Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maria Magdalena Barreca | + 2063 word(s) | 2063 | 2021-12-06 09:36:58 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | + 2 word(s) | 2065 | 2021-12-15 04:31:21 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Barreca, M.M. Molecular Mediators of RNA Loading into Extracellular Vesicles. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17130 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Barreca MM. Molecular Mediators of RNA Loading into Extracellular Vesicles. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17130. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Barreca, Maria Magdalena. "Molecular Mediators of RNA Loading into Extracellular Vesicles" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17130 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Barreca, M.M. (2021, December 15). Molecular Mediators of RNA Loading into Extracellular Vesicles. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/17130

Barreca, Maria Magdalena. "Molecular Mediators of RNA Loading into Extracellular Vesicles." Encyclopedia. Web. 15 December, 2021.

Copy Citation

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a family of membrane-coated vesicles with different proteomic and lipidomic profile, as well as different size. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated that non-coding RNA (ncRNAs) cooperate in the gene regulatory networks with other biomolecules, including coding RNAs, DNAs and proteins. Among them, microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and circular RNAs (circRNAs) are involved in transcriptional and translation regulation at different levels. Intriguingly, ncRNAs can be packed in vesicles, released in the extracellular space, and finally internalized by receiving cells, thus affecting gene expression also at distance.

