Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Erika V S Albuquerque | + 1780 word(s) | 1780 | 2021-12-20 03:21:47 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | Meta information modification | 1780 | 2021-12-22 02:02:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Albuquerque, E. Coffee Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17403 (accessed on 12 January 2026).

Albuquerque E. Coffee Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17403. Accessed January 12, 2026.

Albuquerque, Erika. "Coffee Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17403 (accessed January 12, 2026).

Albuquerque, E. (2021, December 21). Coffee Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17403

Albuquerque, Erika. "Coffee Leaf Miner Leucoptera coffeella." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 December, 2021.

Copy Citation

The coffee leaf miner (CLM) Leucoptera coffeella moth is a major threat to coffee production. Insect damage is related to the feeding behavior of the larvae on the leaf. During the immature life stages, the insect feeds in the mesophyll triggering necrosis and causing loss of photosynthetic capacity, defoliation and significant yield loss to coffee crops. Chemical control is used to support the coffee production chain, though market requirements move toward conscious consumption claiming for more sustainable methods.

resistance

cultivar

biopesticide

biological control

chemical control

life cycle

CLM

1. Introduction

Since the VI century, coffee consumption has expanded from goats to human beings and has been increasingly gaining followers. Its stakeholders operate not only in planting, harvesting, roasting, packaging, transporting, and blending, but also in wholesale and retail marketing ranging from modest diners to sophisticated restaurants and high-profile tasting contests. Although coffee is a non-essential food commodity, its commercial chain is one of the most profitable and complex in the world with the 2020/21 yield estimated at 176.1 million bags [1], produced in several countries, such as Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia, Indonesia among others [1][2]. Brazil is currently the largest producer and exporter, with a record expectation of 67 million bags of processed coffee [1], where few states account for more than 90% of national production [3].

The challenges for maintaining this productive chain are many, among which are the pests that threaten the crop, including some of the phytophagous organisms as leaf miner Leucoptera coffeella (Guérin-Mèneville and Perrottet) (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae), a coffee exclusive enemy [4], the coffee berry borer Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Scolitidae), several species of cochineal (coccids, pseudococcids, and diaspidids) and cicadas (Hemiptera), and mites (Acari).

The coffee leaf miner (CLM) (L. coffeella), is considered one of the most important coffee pests due to the high damage this moth causes to coffee plantations. The damage is a result of injuries caused by its larvae that feed on the palisade parenchyma of the coffee leaves, which consequently reduces fruit production [5]. Estimated losses in neotropical producing countries can reach up to 87% of the coffee productivity, depending on the season, the defoliation can reach up to 75% [6][7]. High infestation rates of L. coffeella can cause losses above 50% in Brazil and Colombia [8][9][10][11], vary from 20% to 40% in Puerto Rico and around 12% in Mexico [12][13]. The CLM incidence surveys are flawed because the monitoring is done by sampling mined leaves or traps and this system is not ideal. New systems employing aerial images and terrestrial photogrammetry are being developed to facilitate its detection in the field [14][15].

Consumer expansion in new markets has led coffee growers to search for sustainable production systems, like adoption of lower environmental impact agricultural practices leading to greater economic value of the product [16][17][18]. The selection of resistant populations has been reported for most of the insecticides currently used in preventive approaches [11]. Although important as a natural mortality factor, biological control agents are not efficient when used as a stand-alone strategy. Therefore, biotechnological strategies can generate alternatives to meet the demand for sustainable, durable, and safe solutions for specific CLM control. In addition, currently, to access more demanding markets, farmers must use methods consistent with the integrated pest management (IPM) philosophy, and not just chemical control methods [19][20][21].

2. History, Origin, and Distribution

Despite its origin in the African continent, CLM was first reported 178 years ago in coffee plantations in the Caribbean Antilles [22][23][24]. It was first named Elachista coffeella, then assigned to Bucculatrix sp. (Stainton, 1858) and later in Cemiostoma sp. (Stainton, 1861). Finally, it was included in the genus Leucoptera (Meyrick, 1895) and named L. coffeella in 1897 by Lord Walsingham. It was already reported as Perileucoptera coffeella, synonymous [25].

