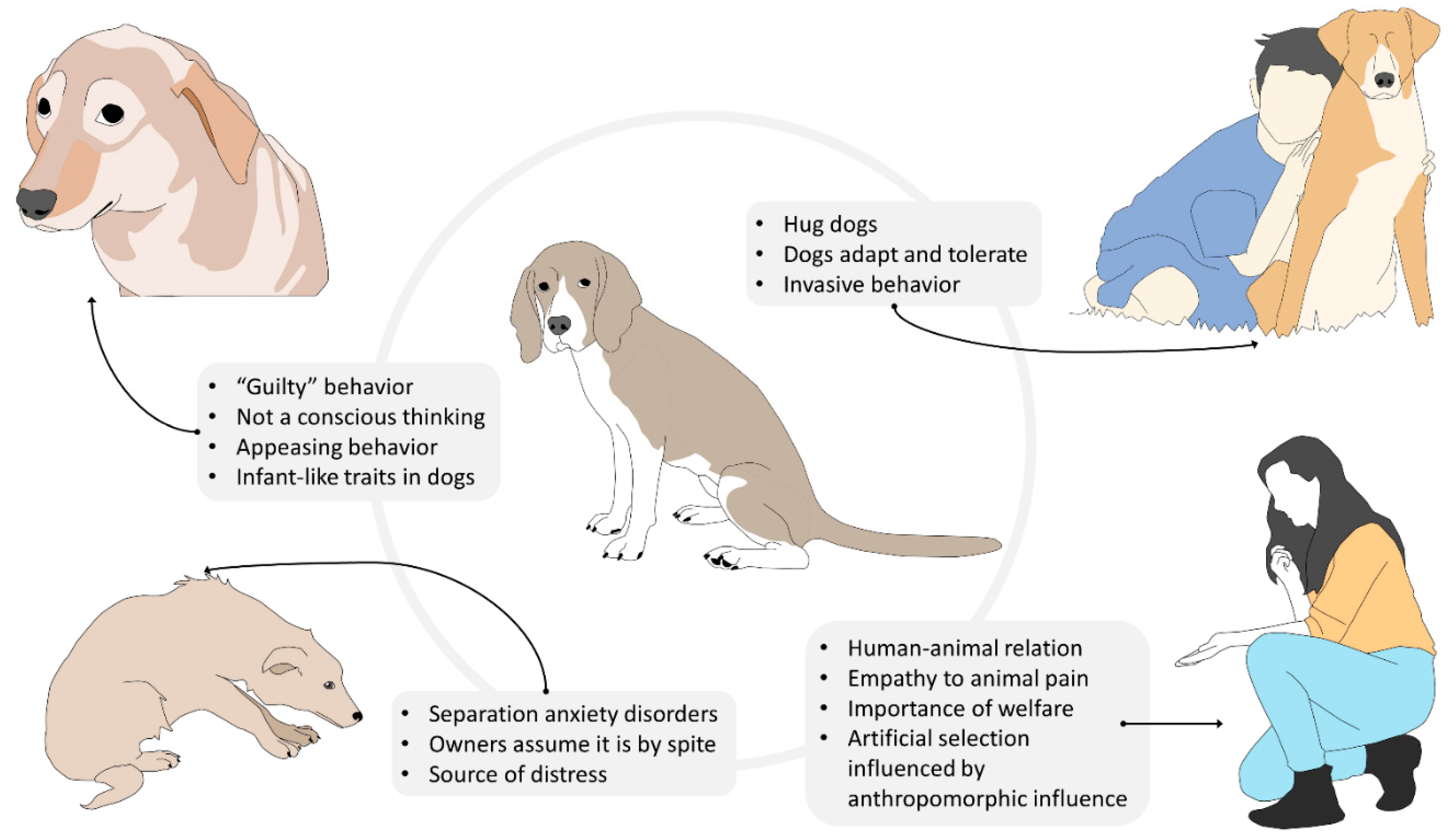

Nevertheless, it is equally undeniable that attributing human mental and emotional states to a dog may lead to anthropocentric misinterpretations of its behavior, which may result in turn to interspecific interactions that may negatively affect the animal’s welfare [41]. A practical example of the risks of dog owners’ anthropocentric attitude is provided by the common belief that dogs are capable of complex feelings, such as guilt [42]. According to Hecht et al. [43], guilt is a self-conscious, evaluative emotion that arises from one’s own perception of having violated an established rule. The most common scenario in which owners attribute such emotion to their pets is that of a dog who, after having been left alone at home and having performed destructive behavior because of anxiety, fear, or boredom, displays submissive and fearful postures when the owner returns. For many owners, these postures are an indication that the dog is aware of having misbehaved during their absence. However, previous studies demonstrated that dogs display “guilty” behavior even when they are not responsible for the undesirable event [44]. Furthermore, findings by Horowitz et al. [45] suggest that what is commonly considered as “guilty behavior” is instead the dog’s response to their owners’ behavior at reunion (i.e., scolding). Furthermore, Hecht et al.’s [43] experiment revealed that the greeting behavior of dogs that transgressed in the owner’s absence does not differ from that of dogs that did not. These results suggest that domestic canine’s “guilty” behavior in the context described does not associate with their awareness of the transgression, but rather with an attempt to appease the owner’s aggressive demeanor during reunion [45]. When interactions of this kind occur repeatedly, the dog may develop anxiety in anticipation of the owner’s return and display appeasement behaviors even in the absence of the owner’s aggressive cues.

In this context, it is clear how anthropomorphism may have a negative impact on companion dogs’ emotional well-being. This is especially true for those subjects that suffer from separation anxiety disorders, for which the owner’s return should represent the solution to their emotional distress. Unfortunately, many owners do not limit themselves to misinterpreting the dog’s appeasement behavior as an