exosomes

extracellular vesicles

non-coding RNA

miRNAs

lncRNAs

1. Introduction

1.1. Extracellular Vesicles (EVs)

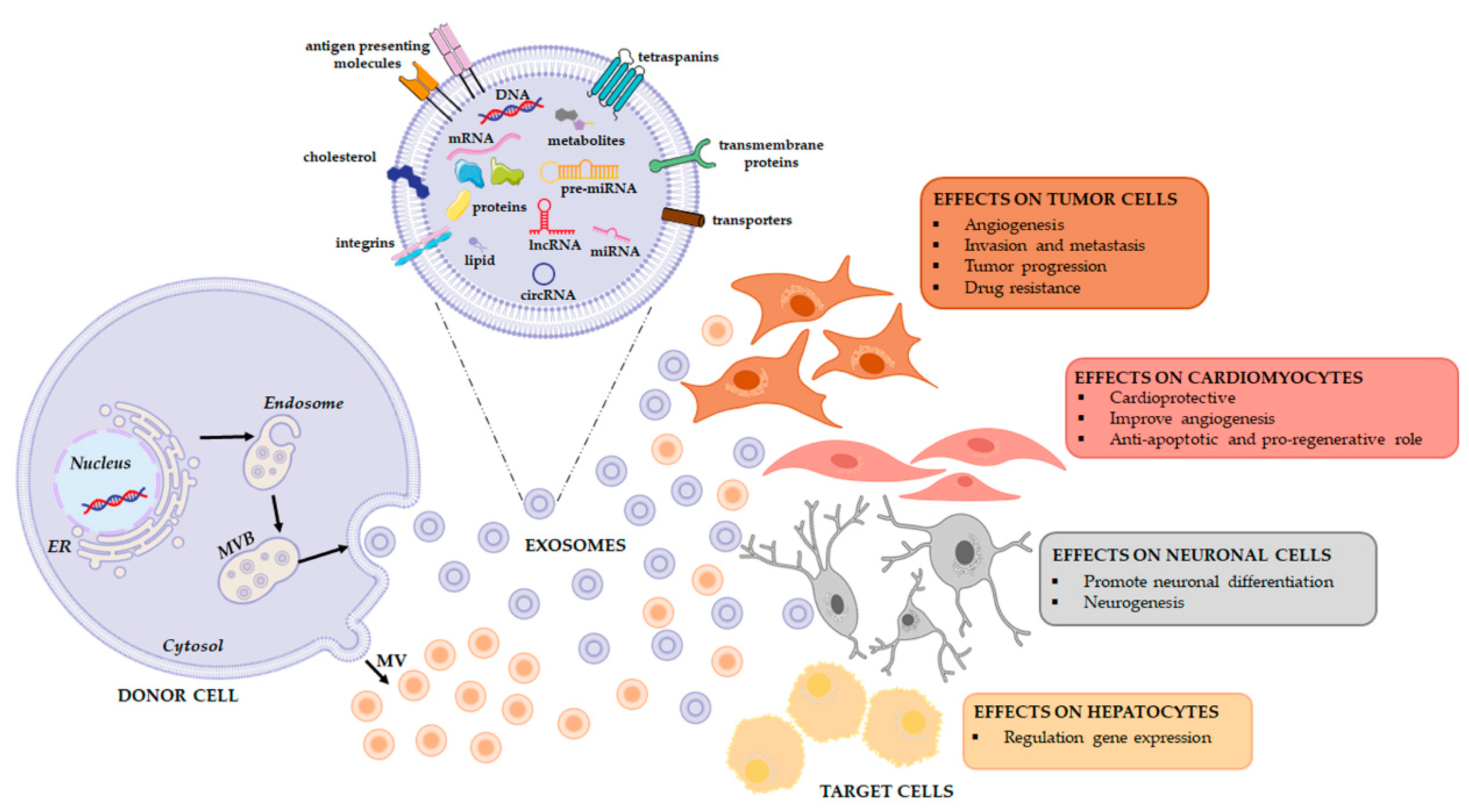

EVs are a family of membrane-coated vesicles with different proteomic and lipidomic profile, as well as different size. Nowadays the role of EVs is emerging as an important new area of biomedical research [1]. It is well known that EVs are actively secreted by cells and that their content can affect activities and functions of receiving cells, in physiological as well as in pathological conditions [2][3][4]. Due to their biogenesis, we can identify two different types of EVs: exosomes and microvesicles (MV) [5]. The last ones originate by direct budding of the plasma membrane with a rearrangement of the cytoskeleton [6]. On the contrary, the biogenesis and release of exosomes is a multi-step process. The different biogenesis of the EVs also affects the composition of the vesicles’ membrane. Finally, EVs are characterized by their size; generally, microvesicles range from 200 to 2000 nm while exosomes from 30 to 150/200 nm. Recently the ISEV society established that it is better to prefer other methods of classification because many vesicles are quite similar in size range [7][8]. Many studies have focused on the biological effects of EVs in cell-cell communication both between neighboring cells and between cells in distant body districts. Biological fluids carry the EVs released in the extracellular space until they find a landing place where dump their content through the fusion of plasma membranes or endocytosis [9]. Recently, a great number of data support the transport of ncRNAs among cells, demonstrating that they can exert special functional roles [10].

