Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Renata Finelli | + 1531 word(s) | 1531 | 2021-11-23 05:12:49 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1531 | 2021-12-01 09:56:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Finelli, R. Steroidogenesis, Oxidative Stress and Male Hypogonadism. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16609 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Finelli R. Steroidogenesis, Oxidative Stress and Male Hypogonadism. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16609. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Finelli, Renata. "Steroidogenesis, Oxidative Stress and Male Hypogonadism" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16609 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Finelli, R. (2021, December 01). Steroidogenesis, Oxidative Stress and Male Hypogonadism. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/16609

Finelli, Renata. "Steroidogenesis, Oxidative Stress and Male Hypogonadism." Encyclopedia. Web. 01 December, 2021.

Copy Citation

Steroid sex hormones are classified as androgens, estrogens, and progestogens. Although all three classes are important in male and female physiology, androgens are associated with "musculisation" effects and are considered primarily male sex hormones. Androgens have diverse functions in muscle physiology, lean body mass, the regulation of adipose tissue, bone density, neurocognitive regulation, and spermatogenesis, male reproductive and sexual function.

male hypogonadism

1. Introduction

Steroid sex hormones are classified as androgens, estrogens, and progestogens. Although all three classes are important in male and female physiology, androgens are associated with "musculisation" effects and are considered primarily male sex hormones [1]. Androgens have diverse functions in muscle physiology, lean body mass, the regulation of adipose tissue, bone density, neurocognitive regulation, and spermatogenesis, male reproductive and sexual function [2].

When testosterone synthesis is impaired, a condition of hypogonadism arises that affects quality of life and wellbeing [3]. Because of the importance of testosterone in male physiology, hypogonadism further leads to increased fat accumulation, a reduction in lean body mass, and osteoporosis. Hypogonadism may also arise as a consequence of the ageing process, which can be described as the gradual deterioration in biological function over time, reducing quality of life and increasing the risk of degenerative noncommunicable chronic diseases (NCDs) [4]. In fact, ageing has an important relationship as both a risk factor and/or a comorbidity with NCDs, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, type-2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), and numerous malignancies [2][4].

All these conditions have in common an imbalance in the redox homeostasis in favor of higher levels of oxidants, leading to the development of oxidative stress [5]. Oxidative stress is a leading mechanism that drives the ageing process, with a complex relationship in the pathogenesis of age-related NCDs. Moreover, it may have an important role in age-related hypogonadism associated with the increased risk of NCDs [6][7][8].

2. Steroidogenesis and Male Hypogonadism

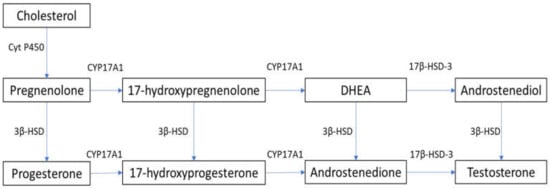

In males, testosterone is synthesized primarily in Leydig cells through LH receptor (LHR) binding, with the activation of G-coupled protein and adenylyl cyclase, which increases intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). This leads to the activation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein that mediates the mitochondrial uptake of cholesterol, which is converted to pregnenolone by the cytochrome P450 side chain cleavage enzyme [9][10]. In humans, 17α-hydroxylase (CYP17A1) converts pregnenolone to 17α-hydroxy-pregnenolone and androgen dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). DHEA is converted to androstenedione via 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), and then to testosterone via 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-3 (17β-HSD-3) [9][10]. The steroidogenesis pathway is summarized in Figure 1. cAMP activation is required for the expression of steroidogenesis enzymes [11]. Androgens exist both in free form and bound to serum proteins. Although approximately 98% of testosterone is bound to albumin or sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), about 2% of circulating testosterone is not bound to serum proteins and is able to penetrate into cells and exert its metabolic effects [12].

Figure 1. Steroidogenesis pathway. 3β-HSD: 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; 17β-HSD-3: 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-3; Cyt P450: cytochrome P450; CYP17A1: 17α-hydroxylase; DHEA: dehydroepiandrosterone.

Male hypogonadism is a clinical syndrome caused by a disruption of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis that affects the testicular synthesis of testosterone [3]. Various terminologies are used to describe this syndrome, including testicular failure, androgen deficiency syndrome, testosterone deficiency syndrome, andropause, androgen deficiency in ageing males (ADAM), and late-onset hypogonadism (LOH) [3]. Hypogonadism is estimated to affect up to 12% of male adults in the general population, and the incidence is expected to increase in the future [3], mainly because of the rise in the population aged 65 years and over.

