| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nicholas Bacci | + 1666 word(s) | 1666 | 2021-12-09 03:24:09 |

Video Upload Options

Forensic facial comparison is a human observer-based technique employed in forensic facial identification. Facial identification falls under the broader discipline of facial imaging, and involves the use of visual facial information to assist in person identification. Through the analysis of photographic or video evidence (e.g., CCTV), forensic facial identification is routinely utilized to associate persons of interest to criminal activity in a judicial context. The recommended approach to forensic facial comparison is facial examination by morphological analysis, whereby a facial feature list is used to analyze, compare, and evaluate visible facial features between a target image and a potential matching image. This process is then validated by a second analyst. Forensic facial comparison, and its broader discipline of facial identification, should not be confused with automated facial recognition technology or the innate psychological process of facial recognition.

1. Introduction

2. Terminology

3. Forensic Facial Comparison

4. Validation of Forensic Facial Comparison and Recommended Practice

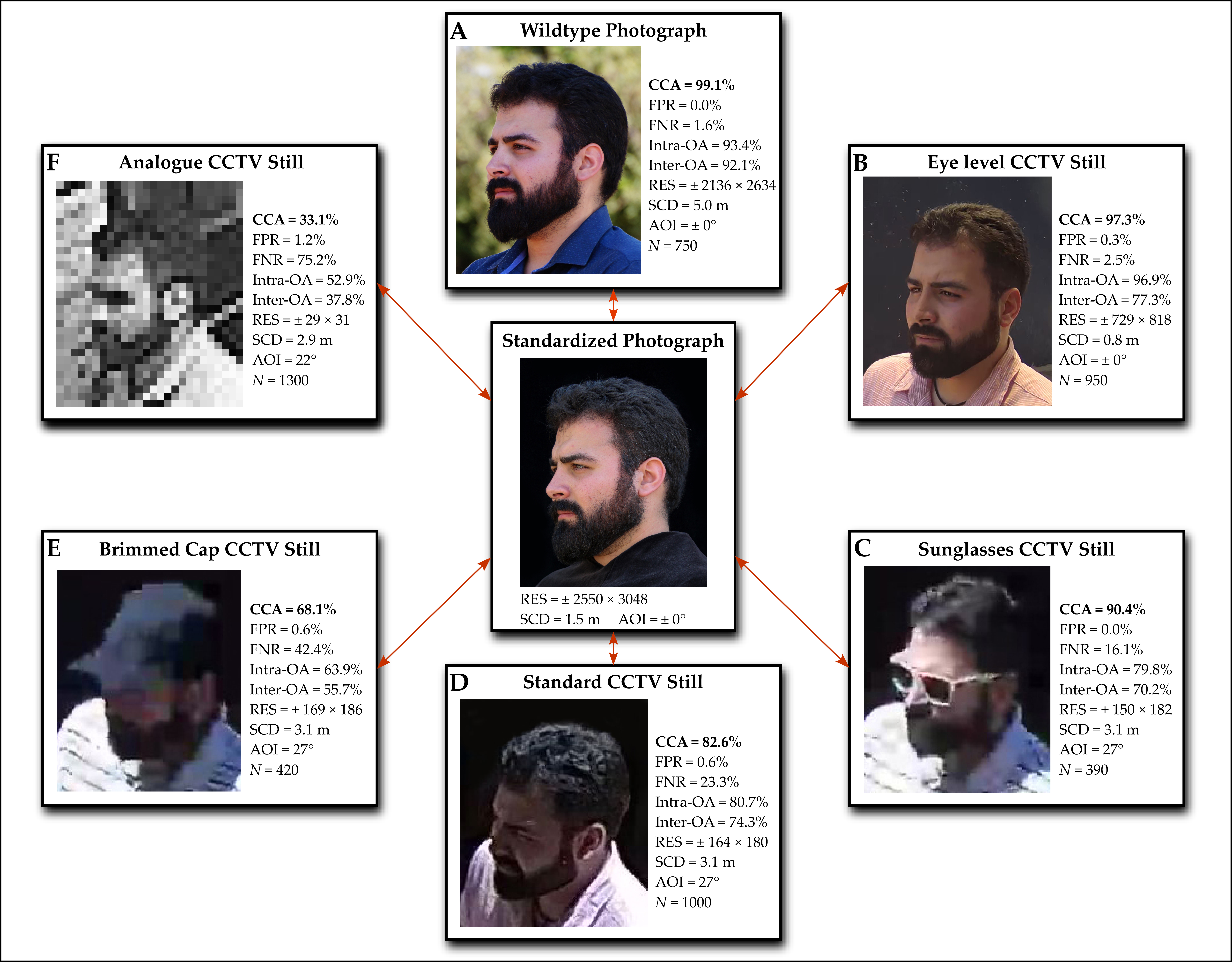

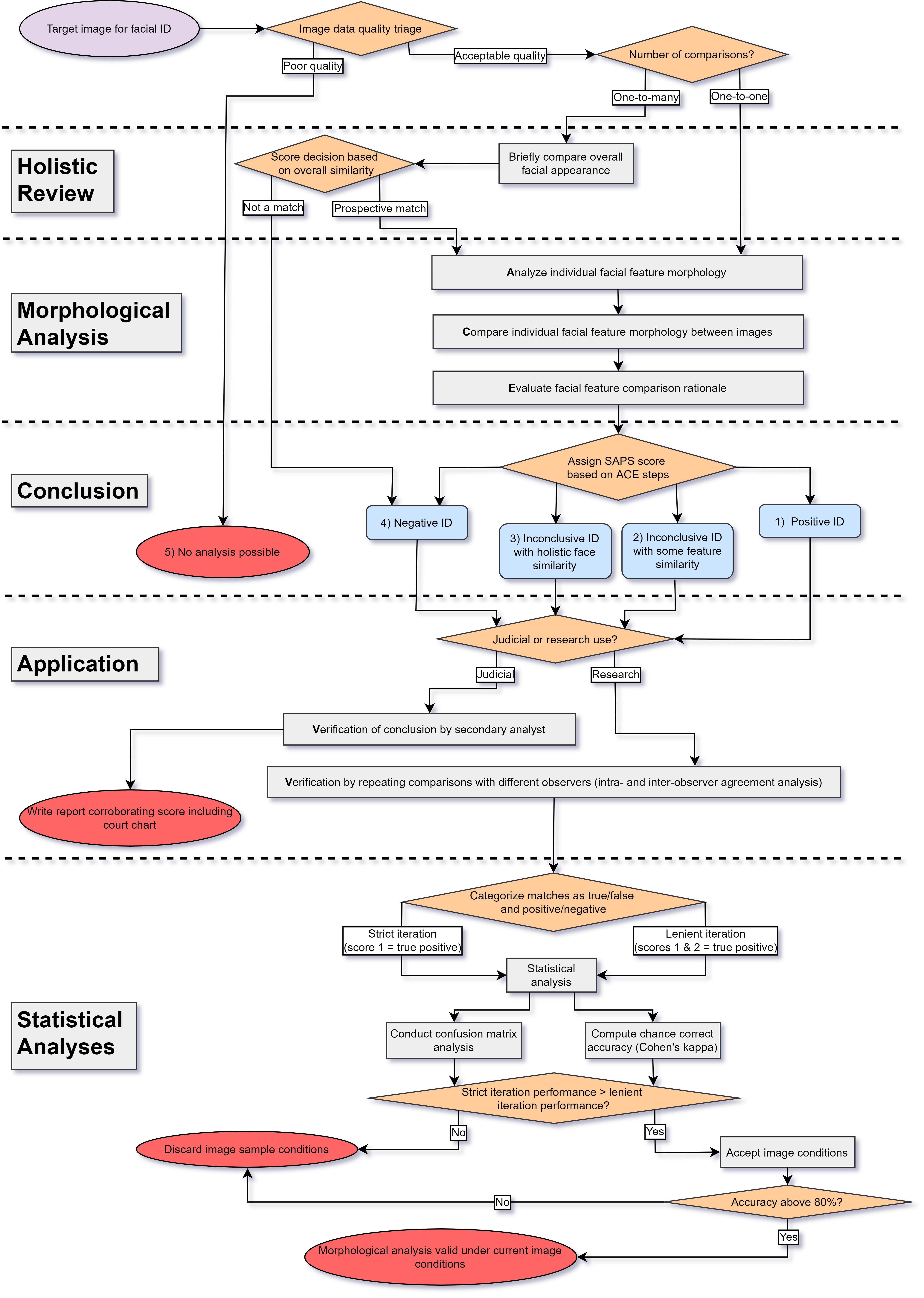

Figure 3. Flow diagram of the recommended morphological analysis process [39]. This approach to morphological analysis uses an ACE-V method in conjunction with the FISWG feature list [37], with the inclusion of the ENFSI’s image quality triaging [36] and the use of the South African Police Services (SAPS) scoring criteria [13] as adapted for research application [17]. Statistical analyses for research use are also recommended based on recent work [40] to allow for more detailed result interpretation and comparison among future studies.