1.2. RNA Families in Extracellular Vesicles

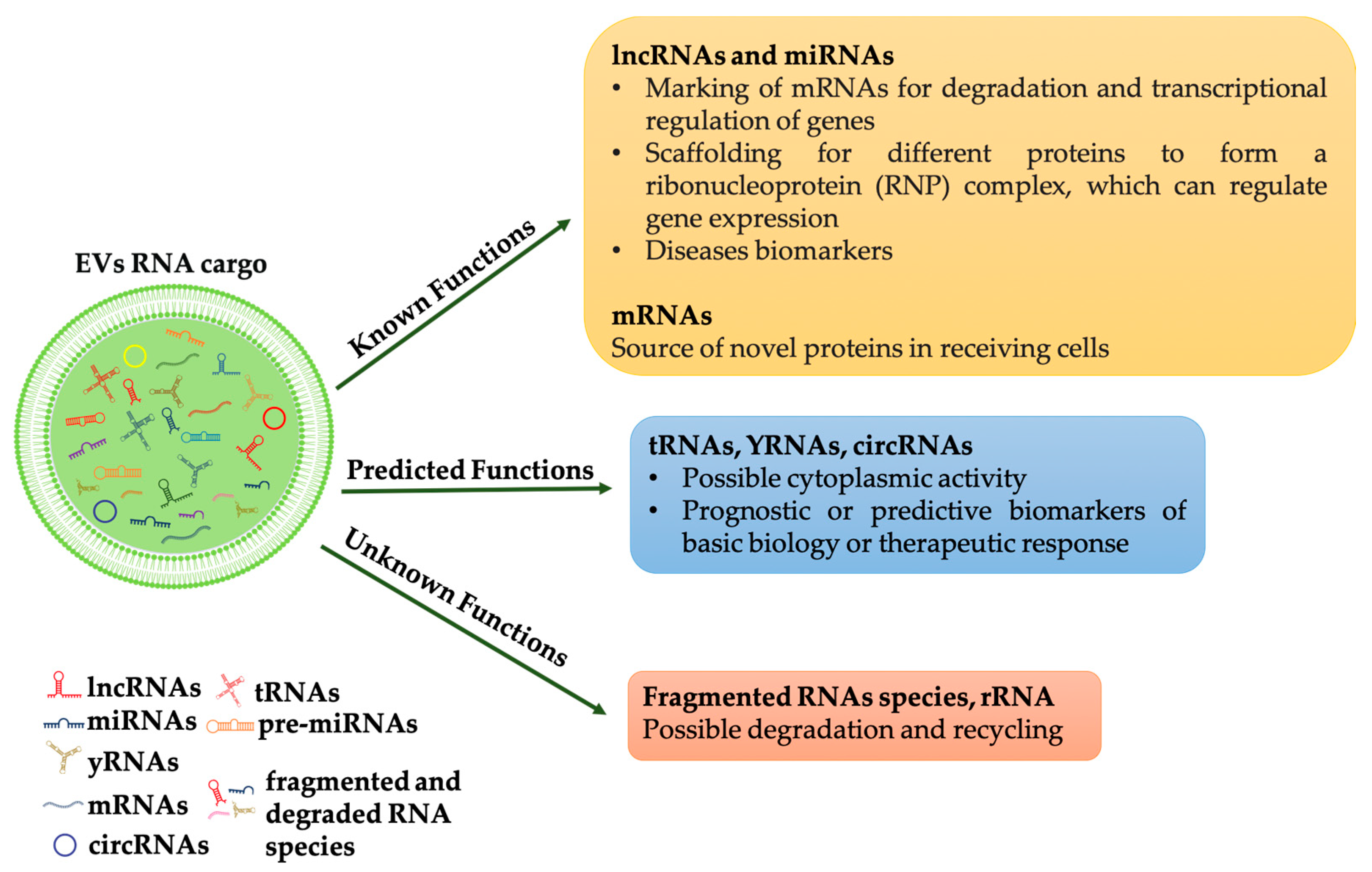

Much of the recent interest in EVs was triggered by the discovery of their involvement in horizontal transfer of secreted extracellular RNA (exRNA). From the first evidence of functional mRNA in EVs, a huge number of studies revealed a significant assortment of ncRNAs in EVs. The deep sequencing RNA technique allows demonstrating a selective enrichment of small ncRNAs in human-derived extracellular vesicles, isolated from different cytotypes [11][12]. Among them, small RNA families are the most abundant, these include small nuclear RNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, ribosomal RNAs, transfer RNAs, miRNAs. However, also larger RNAs groups, including mitochondrial RNAs, Y RNA, vault RNA, piwi RNA and long non-coding RNA have been found in EVs, for a detailed review of the different RNAs families in EV see [13]. A recent work of Mosbach et al. demonstrated that RNA sorting depends on its size but also on its origin, the authors in fact revealed that RNA polymerase III transcripts are preferentially associated with EVs [14]. As pointed out by [13] although several types of RNAs have been identified in EVs, only some of these have been demonstrated functioning in the recipient cell, i.e., miRNAs and lncRNAs. For other RNA molecules, such as tRNAs, can be assumed a possible activity in the cytoplasm of the recipient cells while the role of other RNA molecules such as mRNA fragments or ribosomal RNAs remains unclear (Figure 1).

Figure 1. RNAs species into EVs and their functions. RNAs in extracellular vesicles can be classified into three types: (1) RNAs that have known function when internalized into target cells, such as mRNAs, miRNAs and lncRNAs; (2) RNAs that are predicted to be functional (for example, tRNAs, YRNAs, circRNAs); (3) RNAs with unknown functions (for example, fragments RNAs and rRNAs), some of which may be functional, but others may be non-functional degradation products.

