| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anca Panaitescu | + 1813 word(s) | 1813 | 2021-12-08 19:14:53 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1813 | 2021-12-17 03:24:33 | | |

Video Upload Options

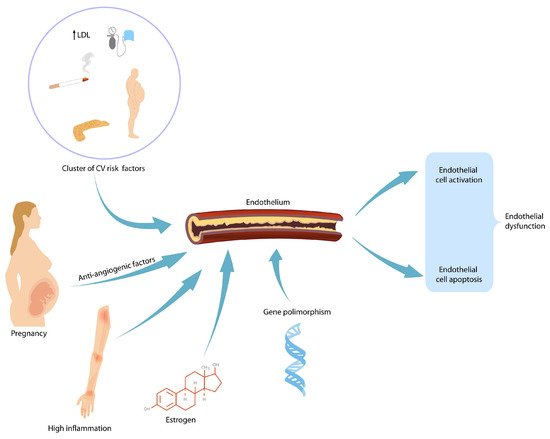

During gestation, the maternal body should increase its activity to fulfil the demands of the developing fetus as pregnancy progresses. Each maternal organ adapts in a unique manner and pace. In an organ or system that was already vulnerable before pregnancy, the burden of pregnancy can trigger overt clinical manifestations. After delivery, symptoms usually reside; however, in time, because of the age-related metabolic and pro-atherogenic changes, they reappear. Therefore, it is believed that pregnancy acts as a medical stress test for mothers. Pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus foreshadow cardiovascular disease and/or diabetes later in life. Affected women are encouraged to modify their lifestyle after birth by adjusting their diet and exercise habits. Blood pressure and plasmatic glucose level checking are recommended so that early therapeutic intervention can reduce long-term morbidity.

1. Preeclampsia and Future Cardiovascular Risks for Mothers

2. Preeclampsia and Future Renal Disease in Mothers

3. Gestational Hypertension and Future Cardiovascular Risks for Mothers

4. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

5. Thrombosis during Pregnancy

6. Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy

References

- Magnussen, E.B.; Vatten, L.J.; Lund-Nilsen, T.I.; Salvesen, K.A.; Davey Smith, G.; Romundstad, P.R. Prepregnancy cardiovascular risk factors as predictors of preeclampsia: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2007, 335, 978.

- Ray, J.G.; Diamond, P.; Singh, G.; Bell, C.M. Brief overview of maternal triglycerides as risk factor for pre-eclampsia. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2006, 113, 379–386.

- Chappell, L.C.; Enye, S.; Seed, P.; Briley, A.L.; Poston, L.; Shennan, A.H. Adverse perinatal outcomes and risk factors for preeclampsia in women with chronic hypertension: A prospective study. Hypertension 2008, 51, 1002–1009.

- Innes, K.E.; Wimsatt, J.H.; McDuffie, R. Relative glucose tolerance and subsequent development of hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 905–910.

- Mello, G.; Parretti, E.; Marozio, L.; Pizzi, C.; Lojacono, A.; Frusca, T.; Facchinetti, F.; Benedetto, C. Thrombophilia is significantly associated with severe preeclampsia: Results of a large-scale, case controlled study. Hypertension 2005, 46, 1270–1274.

- Burton, G.J.; Woods, A.W.; Jauniaux, E.; Kingdom, J.C. Heological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta 2009, 30, 473–482.

- Levine, R.J.; Lam, C.; Qian, C.; Yu, K.F.; Maynard, S.E.; Sachs, B.P.; Sibai, B.M.; Epstein, F.H.; Romero, R.; Thadhani, R.; et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 992–1005.

- Levine, R.J.; Qian, C.; Maynard, S.E.; Kai, F.Y.; Epstein, F.H.; Karumanchi, S.A. Serum sFlt-1 concentration during preeclampsia and mid-trimester blood pressure in healthy nulliparous women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1034–1041.

- Rolnik, D.L.; Wright, D.; Syngelaki, A.; Nicolaides, K.; Poon, L.C.Y.; O’Gorman, N.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Akolekar, R.; Cicero, S.; Janga, D.; et al. ASPRE trial: Performance of screening for preterm pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 50, 492–495.

- Panaitescu, A.M.; Roberge, S.; Nicolaides, K.H. Chronic hypertension: Effect of blood pressure control on pregnancy outcome. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017, 32, 857–863.