5. Forensic Facial Comparison Limitations

The minimum criteria for facial examination across various CCTV installations, are not clearly highlighted, and a more thorough understanding of the limitations imposed on footage by specific installations is needed. While the global increase in CCTV data is beneficial to criminal investigation and facial comparison, there is a concerning lack of standardization of required installation, recording conditions, and image quality [35][42][43][44][45][46]. As a result, the usefulness of CCTV-derived facial images is difficult to assess and makes facial comparison challenging in contrast to controlled photographs and mugshots.

These limitations along the CCTV imaging chain are often acknowledged; however, few studies have assessed their implication in facial comparison accuracies [17][40][42][46][47][48]. Successful facial identification assessment is hindered by inconsistent recording conditions and poor image quality. Facial comparison accuracy and data quality are, thus, directly correlated [49][50], especially in terms of individual accuracy variation across multiple analysts [51] and individual analyst ability overestimation [52].

An overview of the general and more specific limiting factors of CCTV data in the application of MA and their specific effects in the process of facial comparison is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of CCTV systems’ technical limitations in the application of morphological analysis.

|

General Limitations |

Specific Limitations |

Effects |

|

Camera placement |

Camera height above ground [17][40][41][53][54] |

Image composition affected—target size and screen/picture height [17][40][41][53] |

|

Camera specifications |

Analogue or digital [42] Sensor size [53] Lens focal length [53] |

Reduced image quality [17][40][53] Image distortion and artefacts [53] |

|

Lighting conditions |

|

Loss of facial detail [40][41] Shadows and overexposure form artificial boundaries and altered facial appearance [41][62] Optical distortions [53] |

|

Image quality |

Noise/grain [53] Video compression [44] Color [40] |

|

|

Data loss and corruption |

Network infrastructure [38] Software [53] Imminent weather [38] Power outages [38] Compression rate [44] |

Inconsistent network connection and coverage—transfer corruption [38] Partial or complete data loss [38] |

References

- Jäger, J. Photography: A means of surveillance? Judicial photography, 1850 to 1900. Crime Hist. Sociétés 2001, 5, 27–51.

- Bertillon, A.; McClaughry, R.W. Signaletic Instructions Including the Theory and Practice of Anthropometrical Identification; McClaughry, R.W., Ed.; The Werner Company: Chicago, IL, USA, 1896.

- Mokwena, R.J. The Value of Photography in the Investigation of Crime Scenes; University of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012.

- Bell, A. Crime scene photography in England, 1895–1960. J. Br. Stud. 2018, 57, 53–78.

- Lindegaard, M.R.; Bernasco, W. Lessons Learned from Crime Caught on Camera. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2018, 55, 155–186.