expression of guilt, but they also anthropocentrically assume that the destructive behavior carried out by the dog during their absence is motivated by spite rather than panic [44]. Obviously, these owners are more prone to punish their dogs for their destructive behaviors [46], transforming themselves from a potential source of safety and reassurance to an additional source of distress.

Indeed, this vicious circle may have detrimental effects on the dog–owner relationship and on the quality of the dog attachment bond to the owner, which is mainly determined by the ability of the latter to provide safety in conditions of emotional distress [47][48][49]. The owner’s failure to be a source of safety to their dog may result in the development of an insecure attachment style [48][49][50], which, in the human psychiatric literature, has been linked to a variety of psychopathological disorders, such as anxiety [51][52], depression [53], panic [54], aggressiveness [55], and obsessive-compulsive disorders [56].

Anthropomorphism may also lead to the owner’s misunderstanding of the dog’s feelings during supposedly positive interactions. For instance, many owners hug their dogs during affiliative interactions. However, hugging is a human expression of affection that may not be well tolerated by some dogs [57]. While some companion dogs may adapt to their owner’s manifestations of affection, others may still perceive hugging as a very invasive behavior that limits their ability to control the environment. Furthermore, hugging is often associated with the act of bending over the dog or with face-to-face proximity or contact, which may be interpreted as threatening behaviors by the animal. Therefore, it is not surprising that most dog bites in the facial region are preceded by this type of human affiliative interaction [58]. Even in the absence of an aggressive response, the dog may still display stress signals (e.g., head-turning, lip-licking, yawning, etc.) that testify to its discomfort in being forced into such interactions [59], which often occur on a daily basis. Bite prevention programs that highlight the differences between dog and human perception of affective displays and interactions may be extremely useful not just to reduce the risk of injuries [60][61][62], but also to avoid behaviors that may negatively affect dogs’ psychological well-being [59].