The classification of hypogonadism is based on testicular or non-testicular causes. Testicular failure is classified as primary (hypergonadotropic) hypogonadism, and the causes include Klinefelter syndrome, Sertoli-cell-only syndrome, cryptorchidism, testicular trauma, mumps orchitis, radiation or chemotherapy treatment, and autoimmune diseases [3]. Pituitary or hypothalamic causes are classified as secondary (hypogonadotropic) hypogonadism, and include Kalman’s syndrome, pituitary adenoma, hyperprolactinaemia, and medications [3]. Although often reported as secondary hypogonadism, the nontesticular causes of "mixed" hypogonadism can be caused by ageing, excessive alcohol consumption, and corticosteroid treatment [3]. Important clinical associations with hypogonadism as risk factors and/or comorbidities include obesity, metabolic syndrome, T2DM, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis [3]. Furthermore, lower levels of testosterone in healthy men are a predictor of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and related comorbidities [13]. Hypogonadism is also associated with environmental exposures that induce oxidative stress, which can result in male infertility. This includes exposure to air pollution, pesticides, heavy metals, radiation, and, particularly, endocrine-disrupting chemicals [14].

Hypogonadism presents clinically with sexual dysfunction, prominently including erectile dysfunction, infertility, increased adiposity with decreased muscle mass, reduced bone density, and osteoporosis, fatigue, and depression [3]. Diagnosis is confirmed with a reduced serum total testosterone on two separate occasions [15], while the determination of the serum LH differentiates primary (increased LH: hypergonadotropic) from secondary (reduced LH: hypogonadotropic) hypogonadism [15]. Age-associated hypogonadism may be characterized by normal or low-normal levels of LH [15].

3. Oxidative Stress and Hypogonadism

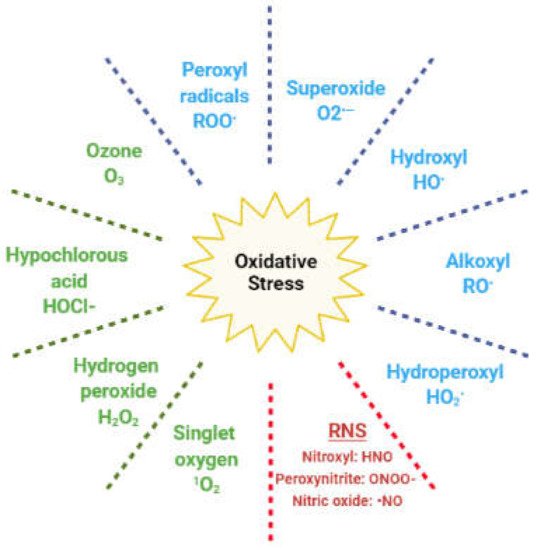

In living cells, redox (reduction and oxidation) reactions mediate numerous physiological pathways; hence, the intracellular levels of oxidants and antioxidants play an important role in this fine regulation [5][16]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are oxygen-based oxidants that are generated during cellular metabolism, predominantly in the mitochondria. They act as physiological mediators in several processes, such as immune regulation, inflammation, apoptosis, and the regulation of genetic expression, among others [5][16]. The ROS family includes both radical and nonradical species (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Reactive species responsible for oxidative stress. In blue: radical oxygen species; in green: nonradical oxygen species; in red: reactive nitrogen species (RNS).

The former are molecules with unpaired electrons in the outer orbit; hence, they easily react with any other cellular molecule, including lipids, proteins, and DNA. Nonradical species include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which can react with ferrous ions in the Fenton reaction and lead to the generation of hydroxyl radical. Other oxidants originate from nitrogen and are classified as reactive nitrogen species (RNS) [5]. Redox homeostasis is maintained by enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidant compounds, which are endogenously generated, or introduced exogenously through the diet (Table 1) [17].