- McDonald, S.D.; Malinowski, A.; Zhou, Q.; Yusuf, S.; Devereaux, P.J. Cardiovascular sequleae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Am. Heart J. 2008, 156, 918–930.

- Thilaganathan, B.; Kalafat, E. Cardiovascular system in preeclampsia and beyond. Hypertension 2019, 73, 522–531.

- Melchiorre, K.; Thilaganathan, B.; Giorgione, V.; Ridder, A.; Memmo, A.; Khalil, A. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and future cardiovascular health frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 1–16.

- Grand’Maison, S.; Pilote, L.; Schlosser, K.; Stewart, D.J.; Okano, M.; Dayan, N. Clinical features and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome in women with previous pregnancy complications. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 1683–1692.

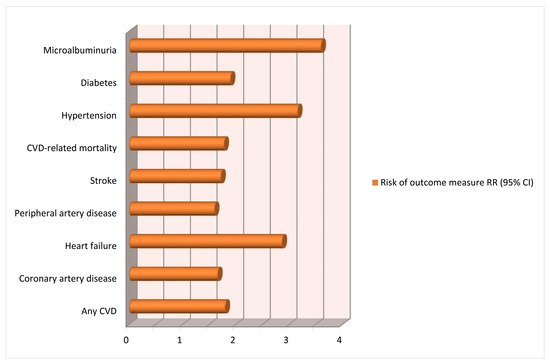

- Bellamy, L.; Casas, J.P.; Hingorani, A.D.; Williams, D.J. Preeclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007, 335, 974–977.

- Theilen, L.H.; Meeks, H.; Fraser, A.; Esplin, M.S.; Smith, K.R.; Varner, M.W. Long-term mortality risk and life expectancy following recurrent hypertensive disease of pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 219, 1–11.

- Brouwers, L.; van der Meiden-van Roest, A.J.; Savelkoul, C.; Vogelvang, T.E.; Lely, A.T.; Franx, A.; van Rijn, B.B. Recurrence of pre-eclampsia and the risk of future hypertension and cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG 2018, 125, 1642–1654.

- Chen, S.N.; Cheng, C.C.; Tsui, K.H.; Tang, P.L.; Chern, C.U.; Huang, W.C.; Lin, L.T. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and future heart failure risk: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018, 13, 110–115.

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corrà, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2315–2381.

- Bokslag, A.; Franssen, C.; Alma, L.J.; Kovacevic, I.; Van Kesteren, F.; Teunissen, P.W.; Kamp, O.; Ganzevoort, W.; Hordijk, P.L.; De Groot, C.J.M.; et al. Early-onset preeclampsia predisposes to preclinical diastolic left ventricular dysfunction in the fifth decade of life: An observational study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198908.

- Alma, L.J.; Bokslag, A.; Maas, A.H.E.M.; Franx, A.; Paulus, W.J.; de Groot, C.J.M. Shared biomarkers between female diastolic heart failure and pre-eclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ESC Heart Fail. 2017, 4, 88–98.

- Kirollos, S.; Skilton, M.; Patel, S.; Arnott, C. A systematic review of vascular structure and function in pre-eclampsia: Non-invasive assessment and mechanistic links. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 1–12.

- Brown, N.; Khan, F.; Alshaikh, B.; Berka, N.; Liacini, A.; Alawad, E.; Yusuf, K. CD-34 + and VE-cadherin + endothelial progenitor cells in preeclampsia and normotensive pregnancies. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2019, 16, 42–47.

- Wua, R.; Wanga, T.; Gu, R.; Xing, D.; Ye, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and risk of cardiovascular disease-related morbidity and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiology 2020, 145, 633–647.

- Lafayette, R.A. The kidney in preeclampsia. Kidney Int. 2005, 67, 1194–1203.

- Hussein, W.; Lafayette, R.A. Renal function in normal and disordered pregnancy. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2014, 23, 46–53.

- McDonald, S.D.; Han, Z.; Walsh, M.W.; Gerstein, H.C.; Devereaux, P.J. Kidney disease after preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 55, 1026–1039.

- Vikse, B.E.; Irgenss, L.M.; Leivestad, T.; Skjaerven, R.; Iversen, B.M. Preeclampsia and the risk of end-stage renal disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 800–809.

- Männistö, T.; Mendola, P.; Vääräsmäki, M.; Järvelin, M.R.; Hartikainen, A.L.; Pouta, A.; Suvanto, E. Elevated blood pressure in pregnancy and subsequent chronic disease risk. Circulation 2013, 12, 681–690.