The impact of anthropomorphism on dogs’ psychological welfare is not limited to the emotional consequences of daily inappropriate interactions with humans. In fact, for many dog breeds, the whole artificial selection process has been strongly influenced by anthropomorphic tendencies [63]. Too often, selecting dogs for physical and behavioral characteristics facilitates assigning human mental states to them that may seriously compromise dog welfare. The most infamous and evident case is that of brachycephalic breeds. In these dogs, artificial selection has focused on emphasizing human infant-like traits, such as flat faces, round cheeks, large eyes, short extremities, and even clumsiness in movements [64]. The consequence of these paedomorphic features is the emergence of the brachycephalic obstructive airways syndrome (BOAS) that compromises the efficacy of numerous vital functions, such as breathing, tissue oxygenation, thermoregulation and digestion [64][65][66], and ultimately reduces these individuals’ quality of life. Furthermore, the abnormal physical features of brachycephalic dogs may negatively affect their mimic skills and consequently compromise their ability to communicate with conspecifics [67]. Indeed, this may lead to serious intraspecific conflicts that not only jeopardize these dogs’ physical integrity but also decrease their possibilities to experience a normal and fulfilling intraspecific social life [67] (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Influence of anthropomorphism on dog emotion, coping, and human–animal relations. The way humans interact and perceive animal emotions and behaviors can lead to misinterpretations of the motivation and intention of the animal, creating social consequences for them; however, when humans and their companion animal share a close bond, this can encourage empathy and the interest in their welfare.

In general, dog breeds that have been selected for infant-like traits and infant-like sizes are more likely to prompt their owners to exhibit protective behaviors, exactly as a child would do with a parent. Unfortunately, some of these behaviors, such as impeding interactions with other dogs and carrying dogs around in bags or in the owner’s arms can hinder the dog’s cognitive and emotional development. These practices limit the amount of experiences dogs can make in daily life and consequently limit their ability to find strategies to cope with environmental and social stimuli. In other words, these dogs are prevented from adequately developing their skills to adapt to external changes. As a consequence, even the slightest stressor may be perceived as an insurmountable challenge.

Furthermore, by limiting the dog’s movements, these practices affect the dog’s self-perception of control over the environment. Actual or perceived lack of control over external events has long been identified as one of the major triggers for the development of panic and anxiety disorders in both humans and companion animals [68].

While on the one hand anthropomorphism may foster human empathy towards non-human animals [69][70] and consequently promote a positive attitude towards animal welfare, on the other hand, it may have deleterious effects on companion animals’ emotional well-being. However, anthropomorphism is a natural tendency of humans that obligatorily shape their perception of other animal species and that cannot be completely avoided. Hence, in order to protect companion animals from extreme or deleterious anthropomorphic tendencies, education programs aimed to increase dog owners’ scientific knowledge of some easily misinterpretable dog behaviors should be more frequently implemented [71].

References

- Guthrie, S. Anthropomorphism. In Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions; Runehov, A., Oviedo, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 111–113.

- Sueur, C.; Forin-Wiart, M.-A.; Pelé, M. Are They Really Trying to Save Their Buddy? The Anthropomorphism of Animal Epimeletic Behaviours. Animals 2020, 10, 2323.

- Darwin, C. The expression of the emotions in man and animals (1872). In The Portable Darwin; CiNii—National Institute of Informatics: Tokyo, Japan, 1993; pp. 364–393.

- Van Huis, A. Welfare of farmed insects. J. Insects Food Feed 2019, 5, 159–162.

- Tondu, B. Anthropomorphism and service humanoid robots: An ambiguous relationship. Ind. Robot Int. J. 2012, 39, 609–618.

- Urquiza-Haas, E.G.; Kotrschal, K. The mind behind anthropomorphic thinking: Attribution of mental states to other species. Anim. Behav. 2015, 109, 167–176.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Orihuela, A.; Strappini, A.; Cajiao, M.N.; Aguera, E.; Mora-Medina, P.; Ghezzi, M.D.; Alonso, S.M. Teaching animal welfare in veterinary schools in Latin America. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2018, 6, 131–140.

- Horowitz, A.C.; Bekoff, M. Naturalizing Anthropomorphism: Behavioral Prompts to Our Humanizing of Animals. Anthrozoos 2007, 20, 23–35.

- Kaminski, J.; Waller, B.M.; Diogo, R.; Hartstone-Rose, A.; Burrows, A.M. Evolution of facial muscle anatomy in dogs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 14677–14681.

- Paul, E.S.; Mendl, M.T. Animal emotion: Descriptive and prescriptive definitions and their implications for a comparative perspective. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 205, 202–209.

- Castellanos, G.C.; Rodríguez, G.; Iregui, C.A. Estructura histológica normal de la piel del perro (Estado del arte). Rev. Med. Vet. (Bogota) 2005, 1, 109–122.