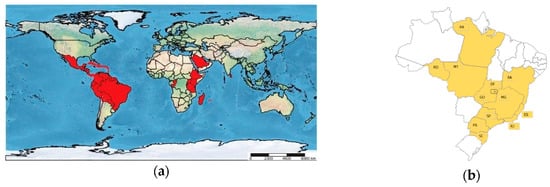

L. coffeella is now a cosmopolitan pest (Figure 1a) and occurs in the leaves of coffee plants in Africa, Asia, and Neotropical countries, comprising Central America, the Caribbean islands, and South America [23][26][27][28]. In Brazil, the presence of CLM was detected around the 19th century and became a key pest of coffee culture in the country [29]. Since then, wherever coffee is grown, the CLM is present [30][31][32] (Figure 1b) specially in the Brazilian Savanna Biome called Cerrado.

Figure 1. Presence of L. coffeella in: (a) The world map, showing producing countries highlighted in red: North and Central America: Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico, Montserrat, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago; South America: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela; Africa: Reunion, Mauritius, Madagascar, Uganda, Kenya, Congo, Ethiopia, Tanzania and Rwanda; Asia: Saudi Arabia and Sri Lanka, and (b) Brazil, highlighting in yellow the affected producing states: RO = Rondônia, MT = Mato Grosso, PA = Pará, GO = Goiás, DF = Distrito Federal, BA = Bahia, MG = Minas Gerais, ES = Espírito Santo, SP = São Paulo, RJ = Rio de Janeiro, PR = Paraná, SC = Santa Catarina.

3. Biology

3.1. Life Cycle

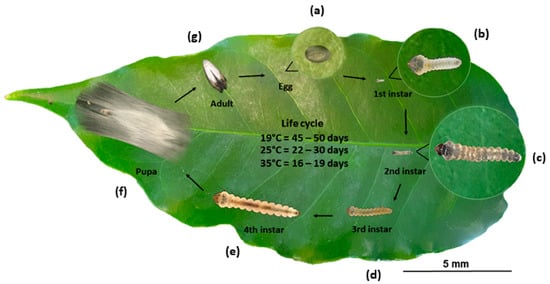

The CLM is a holometabolous insect, its life cycle includes different stages [33][34] (Figure 2). Considering a 25 °C temperature, the egg stage usually lasts about five days, the larval stage lasts about twelve days, and the pupae lasts about five days, totaling approximately 22 days until reaching adulthood [35]. Total life cycle varies according to temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall. In the dry season, the attack of the pest is generally more severe than in wet periods [36][37].

Figure 2. L. coffeella life stages from egg to adult. After hatching the egg, (a) the larvae development is divided into four instars: L1 (b), L2 (c), L3 (d), and L4 (e). The last instar forms a cocoon and turns into pupa (f). The adult emerges (g) from the pupa to mate. Eggs are laid over the adaxial side of the coffee leaf and the cycle restarts. Temperature rising accelerates and shortens the cycle span time, as detailed.

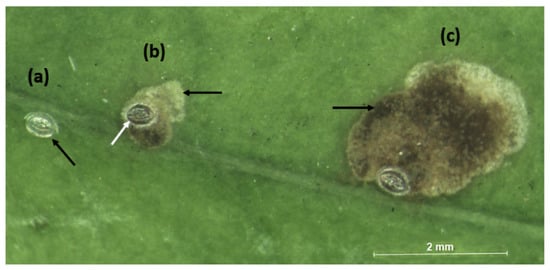

The egg is about 0.3 mm, made by a translucent structure, with an oval, concave shape, and expanded sides [23][36]. After hatching, the larvae leave the underside of the eggs, which are in contact with the upper leaf epidermis, and get into the leaves [38] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. L. coffeella egg hatching and mine progression: (a) Unhatched eggs have a translucent structure, the arrow indicates a freshly oviposited egg; (b) after hatching, the eggshell becomes darker (white arrow) and the larva penetrates the leaf under the egg and starts feeding, forming a light green mine (black arrow); (c) enlargement of the mine. The black arrow indicates the dark color of the mine due to residues left behind by the larva.