Table 1. Enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants.

| Enzymatic | Nonenzymatic |

|---|---|

| Superoxide dismutase (SOD) | Vitamin C, vitamin E, vitamin B9 |

| Catalase (CAT) | Selenium, Zinc, Mn2+ |

| Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) | Carotenoids, flavonoids, lycopene |

| Glutathione reductase (GR) | Taurine, hypotaurine |

| Glutathione-S-transferase (GST) | Glutathione, inositol, cysteine, coenzyme Q10 |

| Thioredoxin |

When the fine redox equilibrium is shifted in favour of oxidants through increased ROS or reduced antioxidants, a condition of oxidative stress arises. As numerous cellular signaling pathways respond to variations in redox status, oxidative stress can consequently result in the disruption of the cellular signalling and cause cellular damage [18]. Several studies have described the ROS-dependent regulation of molecular pathways, such as extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)/Akt, p38, p53, protein-kinase C, phospholipase C, nuclear factor kB (NF kB), and JAK/STAT. These can have either a pro- or anti-apoptotic effect (for review on the topic, see [19][20]. In clinical practice, oxidative stress has been widely described as a contributing factor in several pathological conditions, such as cardiovascular, autoimmune, and neurodegenerative disorders, as well as cancer, diabetes, and infertility [21][22][23][24][25].

ROS are physiologically produced during the enzymatic reactions of steroidogenesis. Monooxygenase reactions require electron donation from NADPH through adrenodoxin reductase and adrenodoxin [26][27]. Here, electron leakage results in the generation of superoxide and other ROS [26][28]. Experiments in a mouse Leydig tumor (MA-10) cell line demonstrated that ROS mediate the cAMP-activation of RAS and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, after the binding of the LH hormone on Leydig cell receptors [29]. The activation of these pathways is reported to positively modulate the proliferation and survival of Leydig cells, as well as steroidogenesis [30][31].

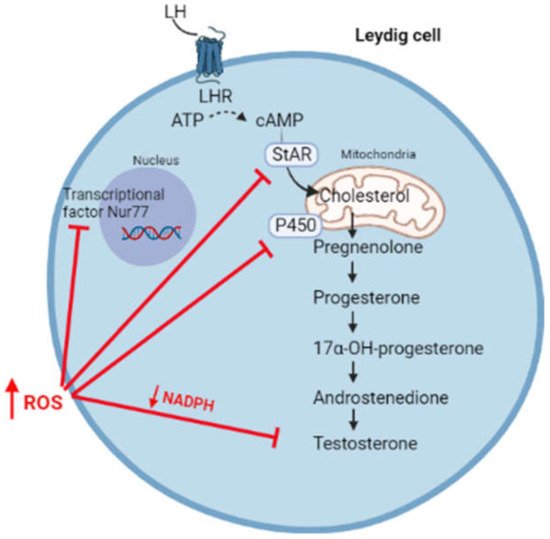

However, a switch of the redox status towards oxidative stress can affect steroidogenesis, resulting in the reduced synthesis of androgens (Figure 3).

Figure 3. High levels of ROS affect steroidogenesis through the inhibition of transcriptional factor Nur77, the synthesis of StAR, enzymatic P450 activity, and by reducing the levels of NADPH cofactor.

High levels of ROS hyperactivates the JNK signalling, which suppresses the activity of Nur77, a transcriptional factor regulating the expression of several steroidogenic enzymes [32]. Moreover, free radicals can oxidize the heme catalytic group of cytochrome P450, resulting in enzymatic inactivation [33][34]. By using oxidative agents, Chen et al. reported an increased phosphorylation of the MAPK family members (ERK1/2, JNK, and p38) associated with reduced testosterone production in MA-10 cells, highlighting the importance of the redox status in the regulation of steroidogenesis [35]. In this regard, it has been suggested that the activation of the p38 pathway is responsible for reduced testosterone production, possibly through the activation of cyclo-oxygenase2 (COX2) [35][36][37]. In fact, the overexpression of COX-2 has been associated with the reduced expression of StAR and, consequently, with reduced testosterone synthesis [38][39]. Moreover, high levels of ROS are responsible for the depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane, associated with the post-transcriptional inhibition of the StAR protein [40].

ROS scavenging relies on antioxidant systems. The reduced synthesis of testosterone was observed in Nrf2 knock-out mice, where Nrf2 is a transcription factor regulating the expression of antioxidant systems in response to oxidative stress [41]. Experiments conducted in young and aged rats showed that the depletion of glutathione (GSH) was accompanied by reduced testosterone synthesis [42]. In addition, the switch towards an oxidative status with reduced levels of NADPH can indirectly affect steroidogenesis through the inhibition of enzymatic activities. In fact, NADPH is an important cofactor of several endogenous antioxidants, such as GSH and thioredoxin, as well as enzymes involved in steroidogenesis [10][43].