- Tang, K.-P.M.; Chau, K.-H.; Kan, C.-W.; Fan, J. Assessing the accumulated stickiness magnitude from fabric–skin friction: Effect of wetness level of various fabrics. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180860.

- Robinson, N. Thermoregulation. In Cunningham’s Textbook of Veterinary Physiology; Bradley, G., Ed.; Elsevier España SL: Barcelona, Spain, 2014; pp. 559–568.

- Bruchim, Y.; Horowitz, M.; Aroch, I. Pathophysiology of Heatstroke in Dogs—Revisited. Temperature 2017, 4, 356–370.

- Foley, C. How to Prevent Heat Stroke in Dogs—Whole Dog Journal. Available online: https://www.whole-dog-journal.com/care/how-to-prevent-heat-stroke-in-dogs/ (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Casas-Alvarado, A.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; Mora-Medina, P.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Verduzco-Mendoza, A.; Reyes-Sotelo, B.; Martínez-Burnes, J. Advances in infrared thermography: Surgical aspects, vascular changes, and pain monitoring in veterinary medicine. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 92, 102664.

- Villanueva-garcía, D.; Mota-rojas, D.; Olmos-, A. Hypothermia in newly born piglets: Mechanisms of thermoregulation and pathophysiology of death. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2020, 9, 2112.

- Cainzos, R.P.; Koscinczuk, P.; Ferreiro, M.C. Influencia de la temperatura ambiental sobre la presión arterial del perro. Rev. Vet. 2014, 25, 154.

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Miranda-Córtes, A.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Mora-Medina, P.; Boscato, L.; Hernández-Ávalos, I. Neurobiology and modulation of stress- induced hyperthermia and fever in animals. Abanico. Vet. 2021, 11, 1–17.

- Bruchim, Y.; Loeb, E.; Saragusty, J.; Aroch, I. Pathological Findings in Dogs with Fatal Heatstroke. J. Comp. Pathol. 2009, 140, 97–104.

- Reyes-Sotelo, B.; Mota-Rojas, D.; Martínez-Burnes, J.; Olmos-Hernández, A.; Hernández-Ávalos, I.; José, N.; Casas-Alvarado, A.; Gómez, J.; Mora-Medina, P. Thermal homeostasis in the newborn puppy: Behavioral and physiological responses. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2021, 9, 1–25.

- Holiday, B. Why you Shouldn’t Carry Your Small Dog. Available online: https://holidaybarn.com/blog/dangers-of-carrying-your-small-dog/ (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Shelton, G.; Cardinet, G. Pathophysiologic basis of canine muscle disorders. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1987, 1, 36–44.

- Miller, W.H.; Griffin, C.E.; Campbell, K.L. Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th ed.; Elsevier: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2012; pp. 1–948.

- Viasus, P. Patitas: Sistemas Termosensibles de Prevención, Cuidado y Recuperación de Lesiones en Animales de Compañía Caninos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Bogotá, Bogota, Colombia, May 2020.

- Desachy, F. La Alimentación del Perro; De Vecchi, S., Ed.; De Vecchi Ediciones: Cuauhtémoc, Mexico, 2018; pp. 1–140.

- Carciofi, A.C.; Takakura, F.S.; De-Oliveira, L.D.; Teshima, E.; Jeremias, J.T.; Brunetto, M.A.; Prada, F. Effects of six carbohydrate sources on dog diet digestibility and post-prandial glucose and insulin response. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2008, 92, 326–336.

- Fortes, C.M.L.S.; Carciofi, A.C.; Sakomura, N.K.; Kawauchi, I.M.; Vasconcellos, R.S. Digestibility and metabolizable energy of some carbohydrate sources for dogs. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2010, 156, 121–125.

- Axelsson, E.; Ratnakumar, A.; Arendt, M.-L.; Maqbool, K.; Webster, M.T.; Perloski, M.; Liberg, O.; Arnemo, J.M.; Hedhammar, Å.; Lindblad-Toh, K. The genomic signature of dog domestication reveals adaptation to a starch-rich diet. Nature 2013, 495, 360–364.