Still controversial is the presence of miRNA precursors: their identification, together with Dicer and Argonaute 2, let scientists to suppose that complete silencing machinery could be transferred by EVs [15][16]. However, the hypothesis was not largely confirmed by other investigators. Other conflicting observations in studying exRNAs are due to the different isolation strategies. For example, ultracentrifugation, the gold standard method for EVs purification, biases RNAs data. It in fact does not allow to separate vesicles from free ribonucleoproteins or lipoproteins both associated with RNAs [17]. To overcome this limitation, Lässer group developed a method combining size exclusion chromatography with a density cushion; this allows to isolate and characterize EVs from blood with minimal contamination by plasma proteins and lipoprotein particles [18].

Meanwhile, Jeppesen et al. used high-resolution density gradient fractionation to separate EVs from non-vesicular material, then, with a direct immunoaffinity capture (DIC) targeting classical exosomal tetraspanins, exosomes were specifically isolated from other types of EVs [19]. Nucleic acid analysis revealed that exRNAs are differentially expressed between EVs and non-vesicle compartments. Interestingly the authors demonstrated that miRNAs were mainly associated with extracellular non-vesicular fractions while the EVs were enriched in transfer RNA (tRNA) fragments. In addition, YRNA and vault RNA were particularly enriched in non-vesicular fractions [19].

2. The Effects of the Horizontal Transfer of EVs Derived RNAs

Many studies demonstrated the functional role of the RNA-cargo that, selectively packaged inside EVs, are transferred to target cells. Firstly, the transfer of exosomal mRNAs and miRNAs was reported by Valadi et al. in 2007, which revealed a “novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells” [20]. Since that study, numerous papers have demonstrated that the horizontal transfer of exosomes cargo can modulate target cells behaviors. Studies on tumor cells revealed as exosome-mediated RNA transfer may control tumor growth, affect its microenvironment, and promote metastases.

It is well known that a central event in tumor progression is the induction of angiogenesis. Focusing on this pathway it has been demonstrated that glioblastoma, chronic myelogenous leukemia, and breast cancer derived EVs can reprogram endothelial cells through horizontal transfer of their miRNAs cargo [21][22]. The involvement of cancer derived EVs in facilitating brain infiltration is worth mentioning. Lu and collaborators have recently demonstrated that exosomes derived by highly brain metastatic breast cancer cells are able to destroy the blood–brain barrier through its lncRNA GS1-600G8.5 [23][24]. Exosomal miRNAs have a role also in tumor drug resistance. Mao et al. support this hypothesis demonstrating that Adriamycin-resistant breast cancer cells deliver specific miRNAs through exosomes thus promoting drug resistance in neighboring cells [25]. Quin and collaborators demonstrated that exosomes derived from cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cell line A549 induce drug resistance in receiving cells. MiRNA profile identified the miR100-5p as the mediator of this process [26].

In addition, exosome-transported lncRNAs may participate in drug resistance induction. A recent paper by Wang et al. proved that the exosome-mediated transfer of lncRNA H19 induces doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer [27]. The authors showed that drug-resistant cells release exosomes enriched in lncH19; these exosomes increase the chemoresistance of doxorubicin once internalized by sensitive cells. Moreover, downregulation of H19 in sensitive cells ablated this effect thus confirming the direct role of the long non-coding RNA [27]. EVs released into the tumor microenvironment strongly affect metastatic niche. For example, the prometastatic miRNA miR-9 and miR-155, carried respectively by breast cancer derived exosomes and pancreatic cancer derived microvesicles, are able to reprogram fibroblast to cancer associated fibroblast (CAF) phenotype thus promoting tumor progression [28][29]. While the EV-mediated delivery of the miR-105 and miR-122 reprogram CAFs metabolism to sustain tumor growth [30][31]. Moreover, cancer derived EVs can reprogram immune cells thus preventing immunosurveillance and promoting immunotolerance in cancer microenvironment, as revised by Graner [32]. In addition, EVs derived RNAs profiling can be useful as a prognostic indicator to therapeutic response. For example, miR196a-5p and miR-501-3p were significantly downregulated in exosomes isolated from the urine of prostate cancer patients [33], while let7-b and miR-18a, isolated from plasma of multiple myeloma patients, were associated with overall survival [34]. As expected, the effects of the EV-transported RNA are not limited to the tumor context.