References

- Pillerová, M.; Borbélyová, V.; Hodosy, J.; Riljak, V.; Renczés, E.; Frick, K.M.; Tóthová, Ľ. On the role of sex steroids in biological functions by classical and non-classical pathways. An update. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 62, 100926.

- Traish, A.M. Negative impact of testosterone deficiency and 5α-reductase inhibitors therapy on metabolic and sexual function in men. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1043, 473–526.

- Dandona, P.; Rosenberg, M.T. A practical guide to male hypogonadism in the primary care setting. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 682–696.

- Araujo, A.B.; Wittert, G.A. Endocrinology of the aging male. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 25, 303–319.

- Morrell, C.N. Reactive oxygen species: Finding the right balance. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 571–572.

- Smetana, K.; Lacina, L.; Szabo, P.; Dvoánková, B.; Broẑ, P.; Ŝedo, A. Ageing as an important risk factor for cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016, 36, 5009–5017.

- Luo, J.; Mills, K.; le Cessie, S.; Noordam, R.; van Heemst, D. Ageing, age-related diseases and oxidative stress: What to do next? Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 57, 100982.

- Höhn, A.; Weber, D.; Jung, T.; Ott, C.; Hugo, M.; Kochlik, B.; Kehm, R.; König, J.; Grune, T.; Castro, J.P. Happily (n)ever after: Aging in the context of oxidative stress, proteostasis loss and cellular senescence. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 482–501.

- Dohle, G.R.; Smit, M.; Weber, R.F.A. Androgens and male fertility. World J. Urol. 2003, 21, 341–345.

- Miller, W.L.; Auchus, R.J. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr. Rev. 2011, 32, 81–151.

- Payne, A.H.; Youngblood, G.L.; Sha, L.; Burgos-Trinidad, M.; Hammond, S.H. Hormonal regulation of steroidogenic enzyme gene expression in Leydig cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1992, 43, 895–906.

- Czub, M.P.; Venkataramany, B.S.; Majorek, K.A.; Handing, K.B.; Porebski, P.J.; Beeram, S.R.; Suh, K.; Woolfork, A.G.; Hage, D.S.; Shabalin, I.G.; et al. Testosterone meets albumin-the molecular mechanism of sex hormone transport by serum albumins. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 1607–1618.

- Pivonello, R.; Menafra, D.; Riccio, E.; Garifalos, F.; Mazzella, M.; De Angelis, C.; Colao, A.A. Metabolic disorders and male hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 345.

- Roychoudhury, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Choudhury, A.P.; Das, A.; Jha, N.K.; Slama, P.; Nath, M.; Massanyi, P.; Ruokolainen, J.; Kesari, K.K. Environmental factors-induced oxidative stress: Hormonal and molecular pathway disruptions in hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 837.

- Darby, E.; Anawalt, B.D. Male hypogonadism: An update on diagnosis and treatment. Treat. Endocrinol. 2005, 4, 293–309.

- Baskaran, S.; Finelli, R.; Agarwal, A. Reactive oxygen species in male reproduction: A boon or a bane? Andrologia 2020, 53, e13577.

- Rahal, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Yadav, B.; Tiwari, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Dhama, K. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: The interplay. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 761264.

- Dröge, W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 47–95.

- Martindale, J.L.; Holbrook, N.J. Cellular response to oxidative stress: Signaling for suicide and survival. J. Cell. Physiol. 2002, 192, 1–15.

- Ray, P.; Huang, B.; Tsuji, Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 981–990.

- Beatty, S.; Koh, H.H.; Phil, M.; Henson, D.; Boulton, M. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2000, 45, 115–134.

- Maritim, A.C.; Sanders, R.A.; Watkins, J.B. Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: A review. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2003, 17, 24–38.

- Kattoor, A.J.; Pothineni, N.V.K.; Palagiri, D.; Mehta, J.L. Oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2017, 19, 42.

- Uttara, B.; Singh, A.; Zamboni, P.; Mahajan, R. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: A review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2009, 7, 65–74.