- Ray, J.G.; Vermeulen, M.J.; Schull, M.J.; Redelmeier, D.A. Cardiovascular health after maternal placental syndromes (CHAMPS): Population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2005, 366, 1797–1803.

- Garovic, V.D.; White, M.W.; Vaughan, L.; Saiki, M.; Parashuram, S.; Garcia-Valencia, O.; Weissgerber, T.L.; Milic, N.; Weaver, A.; Mielke, M.M. Incidence and long-term outcomes of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 18, 2323–2334.

- Kjos, S.L.; Buchanan, T.A. Gestational diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 749–756.

- Panaitescu, A.M.; Peletcu, G. Gestational diabetes. Obstetrical perspective. Acta Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 331–334.

- Bellamy, L.; Casas, J.P.; Hingorani, A.D.; Williams, D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 1773–1779.

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190; ACOG: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Ehrlich, S.F.; Hedderson, M.M.; Quesenberry, C.P.J.; Feng, J.; Brown, S.D.; Crites, Y.; Ferrara, A. Post-partum weight loss and glucose metabolism in women with gestational diabetes:the DEBI Study. Diabet. Med. 2014, 31, 862–867.

- Bentley-Lewis, R.; Levkoff, S.; Stuebe, A.; Seely, E.W. Gestational diabetes mellitus: Postpartum opportunities for the diagnosis and prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 4, 552–558.

- Carr, D.B.; Utzschneider, K.M.; Hull, R.L.; Tong, J.; Wallace, T.M.; Kodama, K.; Shofer, J.B.; Heckbert, S.R.; Boyko, E.J.; Fujimoto, W.Y.; et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus increases the risk of cardiovascular disease in women with a family history of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 2078–2083.

- Kramer, C.K.; Campbell, S.; Retnakaran, R. Gestational diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 905–914.

- Mosca, L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Berra, K.; Bezanson, J.L.; Dolor, R.J.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Newby, L.K.; Piña, I.L.; Roger, V.L.; Shaw, L.J.; et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women–2011 update: A guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011, 123, 1243–1262.

- Bomback, A.S.; Rekhtman, Y.; Whaley-Connell, A.T.; Kshirsagar, A.V.; Sowers, J.R.; Chen, S.C.; Li, S.; Chinnaiyan, K.M.; Bakris, G.L.; McCullough, P.A. Gestational diabetes mellitus alone in the absence of subsequent diabetes is associated with microalbuminuria: Results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 2586–2591.

- Rawal, S.; Olsen, S.F.; Grunnet, L.G.; Ma, R.C.; Hinkle, S.N.; Granström, C.; Wu, J.; Yeung, E.; Mills, J.L.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and renal function: A prospective study with 9- to 16-year follow-up after pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1378–1384.

- Greer, I.A. Thrombosis in pregnancy: Maternal and fetal issues. Lancet 1999, 10, 1258–1265.

- Wik, H.S.; Jacobsen, A.F.; Sandset, P.M. Long-term outcome after pregnancy-related venous thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135 (Suppl. 1), S1–S4.

- Walker, I.D. Prothrombotic genotypes and pre-eclampsia. Thromb. Haemost. 2002, 87, 777–778.

- Lazarus, J.H. Epidemiology and prevention of thyroid disease in pregnancy. Thyroid 2002, 12, 861–865.

- Strieder, T.G.; Prummel, M.F.; Tijssen, J.G.; Endert, E.; Wiersinga, W.M. Risk factors for and prevalence of thyroid disorders in a cross-sectional study among healthy female relatives of patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Clin. Endocrinol. 2003, 59, 396–401.

- Premawardhana, L.D.; Parkes, A.B.; Ammari, F.; John, R.; Darke, C.; Adams, H.; Lazarus, J.H. Postpartum thyroiditis and long-term thyroid status: Prognostic influence of thyroid peroxidase antibodies and ultrasound echogenicity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 71–75.

- Lazarus, J.H.; Ammari, F.; Oretti, R.; Parkes, A.B.; Richards, C.J.; Harris, B. Clinical aspects of recurrent postpartum thyroiditis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 1997, 47, 305–308.

- Stagnaro-Green, A.; Schwartz, A.; Gismondi, R.; Tinelli, A.; Mangieri, T.; Negro, R. High rate of persistent hypothyroidism in a large-scale prospective study of postpartum thyroiditis in southern Italy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 652–657.