- Norris, C.; McCahill, M.; Wood, D. The Growth of CCTV: A global perspective on the international diffusion of video surveillance in publicly accessible space. Surveill. Soc. 2002, 2, 110–135.

- Piza, E.L.; Welsh, B.C.; Farrington, D.P.; Thomas, A.L. CCTV surveillance for crime prevention: A 40-year systematic review with meta-analysis. Criminol. Public Policy 2019, 18, 135–159.

- Jain, A.K.; Klare, B.; Park, U. Face Matching and Retrieval in Forensics Applications. IEEE Multimed. 2012, 19, 20.

- Moyo, S. Evaluating the Use of CCTV Surveillance Systems for Crime Cotnrol and Prevention: Selected Case Studies from Johannesburg and Tshwane, Gauteng; University of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019.

- Goold, B.; Loader, I.; Thumala, A. The banality of security: The curious case of surveillance cameras. Br. J. Criminol. 2013, 53, 977–996.

- Duncan, J. How CCTV surveillance poses a threat to privacy in South Africa. Conversation 2018, 1–3. Available online: https://theconversation.com/how-cctv-surveillance-poses-a-threat-to-privacy-in-south-africa-97418 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Kleinberg, K.F.; Siebert, J.P. A study of quantitative comparisons of photographs and video images based on landmark derived feature vectors. Forensic Sci. Int. 2012, 219, 248–258.

- Steyn, M.; Pretorius, M.; Briers, N.; Bacci, N.; Johnson, A.; Houlton, T.M.R. Forensic facial comparison in South Africa: State of the science. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 287, 190–194.

- Jackson, A. The Admissibility of Identification Evidence Made on the Basis of Recognition from Photographs Taken at a Crime Scene. J. Crim. Law 2016, 80, 234–236.

- Houlton, T.M.R.; Steyn, M. Finding Makhubu: A morphological forensic facial comparison. Forensic Sci. Int. 2018, 285, 13–20.

- Steyn M.; Pretorius M.; Briers N.; Bacci N.; Johnson A.; Houlton T.M.R.; Forensic facial comparison in South Africa: State of the science. Forensic Science International 2018, 287, 190-194, 10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.04.006.

- Bacci N.; Houlton T.M.R.; Briers N.; Steyn M.; Validation of forensic facial comparison by morphological analysis in photographic and CCTV samples. International Journal of Legal Medicine 2021, 135, 1965-1981, 10.1007/s00414-021-02512-3.

- Schüler, G.; Obertová, Z. Visual identification of persons: Facial image comparison and morphological comparative analysis. In Statistics and Probability in Forensic Anthropology; Obertová, Z., Stewart, A., Cattaneo, C., Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 313–330.

- Behrman, B.W.; Davey, S.L. Eyewitness identification in actual criminal cases: An archival analysis. Law Hum. Behav. 2001, 25, 475–491.

- Boyce, M.A.; Lindsay, D.S.; Brimacombe, C.A.E. Investigating investigators: Examining the impact of eyewitness identification evidence on student-investigators. Law Hum. Behav. 2008, 32, 439–453.

- Davis, J.P.; Valentine, T.; Wilkinson, C. Facial image comparison. In Craniofacial Identification; Wilkinson, C., Rynn, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 136–153. ISBN 9781139049566.

- Valentine, T.; Davis, J.P. Forensic Facial Identification: Theory and Practice of Identification from Eyewitnesses, Composites and CCTV; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781118469538.

- Facial Identification Scientific Working Group. Facial Comparison Overview and Methodology Guidelines. 2019. Available online: https://fiswg.org/fiswg_facial_comparison_overview_and_methodology_guidelines_V1.0_20191025.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Adjabi, I.; Ouahabi, A.; Benzaoui, A.; Taleb-Ahmed, A. Past, present, and future of face recognition: A review. Electronics 2020, 9, 1188.

- Akhtar, Z.; Rattani, A. A Face in any Form: New Challenges and Opportunities for Face Recognition Technology. Computer 2017, 50, 80–90.