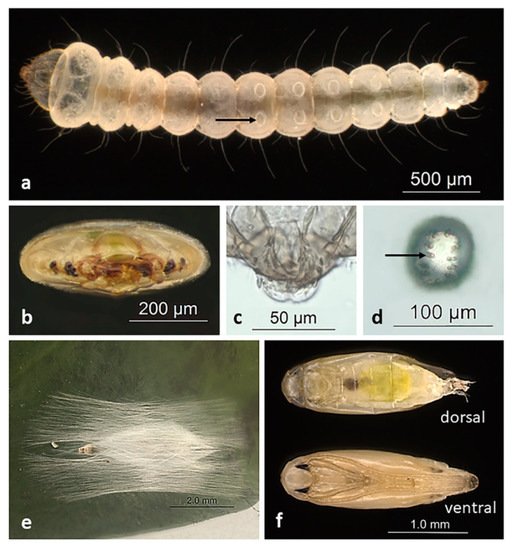

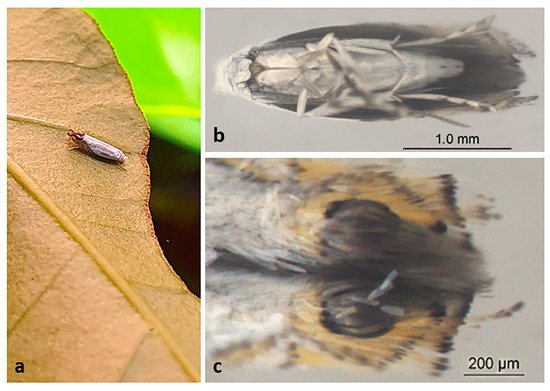

The L. coffeella larval phase has four instars [34][39]. Newly hatched larvae have a translucent whitish color, but throughout their development they take on a greenish yellow tone. The last larval instar is about 4–5 mm, flattened, segmented with 11 segments, and yellowish in color [22][23] (Figure 4a). Fourth instar larvae have a flat head and mouthpiece of the chewing type (Figure 4b,c), prolegs, and crochets [23][34][40] (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. Immature stages of L. coffeella. (a) Ventral view of a fourth instar larva. Arrow indicates proleg; (b) flat head in front view; (c) chewing mouthpiece; (d) crochets (arrow) located in proleg. Morphology details to distinguish the immature stages are described in the text; (e) pupa’s sea cocoon; (f) pupae’s dorsal (a), and ventral (b) shapes.

After accomplishing the larval stages, the larvae leave the mines and weave a silk X-shaped cocoon, usually in the axial region of the leaf, forming the pupae [23][36] (Figure 4e). Pupae have an approximate length of 2 mm, milky color, small black eyes, antennas, and legs ventrally fused, and wrinkled wings [23] (Figure 4f). Usually, more pupae are found in the “skirt” region of coffee plants, which is the underside of the plant where dead leaves accumulate [38].

From the pupae, adults emerge with an average body length of 2 mm and a wingspan of 6.5 mm (Figure 5a). They have a head with “white hair scales”, long antennae that reach the end of the abdomen, silver white chest, legs covered with white bristles, wing with three rows of yellow bristles at the apex with a black circle, yellowish abdomen and covered with white scales and genital organs covered by a tuft of white scales [22][23] (Figure 5b,c). A recent description of the sexual polymorphism [34] shows the differentiation of the structures present in both male and female genitalia: male—bulbus ejaculatorius, valve, gnathos, and aedeagus and female—ovipositor, sclerite, and corpus bursae. Overall, the female whole body is similar to the male, except by a slightly longer average length.

Figure 5. L. coffeella adults (a) perched on coffee leaf; (b) male seen by ventral view, with white scales all over the body; (c) closed caption of the wings apex from dorsal view to show details: black circle surrounded by yellow bristles.

3.2. Larval Feeding Behavior

CLM is a monophagous pest, coffee exclusive and the larvae are the causal agent of the crop damage [4]. When feeding on the mesophyll of the coffee tree leaves, the insect creates mines that justify the common name of the pest—coffee leaf miner (Figure 6a). The mines cause necrosis (Figure 6b) and reduce the photosynthetic leaf surface (Figure 6c,d), leading to a lower photosynthetic rate of the plants and consequent depletion of the plant and productivity diminish [33]. The damage caused by this insect includes defoliation [36] (Figure 6e). Eventually, without adequate cultural treatments, the infestation can lead to the death of the plant.