- Agarwal, A.; Parekh, N.; Panner Selvam, M.K.; Henkel, R.; Shah, R.; Homa, S.T.; Ramasamy, R.; Ko, E.; Tremellen, K.; Esteves, S.; et al. Male oxidative stress infertility (MOSI): Proposed terminology and clinical practice guidelines for management of idiopathic male infertility. World J. Men’s Health 2019, 37, 296.

- Hanukoglu, I. Antioxidant protective mechanisms against reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by mitochondrial P450 systems in steroidogenic cells. Drug Metab. Rev. 2006, 38, 171–196.

- Ziegler, G.A.; Vonrhein, C.; Hanukoglu, I.; Schulz, G.E. The structure of adrenodoxin reductase of mitochondrial P450 systems: Electron transfer for steroid biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 289, 981–990.

- Quinn, P.G.; Payne, A.H. Steroid product-induced, oxygen-mediated damage of microsomal cytochrome P-450 enzymes in Leydig cell cultures. Relationship to desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 2092–2099.

- Tai, P.; Ascoli, M. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a critical role in the cAMP-induced activation of RAS and the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in leydig cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2011, 25, 885–893.

- Tai, P.; Shiraishi, K.; Ascoli, M. Activation of the lutropin/choriogonadotropin receptor inhibits apoptosis of immature Leydig cells in primary culture. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 3766–3773.

- Martinelle, N.; Holst, M.; Söder, O.; Svechnikov, K. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases are involved in the acute activation of steroidogenesis in immature rat leydig cells by human chorionic gonadotropin. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 4629–4634.

- Lee, S.Y.; Gong, E.Y.; Hong, C.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Han, J.S.; Ryu, J.C.; Chae, H.Z.; Yun, C.H.; Lee, K. ROS inhibit the expression of testicular steroidogenic enzyme genes via the suppression of Nur77 transactivation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 1591–1600.

- Lin, H.L.; Myshkin, E.; Waskell, L.; Hollenberg, P.F. Peroxynitrite inactivation of human cytochrome P450s 2B6 and 2E1: Heme modification and site-specific nitrotyrosine formation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 1612–1622.

- Karuzina, I.I.; Archakov, A.I. The oxidative inactivation of cytochrome P450 in monooxygenase reactions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1994, 16, 73–97.

- Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Lin, C.; Beattie, M.; Liu, J.; Zirkin, B. Effect of glutathione redox state on Leydig cell susceptibility to acute oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 323, 147–154.

- Abidi, P.; Zhang, H.; Zaidi, S.M.; Shen, W.J.; Leers-Sucheta, S.; Cortez, Y.; Han, J.; Azhar, S. Oxidative stress-induced inhibition of adrenal steroidogenesis requires participation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 198, 193–207.

- Zaidi, S.K.; Shen, W.J.; Bittner, S.; Bittner, A.; McLean, M.P.; Han, J.; Davis, R.J.; Kraemer, F.B.; Azhar, S. p38 MAPK regulates steroidogenesis through transcriptional repression of StAR gene. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 53, 1–16.

- Wang, X.; Dyson, M.T.; Jo, Y.; Stocco, D.M. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 activity enhances steroidogenesis and steroidogenic acute regulatory gene expression in MA-10 mouse Leydig cells. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 3368–3375.

- Wang, X.J.; Shen, C.L.; Dyson, M.T.; Eimerl, S.; Orly, J.; Hutson, J.C.; Stocco, D.M. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulation of the age-related decline in testosterone biosynthesis. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 4202–4208.

- Diemer, T.; Allen, J.A.; Hales, H.K.; Hales, D.B. Reactive oxygen disrupts mitochondria in MA-10 tumor leydig cells and inhibits steroidogenic acute regulatory (STAR) protein and steroidogenesis. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 2882–2891.

- Chen, H.; Jin, S.; Guo, J.; Kombairaju, P.; Biswal, S.; Zirkin, B.R. Knockout of the transcription factor Nrf2: Effects on testosterone production by aging mouse Leydig cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 409, 113–120.

- Chen, H.; Pechenino, A.S.; Liu, J.; Beattie, M.C.; Brown, T.R.; Zirkin, B.R. Effect of glutathione depletion on Leydig cell steroidogenesis in young and old Brown Norway rats. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 2612–2619.

- Fernandez-Marcos, P.J.; Nóbrega-Pereira, S. NADPH: New oxygen for the ROS theory of aging. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 50814–50815.

More

Information

Subjects:

Endocrinology & Metabolism

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No