Barile and colleagues revealed the cardioprotective role of the different miRNAs transported by EVs derived from cardiac progenitor cells (CPC). They demonstrated that miR-210 inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis by targeting Ephrin A3 (cell surface GPI-bound ligand for Eph receptors) and PTP1b (protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1b). Moreover, EVs derived miR132 stimulates angiogenesis acting on RasGAP-p120, Ras GTPase activating protein p120 [35]. Furthermore, CPC derived exosomal miR21 exert similar effects preventing cell apoptosis by targeting PDCD4 (Programmed Cell Death 4) [36]. Similarly, Gray and collaborators, through microarray analysis of exosomes derived from hypoxic CPC, identified 11 miRNAs that improve cardiac function stimulating tube formation of endothelial cells and reducing fibrosis [37].

Regarding differentiation, it has been demonstrated that exosomes released from Neural stem/progenitor cells (NPCs) have an important role in neurogenesis; Ma and collaborators demonstrated that mouse cortical NPCs, isolated from fetal brain, promote neuronal differentiation through exosomal miR-21a [38].

Adipose tissue is an excellent resource for circulating exosomal miRNAs that have a role in regulating liver gene expression, as well as affecting obesity or diabetes. Adipose-derived exosomal miR-99b has been demonstrated to control in vivo fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) production [39]. While exosomes secreted by adipose tissue macrophages transfer miRNAs modulating, in vivo and in vitro, insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis [40].

All these experiments suggest that exosomes may be a vehicle of therapeutic non-coding RNAs in physiological and pathological conditions as well as in the field of regenerative therapy (Figure 2). To this end, a comprehensive analysis of the RNA loading mechanisms is appropriate.

Figure 2. Extracellular vesicles release and their functional effects on target cells. EVs are a heterogeneous population, both in form and content since their cargo is strictly dependent on the pathophysiological conditions of the cell at the exact moment in which it produces the vesicle. When studying the complexity of the EV-mediated cell-cell communication, it is necessary to evaluate that the same vesicle, i.e., the same message, can be interpreted differently depending on the cytotype that receives it. This will depend in good part on the gene expression profile of the recipient cell.

3. Loading of EVs and Cargo Sorting

3.1. RNA Binding Protein-Mediated Loading

Recent evidence highlighted the main role of RNA-binding proteins in RNA sorting and loading in EVs. Santangelo et al. have identified the RNA binding protein SYNCRIP (synaptotagmin-binding cytoplasmic RNA-interacting protein; also known as hnRNPQ or NSAP1) as a component of the hepatocyte exosomal miRNA sorting machinery. They showed that SYNCRIP knockdown impairs the internalization of miRNAs in exosomes [41]. Subsequently, Hobor et al., identified that SYNCRIP contains a sequence called NURR (N-terminal unit for RNA recognition) that recognizes and bind the motif GGCU/A in miRNAs. This interaction guides miRNA loading into exosomes [42].

In conclusion, several RNA binding proteins, alone or in combination with other molecular interactors may control RNA sorting inside EV (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Summary of proteins involved in the ncRNA packaging into EVs. RNA binding proteins alone or in cooperation with other proteins bind specific ncRNAs and selectively transport them into EVs. Membrane proteins are also involved in the ncRNA loading EVs mechanism.

3.2. Other Carriers for RNA Loading

It is well known that the ESCRT pathway is responsible for protein sorting into EVs [43][44]. Alix is an adaptor protein involved in EVs biogenesis and cargo sorting through an ESCRT dependent pathway [45]. However, new evidence indicated that Alix is involved in miRNAs loading into EVs. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed a direct interaction between Alix and the RNA binding protein Ago2, commonly involved in miRNA transport and processing. This complex drives Alix with Ago2-associated miRNAs into EVs [46][47]. A further connection between ESCRT complex and selective RNA loading was confirmed by Wozniak et al. [48]. In particular, the authors demonstrated that the RBP fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) interacts with the hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (Hrs), a component of the ESCRT complex. The RNA binding protein FMR1 acts as a chaperone that recognizes a specific sequence in miRNA (AAUGC) while Hrs allows complex internalization. Interestingly, inflammosome activation mediates this interaction, through the cleavage of the trafficking adaptor protein RILP (Rab-interacting lysosomal protein) that works as ride [48].

Cargo sorting could also be driven via ESCRT-independent pathways, e.g., through the neutral sphingomyelinase, phospholipase or other lipids and associated protein such as tetraspanin [49][50][51][52].