Figure 6. Damage to coffee leaf caused by the CLM larvae. (a) Initial mine formation; (b) mine developed, with large necrotic area; (c) larvae inside the mine; (d) leaf with impaired photosynthetic surface; (e) coffee defoliation.

A relationship between the feeding damage of CLM and the application of synthetic fertilizers has been described in the literature [41][42]. The amount of free amino acids and reducing sugars in the metabolic system of coffee plants is related to nutritional imbalance and susceptibility to pests. Plants fertilized with organic material showed a decrease of up to 50% of leaf mines [41].

3.3. Adult Behavior

L. coffeella is depicted as the quintessence of sensitivity level [37]. In adulthood, the insect has a nocturnal habit and during the day, it shelters beneath the coffee leaves [36]. Mating and laying occur preferably at night [38][39][43]. The sexual behavior of adults is very peculiar and can present the following stages: (1) Females remain in a resting position with the abdomen curved downwards, exposing the pheromone gland in continuous movements from the inside out, to attract males; (2) when perceiving the pheromone, males remain in the same place, moving their antennae and flapping their wings, and then walk toward the female; (3) male touches the female with his antennae, female retracts the pheromone gland and places the abdomen toward the male; (4) the male places his abdomen toward the female abdomen, releases the aedeagus and fits the female, initiating copulation [44]. Females usually oviposit in the upper epidermis of the leaves at nightfall [36][38].

References

- USDA. Coffee: World Markets and Trade; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Souza, B.; Vázquez, L.L.; Marucci, R.C. Natural Enemies of Insect Pests in Neotropical Agroecosystems: Biological Control and Functional Biodiversity; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-24733-1.

- CONAB. Acompanhamento Da Safra Brasileira de Café. Prim. Levant. 2021, 8, 72.

- Rena, A.B.; Malavolta, E.; Rocha, M.; Yamada, T. Cultura Do Cafeeiro—Fatores Que Afetam a Produtividade; Associacao Brasileira para Pesquisa da Potassa e do Fosfato: Piracicaba, Brazil, 1986; p. 447.

- Parra, J.R.P.; Reis, P.R. Manejo integrado para as principais pragas da cafeicultura, no Brasil. Visão Agríc. 2013, 8, 47–50.

- Neves, M.F. Análise Dos Benefícios Econômicos e Sociais Da Utilização Do Carbofurano No Controle de Nematoides, Bicho Mineiro (Leucoptera coffeella) e Cigarra Do Cafeeiro (Quesada Gigas e Fidicina Pronoe) Na Cultura Do Café. Univ. Sao Paulo 2016, 29, 1–29.

- de Souza, J.C.; Reis, P.R.; de Oliveira, R.L.; Ciociola Júnior, A.I. Eficiência de Thiamethoxam No Controle do Bicho-Mineiro do Cafeeiro. II—Influência na Época de Aplicação via Irrigação por Gotejamento; SBICafé: Viçosa, Brazil, 2006.

- Ramiro Alves, D.; Filho-Guerreiro, O.; Voltan-Queiroz, R.B.; Matthiesen Chebabi, S. Caracterização anatômica de folhas de cafeeiros resistentes e suscetíveis ao bicho-mineiro. Bragantia 2004, 63, 363–372.

- Constantino, L.M.; Flórez, J.C.; Benavides, P.; Bacca, R. Minador de las Hojas del Cafeto: Una Plaga Potencial por Efectos del Cambio Climático; Centro Nacional de Investigaciones de Café (Cenicafé): Caldas, Colômbia, 2013.

- David-Rueda, G.; Constantino, L.M.; Montoya, E.C.; Ortega, M.O.E.; Gil, Z.N.; Benavides-Machado, P. Diagnóstico de Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae) y Sus Parasitoides En El Departamento de Antioquia, Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Entomol. 2016, 42, 4–11.