- Arendt, M.; Cairns, K.M.; Ballard, J.W.O.; Savolainen, P.; Axelsson, E. Diet adaptation in dog reflects spread of prehistoric agriculture. Heredity 2016, 117, 301–306.

- Van Herwijnen, I.R.; Corbee, R.J.; Endenburg, N.; Beerda, B.; van der Borg, J.A. Permissive parenting of the dog associates with dog overweight in a survey among 2303 Dutch dog owners. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237429.

- Sanderson, S.L. Taurine and Carnitine in Canine Cardiomyopathy. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2006, 36, 1325–1343.

- Beynen, A. Vegetarian petfoods. Creat. Companion 2015, 51, 50–51.

- Overgaauw, P.A.M.; Vinke, C.M.; van Hagen, M.A.E.; Lipman, L.J.A. A One Health Perspective on the Human–Companion Animal Relationship with Emphasis on Zoonotic Aspects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3789.

- Knight, A.; Leitsberger, M. Vegetarian versus Meat-Based Diets for Companion Animals. Animals 2016, 6, 57.

- Zafalon, R.V.A.; Risolia, L.W.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Ayres Rodrigues, R.B.; Pedrinelli, V.; Teixeira, F.A.; Rentas, M.F.; Perini, M.P.; Alvarenga, I.C.; Brunetto, M.A. Nutritional inadequacies in commercial vegan foods for dogs and cats. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227046.

- Butterfield, M.E.; Hill, S.E.; Lord, C.G. Mangy mutt or furry friend? Anthropomorphism promotes animal welfare. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 957–960.

- Ellingsen, K.; Zanella, A.J.; Bjerkås, E.; Indrebø, A. The Relationship between empathy, perception of pain and attitudes toward pets among Norwegian dog owners. Anthrozoos 2010, 23, 231–243.

- Travain, T.; Colombo, E.S.; Heinzl, E.; Bellucci, D.; Prato Previde, E.; Valsecchi, P. Hot dogs: Thermography in the assessment of stress in dogs (Canis familiaris)—A pilot study. J. Vet. Behav. 2015, 10, 17–23.

- Voith, V.L.; Wright, J.C.; Danneman, P.J. Is there a relationship between canine behavior problems and spoiling activities, anthropomorphism, and obedience training? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1992, 34, 263–272.

- Rooney, N.; Bradshaw, J. Canine welfare science: An antidote to sentiment and myth. In Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior: The Scientific Study of Canis Familiaris; Horowitz, A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 241–274.

- Morris, P.H.; Doe, C.; Godsell, E. Secondary emotions in non-primate species? Behavioural reports and subjective claims by animal owners. Cogn. Emot. 2008, 22, 3–20.

- Hecht, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Gácsi, M. Behavioral assessment and owner perceptions of behaviors associated with guilt in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 139, 134–142.

- Vollmer, P.J. Do mischievous dogs reveal their “guilt”? Vet. Med. Small Anim. Clin. 1977, 72, 1002–1005.

- Horowitz, A. Disambiguating the “guilty look”: Salient prompts to a familiar dog behaviour. Behav. Process. 2009, 81, 447–452.

- Rajecki, D.; Rasmussen, J.L.; Sanders, C.R.; Modlin, S.J.; Holder, A.M. Good Dog: Aspects of humans’ causal attributions for a companion animal’s ocial behavior. Soc. Anim. 1999, 7, 17–34.

- Mariti, C.; Ricci, E.; Zilocchi, M.; Gazzano, A. Owners as a secure base for their dogs. Behaviour 2013, 150, 1275–1294.

- Solomon, J.; Beetz, A.; Schöberl, I.; Gee, N.; Kotrschal, K. Attachment security in companion dogs: Adaptation of Ainsworth’s strange situation and classification procedures to dogs and their human caregivers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2019, 21, 389–417.

- Riggio, G. A mini review on the dog-owner attachment bond and its implications in veterinary clinical ethology. Dog. Behav. 2020, 6, 17–26.

- Riggio, G.; Gazzano, A.; Zsilák, B.; Carlone, B.; Mariti, C. Quantitative behavioral analysis and qualitative classification of attachment styles in comestic dogs: Are dogs with a secure and an Insecure-Avoidant attachment different? Animals 2020, 11, 14.