In conclusion, cargo sorting could be mediated by carriers commonly involved in EV biogenesis or in miRNA transport and processing. Cargo sorting could also be driven via ESCRT dependent or via ESCRT-independent pathways, e.g., through the neutral sphingomyelinase, phospholipase or other lipids and associated proteins (Figure 2).

References

- Boriachek, K.; Islam, M.N.; Moller, A.; Salomon, C.; Nguyen, N.T.; Hossain, M.S.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Shiddiky, M.J.A. Biological Functions and Current Advances in Isolation and Detection Strategies for Exosome Nanovesicles. Small 2018, 14, 1702153.

- Martellucci, S.; Orefice, N.S.; Angelucci, A.; Luce, A.; Caraglia, M.; Zappavigna, S. Extracellular Vesicles: New Endogenous Shuttles for miRNAs in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6486.

- Hafiane, A.; Daskalopoulou, S.S. Extracellular vesicles characteristics and emerging roles in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Metabolism 2018, 85, 213–222.

- Hosseinkhani, B.; Kuypers, S.; van den Akker, N.M.S.; Molin, D.G.M.; Michiels, L. Extracellular Vesicles Work as a Functional Inflammatory Mediator Between Vascular Endothelial Cells and Immune Cells. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1789.

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228.

- Li, B.; Antonyak, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Cerione, R.A. RhoA triggers a specific signaling pathway that generates transforming microvesicles in cancer cells. Oncogene 2012, 31, 4740–4749.

- Shao, H.; Im, H.; Castro, C.M.; Breakefield, X.; Weissleder, R.; Lee, H. New Technologies for Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1917–1950.

- Thery, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750.

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977.

- Xie, Y.; Dang, W.; Zhang, S.; Yue, W.; Yang, L.; Zhai, X.; Yan, Q.; Lu, J. The role of exosomal noncoding RNAs in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 37.

- Lunavat, T.R.; Cheng, L.; Kim, D.K.; Bhadury, J.; Jang, S.C.; Lasser, C.; Sharples, R.A.; Lopez, M.D.; Nilsson, J.; Gho, Y.S.; et al. Small RNA deep sequencing discriminates subsets of extracellular vesicles released by melanoma cells—Evidence of unique microRNA cargos. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 810–823.

- Huang, Q.; Yang, J.; Zheng, J.; Hsueh, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, L. Characterization of selective exosomal microRNA expression profile derived from laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma detected by next generation sequencing. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 40, 2584–2594.

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 585–606.

- Mosbach, M.-L.; Pfafenrot, C.; von Strandmann, E.P.; Bindereif, A.; Preußer, C. Molecular Determinants for RNA Release into Extracellular Vesicles. Cells 2021, 10, 2674.

- Clancy, J.W.; Zhang, Y.; Sheehan, C.; D’Souza-Schorey, C. An ARF6-Exportin-5 axis delivers pre-miRNA cargo to tumour microvesicles. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 856–866.

- Melo, S.A.; Sugimoto, H.; O’Connell, J.T.; Kato, N.; Villanueva, A.; Vidal, A.; Qiu, L.; Vitkin, E.; Perelman, L.T.; Melo, C.A.; et al. Cancer exosomes perform cell-independent microRNA biogenesis and promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 707–721.

- Van Deun, J.; Mestdagh, P.; Sormunen, R.; Cocquyt, V.; Vermaelen, K.; Vandesompele, J.; Bracke, M.; de Wever, O.; Hendrix, A. The impact of disparate isolation methods for extracellular vesicles on downstream RNA profiling. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 24858.

- Karimi, N.; Cvjetkovic, A.; Jang, S.C.; Crescitelli, R.; Hosseinpour Feizi, M.A.; Nieuwland, R.; Lotvall, J.; Lasser, C. Detailed analysis of the plasma extracellular vesicle proteome after separation from lipoproteins. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 2873–2886.

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445.

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659.

- Lucero, R.; Zappulli, V.; Sammarco, A.; Murillo, O.D.; Cheah, P.S.; Srinivasan, S.; Tai, E.; Ting, D.T.; Wei, Z.; Roth, M.E.; et al. Glioma-Derived miRNA-Containing Extracellular Vesicles Induce Angiogenesis by Reprogramming Brain Endothelial Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 2065–2074.