- Leite, S.A.; dos Santos, M.P.; da Costa, D.R.; Moreira, A.A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Castellani, M.A. Time-Concentration Interplay in Insecticide Resistance among Populations of the Neotropical Coffee Leaf Miner, Leucoptera coffeella. Agric. For. Entomol. 2021, 23, 232–241.

- Giraldo, J.M.; Postali, P.J.R. Biological Aspects of Leucoptera coffeella Guerin Meneville 1842 Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae in Coffea Arabica under Laboratory Conditions; Cenicafé: Chinchiná, Colombia, 2017; pp. 20–27.

- Vega, F.; Posada-Florez, F.; Infante, F. Coffee Insects: Ecology and Control. In Encyclopedia of Pest Managment; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2006; pp. 1–4.

- Souto, L.A. Ocorrência de Leucoptera coffeella e Detecção Da Presença de Minas Comparando Amostragem Convencional e Amostragem Por Fotogrametria Terrestre; Repositório Institucional, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia—Instituto de Ciências Agrárias (ICIAG): Uberlândia, Brazil, 2019; p. 27.

- Vasconcelos, G.C. Identificação da praga bicho-mineiro em plantações de café usando imagens aéreas e deep learning. Univ. Uberlandia 2019, 30, 1–30.

- Leite, S.A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; dos Santos, M.P.; da Costa, D.R.; Moreira, A.A.; Matsumoto, S.N.; Lemos, O.L.; Castellani, M.A. Profile of Coffee Crops and Management of the Neotropical Coffee Leaf Miner, Leucoptera coffeella. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8011.

- da Consolação Rosado, M.; de Araújo, G.J.; Pallini, A.; Venzon, M. Cover Crop Intercropping Increases Biological Control in Coffee Crops. Biol. Control 2021, 160, 104675.

- Valerio, D.R.; Jiménez, F.G. Manejo del minador de la hoja (Leucoptera coffeella) en el cultivo de café en Costa Rica. Agron. Costarric. Rev. Cienc. Agríc. 2021, 45, 143–153.

- Guastella, D.; Massimino Cocuzza, G.E.; Rapisarda, C. Integrated Pest Management. In Integrated Pest Management in Tropical Regions; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 285–312.

- Świtek, S.; Sawinska, Z. Farmer Rationality and the Adoption of Greening Practices in Poland. Sci. Agric. 2017, 74, 275–284.

- Sawinska, Z.; Świtek, S.; Głowicka-Wołoszyn, R.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł. Agricultural Practice in Poland Before and After Mandatory IPM Implementation by the European Union. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1107.

- Guérin-Méneville, F.-É.; Perrottet, S. Mémoire sur un Insecte et un Champignon qui Ravagent les Cafiers aux Antilles; Bouchard-Huzard: Paris, France, 1842; pp. 6–30.

- Box, H.E. The Bionomics of the White Coffee-Leaf Miner, Leucoptera coffeella, Guér., in Kenya Colony. (Lepidoptera, Lyonetidae.). Bull. Entomol. Res. 1923, 14, 133–145.

- Gallo, D.O.; Nakano, S.S.; Neto, R.P.L.; Carvalho, G.C.; Batista, E.B.; Filho, J.R.P.; Parra, R.A.; Zucchi, S.B.; Alves, J.D. Vendramim Manual de Entomologia AgrÌcola; Agronômica Ceres: Ouro Fino, Brazil, 1988; p. 649.

- Silvestri, F. Compendio di Entomologica Applicata (Agraria, Forestale, Medica, Veterinaria); Bellavista: Portici, Italy, 1943; p. 512.

- Green, G. A Proposed Origin of the Coffee Leaf-Miner, Leucoptera coffeella (Guerin-Meneville) (Lepidoptera:Lyonetiidae). Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1984, 30, 30–31.

- Mey, W. Taxonomische Bearbeitung Der Westpaläarktischen Arten Der Gattung Leucoptera Hübner, ‘1825′, s. 1. (Lepidoptera, Lyonetiidae) ‘Taxonomic Revision of the Westpalaearctic Species of the Genus Leucoptera Hübner, “1825”, s. I. (Lepidoptera, Lyonetiidae)’. Dtsch. Entomol. Z. 1994, 41, 173–234.