- Lai, X.; Patrick Rau, P.L. Has facial recognition technology been misused? A user perception model of facial recognition scenarios. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106894.

- Grother, P.; Ngan, M.; Hanaoka, K. Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT) Part 2: Identification; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards & Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019.

- Dodd, V. UK Police Use of Facial Recognition Technology a Failure, Says Report. The Guardian, 15 May 2018.

- Grother, P.; Ngan, M.; Hanaoka, K. Face Recognition Vendor Test Part 3: Demographic Effects; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards & Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, December 2019.

- Spaun, N.A. Facial comparisons by subject matter experts: Their role in biometrics and their training. Int. Conf. Biom. 2009, 5558, 161–168.

- White, D.; Dunn, J.D.; Schmid, A.C.; Kemp, R.I. Error Rates in Users of Automatic Face Recognition Software. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139827.

- Wilkinson, C.; Evans, R. Are facial image analysis experts any better than the general public at identifying individuals from CCTV images? Sci. Justice 2009, 49, 191–196.

- Valentine, T.; Davis, J.P. Forensic Facial Identification; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781118469118.

- Speckeis, C. Can ACE-V be validated? J. Forensic Identif. 2011, 61, 201–209.

- Stephan, C.N.; Caple, J.M.; Guyomarc’h, P.; Claes, P. An overview of the latest developments in facial imaging. Forensic Sci. Res. 2019, 4, 10–28.

- ENFSI. Best Practice Manual for Facial Image Comparison; ENFSI: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; Volume 1, Available online: https: //enfsi.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/ENFSI-BPM-DI-01.pdf

- Facial Identification Scientific Working Group. Facial Image Comparison Feature List for Morphological Analysis. 2018. Available online: https://fiswg.org/FISWG_Morph_Analysis_Feature_List_v2.0_20180911.pdf

- Bacci, N.; Davimes, J.; Steyn, M.; Briers, N. Development of the Wits Face Database: An African database of high-resolution facial photographs and multimodal closed-circuit television (CCTV) recordings. F1000Research 2021, 10, 131.

- Bacci, N.; Davimes, J.G.; Steyn, M.; Briers, N. Forensic Facial Comparison: Current Status, Limitations, and Future Directions. Biology 2021, 10, 1269. https:// doi.org/10.3390/biology10121269

- Bacci, N.; Steyn, M.; Briers, N. Performance of forensic facial comparison by morphological analysis across optimal and suboptimal CCTV settings. Sci. Justice 2021, 61, 743–754.

- Bacci, N.; Briers, N.; Steyn, M. Assessing the effect of facial disguises on forensic facial comparison by morphological analysis. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 1220–1233.

- Lee, W.-L.; Wilkinson, C.; Memon, A.; Houston, K. Matching unfamiliar faces from poor quality closed-circuit television (CCTV) footage: An evaluation of the effect of training on facial identification ability. Axis Online J. CAHId 2009, 1, 19–28.

- Kleinberg, K.F.; Vanezis, P.; Burton, A.M. Failure of anthropometry as a facial identification technique using high-quality photographs. J. Forensic Sci. 2007, 52, 779–783.

- Keval, H.U.; Sasse, M.A. Can we ID from CCTV? Image quality in digital CCTV and face identification performance. Mob. Multimedia Image Process. Secur. Appl. 2008, 6982, 69820.

- Smith, R.A.; MacLennan-Brown, K.; Tighe, J.F.; Cohen, N.; Triantaphillidou, S.; MacDonald, L.W. Colour analysis and verification of CCTV images under different lighting conditions. Image Qual. Syst. Perform. V 2008, 6808, 68080.

- Bindemann, M.; Attard, J.; Leach, A.; Johnston, R.A. The effect of image pixelation on unfamiliar-face matching. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2013, 27, 707–717.

- Burton, A.M.; Wilson, S.; Cowan, M.; Bruce, V. Face recognition in poor-quality video: Evidence from security surveillance. Psychol. Sci. 1999, 10, 243–248.