- Liu, Q.; Peng, F.; Chen, J. The Role of Exosomal MicroRNAs in the Tumor Microenvironment of Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3884.

- Lu, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, L.; Cao, Y. Exosomes Derived from Brain Metastatic Breast Cancer Cells Destroy the Blood-Brain Barrier by Carrying lncRNA GS1-600G8.5. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 7461727.

- Yi, Y.; Wu, M.; Zeng, H.; Hu, W.; Zhao, C.; Xiong, M.; Lv, W.; Deng, P.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, Y. Tumor-Derived Exosomal Non-Coding RNAs: The Emerging Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Applications in Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 738945.

- Mao, L.; Li, J.; Chen, W.X.; Cai, Y.Q.; Yu, D.D.; Zhong, S.L.; Zhao, J.H.; Zhou, J.W.; Tang, J.H. Exosomes decrease sensitivity of breast cancer cells to adriamycin by delivering microRNAs. Tumour Biol. 2016, 37, 5247–5256.

- Qin, X.; Yu, S.; Zhou, L.; Shi, M.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Shen, B.; Liu, S.; Yan, D.; Feng, J. Cisplatin-resistant lung cancer cell-derived exosomes increase cisplatin resistance of recipient cells in exosomal miR-100-5p-dependent manner. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 3721–3733.

- Wang, X.; Pei, X.; Guo, G.; Qian, X.; Dou, D.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, X.; Duan, X. Exosome-mediated transfer of long noncoding RNA H19 induces doxorubicin resistance in breast cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 6896–6904.

- Baroni, S.; Romero-Cordoba, S.; Plantamura, I.; Dugo, M.; D’Ippolito, E.; Cataldo, A.; Cosentino, G.; Angeloni, V.; Rossini, A.; Daidone, M.G.; et al. Exosome-mediated delivery of miR-9 induces cancer-associated fibroblast-like properties in human breast fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2312.

- Pang, W.; Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Feng, H.; Dai, X.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, X.; Yao, W. Pancreatic cancer-secreted miR-155 implicates in the conversion from normal fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Sci. 2015, 106, 1362–1369.

- Yan, W.; Wu, X.; Zhou, W.; Fong, M.Y.; Cao, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, C.H.; Fadare, O.; Pizzo, D.P.; et al. Cancer-cell-secreted exosomal miR-105 promotes tumour growth through the MYC-dependent metabolic reprogramming of stromal cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 597–609.

- Fong, M.Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, L.; Alontaga, A.Y.; Chandra, M.; Ashby, J.; Chow, A.; O’Connor, S.T.; Li, S.; Chin, A.R.; et al. Breast-cancer-secreted miR-122 reprograms glucose metabolism in premetastatic niche to promote metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 183–194.

- Graner, M.W.; Schnell, S.; Olin, M.R. Tumor-derived exosomes, microRNAs, and cancer immune suppression. Semin. Immunopathol. 2018, 40, 505–515.

- Rodriguez, M.; Bajo-Santos, C.; Hessvik, N.P.; Lorenz, S.; Fromm, B.; Berge, V.; Sandvig, K.; Line, A.; Llorente, A. Identification of non-invasive miRNAs biomarkers for prostate cancer by deep sequencing analysis of urinary exosomes. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 156.

- Manier, S.; Liu, C.J.; Avet-Loiseau, H.; Park, J.; Shi, J.; Campigotto, F.; Salem, K.Z.; Huynh, D.; Glavey, S.V.; Rivotto, B.; et al. Prognostic role of circulating exosomal miRNAs in multiple myeloma. Blood 2017, 129, 2429–2436.

- Barile, L.; Lionetti, V.; Cervio, E.; Matteucci, M.; Gherghiceanu, M.; Popescu, L.M.; Torre, T.; Siclari, F.; Moccetti, T.; Vassalli, G. Extracellular vesicles from human cardiac progenitor cells inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis and improve cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 103, 530–541.

- Xiao, J.; Pan, Y.; Li, X.H.; Yang, X.Y.; Feng, Y.L.; Tan, H.H.; Jiang, L.; Feng, J.; Yu, X.Y. Cardiac progenitor cell-derived exosomes prevent cardiomyocytes apoptosis through exosomal miR-21 by targeting PDCD4. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2277.