- Muris, P.; Mayer, B.; Meesters, C. Self-reported attachment style, anxiety, and depression in children. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2000, 28, 157–162.

- Schimmenti, A.; Bifulco, A. Linking lack of care in childhood to anxiety disorders in emerging adulthood: The role of attachment styles. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2015, 20, 41–48.

- Spruit, A.; Goos, L.; Weenink, N.; Rodenburg, R.; Niemeyer, H.; Stams, G.J.; Colonnesi, C. The relation between attachment and depression in children and adolescents: A multilevel meta-analysis. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 23, 54–69.

- Manicavasagar, V.; Silove, D.; Marnane, C.; Wagner, R. Adult attachment styles in panic disorder with and without comorbid adult separation anxiety disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2009, 43, 167–172.

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. Attachment, anger, and aggression. In Human Aggression and Violence: Causes, Manifestations, and Consequences; Shaver, P.R., Mikulincer, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 241–257.

- van Leeuwen, W.A.; van Wingen, G.A.; Luyten, P.; Denys, D.; van Marle, H.J.F. Attachment in OCD: A meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 70, 102187.

- Landsberg, G.; Hunthausen, W.; Ackerman, L. Behavior Problems of the Dog and Cat, 3rd ed.; Saunders Elsevier: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2011; pp. 1–454.

- Cavalcanti, A.L.; Porto, E.; dos Santos, B.F.; Cavalcanti, C.L.; Cavalcanti, A.F.C. Facial dog bite injuries in children: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 41, 57–60.

- Meints, K.; Brelsford, V.; De Keuster, T. Teaching children and parents to understand dog signaling. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 1–13.

- Chapman, S.; Cornwall, J.; Righetti, J.; Sung, L. Preventing dog bites in children: Randomised controlled trial of an educational intervention. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2000, 320, 1512–571513.

- Wilson, F.; Dwyer, F.; Bennett, P.C. Prevention of dog bites: Evaluation of a brief educational intervention program for preschool children. J. Community Psychol. 2003, 31, 75–86.

- De Keuster, T.; Lamoureux, J.; Kahn, A. Epidemiology of dog bites: A Belgian experience of canine behaviour and public health concerns. Vet. J. 2006, 172, 482–487.

- Serpell, J. Anthropomorphism and Anthropomorphic Selection—Beyond the ‘Cute Response’. Soc. Anim. 2002, 10, 437–454.

- Steinert, K.; Kuhne, F.; Kramer, M.; Hackbarth, H. People’s perception of brachycephalic breeds and breed-related welfare problems in Germany. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 33, 96–102.

- Aromaa, M.; Lilja-Maula, L.; Rajamäki, M. Assessment of welfare and brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome signs in young, breeding age French Bulldogs and Pugs, using owner questionnaire, physical examination and walk tests. Anim. Welf 2019, 28, 287–298.

- Bartels, A.; Martin, V.; Bidoli, E.; Steigmeier-Raith, S.; Brühschwein, A.; Reese, S.; Köstlin, R.; Erhard, M. Brachycephalic problems of pugs relevant to animal welfare. Anim. Welf 2015, 24, 327–333.

- Schatz, K.Z.; Engelke, E.; Pfarrer, C. Comparative morphometric study of the mimic facial muscles of brachycephalic and dolichocephalic dogs. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2021, 50, 863–875.

- Chorpita, B.F.; Barlow, D.H. The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 3–21.

- Harrison, M.A.; Hall, A.E. Anthropomorphism, empathy, and perceived communicative ability vary with phylogenetic relatedness to humans. J. Soc. Evol. Cult. Psychol. 2010, 4, 34–48.

- Chan, A.A.Y.-H. Anthropomorphism as a conservation tool. Biodivers. Conserv. 2012, 21, 1889–1892.

- Morton, D.B.; Berghardt, G.M.; Smith, J.A. Critical anthropomorphism, animal suffering, and the ecological context. Hastings Cent. Rep. 1990, 20, S13.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

10.8K

Entry Collection:

Environmental Sciences

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

05 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No