- Ritchie, K.L.; White, D.; Kramer, R.S.S.; Noyes, E.; Jenkins, R.; Burton, A.M. Enhancing CCTV: Averages improve face identification from poor-quality images. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2018, 32, 671–680.

- Fysh, M.C.; Bindemann, M. The Kent Face Matching Test. Br. J. Psychol. 2018, 109, 219–231.

- Kramer, R.S.S.; Mohamed, S.; Hardy, S.C. Unfamiliar Face Matching With Driving Licence and Passport Photographs. Perception 2019, 48, 175–184.

- Burton, A.M.; White, D.; McNeill, A. The Glasgow Face Matching Test. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 286–291.

- Bindemann, M.; Attard, J.; Johnston, R.A. Perceived ability and actual recognition accuracy for unfamiliar and famous faces. Cogent Psychol. 2014, 1, 986903.

- Damjanovski, V. CCTV from Light to Pixels, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2014; ISBN 9780124045576.

- Ward, D. Testing Camera Height vs. Image Quality; Pennsylvania, USA. 2013. Available online: https://ipvm.com/reports/ testing-camera-height

- Stephan, C.N. Perspective distortion in craniofacial superimposition: Logarithmic decay curves mapped mathematically and by practical experiment. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015, 257, 520.e1–520.e8.

- Stephan, C.N.; Armstrong, B. Scientific estimation of the subject-to-camera distance from facial photographs for craniofacial superimposition. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2021, 4, 100238.

- Stephan, C.N. Estimating the Skull-to-Camera Distance from Facial Photographs for Craniofacial Superimposition. J. Forensic Sci. 2017, 62, 850–860.

- Smith, S. CCTV Market Outlook 2017. Cision PR Newswire, 15 May 2014.

- Wood, L. CCTV Cameras—Worldwide Market Outlook Report 2018–2026: Dome Cameras Dominate. Businesswire 2018. Available online: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180913005519/en/CCTV-Cameras---Worldwide-Market-Outlook- Report-2018-2026-Dome-Cameras-Dominate---ResearchAndMarkets.com

- Surette, R. The thinking eye: Pros and cons of second generation CCTV surveillance systems. Policing 2005, 28, 152–173.

- Kruegle, H. CCTV Surveillance: Analog and Digital Video Practices and Technology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780750677684.

- Cohen, N.; Gattuso, J.; MacLennan-Brown, K. CCTV Operational Requirements Manual; Cohen, N., Gattuso, J., MacLennan-Brown, K., Eds.; Home Office Scientific Development Branch: Sandridge, UK, 2009; ISBN 9781847269027.

- Viték, S.; Klíma, M.; Krasula, L. Video compression technique impact on efficiency of person identification in CCTV systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings—International Carnahan Conference on Security Technology, Rome, Italy, 13–16 October 2014.

- Qi, X.; Liu, C. Mitigate compression artifacts for face in video recognition. In Proceedings of the Disruptive Technologies in Information Sciences IV, online. 27 April–8 May 2020; Blowers, M., Hall, R.D., Dasari, V.R., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; p. 25.

- Blunden, B. Anti-Forensics: The Rootkit Connection. In Proceedings of the Black Hat USA 2009, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 25–30 July 2009; pp. 1–44.

- D’Orazio, C.; Ariffin, A.; Choo, K.-K.R. IOS Anti-Forensics: How CanWe Securely Conceal, Delete and Insert Data? In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 13 October 2013; pp. 6–9. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2339819

- Kissel, R.; Regenscheid, A.; Scholl, M.; Stine, K. Guidelines for Media Sanitization; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014; Volume 800.

- Ariffin, A.; Choo, K.K.; Yunos, Z. Forensic readiness: A case study on digital CCTV systems antiforensics. In Contemporary Digital Forensic Investigations ofCloud and Mobile Applications; Choo, K.-K.R., Dehghantanha, A., Eds.; Syngress: London, UK, 2017; pp. 147–162.