- Gray, W.D.; French, K.M.; Ghosh-Choudhary, S.; Maxwell, J.T.; Brown, M.E.; Platt, M.O.; Searles, C.D.; Davis, M.E. Identification of therapeutic covariant microRNA clusters in hypoxia-treated cardiac progenitor cell exosomes using systems biology. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 255–263.

- Ma, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, X.; Zheng, J.C. Exosomes released from neural progenitor cells and induced neural progenitor cells regulate neurogenesis through miR-21a. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 96.

- Thomou, T.; Mori, M.A.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; Konishi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Wolfrum, C.; Rao, T.N.; Winnay, J.N.; Garcia-Martin, R.; Grinspoon, S.K.; et al. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature 2017, 542, 450–455.

- Ying, W.; Riopel, M.; Bandyopadhyay, G.; Dong, Y.; Birmingham, A.; Seo, J.B.; Ofrecio, J.M.; Wollam, J.; Hernandez-Carretero, A.; Fu, W.; et al. Adipose Tissue Macrophage-Derived Exosomal miRNAs Can Modulate In Vivo and In Vitro Insulin Sensitivity. Cell 2017, 171, 372–384.

- Santangelo, L.; Giurato, G.; Cicchini, C.; Montaldo, C.; Mancone, C.; Tarallo, R.; Battistelli, C.; Alonzi, T.; Weisz, A.; Tripodi, M. The RNA-Binding Protein SYNCRIP Is a Component of the Hepatocyte Exosomal Machinery Controlling MicroRNA Sorting. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 799–808.

- Hobor, F.; Dallmann, A.; Ball, N.J.; Cicchini, C.; Battistelli, C.; Ogrodowicz, R.W.; Christodoulou, E.; Martin, S.R.; Castello, A.; Tripodi, M.; et al. A cryptic RNA-binding domain mediates Syncrip recognition and exosomal partitioning of miRNA targets. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 831.

- Katzmann, D.J.; Babst, M.; Emr, S.D. Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I. Cell 2001, 106, 145–155.

- Migliano, S.M.; Teis, D. ESCRT and Membrane Protein Ubiquitination. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biol. 2018, 57, 107–135.

- Larios, J.; Mercier, V.; Roux, A.; Gruenberg, J. ALIX- and ESCRT-III-dependent sorting of tetraspanins to exosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, 1–22.

- Iavello, A.; Frech, V.S.; Gai, C.; Deregibus, M.C.; Quesenberry, P.J.; Camussi, G. Role of Alix in miRNA packaging during extracellular vesicle biogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 958–966.

- Ye, Z.L.; Huang, Y.; Li, L.F.; Zhu, H.L.; Gao, H.X.; Liu, H.; Lv, S.Q.; Xu, Z.H.; Zheng, L.N.; Liu, T.; et al. Argonaute 2 promotes angiogenesis via the PTEN/VEGF signaling pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2015, 36, 1237–1245.

- Wozniak, A.L.; Adams, A.; King, K.E.; Dunn, W.; Christenson, L.K.; Hung, W.T.; Weinman, S.A. The RNA binding protein FMR1 controls selective exosomal miRNA cargo loading during inflammation. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201912074.

- Pegtel, D.M.; Gould, S.J. Exosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 487–514.

- Russell, A.E.; Sneider, A.; Witwer, K.W.; Bergese, P.; Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Cocks, A.; Cocucci, E.; Erdbrugger, U.; Falcon-Perez, J.M.; Freeman, D.W.; et al. Biological membranes in EV biogenesis, stability, uptake, and cargo transfer: An ISEV position paper arising from the ISEV membranes and EVs workshop. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1684862.

- Leidal, A.M.; Huang, H.H.; Marsh, T.; Solvik, T.; Zhang, D.; Ye, J.; Kai, F.; Goldsmith, J.; Liu, J.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; et al. The LC3-conjugation machinery specifies the loading of RNA-binding proteins into extracellular vesicles. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 187–199.

- Babst, M. MVB vesicle formation: ESCRT-dependent, ESCRT-independent and everything in between. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2011, 23, 452–457.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology; Cell Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

779

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Dec 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No