- Pereira, E.J.G.; Picanço, M.C.; Bacci, L.; Lucia, T.M.C.D.; Silva, É.M.; Fernandes, F.L. Natural Mortality Factors of Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae) on Coffea Arabica. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2007, 17, 441–455.

- Medina Filho, H.P.; Carvalho, A.; Mônaco, L.C. Melhoramento do cafeeiro: XXXVII—Observações sobre a resistência do cafeeiro ao bicho-mineiro. Bragantia 1977, 36, 131–137.

- Ghini, R.; Hamada, E.; Pedro Júnior, M.J.; Marengo, J.A.; Gonçalves, R.R.D.V. Risk Analysis of Climate Change on Coffee Nematodes and Leaf Miner in Brazil. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2008, 43, 187–194.

- Pantoja-Gomez, L.M.; Corrêa, A.S.; de Oliveira, L.O.; Guedes, R.N.C. Common Origin of Brazilian and Colombian Populations of the Neotropical Coffee Leaf Miner, Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 924–931.

- Parra, J.R.P.; Gonçalves, W.; Precetti, A.A.C.M. Flutuação Populacional de Parasitos e Predadores de Perileucoptera coffeella (Guérin-Méneville, 1842) Em Três Localidades Do Estado de São Paulo. Turrialba 1981, 31, 357–364.

- de Souza, J.C.; Reis, P.R.; Rigitano, R.D.O. Bicho-Mineiro Do Cafeeiro: Biologia, Danos e Manejo Integrado; EPAMIG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 1998; pp. 48–54.

- Motta, I.O.; Dantas, J.; Vidal, L.; Bílio, J.; Pujol-Luz, J.R.; Albuquerque, É.V.S. The Coffee Leaf Miner, Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae): Identification of the Larval Instars and Description of Male and Female Genitalia. Rev. Bras. Entomol. 2021, 65, e20200122.

- Katiyar, K.P.; Ferrer, F. Rearing Technique, Biology and Sterilization of the Coffee Leaf Miner, Leucoptera coffeella Guer. (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae); International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 1968; pp. 165–175.

- Costa, J.N.M.; Teixeira, C.A.D.; Júnior, J.R.V.; Rocha, R.B.; de Freitas Fernandes, C. Informações para facilitar a identificação das diferentes fases do bicho-mineiro (Leucoptera coffeella) em campo. Embrapa Rondônia-Comun. Técnico INFOTECA-E 2012, 4, 1–4.

- Wolcott, G.N. A Quintessence of Sensitivity: The Coffee Leaf-Miner. J. Agric. Univ. Puerto Rico 1947, 31, 215–219.

- Guerreiro Filho, O. Coffee Leaf Miner Resistance. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 109–117.

- Notley, F.B. The Leucoptera Leaf Miners of Coffee on Kilimanjaro; Leucoptera coffeella, Guér. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1948, 39, 399–416.

- Nielsen, C.D. The Insects of Australia: A Textbook for Students and Research Workers; Melbourne University Press: Carlton, VIC, Australia, 1991; ISBN 978-0-522-84454-2.

- de Sabino, P.H.; Junior, F.A.R.; Carvalho, G.A.; Mantovani, J.R. Nitrogen Fertilizers and Occurence of Leucoptera coffeella (Guérin-Mèneville & Perrottet) in Transplanted Coffee Seedlings. Coffee Sci. Braz. 2018, 13, 410–414.

- De Almeida, V.C.; Guimarães, R.J.; Mendes, A.N.G. Infestação por bicho-mineiro e teores foliares de açúcares solúveis totais e proteína em cafeeiros orgânicos. Coffee Sci. 2014, 9, 300–311.

- Conceição, C.H.C.; Guerreiro-Filho, O.; Gonçalves, W. Flutuação populacional do bicho-mineiro em cultivares de café arábica resistentes à ferrugem. Bragantia 2005, 64, 625–631.

- Michereff, M.F.F.; Michereff, M.; Vilela, E.F. Mating Behavior of the Coffee Leaf-Miner Leucoptera coffeella (Guerin-Meneville) (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2007, 36, 376–382.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agronomy

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

4.1K

Entry Collection:

Environmental Sciences

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

22 Dec 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No